Last April in his mobile home, set back from the road on the outskirts of Haleyville, Alabama, Charles Rice reclined in his La-Z-Boy, lit a cigarette, and told me why he refused to socialize with nonwhites. I’d come a long way to find Rice, a man who happens to have been the star witness of a racially charged murder trial from 2001, for which a 20-year-old named Marlon Howell was sentenced to death. I was not Rice’s first unannounced visitor. For more than a decade, defense lawyers, prosecutors, police officers, and even a state’s attorney general have quietly sought him out to question him about his vexing and pivotal role in the Howell case.

Beyond the recliner, in the trailer’s small kitchen, a drawing of the Confederate flag decorated his refrigerator. Closer, on a mahogany stand, a full-size noose draped off a statuette of a Native American chief. Speaking with a restless excitement, Rice kicked his feet into the air. He told me he’d never known Howell because he was the “wrong breed.” Speaking of black people more generally, he said he didn’t “hang out with that type. I stay within my own race.”

“I’m not prejudiced,” Rice immediately clarified. “Don’t get me wrong. They’ve got just as much right to be here as I do, they bleed just as red as I do.”

But he would later tell me: “You seen one blue gum, you’ve seen ’em all.”

Even so, in May 2000, Rice picked Howell out of a police lineup composed of six young black men. Howell, who has continually maintained his innocence, stood accused of murdering a white man outside Rice’s home in New Albany, Mississippi. Without any physical evidence linking Howell to the crime, Rice’s identification became the most important piece of evidence in the state’s case against Howell. But Rice’s confidence in his own testimony has apparently wobbled over the years. In 2005, after being approached by one of Howell’s attorneys, Rice signed two sworn statements — one handwritten, one typed — recanting his identification of Howell, asserting that, “after much thought,” he had substantial doubts about his recognition of him that morning. Then, in 2007, Rice reversed his position again, swearing that he’d recanted under pressure and reaffirming his identification of Howell.

Rice’s testimony against Howell boosted the career of one of the South’s most notable politicians: In 2001, an ambitious district attorney named Jim Hood relied heavily on Rice to persuade an all-white jury to sentence Howell to death. Hood has since risen to become Mississippi’s attorney general, and he recently finished a term as president of the National Association of Attorneys General.

Today, Hood still boasts on his agency’s official website of convicting Howell and defeating a subsequent appeal. For more than a decade, Hood has used his position to aggressively ensure that Howell remains on death row — even as startling new evidence about the case has emerged.

Rice is not the only key witness to have recanted his original testimony to Howell’s appeals lawyer, only to withdraw the statement when contacted by prosecutors. In 2006, a woman named Terkecia Pannell submitted an affidavit swearing that two of Howell’s acquaintances, Curtis Lipsey and Adam Ray, had admitted to being the shooters. In it, Pannell also claimed that during the trial, after she told the district attorney that she would not lie on the stand and say Howell had a gun, “they never called me to testify.” Howell’s two co-defendants, who fingered Howell as the shooter, have also recanted crucial parts of their testimony and claim police pressured them into giving false statements. (Hood declined an interview request and then declined to respond to written questions, citing Howell’s pending appeal.)

- Rice's identification became the most important piece of evidence in the state's case against Howell.

Then, in 2013, a woman named Lasonja Gambles came forward claiming to be a key alibi witness for Howell. She alleged that a New Albany police officer had approached her outside her high school in 2001 and discouraged her from testifying at the trial. “He told me to not say a damn thing because it wasn’t important — he said everything had been taken care of,” she said in a taped interview with Howell’s attorney. “My mother always told me that sometimes you have to act ignorant around people, act like you don’t know anything because it’s safer that way.”

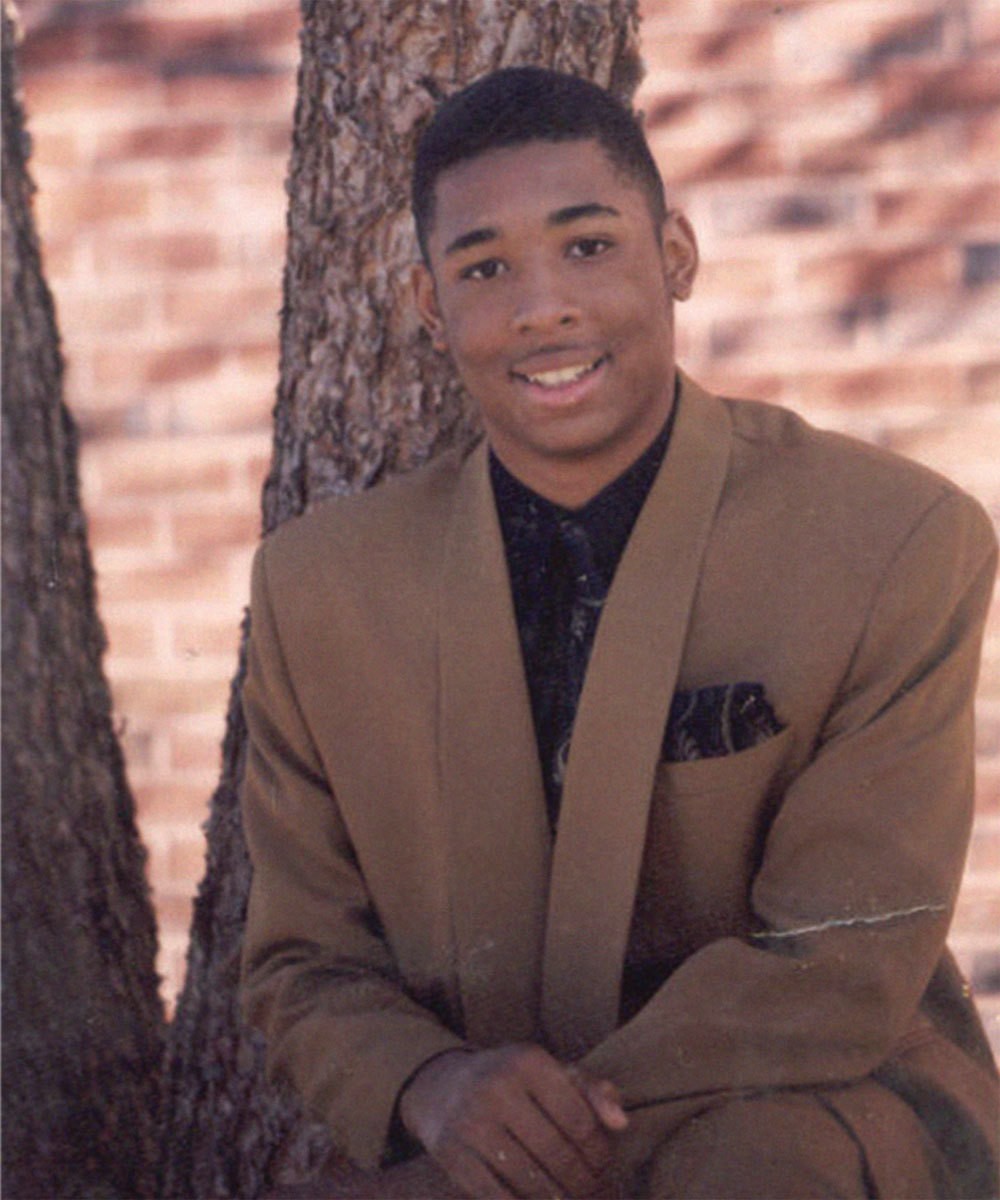

Marlon Howell in eighth grade.

Just before 5:15 on a Monday morning in May 2000, a single gunshot broke the predawn peace of New Albany’s Northside neighborhood, a working-class enclave of the prim, business-minded town of 8,000. Sixty-one-year-old Hugh David Pernell — a father of three children and a deacon at the local Presbyterian church — had been running his morning route delivering the town’s newspaper when he was pulled over by men in an Oldsmobile Cutlass. Someone walked up to his driver-side window and shot him through the chest. The bullet pierced his seatbelt and passed through his heart. In his last moments of life, Pernell attempted to flee. His car careened down a residential street, across a front lawn, and into a parked car. Pernell opened his door and fell to the ground. He died moments later.

Rice, who watched the crime unfold from his front window, called 911 and reported that a black shooter had made off in an old-model Cutlass.

Under the brightening sky, streetlights flickered off as police scoured the scene for clues. Aside from a smudged fingerprint on Pernell’s door and a spent shell casing found under the car’s fender, investigators had little evidence to work with. But within hours, police received a tip that a 19-year-old named Curtis Lipsey was involved in the shooting. The previous night, Lipsey had been driving around in a Cutlass owned by the grandmother of his friend Adam Ray, also 19. From there, the case developed quickly.

At around 7:30 that evening, after police had knocked on the door of Lipsey’s home and spoken with his sister, Lipsey and Ray turned themselves in. Ray would later tell a judge that his cousin had given him the .380 magnum pistol that police determined killed Pernell.

While the two friends were being interrogated at the police station, a 20-year-old named Marlon Howell was playing basketball near his family’s house in the neighboring town of Blue Mountain. Walking home at dusk, Howell saw a mass of police sirens illuminating his driveway. At first, he thought something had happened to his family, he said. Minutes later, he was handcuffed in the back of a police cruiser speeding along darkening two-lane roads toward New Albany.

His father was a Baptist preacher, but Howell’s disciplinary upbringing had not produced a devout teenager. With a quarterback’s build and goofy charisma, Howell was known as a class clown, and, in his late teens, he had become more interested in chasing girls, smoking pot, and playing ball than studying scripture. “Marlon loved girls,” his father, James Howell, told me. Eventually, Howell gained a reputation for openly dating white girls. “At that time it was a pretty big deal to date outside your race,” said Jaylan Buchanan, one of Howell’s closest childhood friends. “Me and any other guys he rolled with, we’d be on the low with that, but Marlon was out with it. He didn’t care.”

Howell’s focus on women led to trouble, large and small. “Once Marlon and I went on this church trip to Alabama and met these two girls and exchanged numbers,” recalled Eric Griffin, Howell’s cousin, who said he still considered Howell his best friend. Back home, he and Howell talked to the girls every day for hours. When the phone bill came back, “it was over five hundred bucks or something ridiculous that neither one of us could pay.”

During Howell’s junior year, a girl approached him through a high school acquaintance and asked if he could get her some pot. He did, but it turned out that she was working undercover for the local police. He had been targeted in a narcotics sting.

Howell, then 17, was charged as an adult for possession of 6.8 grams of marijuana. Instead of finishing his junior year, he spent three months in jail, and then a year under house arrest, allowed to leave only to work temp jobs intended to pay an array of court and probation fees. He struggled to keep gigs, and with his felony conviction, his managers refused to hire him full-time.

While Howell was confined to his parents’ home in Blue Mountain, Griffin began his freshman year at the University of Southern Mississippi, in Hattiesburg, some four hours south. In March 2000, after Howell was released from house arrest, he visited Griffin there. Seeing his cousin’s evolving life appeared to impact Howell. “He was on probation,” Griffin remembered, “and he was like, ‘Yeah, once I get this stuff behind me, I want to get my GED. I want to be like you, to go to school like you.'”

But on the evening of May 14, just weeks after that trip, Howell hopped in the Cutlass with Ray and Lipsey. Howell knew Lipsey from high school and said that he got into the car on a whim, hoping to go meet some “females” at a skating rink in Tupelo.

None of the interrogations that took place the following night were recorded or transcribed. Ray and Lipsey signed statements asserting that Howell had shot Pernell in a robbery attempt to get money to pay probation fees due the following day. Lipsey would later tell Howell’s jury that, in exchange for giving his statement, an agreement was made with the district attorney’s office to reduce his charge from capital murder to manslaughter and robbery. Lipsey and Ray had “picked Marlon Howell up on Northside in the early morning hours,” read a sworn interrogation summary by New Albany investigator Tim Kent, who played a lead role in the investigation, with “the intention of robbing someone on the streets of New Albany […] Howell told Adam Ray to ‘stop that car and I’ll take his money.'” Months later, Lipsey would tell the jury in Howell’s case that Howell had been desperate to find someone to rob — “a good little lick” — to cover the fees.

The next day, Rice picked Howell out of a police lineup.

Meanwhile, the news of Pernell’s murder had quickly spread. A longtime counterman at the New Albany post office, Pernell seems to have been one of the most well-known people in town. “Almost everybody in town had contact with him,” said Michael Reed, a longtime New Albany resident who served on Howell’s jury and who, as a child, played with Pernell’s children. “He was a very pleasant person.”

The murder rankled the community. “They ought not to even give them a trial,” one man told the local paper, referring to Howell and his co-defendants. A county commissioner would later tell the court that, in the days after Pernell’s murder, some New Albany residents wanted Howell lynched. Howell told me that during his interrogation he heard the town’s police chief, David Grisham, on the phone trying to calm several callers who seemed to want an execution to take place immediately.

- In the days after Pernell's murder, some New Albany residents wanted Howell lynched.

By many accounts, New Albany lived up to its motto of “the Fair and Friendly City.” Former employees of the town’s police department, several of them African American, and local attorneys all spoke of the town priding itself on having transcended the region’s ugly racial politics. But several current and former African American residents described another reality, what they believed to be systemic racial bias and harassment at the hands of local law enforcement.

For defense lawyers who practice across northern Mississippi, it’s not the city’s police department that stands out. It’s Union County’s predominately white, deeply conservative jury pool: “What’s the one jurisdiction you don’t want a criminal case in? It’s Union County,” said Victor Fleitas, an attorney in nearby Tupelo, who has defended clients in criminal cases across northern Mississippi. Fleitas said that Union County’s juries are so police-friendly it’s enough to keep criminal defendants from taking cases to court altogether.

Perhaps as a result, the town’s criminal justice system seems to operate almost wholly on plea deals. One retired detective I spoke with told me that out of hundreds, even thousands, of cases he worked on during his 25 years in New Albany’s police department, he got guilty pleas in nearly all. “I haven’t been to trial but three or four times out of all these years, because we made good cases and they pled guilty,” said the former detective. “If you do it right and you get it right, they’ll tell you the truth.”

The extremely few — about one defendant a year — who do take cases to trial face tough odds. The clerk of the county’s court system, Phyllis Stanford, told me that, in her ten years on the job, a Union County jury has not delivered a single not-guilty verdict. “Who actually takes a case to trial in New Albany?” Fleitas said. “You’re either off your rocker or really innocent.”

New Albany

Sensing a challenge, Howell’s father asked a friend named Duncan Lott, who practiced law in nearby Booneville, to represent his son, who they said had been sleeping at home at the time of Pernell’s murder. Although the family had little money to offer him, Lott took the case. Yet he struggled to pay his investigator to chase down leads, and the state rejected his plea for public funding for Howell’s defense. As the court date approached, Lott had found only two witnesses to support Howell’s alibi: Howell’s father and sister.

The state’s case was assigned to Jim Hood, a 39-year-old district attorney based in nearby Houston, Mississippi. As a prosecutor, Hood was intensely adversarial and effective. He would soon become known across the state for keeping his hair in a vintage fluffed mullet styled after the country singer Conway Twitty, for wearing a 9mm pistol to work each morning, and for his fierce support of the state’s death penalty.

Hood had no physical evidence linking Howell to the crime. And Charles Rice, the man who’d seen the shooting from his home, was the only eyewitness not facing execution. He became the sturdiest pillar of Hood’s case.

To buttress Rice’s identification, police chief David Grisham told the jury that although the sun had not yet risen at the time of Pernell’s shooting, “the sky was lighting up” and street lights and car lights would “greatly enhance your vision.” A medical examiner told the court that the bullet traveled through Pernell’s body in a manner consistent with what Rice claimed to have seen. Other forensic experts explained how common it is to lack physical evidence, like fingerprints or gunshot residue, linking a murderer to his crime. Grisham also told the court that Howell had a defense attorney present at the lineup, which generally would be required by state law to ensure that the process is fair.

Rice told the jury that while brewing his morning coffee, he heard a horn honk outside his house, and he parted his blinds to see a man approaching Pernell’s driver-side window.

“He flew his hands up in the air in a gesture, and when he brought his hands down he grabbed his pistol and shot him,” Rice told the court. “Then Marlon got into the passenger-side front seat and they took off.” Lipsey told the jury that Howell, sitting in the passenger seat of Ray’s Cutlass, insisted they pull Pernell over to take his money. “Marlon reached over blinking the lights on and off and trying to stop the car, and he told Adam: ‘Hurry up, come stop the car.'”

Brandon Shaw, a distant cousin of Ray’s, told the court that the three had burst into his house just minutes after the shooting, where he saw Howell effectively admit to the murder. Shaw led police behind his house to the .380 handgun, which he said Howell had hid. Hood also presented statements against Howell from one of Howell’s cellmates, Shaw’s brother, and a man named Marcus Powell, who claimed to have accompanied Howell on the ride home from Shaw’s house after the murder.

In all, Hood called 11 witnesses to support Howell’s guilt, including four expert witnesses. They spoke to the jury with a native authority and, like Rice’s own testimony, dead-set certainty.

Lott seemed less sure of his argument. Before Howell’s conviction, the defense called only five witnesses and did not summon a single expert to question the state’s case.

As is common for defendants in murder trials, Howell did not testify, and jurors I spoke with told me that the alibi his defense team constructed struck them as creaky, at times even contradictory. Howell’s father told the jury that he had opened the door to let Howell in at some point in the middle of the night — certainly while it was still dark out, he said — and Howell’s sister Miriam said that she had heard Howell ring the door bell, come into the house, and turn on the TV in the living room. This was all the jury heard from Howell’s defense team about his whereabouts that night. They never heard an alternate story of when and how Howell parted ways with his co-defendants.

During jury selection, Hood had struck the only two potential black jurors, and the all-white jury that heard Howell’s case was impressed by Hood’s performance. “It was like you were part of it,” one juror, an elderly woman who could remember almost nothing else of the case, told me of Hood’s vivid presentation.

On the trial’s fifth and final day, Hood stopped calling Howell by his name, referring to him instead as the “Big Chiefa,” derived from Howell’s teenage nickname. Hood painted Howell as a gang leader who coerced his acolytes into violent crime. “You heard his voice breaking,” Hood said of Lipsey’s testimony. “Scared to death of the Big Chiefa.” When the jury read the guilty verdict, Howell’s mother fainted and was removed from the courthouse on a stretcher.

During his closing argument at Howell’s sentencing, Hood’s oratory oscillated between the tough talk of a lawman and emotional appeals on behalf of the deceased. “I expect he would like to see this defendant sit on death row and locked down thinking about what will happen to him,” Hood told the jury. “I think he would at least want that.

“You are going to find that this man needs to die,” he admonished them, and later that afternoon, after roughly an hour of deliberation, the jury did just that. The judge set Howell’s execution for the following May 15, the one-year anniversary of Pernell’s death.

The New Albany police station where Howell was first questioned.

In 2006, as New Albany was moving on from the Howell case and Jim Hood was comfortably installed in the state capital as attorney general, the case against Howell slowly began to unravel.

After Howell was transported to death row, his two sisters canvassed local lawyers to take up his appeals pro bono. Striking out in Mississippi, they stumbled upon a personal injury and criminal lawyer named Billy Richardson, in Fayetteville, North Carolina. After meeting with the family, Richardson took the case free of charge and quickly became obsessed with proving Howell’s innocence.

Richardson, who is now serving his second term as a Democrat in the North Carolina House of Representatives, has the air of a Clintonian good ol’ boy: a Southern country-club type with a deep progressive streak and a trial lawyer’s eagerness to thrust himself into any situation.*

Over the course of a year, Richardson would make multiple trips to Mississippi to interview those who participated in Howell’s trial. By 2006, each key witness who had testified against Howell had, in sworn statements, recanted critical elements of what they had told the jury. And a new witness, Terkecia Pannell, had emerged to support Howell’s alibi.

Pannell, Shaw’s former girlfriend, said she’d been at Shaw’s house right after the shooting. In a detailed sworn statement secured by Richardson, Pannell asserted that, in the early hours of the morning, Howell’s co-defendants had indeed shown up at Shaw’s house, but Howell had not been with them. “Adam had a gun and they were acting scared, saying, ‘We shot a white guy,'” she said. “I tried to tell the district attorney what I really knew, but he kept trying to tell me what he wanted me to say.”

Pannell’s statement asserts that during the trial, at the courthouse, after she told the district attorney she would tell the truth on the stand, “they sent me home and said they would call me if they needed me.” Lott, Howell’s defense attorney, had not bothered to interview Pannell and was not informed of her allegedly having been turned away from court that day.

Even more significantly, Richardson secured two affidavits from Rice swearing that he had doubts about his identification of Howell on the lineup. Rice’s statement said that he’d discussed the concerns with his wife, who would later sign her own affidavit corroborating this.

Recognizing that Howell’s case largely rested on Rice’s testimony, Richardson hired an expert on perception and memory who concluded that, from some 70 feet away at the predawn hour of Pernell’s shooting, it would have been impossible for Rice to have seen the shooter’s face clearly enough to make a reliable identification.

Richardson also discovered that Lott had never run a background check on Rice, which would have revealed an extensive criminal history including auto theft — information that could have been used to impeach his credibility. (In 2005, Lott signed a sworn statement affirming in lacerating detail his failure to adequately represent Howell.)

Richardson provided an alternative explanation for why Rice was able to pick the police’s lead suspect out of the lineup: As a general rule, a suspect is not supposed to stand out in a police lineup. But in Howell’s case, he was not only the tallest member of the lineup, but also the only one wearing shoes; the rest wore standard-issue jail sandals over bright white socks. Police also never gave Rice an opportunity to identify either Lipsey or Ray.

Mississippi state law generally grants criminal suspects the right to have an attorney present when facing a lineup. In 2001, Grisham, New Albany’s police chief, told the court that Reagan Russell, a local defense attorney, had represented Howell at the lineup. After Richardson discovered this to be false in 2005, Grisham filed a sworn statement asserting that a different attorney, Thomas McDonough, had been present. This also turned out to be untrue, which both defense lawyers asserted in affidavits for Richardson and confirmed to VICE. Howell had no representation at the lineup. (Grisham declined to comment on this matter.)

Disputing both Richardson and Lott’s contention that Howell stood out in the lineup, state judges have relied on the police department’s claim that another lineup participant, Robert Harris, then 22, was six foot two, just like Howell. Yet in the lineup photograph, Harris appears shorter. When I contacted Harris, who knew Howell before his arrest, he expressed surprise at the police department’s claim. “He was way taller than us,” Harris said of the lineup. Harris insisted that he was no taller than six feet in May 2000. (He said he is now just shy of six foot one.) “It was not fair, it didn’t look fair — he’s always been taller than I am.”

In June, I sent a photograph of the lineup to Gary Wells, a professor of psychology at Iowa State University and a leading expert on police lineups. Although I’d given him no information about the case, he picked Howell out immediately as the suspect. I told Wells he had chosen correctly.

“Hey, if I can do it, or if a person off the street can do it, and we didn’t even witness the crime, what does it mean that the witness can do it too?” Wells said, pointing to Howell’s size and his shoes. “Why didn’t they just tell him, ‘Hey, the guy we think did it is number three’?”

A year before Howell’s arrest, the federal government had enlisted Wells to help create lineup guidelines for police departments across the country.

“I don’t think they really have an excuse that back then no one really knew,” Wells said. “By 2000, the US Department of Justice report that we worked on had been distributed to every law enforcement agency in the United States, saying, ‘Don’t do this, don’t do what you did right here.’

“So the question here would be, what other evidence do they have?”

*Howell’s is not the first death-penalty case that Richardson has litigated. In 1989, he helped to win the exoneration of Tim Hennis, a soldier who had been convicted of raping and killing a mother and murdering her two daughters. After DNA evidence later re-incriminated Hennis, he was placed back on death row.

Miriam Howell, Marlon’s sister, near her home in Myrtle.

If Hood presented Rice’s testimony as the smoking gun, he depended primarily on the testimony of Howell’s co-defendants to answer the question of motive. The assertion that a depraved robbery attempt had caused Pernell’s murder underpinned Hood’s narrative of the crime. But in 2005, Lipsey and Ray each signed sworn affidavits saying they had been pressured into making their original statements, which were inaccurate. In the recantations, the pair asserted that they hadn’t seen the crime occur, that they didn’t know who had killed Pernell, and that Howell had not mentioned robbing anyone.

At the 2001 trial, Lipsey testified that during his first interrogation, on the night he was arrested, he initially told police he’d been “asleep” in the back of the Cutlass and hadn’t seen the murder. According to Lipsey’s testimony, one of the officers, a young detective named Tim Kent, discarded the statement. Lipsey said that Kent, who is now the mayor of New Albany, then allegedly told Lipsey that Howell had already been arrested and had accused Lipsey of pulling the trigger. Neither had actually happened, but Lipsey said he then gave a second statement. The statement of Lipsey’s that police put on file, which directly accused Howell, would provide the basis for the state’s theory of the crime. (Kent, saying the Howell case “is what it is,” declined an interview request and did not respond to written questions.)

“Between the intoxication, threats, and them telling me Marlon had lied on me, I gave the police what they wanted,” Lipsey said in his recantation, made from prison, where he is serving 35 years for his role in the shooting. “Also the police kept pushing me about a robbery. Marlon never, ever mentioned robbing anyone,” the affidavit continued. “I felt trapped into standing by my second statement at trial even though it was wrong.”

Ray, who signed a similar recantation during an interview with Richardson, called me from prison, where he is serving 30 years for his part in Pernell’s murder, and affirmed his 2005 recantation. (At trial, Hood told the jury that he would not call Ray, who has a low IQ, because “that boy is not all there.”)

“They was pressuring me,” Ray told me of his police interrogation, “trying to scare us with those scare tactics.”

Ray also insisted that Howell had not said anything about robbing anyone that night. He believed they pulled Pernell over because he thought Howell “knew this person or something.”

Although Ray said that, after hearing the gunshot, he remembers Howell jumping back into the Cutlass — which contradicts Howell’s version of events — he also said he was so intoxicated that night he couldn’t recall the events properly. When I asked Ray who he thought killed Pernell, Ray said he had not seen the murder and simply did not know.

Shaw, who led police to the murder weapon, gave Richardson a sworn statement in 2005 recanting his court testimony that he’d saw Howell go behind his house with the gun. The statement instead said that Lipsey and Ray had simply told him where the gun was.

Lipsey and Ray’s interrogations also provided the basis for Hood’s descriptions of Howell as a gang leader. Friends and acquaintances of Howell’s I spoke with said that Howell, whose prior criminal record consisted only of the marijuana conviction, never belonged to anything resembling a gang, much less served as a gang leader. “There are no gangs in New Albany, so I’m not sure what gang he could have been leading,” said Taliah Hasan, who is now attending law school in Michigan and knew Howell through a close friendship with his sister Miriam. “It was a tactic for his prosecution,” she said. “People called him ‘Chiefa’ because he smoked a lot of marijuana,” Hasan said. “‘Chiefing’ means smoking. [Hood] completely misinterpreted the name.”

The notion that Howell was seeking to rob Pernell was also bolstered by Hood’s repeated assertions that Howell refused to work for an honest living.

Yet, as Howell’s sister Apprecia Prather pointed out, in the years before Pernell’s murder, Howell had in fact kept a variety of jobs. While on house arrest, for instance, Howell had done temp work at a Walmart distribution warehouse; his application to work full-time was denied because of the pot conviction.

“The picture [Hood] painted,” said Prather, “was of a law-abiding Mister Pernell, an innocent man who worked for a living and had a family, versus a black boy, lazy and not working.

“We were puzzled, sitting there dumbfounded.”

Reverend James Howell and Linda Howell, Marlon’s parents, at church in Falkner.

In the nearly 12 years he has served as Mississippi’s attorney general, Hood has won acclaim for aggressively pursuing major players. He took on a BP operative after the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe, has antagonized Google, and, in 2005, prosecuted a former Klansman for orchestrating the murder of civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi. He is the only Democratic attorney general in the Deep South, and he has taken a number of progressive stances that are wildly unpopular in conservative Mississippi. This past June, for instance, Hood declined to represent Mississippi’s governor, Phil Bryant, in opposing the Supreme Court’s Obergfell ruling, which legalized same-sex marriage across the country.

His confidence as a Southern Democrat may be linked to a personality so brash and effective as to transcend party identity altogether. Yet he also tempers his more liberal positions with an exuberant embrace of core elements of the conservative credo. Hood’s support for Second Amendment rights is eclipsed by an almost fanatical pursuit of death-penalty cases.

Around the time Hood assumed office, for instance, new evidence emerged in the capital case of Michelle Byrom, who had been condemned to die for the 1999 murder of her abusive husband. It turned out that a judge had allegedly hidden confessions to the murder by Byrom’s son. Despite this information, which pointed strongly to Byrom’s innocence, Hood’s office argued against even holding a hearing to examine the new evidence and, instead, asked the state to execute her immediately. This past June, after making a plea deal, Byrom walked free after 16 years on Mississippi’s death row.

Byrom isn’t the only person to walk free from a death sentence. Since 1973, 155 death-row inmates have been exonerated in the US, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a tally that does not include people like Byrom who are freed as a result of plea deals. In a survey of more than 300 wrongful convictions that were overturned by DNA analysis, the Innocence Project found that more than 70 percent involved eyewitness misidentification. Last year, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presented a “conservative” estimate that suggested that upward of 100 current death-row inmates in the US are innocent.

In 2008, Mississippi’s supreme court ordered that a hearing take place to determine whether Howell was indeed entitled to another trial. Ahead of the hearing, which wouldn’t take place until March 2013, Richardson believed he had a slam dunk. “What more do you need to prove?” Richardson said. But weeks before the court date, Richardson learned that Jim Hood himself would travel to New Albany to defend his 12-year-old case.

Hood’s presence posed a number of challenges for Richardson’s team. To have Mississippi’s top lawman in the courtroom personally defending the state’s case meant Richardson would be facing significant firepower. Richardson considered Hood himself to be a witness and worried that, acting instead as a litigator, the attorney general would be able to address the court record without being put under oath or subjected to cross examination.

Hood would also be in the position of personally questioning people who would be making accusations that involved his office’s conduct back in 2001.

In the weeks before the hearing, Hood made swift preparations. His agents paid visits to those who, years before, had recanted their original testimony to Richardson. By the time of the hearing, his office had gotten key witnesses to reverse their recantations.

Having accused Howell’s district attorney of hiding her witness testimony in 2001, Terkecia Pannell’s statement most directly implicated Hood in a serious breach of conduct, and she would become the target of some of his most aggressive courtroom tactics. After she took the stand and was waiting on call in the courthouse witness room, the attorney general persuaded the judge to allow him to personally interview Pannell in a back room. This was not the first meeting she had with Hood’s office, but it is the only one that was attended by a member of Howell’s defense team, a Tupelo-based attorney named Jim Waide.

“It wasn’t an interview more than it was just a rage against her,” Waide told me. “It would have been enough to frighten me, and I’m a lawyer.”

Speaking to the judge after emerging from the meeting, Waide said that Hood had told Pannell: “Did you know the penalty for perjury? You have another opportunity to tell the truth — to avoid legal entanglements and to tell the truth.”

According to Waide, after Pannell continually told Hood that she had already told the truth, Hood responded: “Well, you’ve failed a polygraph.”

It turned out that, over the preceding two days of the hearing, Hood had administered successive lie detector tests on Pannell at the courthouse.

“I think a lie detector test in itself would be very intimidating,” said Waide, who has won three cases before the US Supreme Court and who, like many in the legal profession, places little faith in the reliability of polygraphs. “When we’ve got somebody’s life at stake, I just don’t think it’s appropriate to be intimidating witnesses.”

On the stand Pannell had made a poor witness. After initially affirming her affidavit of Howell’s innocence, she wavered under the prosecution’s questioning. By the end of her testimony, she said she simply could not remember the events with complete certainty.

Other witnesses Richardson called further damaged his case. Charles Rice, who had witnessed the shooting, told the court that Richardson and his investigators had come to his house the night before his wedding and badgered him into recanting his identification of Howell. He said that when they came back two days later, he signed an additional sworn statement in order to get them out of his hair.

When read his recantation point-by-point, Rice told the courtroom that every element of it suggested that his uncertainty was false. He said he was certain, with no doubts at all, about the accuracy of his identification of Howell.

Brandon Shaw told the court he had given a false recantation after being pestered by Richardson and his investigator, who he claimed had given him $20 in exchange for agreeing to meet. “I wouldn’t say he offered me money to change my testimony,” Shaw said, “but it was like he was trying to bribe me.”

Richardson confirmed that this happened, but said it was to reimburse Shaw’s costs for speaking with him; Shaw had taken roughly two hours off from his job washing cars. (When I found Shaw outside his New Albany home last April, he told me simply that his recantation was not accurate and declined to discuss the case any further.)

In just three days, nearly a decade of Richardson’s work had crumbled.

The courthouse in New Albany, where Howell was tried for the killing of Pernell.

There is no doubt that, just for peering out his window during the brief seconds of Pernell’s murder on that May morning, Rice has endured 15 years of headaches. He has been repeatedly questioned by Howell’s attorneys, state prosecutors, and Attorney General Hood. He told me that his then wife made them move out of the New Albany house after a dead dog was thrown onto their porch following the murder. Approaching Haleyville, I imagined the key witness would simply send me away. The furious — living — dog that greeted me in front of Rice’s trailer only deepened my misgivings.

Yet after his current wife chained the animal, Rice beckoned me through a screened door into his living room. To my surprise, he seemed eager to speak about the case. “Old Howell back in the program, huh?” Rice said. Then, without prompting, he reaffirmed his identification of Howell. “That boy is guilty as the day is long,” he told me. “That boy deserves to die.”

Rice lit a cigarette and repeated what he had told the judge at the Union County hearing two years prior: that Richardson had pressured him to recant. “They just pounded the hell out of me,” he said. “I couldn’t pry them sons of bitches from my house!

“It was an onslaught,” he continued. “I mean there were three people right there and all three of them shooting the same questions. It was designed to turn me around, and it did a pretty damn good job of it.”

At one point, clearly exasperated by talking about Howell, Rice exclaimed: “I’m tired of that man fucking with my personal life!”

Richardson said that he can be a persistent questioner but claimed that Rice’s recantation was genuine. It is a claim that cannot be confirmed for certain: Richardson’s team did not record the conversation in which Rice agreed to recant. Richardson believes that the case now largely comes down to Rice’s credibility, and the lawyer keeps a mental encyclopedia of reasons to doubt the central witness.

Speaking with me, Rice gave vivid descriptions of the murder and maintained that he recognized Howell the second he saw him in the lineup.

In April, at a McDonald’s at a truck stop outside Tupelo, about an hour drive from Rice’s home, I met a private investigator named Leonard Sanders, who, years before, helped take the exculpatory statements of Pannell and Rice. Sanders said the two had spoken of their own free will, had not been badgered, and appeared to be telling the truth. “Working for lawyers, I’ve destroyed their cases many, many times,” Sanders told me. “I had no vested interest in this one way or another, but as it went along I became more and more convinced that Marlon Howell was wrongly convicted.”

Rice’s ex-wife, Melody Burns, also signed a sworn statement during a meeting with one of Richardson’s investigators saying that, in private conversations, Rice had expressed doubts about the accuracy of his identification of Howell. During his interviews with Richardson, which she witnessed, her statement reads, Rice had not been pressured into recanting. In addition to his concerns over the lineup itself, “he was also haunted by the fact that he saw only two people in the car, including the shooter,” Burns’s affidavit stated.

I could not locate Burns. Chuck Mims, a retired police chief and Richardson’s primary investigator in North Carolina, told me that after she was contacted by Hood’s office just before the 2013 hearing, Burns decided to withdraw from the case. “She said she was through with it,” Mims told me, “that she was scared and wanted to have nothing else to do with it.”

B-Quik in New Albany, Mississippi, where Lasonja Gambles says she picked up Howell before the shooting.

In 2013, while on tour with a traveling carnival, a circus elephant was wounded in a drive-by shooting in Tupelo. The elephant was expected to make a full recovery, but the seemingly deliberate attack on the exotic animal captured national headlines.

News of the drive-by reached a woman in South Carolina named Lasonja Gambles, who grew up in Blue Mountain and had been friends with Howell. Reading local coverage of the shooting, she noticed a story about Howell’s evidentiary hearing in nearby Union County. That’s when, she said, the events of that night came rushing back.

Gambles posted in the comment section of a local news story about Howell’s hearing that she had information proving that Howell was innocent. Mims, Richardson’s investigator, contacted her almost immediately.

In her affidavit, Gambles asserted that she’d picked up Howell at a Northside gas station hours before Pernell’s murder happened. As she returned home from dropping Howell off, her statement said, the sky was still dark. (The shooting took place just as the sky was lightening.)

Since the 2013 evidentiary hearing, the quality of Richardson’s affidavits have become a central question in the case. So, with no luck reaching Gambles, I asked Richardson for more information about her statements. Mims sent me two DVDs of his interview with her. In the tapes, a confident and grave Gambles tells a detailed story of driving Howell home in the wee hours and then, for more than a decade, being too afraid of retribution from police to speak about it.

Gambles, then 18, had known Howell in high school and said that, around the time of the murder, Howell’s then girlfriend had suspected Gambles of having romantic designs on Howell. At some point between 1:30 and 3 the morning of May 15, 2000, Gambles said, Howell called her from a pay phone at the B-Quik gas station on Northside, less than a mile away from the scene of Pernell’s murder. Upon picking him up, a visibly shaken and crying Howell told Gambles that Lipsey and Ray were “acting crazy” and going to hurt someone, she said. On the car ride to Blue Mountain, Gambles recalled, Howell said something had already happened or was about to occur that he wanted no part of. “I think he said it was ‘about to happen,'” she later told Richardson. She said that, after dropping Howell off at his house, she drove home and went to bed while it was still dark, but she couldn’t sleep “because I knew something wasn’t right.”

Gambles said that, weeks later — months before Howell’s trial — as she was preparing to take her senior-year final exams, a tall, heavyset New Albany police officer with a gray beard approached her outside her school. “He told me not to say a damn thing,” Gambles said, “that it had already been taken care of and they’d given him time.” Gambles feared that police might retaliate against her for speaking out, she said, especially after 2003, when she had her first run-in with the law for a marijuana charge. “I was afraid they were gonna try to pin something on me and lock me back up,” she said.

When asked why Howell wouldn’t have given her name, perhaps the most vexing question associated with her emergence as a potential witness, Gambles said she had been taught growing up that elements within the New Albany Police Department were deeply vindictive and speculated that Howell was seeking to protect her. Richardson said that, with his focus on all the other elements of the case, he never asked Howell straightforwardly how he’d gotten home that night.

On the tape, Gambles insists her story is genuine. “I put this on my life,” Gambles says. “I don’t have nothing to cover up. I’m tired of hiding, and I’m tired of keeping quiet. I have to get this off my chest.”

Gambles’s affidavit provides the main thrust of Howell’s final round of state-level appeals, filed in July by Richardson, his son Matt Richardson, Waide, and the Mississippi Innocence Project, an organization affiliated with the University of Mississippi School of Law that aims to exonerate the wrongfully convicted. In mid September, a separate set of lawyers with the New Orleans–based Promise of Justice Initiative filed the first of Howell’s appeals to a federal court.

The federal filing asserts Howell’s innocence but also challenges the legality of his death sentence. The appeal contends that Howell’s 1999 marijuana conviction was in fact illegal. According to Mississippi law, because Howell was a minor at the time of the arrest, he should only have faced a misdemeanor punishable by a $250 fine, the appeal states. Trying Howell as an adult had direct bearing on the death sentence he received two years later, as the jury, after convicting him of murder, was instructed to consider his probation status as one of the two aggravating factors in his death sentence.

The state has until mid November to respond to the federal appeal.

Howell said he meanwhile spends his days watching TV news and reading his subscription to Time, paid for by Richardson’s daughter. He told me that he is allowed outdoors at Mississippi State Penitentiary for one hour each day, but the excursions provide little respite. He is shackled and led to what he likens to “a dog cage,” which, he said, is not much larger than his cell. “They put you in there with a lock on the door and allow you to walk around.”

In April, I awoke to a mass text message from Howell’s sister Miriam. Her youngest brother had turned 35. “Good morning! Join in with me today in sending out a birthday shout out and pray for Marlon Howell,” she wrote. “Pray for his victory, strength, joy, and that he holds his hope.”

During our conversations, Howell typically remained focused on my questions and rarely extolled his innocence. But last March, as the prison phone system notified us that only 15 seconds remained on our call, Howell lost his usual composure.

“You got to understand,” Howell told me. “It’s been fifteen years of an ongoing lie. I’m in prison, man. They’re trying to kill me.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations and appearsin VICE Magazine‘s October Prison Issue.