Special Agent Gus Gonzalez leaned back in the front seat of his truck to get a better angle with his camera. It was December 5, 2011, a chilly day for a stakeout in subtropical South Texas. He’d been waiting for hours in the parking lot of an Academy sporting goods store in Brownsville. A few miles away, across the river in Mexico, a war over drugs and money raged. U.S. residents, paid by the cartels, were supplying most of the guns and ammunition.

Gonzalez and his partner, both agents with a federal law enforcement division called Homeland Security Investigations, had gotten a tip that two men they had been investigating would be buying bulk ammunition that day at the store, so they had staked out the parking lot to take photos and gather evidence. The day dragged on and the suspects still hadn’t shown. But now, Gonzalez couldn’t believe what he was seeing through the viewfinder of his camera. It was Manny Peña, a career U.S. Customs inspector. Back in Gonzalez’s days at U.S. Customs, he had worked side by side with Peña at one of Brownsville’s international bridges. He watched as the stocky 38-year-old with close-cropped hair rolled a shopping cart over to a white Chevy truck, then dropped a new Remington rifle into the bed and walked away. It didn’t look right.

“I think Manny just made a straw purchase,” he radioed to another agent. Suddenly, Peña turned and started walking toward him. Peña’s car, it turned out, was parked just a few spots away. Gonzalez ducked down in his seat. As Peña pulled out of the parking lot, Gonzalez skimmed through his photos, caught the white Chevy’s license plate number and called it in.

Gonzalez’s chance encounter with Peña at the sporting goods store would eventually cost the longtime customs inspector his job. The irony was that Peña had been caught by an agency that wasn’t even investigating him. In the previous two years, at least three other federal law enforcement agencies had opened investigations into Peña, who was an employee of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

A Border Patrol checkpoint along U.S. 77 near Sarita.Image: KIRSTEN LUCE

CBP’s internal affairs office had built a file on Peña with allegations that included displaying a “lack of candor” — federal law enforcement parlance for not fully disclosing the truth — and for “harbor[ing] a UDA,” an undocumented alien, who happened to be his wife, a Mexican citizen. A CBP disciplinary board had initially recommended firing Peña because of the findings, but his punishment was later reduced to a 14-day work suspension, which he finished three months before he was spotted at Academy.

Another investigation, opened in 2010, involved accusations far more serious. According to records obtained by the Observer, a task force led by the FBI amassed evidence that Peña was “conspiring” with other customs officers to smuggle drugs and people across the border. The FBI task force “conducted several [redacted] operations,” during which Peña was seen meeting with “a known Gulf cartel member,” according to a summary of the investigation. In court, prosecutors later described “numerous incidents” at the international bridge in which Peña “allow[ed] people to go through without being properly checked.” For such serious charges, Peña might have gone to prison for a long time. But by stumbling into the gun-running sting, he handed prosecutors a more expedient case to take to trial, which they did in July 2012. He never answered for the alleged corruption, only for lying about the gun purchase. Despite Peña’s protests that the rifle was a communal purchase to be shared with his hunting buddies, he was convicted, sentenced to five years’ probation and fired. Peña declined to comment for this story.

It was just dumb luck that after 12 years on the job, Peña was brought down by officers who weren’t even looking for him.

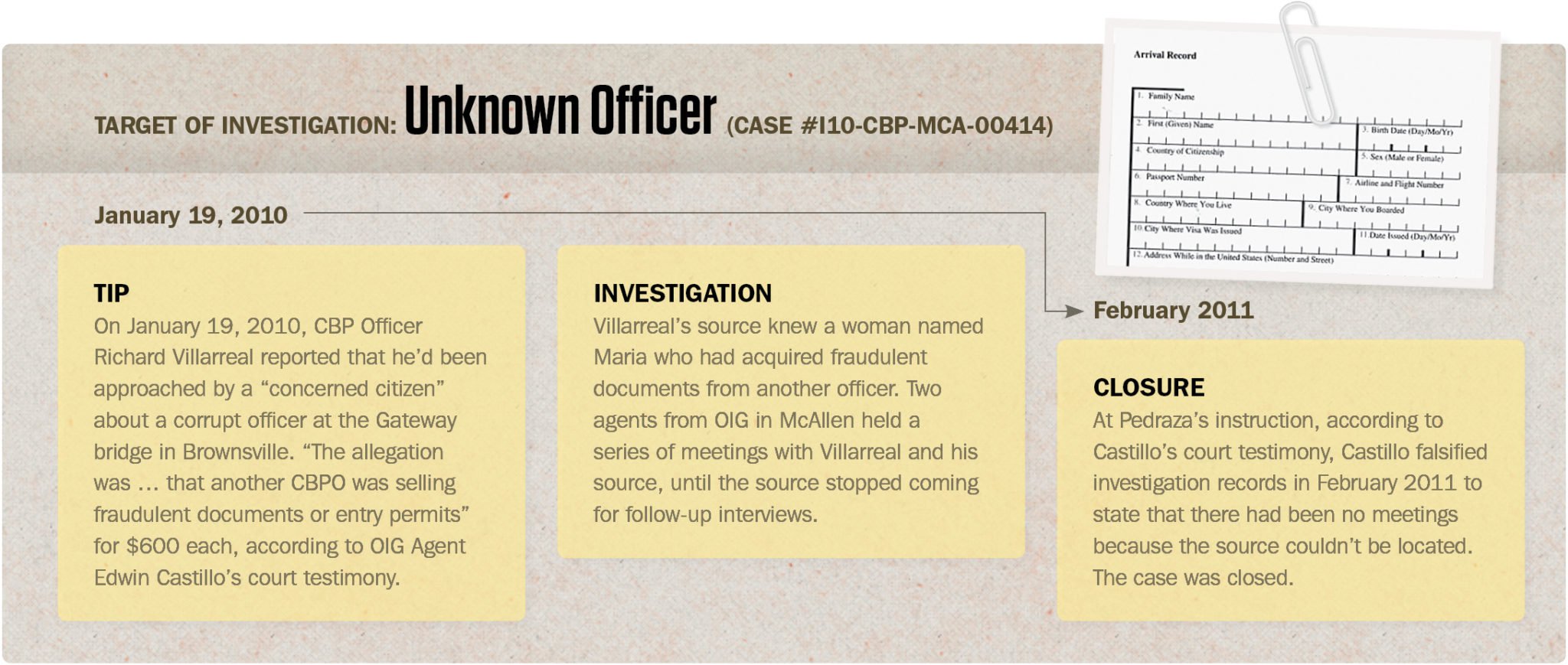

Why was he allowed to work under a cloud of suspicion for so long? The answer lies within the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General (OIG), which sounds like one more obscure corner of federal bureaucracy, but is the agency ultimately responsible for investigating corrupt and abusive agents. OIG opened a case on Peña in March 2010. But officials there mishandled the case so spectacularly — first by failing to investigate, then by lying about the work they’d done, and finally by trying to cover up their lies — that they became FBI targets themselves. As unwittingly as he’d stumbled into that stakeout in the parking lot, Peña also became part of a much larger investigation. Though the probe barely made headlines outside Texas, it would draw congressional scrutiny and expose the deep dysfunction within Homeland Security’s internal affairs apparatus, put high-ranking federal agents in prison, and implicate top Homeland Security leadership in Washington, D.C.

Image: CHAD TOMLINSON

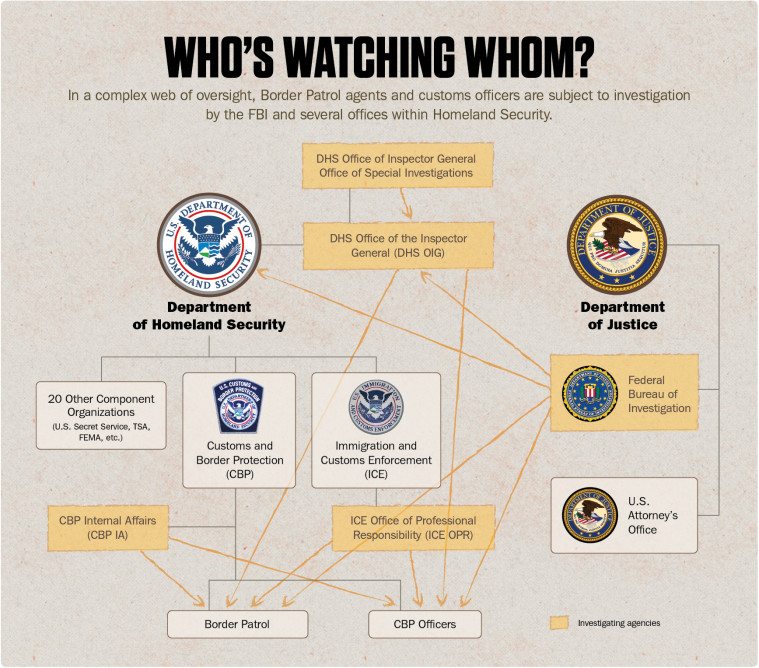

Many of the problems within the Department of Homeland Security and its internal affairs divisions can be traced back to its creation in the wake of 9/11. In 2002, the Bush administration and Congress rolled 22 agencies into one mega-bureaucracy. The U.S. Customs Service, for which Peña worked, was merged with the Border Patrol to become U.S. Customs and Border Protection. In his 2002 speech announcing the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, President George W. Bush promised that the new agency would “unite essential agencies that must work more closely together. … By ending duplication and overlap, we will spend less on overhead, and more on protecting America.” It didn’t quite work out that way.

The shakeup gave rise to a complex web of internal affairs bodies, with overlapping jurisdictions, conflicting interests and chronic funding shortages. In the shuffle, Customs and Border Protection — now the largest law enforcement agency in the country — was left without its own internal affairs investigators. That task would instead be left to OIG, which had roughly 200 investigators and responsibility for the oversight of more than 220,000 employees. (In comparison, the FBI has 250 internal affairs investigators for its 13,000 agents.)

Instead of streamlining investigations within DHS and rooting out corruption, OIG became known for hoarding cases and then leaving them uninvestigated — a black hole of bureaucracy. To make matters worse, the office often refused offers of help from the FBI and other law enforcement agencies that also keep watch over customs officers and Border Patrol agents. In the last two years, new leaders in DHS have pushed OIG to cooperate more with sister agencies, but dysfunction still runs deep. Each agency has its own protocols, case numbers and filing systems, its own sense of institutional pride, and its own acronyms. The FBI, DHS OIG, ICE OPR (Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of Public Responsibility) and CBP IA all run their own competing investigations — even though, with the exception of the FBI, they’re all part of the Department of Homeland Security.

Meanwhile, the Border Patrol’s ranks keep growing. Congress is intent on “more boots on the ground,” but pays little attention to the men and women tasked with keeping border agents accountable. Accounts of corruption have multiplied: In Arizona, a Border Patrol agent was caught on police video loading a bale of marijuana into his patrol vehicle; another agent in Texas was caught waving loads of drugs through the international port of entry for a cartel; and in California, a Border Patrol agent smuggled immigrants across the border for money. But Homeland Security officials have no way to gauge how extensive the problem is within its ranks. “The true levels of corruption within CBP are not known,” concluded a Homeland Security advisory panel of law enforcement officials in a 2014 report. The corruption investigations conducted by OIG, the panel noted, are often unsatisfactory. “These investigations are nearly all reactive and do not use proactive risk analysis to identify potential corruption. Moreover, they often take far too long.” This means that agents like Manny Peña, suspected of ties to drug cartels, can stay on the job for years, waving people across the border.

The dysfunction has put the fundamental mission of DHS in jeopardy. After all, what good are more boots on the ground if the men and women wearing them also work for the cartels? What benefit is an 18-foot wall when criminals can bribe their way through the gate?

In January 2011, Eugenio “Gene” Pedraza was special agent in charge at OIG in McAllen, with authority over a dozen internal affairs investigators. Pedraza and his team were responsible for policing fraud, waste and abuse among several thousand border and customs agents ranging over 200 miles from Brownsville to Laredo. On paper, Pedraza, 49, was a seasoned professional with a long career that included a stint at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Inspector General and nine years as a Border Patrol agent.

Image: BRIAN STAUFFER

But by the time Pedraza hired Special Agent Robert Vargas that January, the McAllen office had become a frustrating place to work, plagued by low morale and high turnover. The agents who worked there would later describe the office as “hostile,” “rough” and “dreadful.” Pedraza, they said, would “hold things against you and … make your life miserable if you didn’t go by what he wanted.” Pedraza’s policy was to open a case on any tip the office received. The result, Vargas later testified in court, was “a large caseload. We had more cases than we could deal with.”

The Manny Peña case was among the first Vargas was given to investigate. But when he glanced inside the case file, it was basically empty. It contained the initial tip about Peña that had sparked the case in March 2010 — then nothing. So he got to work.

Image: CHAD TOMLINSON

Vargas had years of investigative experience with the U.S. Air Force and the Harlingen Police Department, where he had worked on a federal anti-drug task force. He knew a good case when he saw one. Some are all fat — anonymous tips about anonymous agents. But Manny Peña? “That was a case we considered meat,” he later testified. Vargas began by following some basic leads, staking out Peña’s home and running background checks on his family and friends, typical first steps that hadn’t been taken since the case was opened more than a year earlier.

Vargas learned about an FBI task force looking into Peña, and that the agents had a confidential informant who’d been feeding them information. Vargas reached out to see if the FBI would connect him with the informant, but what he got instead was a lesson in the anti-corruption world’s pecking order.

“Our office was known as the black sheep of the internal affairs community,” Vargas later explained to government lawyers, “so we couldn’t get any assistance from the FBI.” The FBI had been around for more than a century and was well versed in its investigative role, but Vargas belonged to a small internal affairs office still trying to figure out where it fit among a patchwork of border law enforcement agencies. It was a dead end.

Then something else unexpected happened. Pedraza told Vargas and the other agents that inspectors from a sub-office within OIG called the Office of Special Investigations were coming from Washington, for the first time in years, to audit his files and gauge “office spirit.”

Image: BRIAN STAUFFER

On the morning of August 31, 2011, a couple of weeks before the impending inspection, Pedraza summoned Vargas to a conference room. On the conference table, Pedraza had placed four or five files — the master copies of the cases he had assigned Vargas. He pointed to the file on Peña and explained that it was one of the cases he planned on giving to the inspectors from Washington. Inexplicably, DHS policy allowed Pedraza to handpick the cases the inspectors would review. (According to OIG officials, that policy has since changed to let the inspectors, not station chiefs, choose the cases.) A 15-month gap in Pena’s file between any investigative work wouldn’t look good, Pedraza explained. “We need to clean this case up,” Vargas later recalled Pedraza telling him. “Fill in the gaps.” In other words, make it look like someone in the office had been investigating Peña all along.

Vargas didn’t like it, but he wanted to keep his job. He’d been moving his family all over the country for years — he’d even left his wife behind for an assignment in Korea — and now they’d finally settled down. His new salary was well beyond what he’d made as a Harlingen cop. After Pedraza left the room, Vargas corralled his partner and walked two blocks to the Subway in the McAllen bus terminal. In the sandwich shop they talked the problem through: Pedraza was out of his mind, no way could Vargas fake the work on Peña’s case. But Vargas was a new agent, still on probation. How could he say no? The two settled on a plan to go back to the office and plead their case to Wayne Ball, the senior agent who’d plucked Vargas from the Harlingen Police Department and recommended him for the job.

Vargas walked into Ball’s office and made his case. The fake investigative work might fool the inspectors from Washington, but if any of the agents were asked to testify, it would never hold up in court. By faking the records, he would sabotage the case against Peña. Vargas pleaded with Ball, saying, “We cannot be doing this.” But the answer from Ball was brief: “Fuck you. Just do it.”

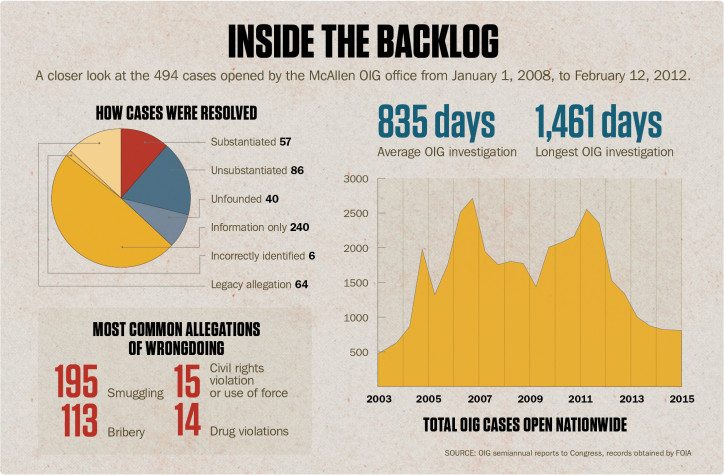

If the DHS investigators weren’t working meaty cases such as Peña’s, what were they doing? To get an idea, the Observer requested, under the federal Freedom of Information Act, information on all the cases opened in the McAllen office when Pedraza was in charge, from January 2008 to February 2012. The result was a list of just fewer than 500 cases, more than 40 investigations for each agent. According to court testimony, each of the office’s 12 agents carried up to a dozen cases at a time — two or three times what was typical at the 30 other inspector general offices nationwide.

The result: a growing backlog of cases that took years to close, if they were investigated at all. They included use-of-force complaints related to shooting deaths, as well as smuggling, bribery and sexual abuse allegations. Of the cases in the McAllen office, 25 percent were listed as either “unsubstantiated” or “unfounded,” and 63 percent were closed with the vague designation of “legacy allegation” or “information only.”

A little more than 10 percent — 57 of the 494 cases the Observer reviewed — were “substantiated” by investigators. Of those, 10 were handled by “administrative” action, meaning the agent was probably fired or allowed to resign or retire, while the remaining 47 cases were referred to prosecutors. It’s unclear how many were ever taken to court.

Image: CHAD TOMLINSON

When investigators did take initiative on a case, it could go spectacularly awry. What happened to a confidential informant known as Norma, who worked with an OIG investigator on a human smuggling case in 2010, suggests that OIG’s dysfunction went beyond just neglect. (Norma asked that her full name not be used, since she fears repercussions due to her work as an informant.)

Norma, who is undocumented, worked as an informant for the DEA and other federal agencies for two decades with the hope that she’d be granted U.S. citizenship. In 2010, her handler at the DEA gave her the phone number of Rolando Gomez, an investigator from the McAllen OIG office. She was unfamiliar with OIG but hopeful that the agency would finally help her gain citizenship.

But Gomez told her he would only be able to provide a temporary work visa. Norma decided she was tired of putting her life in danger in exchange for a work permit, so she turned him down. A few days later, Gomez and three other agents showed up at her doorstep in a suburb of Dallas at 5 a.m. “It’s the police,” a voice said. Norma opened the door to a man holding a badge.

“I’m Rolando,” he said. “Can we come in?”

“Do I have a choice?” Norma asked.

“Not really,” he said, according to Norma. The men walked inside. It was just Norma and her 13-year-old daughter at home. They were still in their pajamas. One of the men locked Norma’s daughter in a bedroom, while the other three went through her home.

“He told me I was a criminal and that I had to help him,” Norma said. “He was either going to sign me up as an informant or have me deported.”

Norma, photographed at her home outside Dallas, spent years as an informant for federal law enforcement, but the arrangement fell apart shortly after her first contact with OIG.Image: PATRICK MICHELS

Her first assignment was to wear a wire and collect evidence on a customs agent who was allegedly smuggling immigrants across the Rio Grande near Brownsville. Norma went to the agent and asked if he’d smuggle someone across for her. “The guy was scared. He said, ‘We’re not doing anything right now.'” So Norma returned home. But eventually, Gomez’s superiors in Washington heard about the 5 a.m. visit to her home and how he’d forced her into working for OIG. They weren’t pleased.

Norma had become a problem for the McAllen office. In April 2011, the next time she visited the office, three agents, including Gomez, were waiting for her. “You’re a troublemaker and we can’t use you anymore,'” Gomez said, according to Norma.

In court, Gomez would describe the scene: “She was upset. … She said I tricked her into coming into the office.” That day, two agents drove Norma to an international bridge near McAllen on Pedraza’s orders, according to court documents. Pedraza instructed Gomez to falsify his report by writing that Gomez had personally driven her to the bridge. Pedraza said it wouldn’t look right that Gomez had made two other agents do it, when it was his responsibility.

Reynosa, just on the other side of the river, was riven by gun battles and drug-related killings. “They took me to the bridge and told me to start walking,” Norma said. “They stood watching until I’d crossed into Mexico.” Norma had been given no time to prepare or call her family. Now she was in one of the most dangerous regions of Mexico and had no one to back her up.

Unbeknownst to Vargas, the drama with Norma had played out just weeks before he’d started his new job at the McAllen office. Now he was caught up in his own private crisis. He sat at his desk and debated whether to lie and fabricate an investigation, as Pedraza had ordered, or refuse and lose his job. As he would later testify in court, Vargas wrote up his investigation of Peña so far — the stakeout, the database checks — but backdated the entries by a year or more, and credited the work to Wayne Ball. It would look like they’d been investigating the case all along. Vargas quit looking into Peña after that because, as he later explained, “The case was tainted.”

A few days later, the three inspectors arrived from Washington, D.C. Two of them busied themselves reviewing the records, while the third agent, James Izzard, took OIG personnel aside one by one to ask whether they were happy in the office. Vargas didn’t mention the Peña case during his interview. It wasn’t until that night, when Izzard called Vargas at home and asked point-blank whether Pedraza had ever given an order to falsify records, that Vargas came clean. Other agents also confessed to Izzard that they’d doctored cases at Pedraza’s instruction. Izzard returned to Washington armed with damning evidence against the station chief in one of the agency’s most critical field offices.

The agents in McAllen waited. They assumed the revelations would spell Pedraza’s end. But for weeks there was silence. It was almost stranger than being asked to falsify records in the first place. Vargas wondered whether anyone in Washington cared. Then one day he received an email from Izzard’s boss, John Ryan, an OIG special agent in charge, asking Vargas to call him. Vargas dialed the number.

He expected Ryan to be outraged, but instead, Vargas later testified, Ryan began probing him about Pedraza’s exact words. Had Pedraza ever used the word “fabricate?” Did he ever explicitly tell Vargas to “lie?” Perhaps Vargas had simply misunderstood? It was a puzzling phone call. The situation grew stranger when Ryan and his boss, Thomas Frost, the inspector general’s top investigator, visited McAllen to follow up on the agents’ complaints a few weeks later. After they flew back to Washington, Ryan wrote up an internal report in which Pedraza denied having told anyone to fabricate casework, and that seemed to put the issue to rest.

Vargas was stunned. “I gave it to my agency,” he later testified, “expected them to do the right thing, and they didn’t.”

Image: BRIAN STAUFFER

Days passed and Norma was stuck on the Mexican side of the border. Back in Texas, her four kids and husband were frantic. Eventually she managed to hire a smuggler and cross the Rio Grande into Texas. But once she was back home, she felt like her life was spiraling downward. She was afraid of Gomez and OIG, afraid they’d deport her to Mexico again, which could be a death sentence for an informant. Deeply depressed, not knowing where else to turn, she reached out to a Dallas real estate manager, Ralph Isenberg, who had started his own immigration advocacy group called the Isenberg Center for Immigration Empowerment, or ICIE. A fiery character, Isenberg is often quoted in the media blasting ICE and other federal agencies over their harsh treatment of immigrants.

Isenberg listened to her story for several hours. Was she making it all up? “I thought it was the wildest thing I’d ever heard,” he said. But then Norma produced her paperwork and other evidence. “I couldn’t believe the government had acted this way,” he said. Furious, Isenberg called Gomez. Then he called Pedraza to file a complaint. But he got nowhere, so he started hounding the FBI. An FBI agent came to Dallas to interview Isenberg and Norma about her story. Tipped off by a member of the inspector general’s office, and prodded by Isenberg, the FBI began to take a keen interest in Pedraza’s shop.

On January 25, 2012, Vargas had just finished a meeting in the FBI’s Brownsville office about a case unrelated to Norma’s when, to his surprise, one of the agents pulled him aside. Two FBI agents from San Antonio were waiting in another room, and wanted to speak with him. They walked in and told Vargas they knew about the falsified case records. They peppered him with questions about Pedraza and other higher-ups in the McAllen office.

Sitting face-to-face with the FBI, Vargas still clung to institutional loyalty. “I’m not going to sit here and tell you guys anything until I talk to my agency,” Vargas told the agents, and then he walked out of the room. That night, one of them called Vargas, pressuring him again to speak up. “I’d rather give my story to a grand jury,” Vargas told the agent.

He got his chance soon enough. In February 2012, OIG placed Pedraza on unpaid leave. A month later, his bosses in Washington, D.C., Ryan and Frost, were also put on leave by OIG while the Department of Justice and the FBI conducted their investigation into the agency. In the months that followed, agents from the McAllen office shuttled to courts in Washington and Brownsville to testify before federal grand juries. At least five agents were placed on paid leave by OIG for their part in falsifying records. In April 2013, Pedraza was indicted on multiple counts of falsifying records, obstructing an agency proceeding, obstruction of justice, and conspiracy. Agent Marco Rodriguez was also indicted for falsifying records, obstructing an agency proceeding, and conspiracy. Special Agent Wayne Ball had already pleaded guilty on one count of falsifying records and of obstructing an agency proceeding.

Another year passed before Pedraza went to trial. Meanwhile, at a time when a watchdog was most needed at Customs and Border Protection, almost no one was on hand in the McAllen office to investigate. Besides corruption, the number of fatal shootings along the border was on the rise. From 2010 to 2012, Border Patrol agents killed at least 22 people and injured several more, but the investigations went nowhere and agents went unpunished. Two especially egregious fatal shootings in 2012 in the Rio Grande Valley, involving unarmed men standing in Mexico, were under the direct purview of the McAllen OIG office. But details — if there are any — of the investigations and a resolution have never been released. (The problem is not limited to Texas. To date, only one Border Patrol agent has been indicted for fatally shooting an unarmed person in Mexico, and that was only in October, for a shooting in 2012.) Border residents were left to wonder whether Homeland Security had any internal control at all.

Maybe Pedraza’s trial would finally reveal the answers to the mounting questions about how DHS policed itself. In March 2014, inside the imposing brick federal courthouse in Brownsville, agents took the stand one by one. “I didn’t have it in me to tell [Pedraza] no,” Vargas confessed, and he wasn’t the only one. Pedraza had cornered a handful of other agents, showed them cases involving little or no work since they had been opened and told the agents to “bridge the gaps.” At least one agent refused to do it, but most played along. The cases they doctored, according to investigative records obtained by the Observer, included a customs officer accused of helping pregnant Mexican women get into the country to give birth, another officer suspected of selling permits for temporary legal status, and a Border Patrol agent allegedly working with a drug cartel to bring drugs and people into the United States. Many of the cases contained solid leads from agents who’d broken rank to tip off the agency about wrongdoing. Now they were dead ends: If a prosecutor ever took one to trial, the faked investigative work would be impossible to back up with testimony.

The specter of indictments for higher-ranking officials hung over Pedraza’s trial. Lawyers on both sides repeatedly mentioned a grand jury in Washington, D.C., that had convened to consider the role Pedraza’s boss, John Ryan, had played in the scandal and the report Ryan had drafted that seemed to absolve Pedraza. Significantly, the McAllen agents had all avoided prosecution by testifying against Pedraza, but if Pedraza had been offered a deal to testify against his bosses, he hadn’t taken it. Almost a year after Pedraza’s indictment, Ryan remained on leave, with pay, facing no charges.

Image: CHAD TOMLINSON

Agents on the witness stand offered a consistent and troubling narrative of Pedraza as a manipulative boss. That seemed clear enough. But the trial produced more questions than answers. From Pedraza on up, the motivations were puzzling. Prosecutors described Pedraza as panicked and insecure in the face of the looming inspection, afraid to have his incompetence exposed. But he had passed inspections before, so why break the law now? Why had he insisted on opening so many cases while his office was understaffed? And why, when told by multiple agents that the inspector general’s biggest office on the Texas border was torpedoing its cases, had OIG headquarters in Washington, D.C., not taken action before the FBI got involved? (Pedraza and his attorneys declined to comment to the Observer.)

At trial, both the prosecution and the defense characterized the backlog of cases as the result of bureaucratic snafus and Pedraza as a lazy supervisor who failed to do his paperwork, or made the mistake of filling in reports with the wrong dates. Taking Pedraza to trial meant opening a door to his office’s inner workings, but the prosecutors and Pedraza’s lawyer — a former U.S. attorney himself — seemed to open it only as much as necessary.

Before sentencing Pedraza, U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen seemed bothered by the question of how far up the chain of command the scandal reached. Hanen wondered aloud whether he was being used as a pawn, whether the Justice Department’s lawyers had shown him the whole picture.

“My concern,” Hanen told prosecutors, “is that [Pedraza] has been singled out and is somehow being prosecuted in a different fashion than everybody else.”

Hanen wanted to know what had become of the investigation into Ryan and Frost. A prosecutor assured Hanen that their cases were still pending, but the judge wanted specifics.

“I don’t get much comfort in ‘It’s still under investigation,'” he said. “I mean, you know, we’ve had matters under investigation for years, and nothing ever happens one way or the other. It just sits there and sits there and sits there.”

Hanen asked the Justice Department lawyers to guarantee that Pedraza wouldn’t be the fall guy for higher-ranking political appointees. “If something is illegal in McAllen or in Brownsville,” he said, “the same standard ought to apply in Washington, D.C.”

Image: BRIAN STAUFFER

The Department of Homeland Security headquarters in Washington is shrouded behind a thick tree line on the former grounds of St. Elizabeths Hospital, once known as the Government Hospital for the Insane. It took more than a decade for Congress, and Homeland Security’s own multiheaded leadership, to get the headquarters built.

In 2006, James Tomsheck, a former Secret Service official, was hired to lead CBP’s new internal affairs office. The tension between OIG and CBP over the backlog of cases had grown worse, and CBP had finally been given the authority to start its own internal affairs division. There was a catch, though. Their investigators could only handle administrative matters, not criminal cases such as corruption or excessive force. OIG would still get first right of refusal on those.

Tomsheck populated his staff with other trusted Secret Service veterans, and told theObserver that he soon had a clash of priorities with Border Patrol officials. He fought to create a universal polygraph program for new hires, which he says a surprising number of applicants failed. He began working with the FBI on border corruption cases, to help push them forward, even though the cases were also under the purview of OIG.

Former Customs and Border Protection Internal Affairs chief James Tomsheck says turf wars within the Department of Homeland Security hurt his efforts to root out corruption.

A low point came in 2009 when Frost, the high-ranking OIG official, sent a letter to Tomsheck demanding he quit working with the FBI and stop investigating anything until ordered to do so by higher-ups at DHS. Frost suggested that Tomsheck’s office was only sowing confusion by breaking the chain of command to help the FBI. Tomsheck said he was doing what he could at the time to help root out corruption. “OIG, who was taking virtually every case and refusing to accept assistance from others … was stockpiling cases,” Tomsheck said. “They lacked the resources to investigate anywhere near the number of cases that they were holding onto.”

Tomsheck’s superiors directed him more than once, he said, to keep corruption cases to a minimum. “It was very clear to me, after having several conversations with my colleagues and counterparts at the FBI, that DHS was attempting to hide corruption, and was attempting to control the number of arrests so as not to create a political liability for DHS,” he said.

James Wong, Tomsheck’s former deputy, recalled a committee formed by CBP leadership in 2009 to, as he put it, “redefine corruption” to include only border security issues such as bribery, smuggling and assisting cartels, and not offenses like sexual assault, physical abuse or misappropriating money. The leadership was apparently tired of having to answer to Congress for all the corruption cases. “What they wanted to do was present a better picture,” Wong said.

In 2012, as Pedraza, Ryan and Frost were investigated, DHS Inspector General Charles Edwards was summoned to Congress to explain why so many cases had been languishing for so long. Edwards was new to the job and had only been hired on an interim basis, but he hoped to be appointed permanently. In a hearing before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform on August 1, 2012, he told lawmakers that his office had 1,591 open cases on allegations of corruption, excessive use of force and other charges, which undoubtedly included some of the cases that had been sitting untouched in the McAllen field office. To clear the backlog, Edwards pledged to hand over nearly half of the cases to Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Office of Professional Responsibility — yet another internal affairs office within DHS — as well as to CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs.

Lawmakers asked Edwards questions similar to those that would be raised — and left unanswered — at Pedraza’s trial. Why had the backlog grown so large in the first place? Who was responsible for leaving so much alleged corruption uninvestigated? Edwards blamed it on a lack of investigators and an inefficient case referral system. During several hearings, Edwards promised that OIG finally had its troubles under control — a claim undercut by his resignation in December 2013 after a congressional investigation found that he had been using government resources to cover his personal travel and pay for his wife to work remotely from India. With a background in information technology, he also seemed to have little clue about how to manage criminal investigations.

A car is disassembled at the Port of Entry in San Ysidro, California, after drugs were found inside. As the busiest border crossing in the United States, Customs and Border Protection agents must screen effectively while not stifling cross-border commerce. Image: KIRSTEN LUCE

When reached at his home outside Washington, D.C., Edwards seemed to still be processing his tenure at OIG, trying to figure out where things had gone wrong. “It was a very toxic environment when I got in [there] and the inspector general before me kind of promoted that, and I wanted to change that,” he said. Edwards said he cared most about improving the system, not making a show of somebody’s failures. “I said, ‘You don’t have to wait for the report to be finished. Here are the things you can fix.’ That’s the approach that I took,” he said. “There were some cases that were older than five years, which was way too long,” he said. “The statute of limitations pretty much was running out.”

It’s still unclear what happened to those hundreds of unworked cases, whether any of them were ever fully investigated. Cases sent to ICE from the McAllen inspector general’s office were transferred on May 23, 2012, according to records the Observeracquired. In response to a request for all the cases transferred from the inspector general that month, the ICE Office of Professional Responsibility sent the Observer a list of 74 cases. None were listed as “substantiated.” Few were “unsubstantiated” either. Most were simply closed without explanation. Edwards said he couldn’t recall whether any of those transferred cases ever resulted in a prosecution. He did recall some cases being transferred back to OIG, per agency policy, after another internal affairs office found evidence of criminal behavior.

- Potentially corrupt DHS agents have remained employed for years.

Wong said OIG was dangerously disorganized. “They were just not standardized enough,” he said, and the result was hundreds of cases with no clear resolution. “If you have an allegation, you should come up with one of the following resolutions: substantiated, unsubstantiated,” Wong said. “It should be one or the other.” But officials’ insistence on asserting OIG’s “primacy” kept anyone else from uncovering the truth. “By holding all the cases, essentially they were only able to service the tip of the iceberg, and everything else just laid below the surface.”

Tomsheck said the case pileup was just a symptom of the lack of interest, at the highest levels of Homeland Security, in exposing corruption. Edwards was intent at the time on pleasing then-DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano, and there was no political benefit in highlighting problems within the agency, Tomsheck said. “He was very clearly not the watchdog of DHS but the lapdog for the secretary’s office,” Tomsheck said of Edwards. “The release date of audits was in many instances set not by the inspector general’s office but by the secretary’s office to accommodate political agendas.”

Image: CHAD TOMLINSON

When reached in Washington, D.C., John Sandweg, former acting general counsel for Napolitano, called Tomsheck’s allegations “utterly ridiculous.” He said, “The secretary was incredibly committed to fighting corruption and constantly looking at new ways to enhance the department’s efforts to minimize corruption within the agency.”

Tomsheck can now speak publicly about his problems with CBP because he doesn’t have a career to protect anymore. In June 2014, he was removed from his post as head of internal affairs in what was widely seen as a signal that CBP was cleaning house in response, in part, to a scathing report detailing unchecked abuse by CBP officers. Tomsheck was reassigned to a new job within the Border Patrol. An FBI agent named Mark Morgan was brought in to replace him. Tomsheck has since retired and is involved in legal proceedings with DHS over his removal. He has applied for whistleblower status and is fighting to rehabilitate his reputation.

Edwards also denied Tomsheck’s claims that politics affected his actions while inspector general at DHS. “There was not a single instance where there was any pressure from the secretary asking me to do anything or from further up in the White House,” he said. But his firing, he said, was a political act, a fit of congressional grandstanding that cut short a decades-long career just as he was beginning to clean up the office.

Gene Pedraza is nearly a year into his three-year sentence at a federal prison in Louisiana. Wayne Ball received a lighter sentence — he’s due to be released from prison in January. The government dropped its charges against Marco Rodriguez. After almost two years of administrative leave with pay, Gomez, Vargas, Rodriguez and the other agents in McAllen were recently reinstated and are back at work at OIG. And what about the other officials in Washington, D.C., who were under grand jury investigation? A Justice Department spokesman wouldn’t say whether there’s currently an open investigation into John Ryan or Thomas Frost. Frost, Ryan and the OIG public affairs office did not respond to requests for comment. Frost is now a high-ranking official in the inspector general’s office for the U.S. Postal Service. John Ryan is still listed in the staff directory as a special agent in charge at OIG. After Charles Edwards was fired for misappropriating funds and other ethical lapses during his stint as inspector general, he found another job at DHS in its Office of Science and Technology. He was finally forced to leave the agency in July after repeated pressure from Congress.

In 2014, Jeh Johnson, the new DHS secretary, finally did what each of his predecessors refused to do and gave internal affairs at Customs and Border Protection the authority to run its own criminal investigations. But the law enforcement advisory panel he recently created, which includes New York City police commissioner William Bratton and former DEA head Karen Tandy, has said he’ll need to more than double the number of investigators at CBP, from 207 to 550. “This needs to be rectified as expeditiously as possible,” the panel urged. “True levels of corruption” are not known within the agency, the panel noted. “This means that pockets of corruption could fester … potentially for years.”

But if history offers any lessons about the Department of Homeland Security, it’s that change won’t come quickly or easily. Whether DHS can clean house and finally tackle corruption will depend a great deal on Congress and whether it supports reform. At least 120 congressional committees, subcommittees and task forces have oversight of DHS — all of them vying for influence over the nation’s third-largest federal agency. Meanwhile, the beleaguered DHS internal affairs offices will have plenty of work in the coming years: In October, the Border Patrol announced plans to hire 3,000 more agents, its largest hiring initiative in a decade.

Gene Pedraza, former station chief of the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General's McAllen field office, leaves the federal courthouse in Brownsville with his wife and legal team, following his sentencing on December 15, 2014. Image: PATRICK MICHELS

At the Texas border, Norma has seen a lot of agents come and go. As a drug smuggler and a confidential informant, she’s worked both sides of the line. She’s seen her share of corruption. In her view, the more “boots on the ground,” the bigger the pool of potential candidates for the drug cartels. “Corruption is part of the business model,” she said. “It’s really true what they say: Money talks. Oh, you show someone some money and they’re going to be in. I don’t care who it is. That’s never going to change.”

What has changed is Norma’s view of law enforcement after her experience working with those who are supposed to police the police. She never thought she’d be afraid of the “good guys,” she said. “I thought they were by the book. I thought I was the criminal and I was obligated to help them because I was the bad person,” she said. “I had no idea.”

This story was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations, where Melissa del Bosque is a reporting fellow.