The nine men were startled awake by pained groans coming from the bed where Nestor Garay slept in their small, shared cell. It was around 1:30 a.m. on June 26, 2014, at Big Spring Correctional Center in western Texas when several of them piled out of their bunks to check on Garay. He was unresponsive.

They called out to a corrections officer for help. Upon arrival at the prison clinic, according to medical notes, Garay remained unresponsive. His right hand was weak, and he’d urinated on himself.

When the morning nurse saw him at 6:15, Garay’s face was drooping and his right arm was contracted. It took more than an hour before he was delivered to the local emergency room, then flown to a larger hospital in Midland. There, John Foster, the neurologist who examined him, said that Garay had a stroke and that life-saving efforts after so many hours would be futile.

“Take him to the hospital; this man is dying,” one of the cellmates implored. Instead, Garay, 41, was prescribed an anti-seizure medication that he was unable to swallow and placed back in a cell.

Garay died, shackled to a hospital bed.

“The time to fix him may have been … when he fell out of bed,” Foster said.

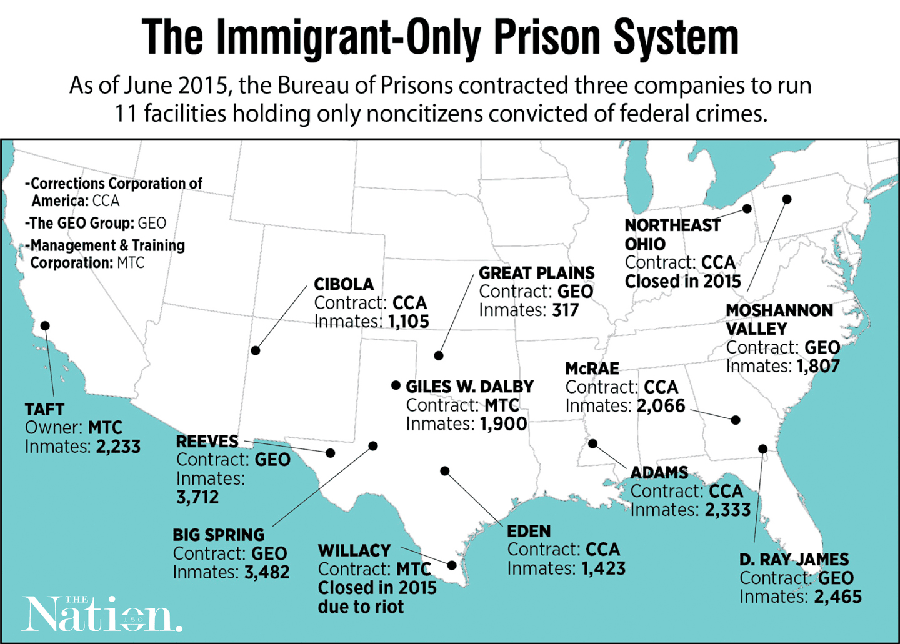

Big Spring is different from other federal prisons. It is one of 11 Bureau of Prisons facilities used exclusively for noncitizens. Some are held for crimes that anyone could commit: Garay was incarcerated for selling drugs. But of the nearly 23,000 inmates in this shadow prison system, 40 percent are serving time for immigration crimes, according to 2014 data – mostly “illegal re-entry,” or crossing back over the border after being deported.

And nearly unique within the federal prison system, private corporations operate all of these facilities. Five of them, including Big Spring, are run by The Geo Group Inc.; medical care in many of these facilities is provided by subcontractors.

Image: ANNIE ZHANG/THE NATION

The federal privatization experiment began in the late 1990s. President Bill Clinton had promised to rein in the size of the federal workforce, yet signed a crime bill bound to grow an already bloated federal prison system.

So, deep inside its 1996 congressional budget request, the White House tucked a plan to hire contractors to run four facilities. “The Federal Prison System,” it read, “will expand its capacity and cut costs through privatization.”

As of 2013, these prisons cost taxpayers $625 million a year. A Bureau of Prisons study found that the additional costs of monitoring the contracts may outstrip any cost savings they’ve produced.

Still, the facilities are now an integral part of the federal prison system. As recently as 2014, the Bureau of Prisons reiterated that noncitizens “were an appropriate group for housing in privately operated institutions where there are somewhat fewer programs offered to successfully reintegrate into U.S. communities.”

As I reported in The Nation, these private prisons were bound by a different, less stringent set of rules. Ever since they began operation in 1997, the facilities have been the target of complaints about shoddy medical care.

“These prisons operate without the same systems of accountability as regular Bureau of Prisons facilities,” said Carl Takei, an ACLU attorney who co-authored a report on the prisons.

At least five times since 2008, inmates at the facilities have rioted, largely over medical grievances. Yet the full scope of medical neglect has been opaque, until now.

In response to a public records request, the Bureau of Prisons recently released more than 9,000 pages of files. They contain the medical records turned over to the bureau of 103 men who died in these contract prisons from 1998 through 2014. They provide a penetrating look into medical care in this obscure subsystem – and contain indications of striking neglect.

The files tell the story of men sick with cancer, AIDS, liver and heart disease, forced to endure critical delays in care. They show medical departments repeatedly failing to diagnose patients despite obvious symptoms and the use of low-skilled medical workers pressed to operate on the margins of their legal scope of practice.

The case files and related evidence were reviewed by a panel of independent medical doctors. In 25 cases, reviewers found indications that inadequate medical care likely contributed to premature deaths.

Prison was not much of a risk when Eloy Flores first crossed the Rio Grande to Texas in 1990. Back then, the 19-year-old simply waded through the water and got a ride to Silver Spring, Maryland, where a friend said he could find work.

He started out as a day laborer there, then started running his own painting company. He married and, with his wife Miriam, had four children, all U.S. citizens. By the early 2000s, they had bought a house.

In 2008, the Floreses decided their American children should get to know Mexico and learn Spanish. They planned to relocate there for several years and return to the United States when their oldest son, Eduardo, was ready for college.

Their stay went as planned, until it was time to go back.

The border had transformed since Eloy Flores first arrived in the U.S. More than five times as many federal agents now roamed the desert, and border crossers had been forced into dangerous terrain.

In 2011, Eloy and Miriam Flores began their attempt to return. They would cross first, and then their kids would fly to Baltimore. Eloy Flores recalls being deported five times over three years.

On their most recent attempt, the couple was not immediately deported, but shuttled into a federal court in Del Rio, Texas, where they encountered a program called Operation Streamline. Launched in 2005 as a partnership between the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice, it was designed to expedite prosecutions for illegal entry.

The day the Floreses appeared in court, more than 80 men and women pleaded guilty to illegal entry in the space of two hours.

“You’re not being prosecuted for being a bad person or because you do not have good reasons,” Judge Victor Garcia told Eloy Flores, in an audiotape of the Nov. 18, 2013, hearing, before sentencing him to four months in prison. “I cannot stop you from coming back. But I can tell you what will happen if you do, and that’s you’re going to be in prison.”

That year, under President Barack Obama, prosecutions of illegal entry and re-entry reached a peak of 91,000. Flores and the rest had to be housed somewhere.

Indalecio Garay reads from a letter from son Nestor, who was incarcerated at a private prison in Big Spring, Texas. Nestor frequently sent his family letters enclosed in colorful, hand-drawn envelopes.Image: STAN ALCORN/REVEAL

After the sentencing, Eloy Flores was separated from his wife and put on a bus to Big Spring. While Miriam Flores only served 10 days, he was transferred to The Geo Group’s privately run prison in Big Spring. Even 18 months after his release, when I talked with him in the small Internet cafe he now runs in Atlacomulco, Mexico, he was rattled by his time there.

The cells were packed tight, as many as 10 men to a room, and he says the guards were aggressive: “You can’t even look at them.” Worse, he said, “I saw a lot of people there who were real sick.” And many of them, he said, “got no medicine.”

He felt like he’d dodged a bullet, arriving home safe and healthy, when, maybe six months later, he got a phone call that gave him chills. It was a former inmate from Big Spring, someone Flores had befriended there, an artist who often would sit in the prison’s bare common area to draw.

One of the artist’s regular sketching companions was a man named Nestor Garay, someone who was well liked there, known for sharing his snacks and stamps.

“He told me Nestor had died there,” Flores said. “That the prison didn’t care for him. … What I thought was, ‘That could be me.’ ”

Garay’s medical records describe a disaster, say the doctors who reviewed them. And many of the failings in the his case appear to be systemic, the result of a medical care system hobbled by cost cutting.

Bureau of Prisons-run facilities typically use registered nurses, physician assistants and nurse practitioners to perform routine medical care. But the contract prisons often employ less trained, less expensive licensed vocational nurses to do much of the same work.

“The fact (is) that the system, BOP and Geo, allows people to be short-staffed and in positions that they’re not properly trained for,” said Russell Amaru, a physician assistant at Big Spring.

During those critical early hours after Garay’s stroke, the only medical professional on duty was licensed as a vocational nurse, which requires one year of training. Amaru was the midlevel professional on call.

When he was woken up by a call from the nurse, Amaru said – and an internal prison review of the death confirms – the nurse did not properly communicate Garay’s symptoms. Nor was a vocational nurse qualified to perform a diagnosis of any kind.

Vocational nurses often appear in the 103 medical files reviewed for this investigation as the sole caregiver a sick prisoner sees for days or weeks. Medical reviewers said they also sometimes performed tasks beyond their capacities. In 19 of the case files we received, doctors flagged that as a sign of inadequate medical care.

The widespread use of lesser-trained staff does not appear to violate the Bureau of Prisons’ contracts with the private operators. To enable savings, the bureau allows these prisons to operate by less stringent rules.

“The more specificity you put in the contract, the more money the contractors are going to want for performing the service,” said Donna Mott, a recently retired Bureau of Prisons contract-monitoring official. “If you put in specificity exactly like (the) BOP … then it basically is going to cost them the same amount to operate their facility as it does a bureau facility.”

A former Big Spring clinical director, Dr. John Farquhar, complained openly in medical notes about the “shabby care” there and described directives to trim costs, including reducing emergency room transfers.

“The pressure of budget is always felt,” said Farquhar, who retired shortly before Garay’s death.

The Geo Group responded in a brief statement, writing that its prisons “adhere to strict contractual requirements set by the FBOP (Federal Bureau of Prisons) as well as all of the same policies and program statements enforced at FBOP-operated facilities.”

The private company’s medical subcontractor, Correct Care Solutions, said in a separate written statement that it provides a “comprehensive scope of healthcare services per our contractual obligations.”

Yet Mott said that because the contracts lack clear and specific requirements in many areas of operation, federal monitors “have no teeth to make the contractor do anything.”

The Bureau of Prisons’ contract with The Geo Group to run Big Spring is up for renewal this year.

This story was reported in partnership with Reveal and The Nation, with support from the Puffin Foundation.