This story has been edited and condensed. You can read the full story and explore the data at McClatchy DC.

JACKSON, SC—

Byron Vaigneur watched as a brownish sludge containing plutonium broke through the wall of his office on Oct. 3, 1975, and began puddling four feet from his desk at the Savannah River nuclear weapons plant in South Carolina.

The radiation from the plutonium likely started attacking his body instantly. He’d later develop breast cancer and, as a result of his other work as a health inspector at the plant, he’d also contract chronic beryllium disease, a debilitating respiratory condition that can be fatal.

“I knew we were in one helluva damn mess,” said Vaigneur, now 84, who had a mastectomy to cut out the cancer from his left breast and now is on oxygen, unable to walk more than 100 feet on many days. He says he’s ready to die and has already decided to donate his body to science, hoping it will help others who’ve been exposed to radiation.

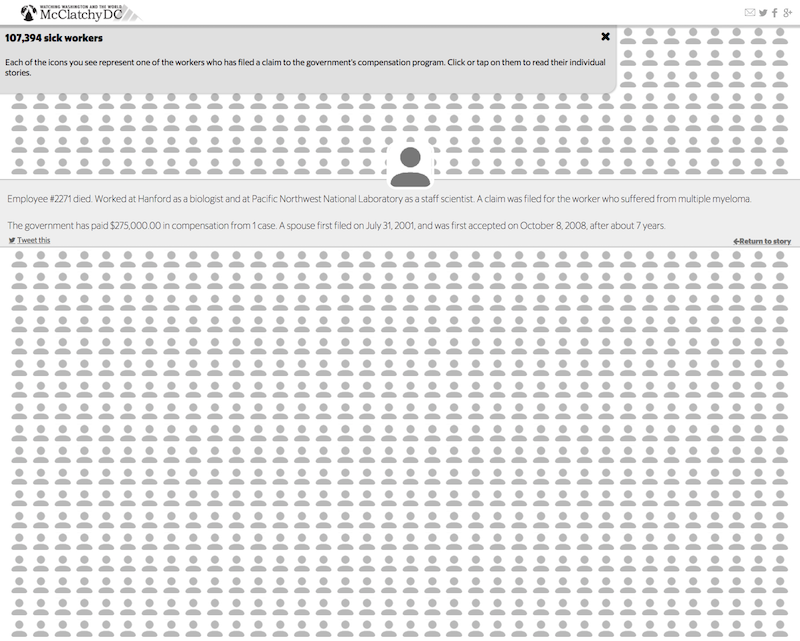

Vaigneur is one of 107,394 Americans who have been diagnosed with cancers and other diseases after building the nation’s nuclear stockpile over the last seven decades. For his troubles, he got $350,000 from the federal government in 2009.

Byron Vaigneur.Image: Gerry Melendez/McClatchy.

His cash came from a special fund created in 2001 to compensate those sickened in the construction of America’s nuclear arsenal. The program was touted as a way of repaying those who helped end the fight with the Japanese and persevere in the Cold War that followed.

Most Americans regard their work as a heroic, patriotic endeavor. But the government has never fully disclosed the enormous human cost. Now with the country embarking on an ambitious plan to modernize its nuclear weapons, current workers fear that the government and its contractors have not learned the lessons of the past.

For the last year, McClatchy journalists conducted more than 100 interviews across the country and analyzed more than 70 million records in a federal database obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. Among the findings:

— McClatchy can report for the first time that the great push to win the Cold War has left a legacy of death on American soil: At least 33,480 former nuclear workers who received compensation are dead. The death toll is more than four times the number of American casualties in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

— Federal officials greatly underestimated how sick the U.S. nuclear workforce would become. At first, the government predicted the program would serve only 3,000 people at an annual cost of $120 million. Fourteen years later, taxpayers have spent sevenfold that estimate, $12 billion, on payouts and medical expenses for more than 53,000 workers.

Image: MCCLATCHY DC

Click here to explore the data.

— Even with the ballooning costs, less than half of those who’ve applied have received any money. Workers complain that they’re often left in bureaucratic limbo, flummoxed by who gets payments, frustrated by long wait times and overwhelmed by paperwork.

— Despite the cancers and other illnesses among nuclear workers, the government wants to save money by slashing current employees’ health plans, retirement benefits and sick leave.

— Stronger safety standards have not stopped accidents or day-to-day radiation exposure. More than 186,000 workers have been exposed since 2001, all but ensuring a new generation of claimants. And to date, the government has paid $11 million to 118 workers who only began working at nuclear weapons facilities after 2001.

The silent deaths

Without question, the the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act has left a mark, providing average compensation payments of $119,102 to 49,934 former workers across the country.

But while the US Department of Labor, which administers the compensation program, makes routine reports on how much it spends and how many people it serves, it has been silent on the number of workers who have died.

That’s by design.

Amanda McClure, a Labor Department spokeswoman, said the department’s job is to adjudicate claims and to determine eligibility and to report on information that’s “most directly relevant to that work.”

“We do not report on the number of deaths because that is not the focus of the program,” she said.

To find that number, McClatchy counted all of the deceased workers in the government’s database who had qualified for federal compensation for illnesses linked to their work at 325 current and defunct nuclear sites.

And of the 33,480 deaths, the government has specifically acknowledged that exposure to radiation or other toxins on the job likely caused or contributed to the deaths of 15,809 workers. This tally certainly underestimates the total dead among the more than 600,000 who worked in the weapons program at its peak.

Bill Richardson, the former governor of New Mexico who served as energy secretary under President Bill Clinton, said the nation had an obligation to aid those who helped win the Cold War. He said the federal government had shown “a lack of conscience” in its decades-long refusal to provide compensation to injured workers who had legitimate claims against the government.

Congress passed the compensation program in 2000 after the Department of Energy (DOE) submitted studies that showed workers at 14 different sites had increased risks of dying from various cancers and nonmalignant diseases.

But Richardson said sloppy record-keeping at the nuclear sites made it difficult to predict the ultimate size of the program.

He said the program’s dramatic growth is a good sign, adding that no one’s getting rich, with individual payments capped at $400,000.

“I was unaware of these numbers. . . . Is it that big? Good,” said Richardson. “It’s helping people.”

The program’s size has triggered a hot debate, with critics saying the government has been far too generous in doling out benefits to employees whose cancer cannot be conclusively linked to their work.

“As a result, more than 12 billion dollars – that’s a B, billion dollars – has been distributed to people who now believe that they have been injured by the work that they did,” said Wanda Munn, a retired senior nuclear engineer who worked at Hanford in Washington state and who is a member of the federal Advisory Board on Radiation and Worker Health, a presidential panel that examines compensation claims.

Munn, a long-time board member, said the industry has a good safety record and there’s no proof of “excess cancer” among former workers.

Richardson said such talk is cruel to workers, many of whom have had to fight hard to win their compensation.

And Steve Wing, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health, said research has made the link between workers’ exposure to radiation and their cancers.

One study he led of workers employed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, for example, showed that there was a relationship between the radiation badge readings of the workers and their subsequent cancer death rates.

And even with the program’s rapid growth, more than half of the 107,394 workers who have sought help since 2001 – 51.1 percent – have been denied help, McClatchy’s investigation found.

On average, it takes 21.6 months for a claimant to get approved, while 20,496 workers spent five or more years navigating the bureaucracy.

The government’s data shows that one production worker at a defunct facility in Portsmouth, Ohio, had to wait 14 years for compensation.

Frustrated families say they believe the government has made the process more difficult for them in order to deter their claims and save money.

In an interview in August, George “Smitty” Anderson of Augusta, Ga., who developed multiple myeloma after working at the Savannah River plant for 17 years, said the entire claim process left him confused.

“I thought I was approved and shared it with my wife, and within no time at all it was disapproved,” said Anderson. He died on Nov. 5without ever getting compensated, despite years of trying.

Rachel Leiton, director of the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program, said the agency over the years has implemented shortcuts to ease access to the program for families.

“We try to the best we can to compensate them based on our statutory authority that we’re given. . . . It’s a non-adversarial system, the money is there to provide benefits to these employees,” she said.

Cost-cutting targets workers‘ health benefits

Today the federal government is embarking on a new round of investment in its nuclear arsenal, an ambitious effort estimated to cost upward of $1 trillion over the next three decades.

This year alone, the president budgeted $1.3 billion to upgrade aging nuclear weapons, a 21 percent increase over fiscal year 2015.

The plans include pricey upgrades, such as precision-guided tails for free-falling gravity bombs first built in the 1960s and nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missiles.

But even as the federal government ramps up spending on refurbished nukes, it has been looking for ways to cut costs. Much of the savings, it turns out, threatens to come at the expense of the health and retirement benefits for nuclear workers, as well as through voluntary job reductions.

At the Pantex Plant near Amarillo, Texas, where workers have the perilous task of assembling and disassembling nuclear warheads, a proposal to slash medical coverage, prescription plans, sick leave and defined benefit pensions prompted more than 1,100 unionized employees to walk off the job in August.

At issue was enforcement of an obscure Department of Energy regulation known as Order 350.1. The regulation mandates that DOE contractors periodically survey how much comparable businesses pay for their employees’ benefit packages and bring costs within 105 percent of the average.

The regulation also has led to benefit cuts at other nuclear facilities around the country, from Hanford Site in Washington state to the Y-12 National Security Complex in Tennessee.

At Pantex, strikers said they understood the need for the federal government to be frugal with taxpayer dollars. But they felt betrayed by the Department of Energy for enforcing Order 350.1 despite the history of occupational illnesses at Pantex and other nuclear sites.

The strike lasted for more than a month. When it was over, a DOE spokesman told McClatchy that Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz had appointed a task force to review Order 350.1.

The process, said the spokesman, Bartlett Jackson, “will refresh the policies DOE uses to stimulate our contractors to attract and retain the best and the brightest while delivering fair and reasonable costs to the taxpayers.”

Even with new safety standards, accidents persist

During the early days of the Manhattan Project and later during the frantic arms race of the Cold War, officials often chalked up injuries and contamination of nuclear workers as necessary sacrifices for national security.

Since then, safety standards have tightened dramatically. And yet accidents persist.

Federal investigators today often find that mistakes happened when contractors rushed work or cut corners – not to end a world war or outmaneuver the Russians, but to save money or earn bonuses.

The Department of Energy relies more heavily on contractors than any other civilian federal agency. Ninety percent of the DOE’s budget is spent on contracts and large capital asset projects, according to the Government Accountability Office. But the GAO has repeatedly criticized the DOE for inadequate management of its contracts.

Complacency also contributes to what the GAO has described as “lax attitudes toward safety procedures” by contractors.

Sixteen contractors have paid more than $96.7 million in fines for 33 safety violations related to radiation since 2001. Still contractors have pushed the DOE for more authority to police themselves – an approach that they refer to as “eyes on, hands off.”

The DOE says its safety record is very good, and that the average dose for workers with measurable levels of radiation is 10 times less than the average a member of the public receives every year from background radiation and diagnostic medical procedures.

But workers who are exposed today don’t always trust the government or its contractors to calculate their doses accurately.

A review of contractor misconduct files reveals that the falsification of radiation records does sometimes happen – most recently at the Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Ohio in April 2013.

Such incidents reinforce the fears of workers who’ve been injured or exposed to radiation in today’s ongoing nuclear research, weapons production and cleanup efforts across the country: that inadequate sampling and secrecy surrounding accidents could leave them without the proof they will need to qualify for compensation, should they fall ill one day.

“What happens in 15 years when I get bone cancer, or something else?” said Ralph Stanton, a nuclear facility operator who believes his dose from a 2011 accident at the Idaho National Laboratory was falsified. “I don’t get any help. I don’t get workman’s comp. I don’t get nothing.”

‘I know death is right around the corner‘

As the health inspector at the Savannah River plant, Vaigneur’s job was to protect others from radiation, but he couldn’t protect himself.

He was exposed when a production supervisor decided to bypass a high-level alarm system on a plutonium tank on the floor above his office. Even though there was little doubt that he had been exposed, he said it took him more than eight years to be awarded $350,000 for his breast cancer and chronic beryllium disease. He was denied three times.

After a doctor told him last year that he has less than a year to live, Vaigneur has already made plans to donate his body to Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Ga., hoping that researchers can learn something useful by studying how plutonium affected his body.

When the time comes, the federal government may not bother to count his death, but Vaigneur is a man at peace.

“I have a good outlook on life,” he said. “I know death is right around the corner. That’s part of living.”

Click here to read the full story and explore the data at McClatchy DC.

This story was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund of The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations. Other contributors: Yamil Berard, Fort Worth Star-Telegram; Mike Fitzgerald, Belleville News-Democrat; Rocky Barker, Idaho Statesman; Sammy Fretwell, The State of Columbia, S.C.; Scott Canon, Kansas City Star; and Annette Cary, Tri-City Herald.