It’s become clear in recent months that the odds of getting vaccinated against COVID-19 vary dramatically based on where a person lives. But an analysis of 191 countries and territories shows just how unequal the global distribution of COVID-19 vaccines has been — and how tied to a country’s wealth. While rich countries like the United States, Britain, Israel, and the members of the European Union are vaccinating large percentages of their populations, most of the world’s countries are still at or close to zero percent.

Unavoidable constraints on vaccine manufacturing capacity are made worse by vaccine hoarding among rich governments, their pre-purchasing of future supplies at rates poorer countries cannot afford, and their reluctance to share technical know-how with the developing world or allow other countries to copy the recipes for vaccines owned by powerful corporations headquartered in the U.S. and Europe. Oxfam estimates that just 43 percent of global COVID-19 vaccine production capacity is currently being used to produce any one of the several vaccines that are known to be safe and effective.

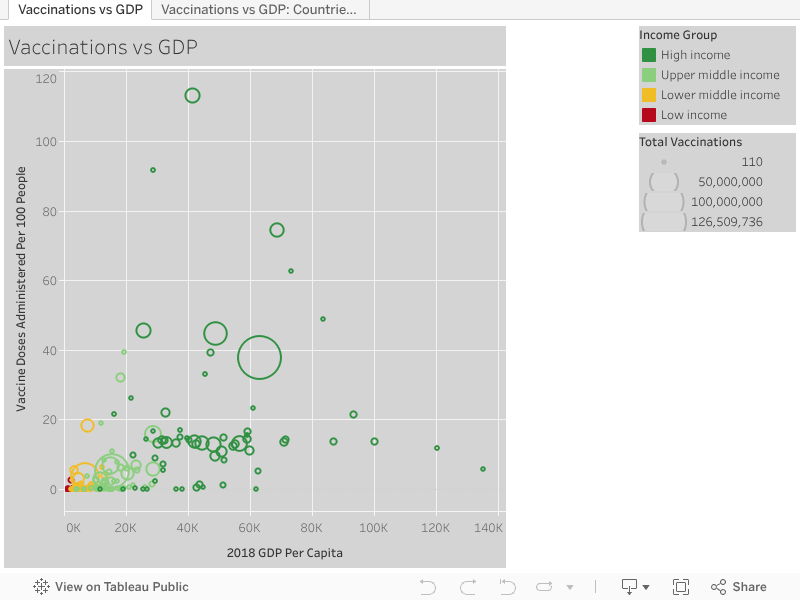

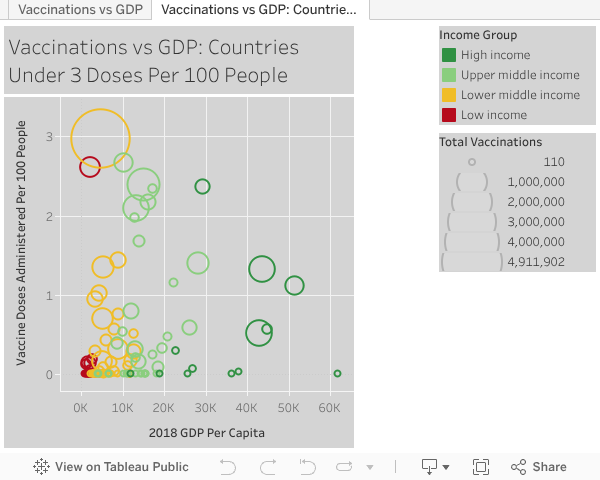

An analysis by Type Investigations found that countries classified by the World Bank as “high income” have collectively administered 21.1 doses per 100 residents, while countries classified as “low income” have administered just 0.1 doses per 100 residents. Even “upper middle income” countries, home to 2.9 billion people, were far behind “high income” countries with just 4.7 doses per 100 people, which is itself more than double the rate in “lower middle income” countries, home to another 3 billion people. Of 191 countries and territories analyzed, 116 of them (61%) have administered fewer than 3 doses per 100 people. Though 59% of the countries below 3 doses per 100 people are considered “low” or “lower middle” in income, some rich countries also fall into this category like Australia, Japan, and South Korea, where governments were faster to contain outbreaks but slower to order vaccines.

These findings build on earlier research that found a positive association between GDP per capita and vaccination rates. A coalition of mostly low- and middle-income countries led by South Africa and India have been asking since last year for a temporary suspension of the patent protections that make it illegal for their domestic producers to copy or modify vaccine recipes without the license of the multinational corporations that produced those vaccines using, in part, billions in public, taxpayer money. On March 10, these governments were rebuffed yet again at the WTO by a coalition of rich countries led by the U.S., U.K., and European Union.

The U.S. government has various incentives for allowing poor countries to vaccinate their populations as quickly and cheaply as possible: For one thing, uncontrolled community transmission in poor countries provides a fertile ground for viral mutations that could eventually find their way around the existing vaccines’ protection. Meanwhile, the government’s geopolitical rivals are making their own vaccines available to many poorer countries freely or cheaply. But those incentives seem to pale in comparison to protecting profit for a handful of corporations.

U.S. President Joe Biden has responded to increasing questioning from American media by promising that the U.S. will be sharing vaccines globally once it has vaccinated its own population. Millions of doses of the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine, stockpiled by the U.S. but unusable since the FDA has not authorized the vaccine, have started to be shared with Canada and Mexico, where the vaccine is authorized, with an expectation of future repayment.

Talking to the Washington Post in late February, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Biden’s chief medical advisor on the coronavirus, expressed support for rethinking the U.S. government’s approach to global vaccine access but fell short of rocking the corporate boat. “You can make arrangements with companies that would allow them both to maintain a considerable amount of profit,” he said, “at the same time that areas of the world that don’t have resources can share in a way that would be lifesaving to literally millions of people.”