My small feet thump the concrete as I hurry toward the door. My four older brothers trail closely behind. Upon entering, we disappear into the apartment and excitedly explore every corner. We peek out the window at our new playmates. By morning, the scent of bacon wafts into my bedroom. I look over at the floor beside my bed, where I’d asked my dad to sleep the night before. He’s not there. I don’t cry this time. I suspect he’s nearby, in the kitchen, responsible for the clanging pots. I venture out and there, amazingly, he is: my dad, standing over the stove, pushing frozen hash browns from side to side in the skillet. My brother is whisking eggs in a bowl, and I arrive just in time to put the biscuits in the pan. When breakfast is ready, my dad locks his hazel eyes on us and says, “You kids eat first.”

I was almost 4 when asthma finally sucked the last breath from my mom. After that, Dad made this ritual of “big breakfast” a weekend tradition. This weekend with him was special, though; we lived with Grandma by then, and we were visiting him in a furnished apartment on the grounds of Soledad State Prison as part of the California Department of Corrections’ Family Visiting program.

At least four times a year, my brothers and I were allowed to spend a weekend there with my father, who began serving 16 years to life when I was 5. The night before our visits, I anxiously folded my new pajamas; my grandmother refused to let me sleep in my usual oversize T-shirt while visiting him. Those weekends rate as some of the best moments of my childhood.

Going to prison is often an isolating event. It is assumed that once a person is incarcerated, their former life will simply vanish. But for the kids they leave behind, it doesn’t work that way: That prisoner remains a parent. Among the many collateral consequences of mass incarceration is its impact on children, and the number who are affected is staggering. According to a 2010 study (the most recent data available), 54 percent of the people serving time in US prisons were the parents of children, including more than 120,000 mothers and 1.1 million fathers. Over 2.7 million children in the United States had an incarcerated parent. That’s one in 28 kids, compared with one in 125 about 30 years ago. For black children, the odds were much worse: While one out of every 57 white children had an incarcerated parent, one out of every nine black children had a parent behind bars.

After my own father’s sentencing, our love was cocooned in collect phone calls, pictures, weekly letters, and cards on special occasions. These are the fibers that now connect a child to an incarcerated parent. The extended family visits that allowed my brothers and I to have “big breakfast” with Dad are fast disappearing from state corrections systems. Nine states once allowed them; today, they are widely offered in just four. In 1996, California eliminated visits for families like mine; I was 15 at the time. In Mississippi, where “conjugal” visits debuted almost a century ago, the corrections system ended the last of its family and spousal programs last year. A once extraordinarily progressive policy has been sacrificed due to prison overcrowding and state budget cuts — as well as to racist ideas about black sexuality.

Victoria Phillips, of Raleigh, Mississippi, calls out to her sleeping daughters and gives them a gentle nudge. “It’s time to get up,” she says. “Mama, we going to see Daddy?” the girls mumble, still groggy. Soon they’re getting dressed and heading out to the car. Phillips nods to the dark sky and eases her tan Impala onto the lone highway for the three-and-a-half-hour drive to the prison in Parchman. She turns on the radio as they pass several country towns dotted with catfish farms, cotton fields, and cow pastures.

Prison visitation varies from state to state and prison to prison. Typical visits, called “contact visits,” take place in designated areas with tables, chairs, and vending machines filled with junk food (and, in some cases, games to play). These visits take place under surveillance and allow extremely limited physical contact — usually just a hug and a kiss, lasting under 15 seconds, upon entry and exit. Children often make long treks for that fleeting moment — on average, 100 miles.

Victoria Phillips with her daughters Amari (right) and Rihanna. Phillips takes the two girls 180 miles across Mississippi so they can visit their dad in prison.Image: CAROLYN DRAKE/MAGNUM PHOTOS

Phillips describes her daughter Amari, 8, as a “daddy’s girl.” Amari speaks to him regularly by phone, gushing about her day at school or asking for a new doll. But the only time she ever sees or touches her father, who is serving a life sentence in the Mississippi State Penitentiary 180 miles away, is during these monthly contact visits.

They arrive by 7:30 am, so the wait in line is only 30 minutes. Bashful and petite, Amari rubs her eyes, shakes her russet ponytails, and smiles as she eases out of her seat belt. Once inside the prison, she walks through the metal detectors with familiarity. She knows it’s the only way she can see her dad, and she’s happy to oblige.

I remember rebelling at this process when I was her age. “Why do I have to take down my hair?” I demanded as my brother helped undo my new braids. But it was a requirement to get past the prison deities. They didn’t care that I was a small child; my father was in prison, so surely I could have small vials of heroin tucked in the folds of my French braids.

I remember rebelling at this process when I was her age. “Why do I have to take down my hair?” I demanded as my brother helped undo my new braids. But it was a requirement to get past the prison deities. They didn’t care that I was a small child; my father was in prison, so surely I could have small vials of heroin tucked in the folds of my French braids.

Amari doesn’t seem aware of the prison guard’s watchful gaze, which follows her as she moves around on her father’s lap. But Phillips always feels the stare. Amari sits with her dad, sharing a bag of chips while writing down the words she has recently learned to spell. Phillips says that standard visiting facilities at Parchman lack the coloring books, games, and outdoor activities that the last prison offered, so she now takes the girls there only once a month and reserves one additional Sunday just for her and her husband.

Until September 2012, the family had access to something else entirely: Mississippi’s Extended Family Visitation program. They made unsupervised visits that lasted for three to five days and took place on the facility grounds, in small apartments like the ones I remember from my own childhood.

“It was more like you were at home,” Phillips recalls wistfully. “It was more freedom.” She and her husband participated in the program for nearly six years, first as a couple and then, once their children were born, as a family. They barbecued together under the Mississippi sun. Amari played basketball with her dad and challenged him to cartwheel sessions. Etched in Phillips’ memory is the sight of Amari lying on her father’s chest watching cartoons after breakfast, or the nights when she helped him wash dishes and later fought sleep as he read her bedtime stories. Those visits were an essential part of Amari’s life.

It was here in Parchman, no later than 1918, that the Mississippi State Penitentiary — 18,000 acres of delta plantation that was then devoid of high walls or gun towers — became the birthplace of conjugal visits, which led the way to extended family visits. Started informally, these visits weren’t originally intended to unite spouses or connect families, but rather were based on racial stereotypes. Black men were thought to have superhuman strength and uncontrollable libidos. So conjugal visits were introduced to tame them and make them work harder at slaughtering hogs and picking cotton in the prison’s farming operation, according to historian David M. Oshinsky’s book Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. At the time, marriage wasn’t a prerequisite, and prostitutes visited the prison on Sundays. Beginning in the 1930s, white men were also allowed conjugal visits, and by 1972, women were too.

In 1961, inmate construction crews began building new conjugal-visiting facilities, and in 1963 the prison added marriage as an eligibility requirement. Back then, state prison officials reasoned that “a man and his wife have the right to sexual intercourse, even though the man is in prison,” according to Columbus B. Hopper’s 1962 study of the program. Prison officials believed that allowing these visits helped to ensure inmates that their families were well. “One visit in private is better than a hundred letters because he can judge for himself,” said one corrections officer, according to Hopper’s report. Hopper noted that, “with adequate facilities, careful selection, and appropriate counsel, it is possible that the conjugal visiting program in Mississippi could be developed into one of the most enlightened programs in modern corrections.”

In 1974, Mississippi arguably did just that when it launched the Family Visitation Program. These new visits lasted from three to five days and were open to parents, siblings, and children as well as spouses. The program, an effort to rehabilitate inmates and strengthen their family ties, made use of small apartments furnished by donations from the prisoners’ families and local stores. A 1975 letter from a Parchman prison superintendent to a community-relations associate touted the institution as among the most progressive prisons in the country. “The fact that conjugal visiting is believed to help in keeping marriages and families from breaking up makes the people of the state not only accept the practice but take pride in it as well,” it read.

- As Linda struggled to stitch together her separated clan, family visits were the seam.

Seeking both to strengthen the family and to quell prison upheaval, a number of states followed Mississippi’s lead in the coming decades. In 1968, California launched its Family Visiting Program at the California Correctional Institution at Tehachapi and soon expanded the program throughout the state. South Carolina introduced family visits around the same time. New York started its program in 1976, and Minnesota began its own in 1977. Similar ones followed in Washington, Connecticut, New Mexico, and Wyoming in the early 1980s.

Family and conjugal visits were never handed out like Halloween candy. In Mississippi, for instance, only minimum- or medium-security inmates who demonstrated good behavior were eligible to participate. They had to be tested for and free of infectious diseases. They couldn’t have any “sex-related” convictions on their records. Conjugal visits were permitted only for married inmates, once a week, and only for a single hour.

Still, the steady movement toward keeping families united in spite of incarceration began to reverse in the 1990s, when a new, more punitive approach took hold in corrections. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which implemented mandatory-minimum sentencing enhancements, the widened use of the death penalty, and limited amenities and services for prisoners, including access to higher education. The following year, the No Frills Prison Act eliminated such prison “frills” as weight-lifting equipment, most unmonitored phone calls, hot plates, and personal clothing. In 1996, Congress awarded grants to states that made prisoners serve as much of their sentenced time as possible.

The mid-1990s also marked the elimination of several conjugal and extended-family visiting programs. With a ballooning state-prison population, resources were scarce. In 1994, South Carolina’s conjugal visits appeared to have been the first to go. “As our new era in corrections begins,” read an annual corrections report, “the South Carolina Department of Corrections has taken note of the growing trends for tougher restrictions on inmates.” When Wyoming closed its Family Visiting Center in 1995, the prison warden said: “Times and conditions have changed since the program was first implemented. With the increasing population, greater security responsibilities, and limited budget, utilizing employees and other resources to maintain the family visiting program can no longer be justified.”

Over the next two years, Washington and California initiated severe restrictions on family visits, disqualifying a large population of inmates. In California, anyone with a life sentence who didn’t have a release date within three years was excluded. For me, that meant the end of privacy with my father. Not even my father’s written love tribute, “nakupenda malaika,” was private; the language lessons he sent me in Swahili were flagged and read by the sergeant. At least, I figured, the sergeant would know how much my father loved his angel.

Mississippi, where it all began, ended extended family visitation in 2012 and conjugal visitation in 2014. Today, only California, Connecticut, Washington, and New York continue to offer family visitation widely. South Dakota, Colorado, and Nebraska have a very limited visitation policy: only for female inmates, and focused on those with young children.

Phillips never received an official notice that family visits had been eliminated, although this meant a radical reshaping of her family’s life. Instead, a memo taped to the visiting-room wall announced the change. “I was mad!” she recalls. But instead of anger, her voice now aches with disappointment. “It felt terrible, because you don’t get that one-on-one time — you don’t get to wake up near your spouse.”

Christopher Epps, then the Mississippi corrections commissioner, explained in a press release that he’d cut the program for budgetary reasons, citing costs like building maintenance and the time that staffers spent escorting inmates to and from the visitation facility. Then he pivoted to another concern: “Even though we provide contraception, we have no idea how many women are getting pregnant only for the child to be raised by one parent.” Epps concluded that “the benefits of the programs don’t outweigh the cost.”

- Keshawn Green: “Some people in [prison] may never get out, and they need another piece of them out here living.”

Asked about New Mexico’s decision to end family visitation last year, Alex Tomlin, the corrections department’s public-affairs director, inadvertently described what was, to me, the beauty of the program: “The majority were not spousal visits — they were [visits] with children or parents.” For example, she offered, “an offender and his children, they would play football in the front yard.” She added that only 200 of the approximately 7,000 state inmates were eligible, a population too small to be worth the $120,000 annual cost. And yet, in 2014, the program accounted for less than 1 percent of the department’s $293 million budget.

“If we could show it actually reduced the recidivism, then we would have kept it,” Tomlin said. But while there’s no study using a strong research design that specifically links extended family visits with either reduced recidivism or stronger family bonds, a number of studies have consistently linked regular visits with both. In 2011, for example, the Minnesota Department of Corrections conducted an in-depth study that tracked over 16,000 offenders released from the state’s prisons between 2003 and 2007. When other factors were controlled, the study showed that prisoners who received visits were 13 percent less likely to be convicted of a felony after their release, and 25 percent less likely to have their probation or parole revoked. Another 2009 study evaluated the effects of prison visitation in the Florida correctional system and found that prisoners who received visits were less likely to recidivate.

Some states have acknowledged these positive outcomes. The Washington State Corrections Department, which continues to offer extended family visits, has said that they “support building sustainable relationships important to offender re-entry and to provide an incentive for those serving long-term sentences to engage in positive behavioral choices.”

With studies indicating such striking benefits, and with such a small financial savings at stake, what is really at work? The debate in Mississippi is telling. Take Richard Bennett, a Republican state representative who for three straight years wrote bills seeking to ban conjugal visits, before the corrections department finally decided to end them on its own in 2014. “It’s unfair to have a child without a parent,” Bennett contends. “Taxpayers are paying for it. I don’t think it’s right. I think you’re in prison for a reason — you’re in prison because you did something, and there is a price to pay, and that’s part of the punishment.”

Amari Phillips is too young to comprehend that she was conceived in prison. But Keshawn Green, 20, has thought a lot about what it means for him that he, too, was conceived during a prison visit — and also what it means for his father, who has served 34 years of his life sentence. And in Mississippi, a “life sentence” means just that: to the end of a prisoner’s natural life span. “God gave me this life,” Green says, holding my eyes with a steady gaze. “Some people in there may never get out, and they need another piece of them out here living.” Green views his parents’ four-decade union as a “blessing” despite the barriers imposed by father’s incarceration. But he suspects that corrections officials have no idea what it’s like “when you can’t tuck your kids in or know that your wife is safe.”

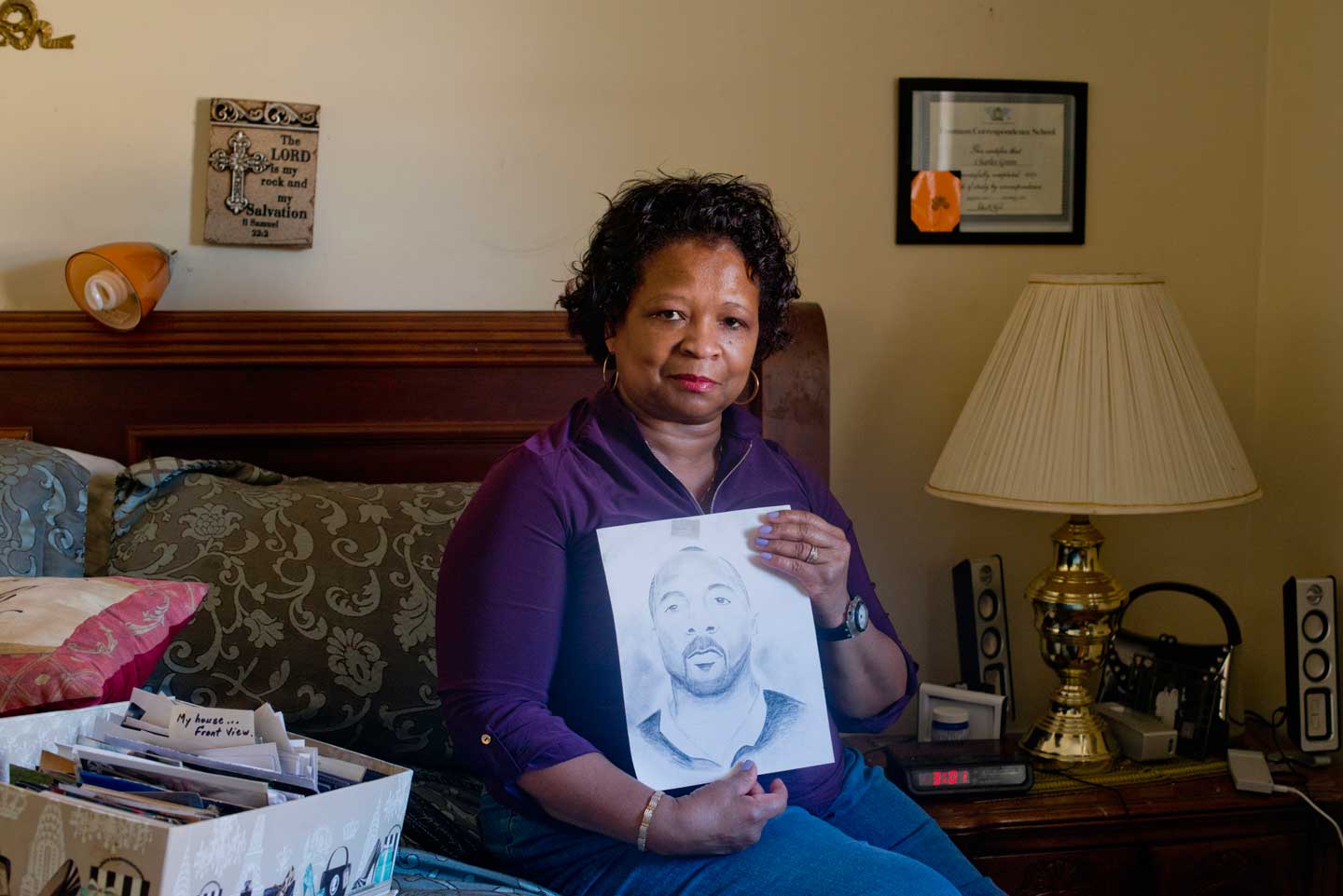

Keshawn’s mother, Linda Green, was pregnant and had a 9-year-old son when her husband Charles, then a construction worker, went to prison. She had no plans for a third child, but 14 years later, she learned that she and Charles were again expecting. “I was 40!” she says with a chuckle. As Linda struggled to stitch together her separated clan, family visits were the seam.

Linda Green, was pregnant and had a 9-year-old son when her husband Charles, then a construction worker, went to prison. Image: CAROLYN DRAKE/MAGNUM PHOTOS

Linda is a reserved woman. Just over five feet tall and with a bob haircut, she speaks slowly and deliberately. She met Charles at a movie theater in Jackson, and the two got married while still in high school. After he went to prison, Linda moved in with her mother and went back to school. “Between canteen, collect calls, and visiting, don’t ask me how much I’ve spent,” she says. “I know it’s enough to buy a car or a small house.” She peers over her eyeglasses as she searches through a box of photographs and pulls out one of her sons with their father. “It kept me looking forward to [the future],” she says of the extended visits. On holidays, Linda brought the ingredients to make traditional Southern Thanksgiving or Christmas dinners — turkey, dressing, greens, macaroni and cheese — as if the family were all at home. Other times, they would head outside to the picnic table and play a game of spades with other married couples. “It made the boys feel closer to Charles,” Linda recalls. “It wasn’t like they didn’t know their father — they made memories every visit.”

Keshawn remembers visiting as a toddler, hopping on his father’s back to go for a walk, or standing in front of a stately tree picking pecans. As a boy, alongside his older brothers, he kneeled in front of the big lake on the prison grounds as his father showed him how to hook bait onto his fishing pole. “I ain’t never know how — I was young,” Keshawn says with a Southern twang, twisting his coiled locks of hair around his fingers. He looks at his mother on the other couch. “My momma ain’t never showed me how to skin one.” She interjects, laughing: “Naw, because I don’t do that.” Some thing were a father’s duty. Green says his father, who’s a big sports fan, often challenged him to a game of basketball during their visits. “I got better,” he says. “At first, I couldn’t dunk or beat him, but then I started beating him.”

Ann Adalist-Estrin, who directs the National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated at Rutgers University, says extended visits are the most helpful developmentally for kids. They allow kids the opportunity to see their parents as real and human and take away the strain of making each visit perfect. “During regular visits, kids are monitored seriously,” she explains. “They’re in very uncomfortable visiting arrangements, with hard seats, limited time face to face, can’t touch each other. It limits the child’s ability to go through cadence.”

“Cadence” refers to the series of group developmental stages that some therapists have dubbed “form, storm, norm, and perform.” Initially, the child is elated to see his or her parent. But during longer visits, there’s greater room for upheaval: Kids feel comfortable broaching difficult topics involving sadness or anger, because there’s more time to recover and return to normal. “In a short visit, if kids are beginning to ‘form’ and ‘norm’ the relationship, they will not do the ‘storm’ part, because they don’t feel comfortable,” Adalist-Estrin says. “They don’t have the time to resolve it before they leave.”

Linda Green agrees. “[Charles and I] fussed a little bit,” she admits. “It showed Keshawn how a couple could be.” Her son had a chance to see firsthand that love and commitment are complicated.

Today, Keshawn lives with his mom in a terra-cotta brick single-family home in Jackson with a sprawling, manicured lawn. Around the time he turned 16, his “family house” trips died down. They were getting boring for him; no teenager wants to be stuck at home with his parents for a week. Keshawn started working and establishing his own independence. He feels that he finally achieved it “when I stopped asking my mom for money or rides.” Still, he continued to speak with his father by phone and visited him twice a month, building on the bond they created in family house and forging a connection that prompted him to heed his father’s advice from a distance.

“I still view Keshawn as a baby,” Charles says. “He thinks he’s grown, but at 20 he still don’t know nothing. We have talked about safe sex, girlfriends, staying in school, and becoming a man.” The conversations that Charles had with his son years ago in family house are continuing and deepening. The Greens both recall Keshawn having several girlfriends. “He brought a few of them around here to meet me,” Linda says, “but this last one met the mark, and Keshawn said he was going to introduce her to Charles. That was a big deal for him.”

First, Keshawn let his girlfriend speak to his dad on the phone, and later she put in an application to visit. “He’d never brought a girl to meet me,” Charles says. “I’d been telling them how to get along over the phone for a while, but that visit was real important.” It was more than a phone call, more than a picture. “You could see that she cared a lot about him,” Charles continues. “Keshawn wanted to play Mr. Tough Guy in front of me, but I knew she was the one for him.” During their visit, he recalls the two talking about money. “The young lady said, ‘Keshawn, your money is our money, and my money is our money. We split everything 50/50.’” Charles told his son that if they decided on a partnership, this was indeed the way it should go. “She’s good for him,” Charles says happily. “I’m not going to choose who he’s going to love, but I’ll guide him to make smart choices.”

Amari Phillips can’t articulate her feelings about her relationship with her dad yet. She knows he’s in prison, but she doesn’t comprehend it. In a soft voice, she tells me that he has a “trailer house,” and that she’s “sad” and “mad” that they won’t be able to play in it together anymore. But she doesn’t understand why.

- Corrections policies focus on the 2.2 million adults behind bars, not the 2.7 million kids who lose their parent.

Briana Olsem Winter, 11, who visited her mother in family house, understands more. She says the state’s decision to stop allowing visits from families is “just wrong.” When children can’t see their parents, “they won’t know ’em,” she says, looking down at the concrete.

Briana’s mother, Cristina Winter Pierre, 29, was once among the 7 percent of prisoners in Mississippi who are women. She says family house allowed her to be a mother and gave her daughter comfort. During regular contact visits, “you can’t hug on them like you would want to. And you really just can’t talk, because you got everybody in your business.” Pierre, who lost custody of four of her five children when she went to prison, says family house saved her relationship with Briana, her eldest daughter. “She would probably not know me,” she says, looking at Briana. “When you have that big of a space between you and your children for all them years, they do forget, if they’re young. And everybody says they don’t, but yes, they do, because my other children have no clue who I am.”

In June 2013, Sesame Street’s Sesame workshop launched the initiative Little Children, Big Challenges: Incarceration, which offers a number of free multimedia resources for families with young children affected by a parent’s imprisonment. Most notable among them was the introduction of Alex, a blue-haired, green-nosed Muppet, whose eyes are shaded by a gray hoodie. Like Amari, Alex has a father in prison. In a typical scene, Alex and two other Muppets are admiring toy cars, when one of them suggests asking their dads to help them build similar cars so they can all race together. “I don’t think so,” Alex mutters. “Oh, come on,” his friends insist. “It’ll be fun.” These simple words send Alex reeling. “He can’t do it,” says Alex, with his head bowed. “He’s not around right now.” They ask if he’s visiting a friend or on vacation. Alex just says his dad is “somewhere else.” Finally, he gives up, saying, “I don’t want to talk about it,” and then retreats to a stoop. Later in the scene, Alex admits he doesn’t want people to know that his dad is in prison or that he broke the law. This allows Sofia, the adult character, to teach the Muppets about incarceration and shame.

When I first meet Amari and her mom, they arrive as I’m ending my interview with Xacey Willis, 8, and her mother. Immediately, the gregarious Xacey directs her doe eyes at Amari and smiles widely. She runs over to her, offers some of her Funyuns, and asks her name. After the girls share that they both have a dad in prison — something they don’t reveal to classmates — they become inseparable for the next two hours. They sit next to each other at the table, laughing and coloring together, playing hand games, and finally striking a pose for my camera. Xacey, who pretends Amari is her younger sister, always takes the lead.

Xacey is a young prison activist. She wears a T-shirt with prisoners’ faces on it — her father’s included — and will quickly tell you that she’s “fighting for civil rights” and for her uncles and father to get out of prison. However, she keeps her dad’s incarceration a secret at school: “No, I don’t tell [my classmates]. I just tell them that he at work. I don’t like to tell them about my family a lot.” Xacey says she has a cousin in her classroom. Her usual booming voice drops to a whisper as she explains, “Her dad’s in prison too, but she don’t won’t nobody to know that. She think people gonna make fun of her.” Adopting a singsong voice and wagging her finger, she mimics the dreaded taunt: “Na-na-na-na-na-naah, your dad’s in prison, your dad’s in prison.”

Unfortunately, Amari and Xacey have never seen Alex; the character doesn’t appear on PBS. Rather, Sesame Workshop distributes the kits through criminal-justice groups, social workers, after-school programs, and state corrections departments. Part of a patchwork of nonprofit efforts to help kids with incarcerated parents, community programs are the only such resources available in Mississippi: There are no state-funded programs that focus on parental incarceration.

In 2012, the White House created a federal interagency working group, Children of Incarcerated Parents, to evaluate the federal programs and policies that impact these children. COIP is conducting research and running public-education initiatives, but federally funded programs to aid children like Amari and Xacey directly are hard to find. Though the Justice Department awarded $53 million in grants to reduce recidivism in 2015, just three grants, totaling a little more than $1.2 million, were committed to programs dealing explicitly with children of incarcerated parents. Of the three grantees, which run programs that focus on counseling and mentoring, only one has some aspect of assistance for visitation. Meanwhile, the Administration for Children and Families has no grants available for serving kids with parents in prison.

“There is so much more focus nowadays on the incarcerated individual, rather than also considering the impact that an individual’s incarceration may have on those he or she touches in his or her community or family life,” says Jeanette Betancourt, Sesame Workshop’s senior vice president for community and family engagement. Several studies that show a correlation between regular inmate visitation and reduced recidivism also indicate a link between prison visits and family bonding. The New York State Department of Correctional Services recognizes these findings, describing its Family Reunion Program as an effort to “preserve and strengthen family ties that have been disrupted as a result of incarceration.” But in general, corrections policies are focused on the 2.2 million adults who are currently locked up in federal and state institutions, not the 2.7 million children who have been cut off from access to a parent.

“I also think racism enters into it,” says Adalist-Estrin, who is also a child and family therapist. “We’re talking about disproportionate numbers of people of color. It’s easier to say we don’t want to give them that privilege, we don’t want them having children.”

- Tracey Chandler, whose husband is serving life in prison: “Everybody needs a hug. I know I do.”

I know I wasn’t better off without my father. Children are forgiving; they recognize human error. My father explained his crime, his imprisonment, and the necessity of his punishment, and I was grateful for the opportunity to exist somewhat wholly with my family. In fact, it wasn’t the barbed-wire gates or the officer holding a rifle in the gun tower that frightened me as a child. The frightening part was my father’s inability to step past a painted red line on the floor during regular contact visits or, worse, my own fear of touching him. Once, I watched his eyes well up as we mourned the death of my eldest brother, and I broke the rules and laid my hand on his. Most frightening of all, though, was the vitriol I saw in the eyes of the corrections officers, the belittling way they spoke to the prisoners and to us, their families. What was terrifying — and cutting — was that my dad was not perceived as human.

No one ever gave me permission to wear this uncomfortable truth. In most cases, our families live in the shadows, until we refuse to do so any longer. For Keshawn, that moment came in high school, when he realized that lying about his life wasn’t going to change it and that he didn’t care what people thought. “It got to a point when I stopped lying and told the truth,” he shrugs.

After family visits were taken away in Mississippi, conjugal visits were ended too. “We go in there to hold one another, hug one another, lift each other’s spirit,” says Angela Daniels, of Mississippi Advocates for Prisoners, whose husband is serving 40 years for attempted armed robbery. She thinks the view that conjugal visits are all about sex devalues the human need for privacy. “It’s not about just fulfilling the flesh,” she says. “We’re creating emotional stability. A man is not going to cry in front of others. Some will, but most won’t. We’ve taken our private time to share with one another, share our experiences, cry with one another. I was able to go in and relieve myself through tears and through prayer together in private.”

Xacey’s mom, Tracey Chandler, started the group Mississippi Southern Belles to support prisoners and their families. Her husband is serving life in prison, and she says that conjugal visits, which often happen as a part of regular day visits, helped maintain her family’s cohesion. On those occasions, her husband, who also has a 17-year-old daughter from a previous relationship, would share his own pain. “He missed Xacey’s first day of kindergarten, and my stepdaughter is going to graduate high school in May. He talks about missing all the important things in his children’s lives.” Chandler was able to comfort him: “Everybody needs a hug. I know I do.”

On a warm, sunny afternoon in late April, about 25 demonstrators gather on the steps outside the federal courthouse in Jackson to protest prison conditions, corruption, and visiting limitations. Among them is Linda Green, coming from her graveyard shift at work. She’s wearing a Mississippi Advocates for Prisoners T-shirt and holding a sign that reads Pro-Conjugal. It wasn’t until a few days later that Green realized the significance of the sign. “I’m such a private person,” she says. “It’s going to be some people asking, ’Why was she protesting for inmates? She must have someone in prison.’” Green participates in a prison ministry and recently gave a talk about the impact of incarceration on her family, but a TV appearance is a different level of publicity. “Charles said a lot of the inmates saw it,” she adds with a chuckle. “He was happy and proud of me. It made me feel good knowing I could be a voice for him on the outside.” She also feels that she doesn’t have a choice: “We’ve got to do this,” she offers.

As Keshawn thinks about the time his brothers served, he realizes that he was one of the lucky ones: He made it. Having a connection with your father is vital for every child, he says. He imagines that kids growing up now with a parent, but without extended family visits, will intensely feel the sting of their separation. Even with family house, it was hard for him. On the worst days, he felt so alone, he says: “No brothers, no dad. Me… just me. One person.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations. The photos were made possible by support from the Puffin Foundation.