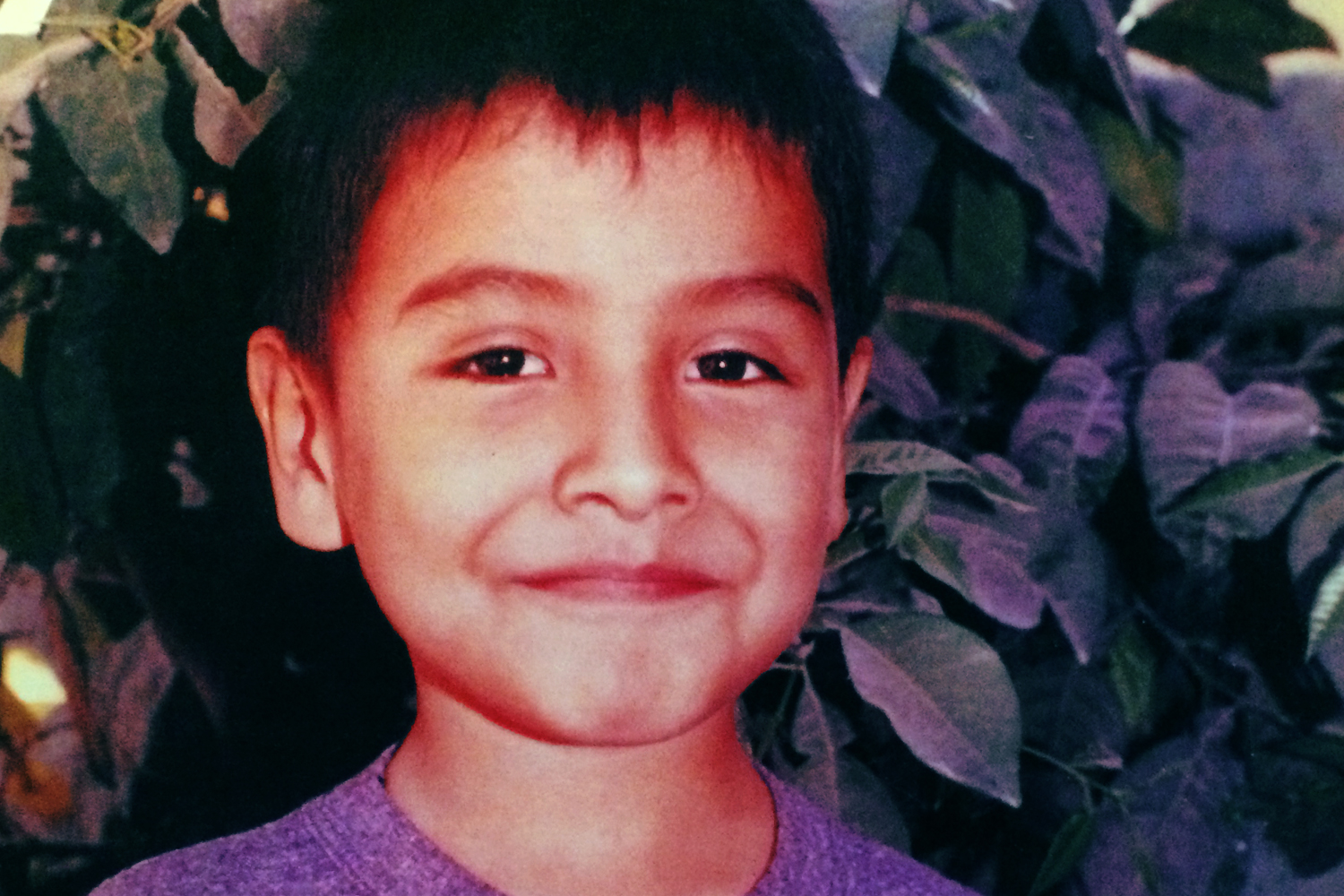

It was a warm sunny afternoon in 2008 in the dusty suburb of La Azucena. Eight-year-old Miguel Ángel Lopez Rocha was kicking a ball with his friends. A group of boys were playing near the Ahogado Canal, a tributary to the Santiago River and a recipient of factory discharge, that cuts through one of the most prosperous industrial zones in Mexico, located in El Salto, Jalisco.

Someone kicked the ball into the canal. It was Lopez Rocha’s turn to retrieve it. As he reached down to pick it up, he tripped and fell directly into the backwaters of the canal.

Later that night, feeling dizzy, Lopez Rocha stumbled into the bathroom. He was vomiting profusely. His mother rushed him to a hospital in nearby Guadalajara, where doctors quickly determined that the young boy was suffering from arsenic poisoning. Hours later, Lopez Rocha fell into a coma.

He died 18 days later. Doctors attributed the boy’s death to arsenic poisoning. His family and local environmentalists are convinced it was his fall into the canal that killed him. Tests done in the canal months later found elevated levels of arsenic and other heavy metals, but it is impossible to know the levels at the time or just how dangerous the canal was when the boy fell in. One government agency, the National Commission for Human Rights also believed the cause of death was arsenic poisoning from the canal. It filed a complaint against the National Water Commission, the agency responsible for enforcing environmental regulation. The complaint alleged a cluster of similar cases in the area — people sick with respiratory diseases and dying of cancer — all traceable to the polluted Santiago River. The Human Rights Commission demanded the area be declared an emergency zone. But in 2009 the former Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources, Juan Rafael Elvira Quesada, refused, saying such an action would mean “the paralysis of a very important amount of investment in the region.”

Miguel Angel Lopez Rocha

Fusion Investigates has found that, six years later, the Mexican government has done little to improve the condition of the Santiago River. Our investigation reveals a broken environmental regulatory system reliant on companies self-reporting chemical discharges. Meanwhile one government study found 80 percent of companies examined discharge waste into the river in violation of environmental laws, including US-based companies. Still, Fusion Investigates found the National Water Commission has not been able to identify a single time when any company in the El Salto area has been fined for releasing excessive amounts of toxic waste into the river in the past decade.

The Santiago River surges over a giant cliff along the edge of downtown El Salto. The falls were once known as the Niagara of Mexico. But what was once a popular tourist destination, replete with fish, otters, and other wildlife, has now become a location to avoid. At times, the river gives off a piercing sulphuric smell that wafts up into the town. Some El Salto veterans insist one should spend no more than 15 minutes along the Santiago waterfalls.

The El Salto waterfall, the epicenter of the pollution of the Santiago River.Image: Mauricio Palos/Boreal Collective/Fusion

It’s not easy to escape the “river of death,” as locals call it. On some days, during the rainy season, phosphorus creates a foamy substance that creeps up the banks of the river and into the yards of families who live nearby. On those days, some parents gather their children and take them indoors. This foam is known to burn the skin and eat the paint off of cars. Disease is ever-present in this region. “Before there were incidences of kidney failure and cancer every once in a while,” Rodolfo Ramirez Chávez, a local doctor, told Fusion Investigates, comparing the level of illness today with 30 years ago. “Here on the other side of the street a woman died of kidney failure and her son as well…Around the corner there is another child with kidney failure. Further up a little boy died of kidney failure. You can now count them by the block,” he said. Documents obtained by Fusion Investigates from Mexico’s health department reveal that kidney failure is the fifth leading cause of death in El Salto. Across the rest of the state of Jalisco, kidney disease is much less prevalent — ranking 10th on the list of causes of death. Many residents of the town also have a permanent cough. In the past 8 years, documents show a total of 157,863 cases of respiratory illness in El Salto. The town’s population is 138,000.

There is a water treatment plant in the region which opened in 2012. It’s meant to address the pollution of the Santiago River. It is around three miles upstream from El Salto and serves Guadalajara’s metropolitan area. Then Mexican president Felipe Calderón said at its opening ceremony, “We want the rivers that have been converted into drains to return to being clean.” But even though it’s one of the biggest treatment plants in Mexico, it doesn’t treat heavy metals and many synthetic chemicals — which local doctors believe is one of the main causes of illness.

There are about 300 companies along the Santiago River. Many of them are US household names: multinational businesses like, Pepsi, Nestlé, and Hershey’s; chemical factories like Sanmina, Quimikao, and Huntsman, a supplier of dyes to a popular American jeans maker; and Celanese, which makes cigarette filters.

Information about the real state of Mexican waterways does exist, but it’s difficult to get hold of. After a lengthy legal battle with Greenpeace, the Jalisco State Water Commission released a damning study, with data from 2009 and 2010 showing the contaminated state of the river.

It found that factories are the main reason why more than 1,000 chemicals course through the Santiago River. Along with arsenic, factories dump large amounts of chrome, lead, zinc, mercury, toluene, phosphorus, and cyanide, as well as synthetic chemicals into the river.

Fusion Investigates has identified at least 26 US-based companies operating in the area. At least 12 of them have discharged toxic waste into the river or its tributaries, according to publicly available information, Fusion Investigates has found. According to the government report, five of those US-based companies have discharged chemical waste in excess of the law.

The same practices in the United States have led to fines in the past. In Mexico, though, enforcement of environmental regulation is lax at best.

The system designed to measure the waste is riddled with possible conflicts of interest. Companies in Mexico contract private laboratories to analyze chemical discharge, and the companies then send a set of data to the National Water Commission. But often these laboratories are also contracted by the companies for other jobs simultaneously. Cindy McCulligh, a PhD candidate at Guadalajara’s Center for Advanced Studies in Social Anthropology, has studied the polluting of the river for the last decade. She says the regulatory system is flawed. “If I do an analysis of your discharge and you’re not in compliance, I am going to let you know before this goes off to the [National Water Commission],” she said.

Some of the reports obtained by Fusion Investigates, raise questions about their accuracy. One example is Sanmina, a Fortune 500 company. In its reporting — the numbers for several categories looks curiously similar — in many cases, it appears the only difference is where the decimal point is placed.

“It’s obviously a very rough calculation that I don’t think is based on any water quality analysis,” McCulligh said of the figures. Sanmina did not respond to questions regarding the surprising similarity of the numbers or their environmental practices.

The State Water Commission’s own research declared portions of the river a health hazard. Residents near some parts of the river and its tributaries are exposed to levels of heavy metals far in excess of the maximum environmental standard, including in the town where Lopez Rocha lived. The report concluded the contamination needed to be reversed “in the short term” because “the adverse consequences are already evident.” The waste produced by major factories clocked in well above Mexico’s federal limit on chemical discharge, according to the report.

Raúl Güitron Robles is president of the Industrial Association of El Salto (AISAC), the Mexican equivalent of a chamber of commerce. As head of the association, he said companies are concerned about the health of the El Salto community. But he has two jobs; Robles is also president of Quimikao, a company that has polluted the Santiago River. According to the State Water Commission report, Quimikao discharged grease and oils at a level 46 times above the legal limit. In the same report, tests showed the company dumped 52 times above the legal limit for suspended solids (indicators of water quality) and 13 times above the limit for nitrogen. When asked about exceeding the limits, Robles said he couldn’t speak on behalf of the company, but he told Fusion Investigates it’s the government’s job to regulate. “The authorities should be the ones determining that, because they are the ones that set the parameters. They determine what sanctions are needed,” he said.

Robles didn’t refute the report’s findings. “We haven’t doubted their results and studies,” he told Fusion Investigates. But he was quick to defend the company’s more recent practices. “Quimikao is in compliance today, with the requirements set by the authority. Otherwise they would have taken action already,” he said.

Or maybe not.

Mexican authorities appear to have done little to enforce environmental regulations. Documents obtained by Fusion Investigates show that over the past 10 years in the El Salto region, the National Water Commission couldn’t identify one instance in which any company was fined for dumping or discharging toxic waste into the Santiago River. Fusion was able to identify only one fine that was actually applied by the Water Commission in the past decade — for failure to have a permit.

McCulligh, the researcher who studies the river, told Fusion Investigates the government isn’t willing to enforce Mexico’s environmental standards. “What becomes clear to me is a type of corruption that is not simply the lack of ethical and professional behavior on the part of individuals,” she said, “but generalized lack of willingness to enforce standards for industrial wastewater discharge.”

A broken sewer line oozes waste near the Ahogado Canal in Lopez Rocha’s former neighborhood.Image: Mauricio Palos/Boreal Collective/Fusion

In 2011, a former top bureaucrat from the National Water Commission, César Coll Carabias, told local environmental organizations, “People dump what they want, in the amounts they like, in the conditions they prefer.” But that hasn’t translated into government action. Fusion Investigates sought a response from the National Water Commission regarding its enforcement practices, but officials declined, saying the information could interfere with upcoming elections. “As soon as elections are over, we will gladly set up an interview with you,” the government organization told Fusion Investigates.

Twenty to 30 years ago, a number of the companies in El Salto had plants in the United States. But as environmental regulation grew stronger, doing business became more expensive. The incentive to move to Mexico, and other developing countries, grew stronger as companies were increasingly held accountable for their dumping practices on American soil. But in recent decades there has been another incentive as well: The 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) dramatically reduced export tariffs for foreign companies, and that opened the floodgates for US companies seeking to take advantage of Mexico’s relatively cheap labor and lax environmental regulation. Driving through the El Salto region, one sees many factories with names of companies one used to see in industrial areas of the United States.

In the past 20 years, El Salto’s industrial zone has brought a steady increase of investment, helping make the Guadalajara Metropolitan zone the third largest economic engine in Mexico. Robles, from the local Industrial Association, said El Salto currently has 51,500 direct industry jobs, and he anticipates that a new $475 million investment will bring an additional 2,000 jobs this year. While industrial growth continues, cleaning up the Santiago River would take decades.

The State Water Commission’s study estimates that cleaning up the Santiago River would take at least 20 years at an estimated $643 million. But few resources have been allocated to the river, as municipalities pass the responsibility on to the state government. The states insist the Federal government is in charge of maintaining national rivers. The Federal government, meanwhile, insists lower level authorities are not enforcing their own laws. Meanwhile, companies continue production unabated.

Fusion Investigates contacted several companies that were identified in the Water Commission Report as having discharged potentially toxic waste in excess of limits established by Mexican law. Of the four US-based companies we contacted, Celanese and Huntsman responded to questions. Hershey’s and Pepsi chose not to respond. Switzerland-based Nestle S.A., also responded to questions.

According to the State Water Commission study that examined pollution in 2009 and 2010, Celanese discharged five times over the limit of phosphorus permitted by Mexico’s maximum legal limit. When Fusion Investigates asked for a response to these figures, the company said, “Celanese was not involved in the study. As such, we cannot confirm the validity of the data contained in the 2011 IMTA study.” Celanese told Fusion Investigates they had not exceeded national limits in 2014.

Huntsman sent Fusion Investigates the following response regarding their environmental practices at their plant in Jalisco: “Test results consistently show that effluent (chemical discharges) from the site operates within the regulatory limits set by Mexican authorities and Huntsman standards. Huntsman continues to adopt a proactive approach in developing innovative products that minimize environmental impact.” The company did not respond to questions about the State Water Commission report that found the company discharged four times more than the Mexican legal limit in phosphorus, three times over for biochemical oxygen demand (organic pollutants), and one time over the limit for nitrogen.

The Water Commission report also found Nestlé’s chemical discharge was five times over the limit for nitrogen and 19 times over the limit for phosphorus. When Fusion Investigates asked about these figures, Nestlé said, “From the beginning of our operations in Ocotlán, Jalisco, all emissions from this factory comply with the corresponding regulations.” In addition, the company told Fusion Investigates they are now compliant with Mexico’s environmental standards, due in part to a $3 million investment in a treatment plant.

Today, supporters of Miguel Ángel Lopez Rocha’s family continue to bring the boy’s case to government officials, but they find their pleas often fall on deaf ears. “It was finally proven that the contamination does kill,” said Raúl Muñoz Delgadillo, one of Lopez Rocha’s supporters and president of the Committee for Environmental Defense. “With an 8-year-old child, it cut off his right to enjoy his future — all for omissions of many institutions.” And while the Santiago River continues to attract wealthy industrial investors, those who live along it are left dealing with the consequences.

El Salto Municipal Mayor Joel Gonzalez García thinks the river’s population and the factories can coexist. He believes the factories follow the law. And the ones that don’t? “Well, the obligation of the municipal and state government is to demand that they comply,” he told Fusion Investigates. For Gonzalez Garcia, it’s a matter of faith. “We need to trust in the humanity and respect of the companies — that they will keep their promise and treat their waste.”

Meanwhile, the neighborhood where Lopez Rocha died remains much the same. With one change. Today, at the place the boy fell into the canal, stands a chain link fence. One small barrier protecting children from the toxic waters below.

Watch Silent River, a Fusion Investigates documentary about a young woman who defies death threats to combat the pollution of the Santiago River.

This story was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations, which awarded Steve Fisher an I.F. Stone Award. The report was also supported by the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley.