Federal regulators earlier this month unveiled new rules aimed at reining in payday lenders and the exorbitant fees they charge. Now expect to hear a lot of what one payday lender named Phil Locke calls “the lies we would tell whenever we were under attack.”

The new rules announced by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are relatively straightforward, if not also a disappointment to some consumer advocates. A payday loan is typically a two-week advance against a borrower’s next paycheck (or monthly social security allotment, for that matter); lenders commonly charge $15 on every $100 borrowed, which works out to an annual interest rate of almost 400 percent. Under the CFPB’s proposal, lenders would have a choice. One option would require them to perform the underwriting necessary to ensure that a borrower, based on his or her income and expenses, can afford a loan. Another option requires them to limit the customer to no more than six of these loans per year (and no more than three in a row).

But floating new regulations is only one step in a drawn-out process. The CFPB’s announcement in Kansas City, Missouri, on June 2, at what it advertised as a “field hearing on small-dollar lending” (the agency also offered rules governing auto-title loans — loans using a car as collateral), begins a three-month comment period, which could lead to a congressional review phase challenging the rules. Payday and other small-dollar lenders spent more than $15 million on lobbyists and campaign contributions in 2013-14, according to a report by Americans for Financial Reform, “and I fully expect them to spend at least that much in the current election cycle,” said the group’s executive director, Lisa Donner. Already the House Appropriations Committee on June 9 approved an amendment that would delay implementation of any new rules that restrict payday loans. The coming months will offer lenders plenty of opportunity to try and derail the CFPB’s efforts.

Which is why the voice of Phil Locke is so critical at this moment, as policymakers debate the future of short-term lending in the U.S. Locke, who opened the first of his 40-plus payday stores in Michigan in 1999, figured he and his investors cleared $10 million in profits in his first 13 years as a payday lender. He built a $1.6 million home in a leafy suburb of Detroit and showered his wife with $250,000 worth of jewelry. For five years, he served as president of the Michigan Financial Service Centers Association, the statewide association formed to defend payday lending there. But by September 2012, he was calling himself “a Consumer and Anti-Predatory Lending Activist,” which is how he described himself in an email he sent to me that month. He had experienced a change of heart, he said, and had turned his back on the industry. He had sold everything to move into an RV with his wife and two young children, bouncing between mobile home parks in Florida. “I really feel my mission in life is to educate lawmakers on what predatory loans do to the working poor,” Locke told me at the time.

Locke’s speaking style is recursive — and he certainly harbors his share of grudges — but the details I was able to confirm almost always checked out. A stocky man with the lumpy face of an ex-boxer, Locke had tried out any number of businesses before turning to payday. He and a friend had opened a bar in Flint, where he grew up, but that only left him with a lot of credit card debt. He had tried — twice — to make it in what he demurely called the “adult entertainment industry.” He had then moved to Florida, where he tried getting into the reading-glasses business, but his first attempt, opening a mall kiosk, proved a failure. Somewhere along the way, he picked up a copy of Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal — the only book he had ever read as an adult, he told me — but didn’t have the patience to finish it. In 1999, he declared bankruptcy, which meant using a local check casher in Orlando as his bank. Someone behind the counter at a shop offered to sell him a payday loan — and he started noticing these storefronts everywhere he looked.

Neither Locke nor his wife, Stephanie, had any money. But the ubiquity of payday in the Sunshine State made him wonder why they weren’t yet everywhere in a Rust Belt state like Michigan. Locke was soon back in Flint, where he says he convinced his in-laws to borrow $150,000 against their home. That would be the grubstake that let him build his payday business.

Locke was in his mid-30s when he opened his first store, which he called Cash Now, in a small strip mall across the street from a massive Delphi plant in Flint. He wasn’t the first payday lender in town — a check casher was already selling the loans, and one of the big national chains had gotten there first — but he had little competition in the early days. His rates were high — $16.50 on every $100 a person borrowed, which works out to an APR of 429 percent. His advertising campaign was nothing more than the hundred “Need Cash Now” lawn signs that he and a friend put up around town the night before the store’s grand opening. He figured it would take months before he reached $10,000 per week in loans, but he reached that goal after three weeks. Within the year, he was lending out $100,000 on a good week and generating roughly $50,000 a month in fees. Occasionally a customer failed to pay back a loan, but most did and the profits more than covered the few who didn’t.

“Payday was like the perfect business,” Locke said.

In the spring of 2000, Locke flew to Washington, D.C., to join one hundred or so other payday lenders for the inaugural gathering of the Community Financial Services Association of America (CFSA, the Alexandria, Virginia-based trade group the payday lenders created to fight any reform efforts. “I was there when they were making policy,” Locke said. “I was there at the strategy meetings where we talked about fighting back against people who said payday loans were a bad thing.”

Locke learned how payday had come about at that first meeting of the CFSA. Allan Jones, one of the gathering’s chief organizers, took credit for inventing the modern payday lending industry. Another organizer, Billy Webster, who had worked in the Clinton White House, helped give the business legitimacy. Together, the stories of Jones and Webster explain the extraordinary rise of payday — an industry with virtually no stores at the start of the 1990s that reached a count of 24,000 by the mid-2000s.

Allan Jones opened his first payday store in 1993. Back then, Jones, who had bought a debt collection agency from his father, charged $20 for every $100 someone borrowed — an annualized rate exceeding 500 percent. After opening a second store, he consulted with a big law firm in Chattanooga, where a lawyer told him that he saw nothing in Tennessee law expressly forbidding Jones from making the loans. He opened seven more stores around the state in 1994. That year, his stores generated nearly $1 million in fees. “It was like we was filling this giant void,” Jones told me back in 2009. Over time, Jones grew Check Into Cash into a 1,300-store chain. (Jones was unhappy with my characterization of him in a book I wrote called Broke, USA and refused to participate in the writing of this article.)

Deregulation proved critical to the spread of payday lending around the country. Most states have in place a usury cap, a limit on the interest rate a lender can charge, typically under 20 percent. So Jones placed lobbyists on retainer, as did the competition that invariably followed him into the business. Their generous campaign contributions to the right politicians secured them sit-downs with governors and meetings with key legislators. These were once-in-a-blue-moon emergency loans, the lenders claimed, for those who can’t just borrow from their Uncle Joe or put a surprise charge on a credit card; certainly interest caps weren’t put in place to prevent a working stiff from borrowing a few hundred dollars until the next payday. Throughout the second half of the 1990s and into the early 2000s, state after state granted them their carve-outs, exempting payday loans from local usury laws. At its peak, the payday industry operated legally in 44 states plus the District of Columbia.

Billy Webster brought clout and connections to the industry. In 1997, Webster had teamed up with George Johnson, a former state legislator, to create Advance America. Where Allan Jones relied on subprime loans from an Ohio-based bank to grow his chain, Webster and Johnson used their connections to secure lines of credit at some of the country’s largest banks, including Wells Fargo and Wachovia. “We basically borrowed 40 or 50 million dollars before we made anything,” Webster told me in 2009. “We had an infrastructure for 500 stores before we had a dozen.” Advance America was operating around 2,000 stores around the country when, in 2004, the investment bank Morgan Stanley took the company public on the New York Stock Exchange. (Advance America was sold in 2012 for $780 million to Grupo Elektra, a Mexico-based conglomerate.)

It wasn’t too long after Locke opened that first store in Flint that he started eyeing locales for a second or third. The problem was that since his bankruptcy a couple of years earlier, “no bank would give me even a dollar to grow my chain,” he said. He was making good money, but he also figured he would need somewhere around $150,000 in cash per store just to keep up with demand. The answer, he decided, was to find investors.

“Cash Cow, Working Partners Needed”: That’s how Locke began the classified ad that he says he ran multiple times in the Detroit Free Pressstarting in mid-1999. The agreement he offered potential partners had them working together to find a suitable site for a new Cash Now store — no difficult task in the customer-rich southeastern corner of Michigan, a stand-in for the bleak state of the working class in post-industrial America. He would take on building out the store and the initial advertising, which he admitted meant basically buying a decent sign. The partner would be responsible for the cash a store would need to start making loans. Under the agreement, Locke said he collected 27 percent of a store’s revenues into perpetuity.

Locke spoke with dozens of would-be partners about the wonders of a business that let people earn more than 400 percent interest while their money was out on the street. He heard from any number of trust funders and also father-and-son teams, which basically meant a father setting up a ne’er-do-well son in business and not incidentally padding his own bottom line. Then there were the random people who had come into a large chunk of money, including a forklift driver and a former bartender. One older couple, a pair of empty nesters he met at a Starbucks just outside Flint, had qualms about the business. “They ask me, ‘How can you take advantage of people like that?'” Locke said. “I thought they were weird.”

Locke ended up going into business with around 30 partners. Together, they opened more than 40 stores, all of them in southeastern Michigan. Five were in Flint and five were in Detroit. Most of the rest were scattered around the Detroit suburbs. “That’s where we made most of our money,” Locke said.

By the mid-2000s, Locke claims he was clearing around $1 million a year in profits. He began collecting watches, including a Cartier, and also vintage motorcycles. His fleet of cars included a pair of Range Rovers, a Cadillac Escalade, a Lexus, a BMW, and a Mercedes. He and Stephanie bought land in Bloomfield Hills, one of Detroit’s tonier suburbs, and hired an architect to design a house for them. Locke initially figured they’d need no more than 4,500 square feet but approved plans for a house twice that size.

“I felt like a modern-day gangster,” Locke said.

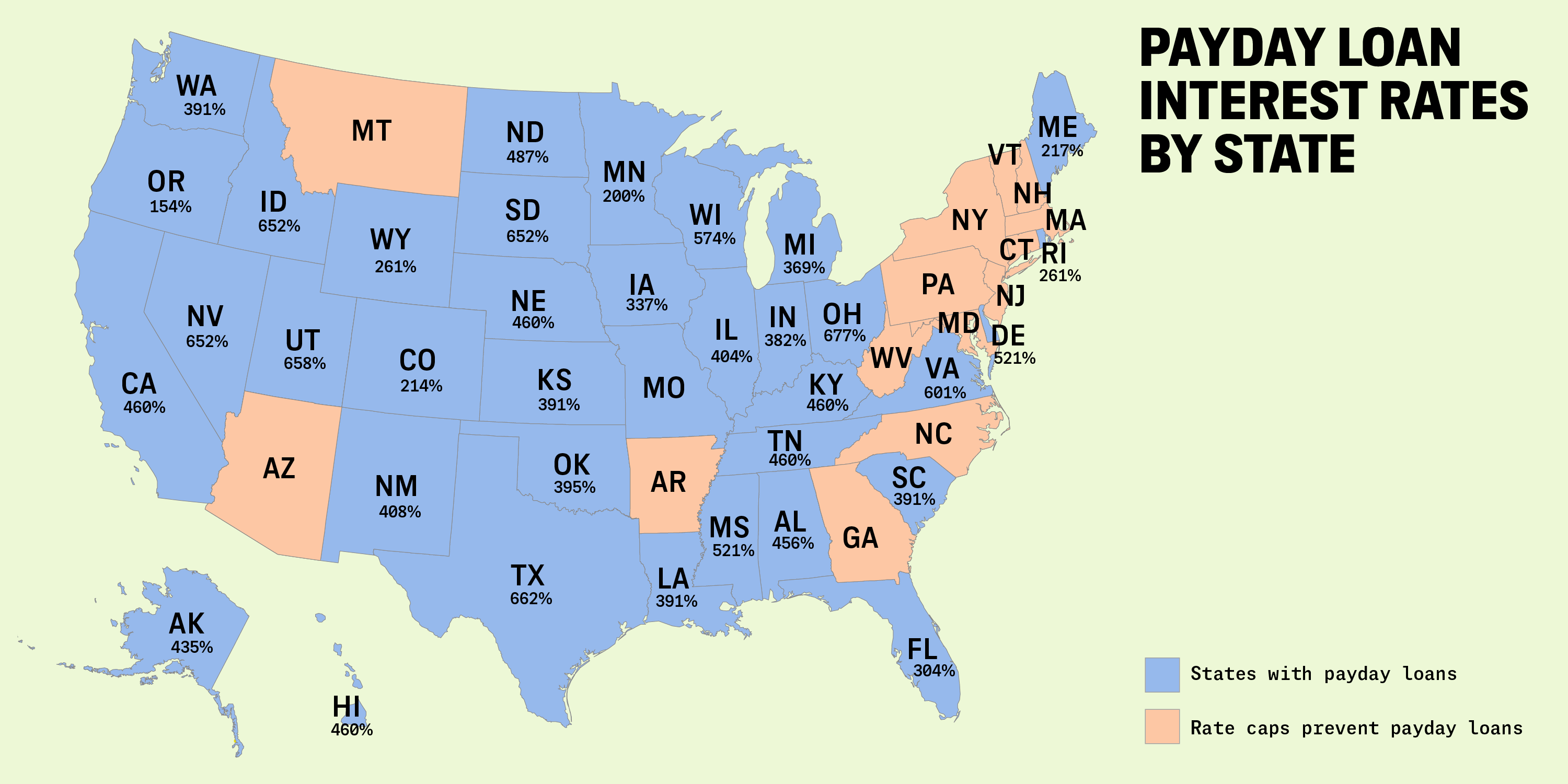

The state-by-state interest rates customers are charged on payday loans. The rates are calculated based on a typical $300, two-week loan.

But the researchers at Pew, who have been studying the payday industry since 2011 as part of the organization’s small-dollar loans project, believe the CFPB proposal doesn’t go far enough. “Proposed Payday Loan Rule Misses Historic Opportunity,” read the headline over a Pew press statement released on the morning of CFPB’s big announcement. Under the agency’s proposed underwriting provision, it would be hard to justify a $500 loan to someone taking home $1,200 a month if two weeks later the person would have to pay it back with a check for $575. Yet if the repayment terms required biweekly payments of $75 over 11 months, is that $500 loan really any more affordable?

“All these new rules are going to do is shift the market from 400 percent single-payment loans to 400 percent installment payday loans,” said Alex Horowitz, a senior officer at Pew. “We don’t see that as a consumer-friendly outcome.” According to Pew, an estimated 12 million Americans borrow money from a payday lender each year. In 2014, payday customers paid $8.7 billion in fees on $45 billion of loans.

Locke told me that a good store had between 400 and 500 customers at any given time — nearly all of them trapped in a loan they couldn’t repay. Eighty percent of his customers, he estimated, were in for a year or longer. “The cycle of debt is what makes these stores so profitable,” he said. There was Bobby, for instance, from a Detroit suburb. There was nothing special about Bobby; his file was in a batch Locke said he had grabbed randomly from a box of old records. (Locke let me browse through these records so long as I didn’t include anyone’s last name.) Bobby took out 113 loans between 2002 and 2004. A Detroit woman named Magdalene first showed up at one of Locke’s stores at the start of 2002. She paid $1,700 in fees over the next 12 months on the same $400 loan. Soon she was borrowing $500 every other week and eventually $800. In 2005 alone, she paid fees of more than $3,000 — and then several months later, she declared bankruptcy.

“I’ve had lots of customers go bankrupt,” Locke said —”hundreds” just at the two stores that he ran without a partner. These days, the dreams of millions hinge on a campaign to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. Based on a 40-hour week, that works out to about $30,000 a year — the annual earnings, Locke said, of his average customer.

“I ruined a lot of lives,” Locke said. “I know I made life harder for a lot of my customers.”

Even in his earliest days in the business, Locke recognized what he was doing was wrong. That was obvious when he told the story of a childhood friend who was a regular at his first store. The friend, who worked as a prison guard, was good for $500 every other week. He was a terrific customer, but Locke used to hide whenever he saw his friend coming in. “I’m embarrassed that I own this place,” Locke explained. “I’m embarrassed he’s paying me $82.50 every other week.” One day Locke confronted his old friend, telling him, “You can’t keep doing this. You’re a family man, you have kids.” Locke let him pay him back in small installments until he was all caught up.

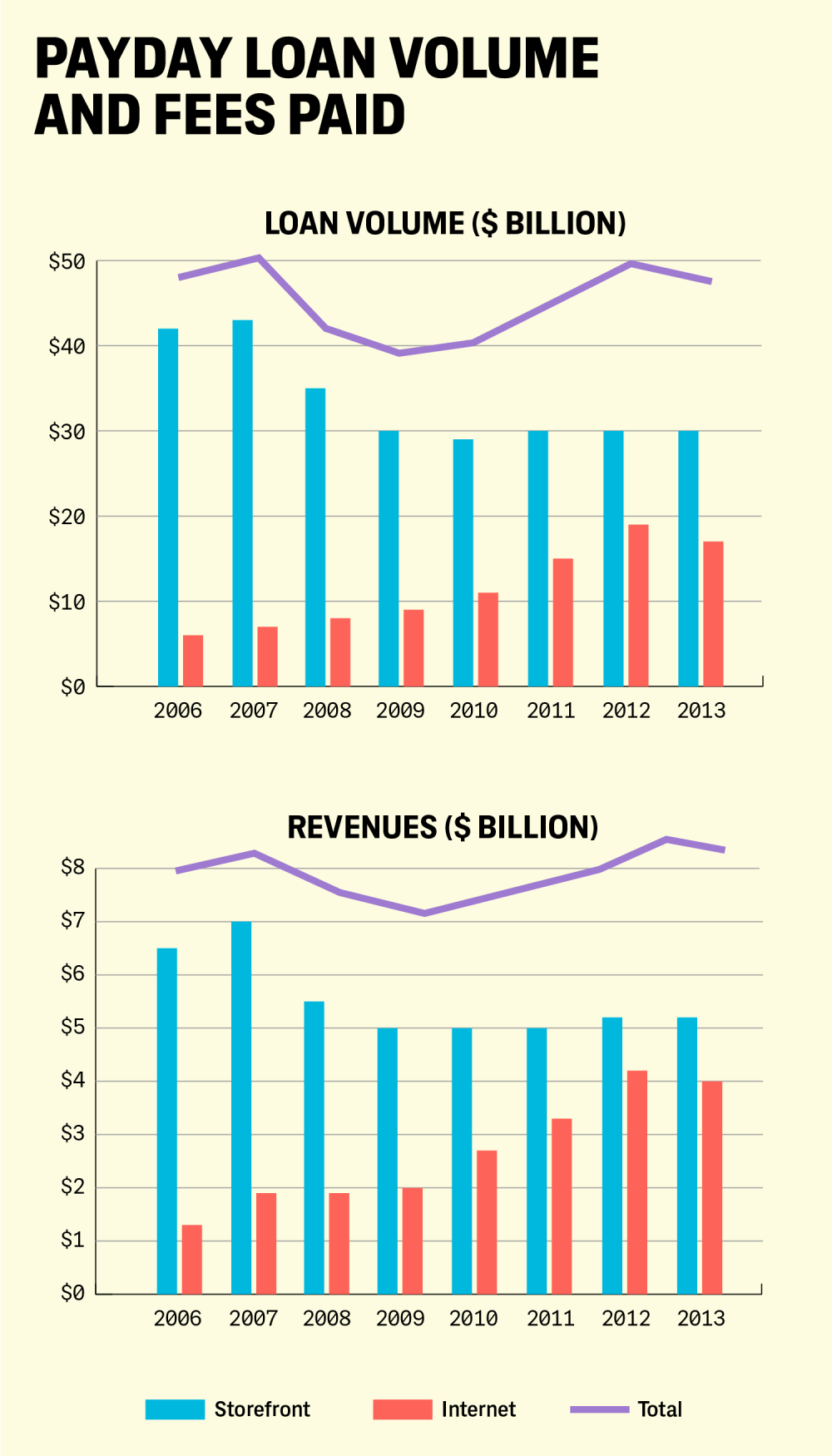

The volume of payday loans by year and the fees that customers pay, broken down by storefront and online loans.Image: STEPHENS, INC

Locke didn’t end up joining the CFSA, the payday trade group that Allan Jones and Billy Webster helped found. He was all in favor of its mission of fighting “any bills from Washington that put restrictions on what we could charge,” Locke said. But the dues were too steep in this organization dominated by the big chains. Like a lot of other smaller industry players, Locke joined the Check Cashers Association, which in 2000 renamed itself the Financial Service Centers of America, or FiSCA.

FiSCA encouraged its members to give $500 per store per year — for Locke, more than $20,000 a year. These contributions helped the group maintain a lobbying presence in Washington, among other activities. Locke was pleased when he was asked to join FiSCA’s board of directors but then realized the honor was an expensive one. “We’d get lists of PACs and individuals,” Locke said, and he was expected to write checks to all of them. They included the political action committees started by top names in Congress and also members of key legislative committees like House Financial Services. Locke told me he donated maybe $20,000 that first time, but he said he never gave anywhere near that amount again. (Records from the Center for Responsive Politics show he and his wife have given less than $10,000 total to members of Congress or FiSCA.) “I was much more focused on giving locally” to elected officials in Michigan, Locke said.

Locke took over as president of his state trade association in 2001, with his top priority to place payday on firmer legal footing. His five-year tenure was marked by a pair of bruising legislative battles in Lansing, the state capital. “I told a lot of lies in Lansing,” he said.

Michigan’s payday-loan trade existed then in a kind of netherworld. In other states, legislation had enabled payday lenders to operate legally within their borders, typically in exchange for a rate cap. In Michigan, though, Locke and every other payday lender operated via regulatory loopholes. State regulators looked the other way, and Michigan lenders were free to charge what they wanted. Locke’s rate was $16.50 per $100, but competitors were charging as much as $20 on every $100 loaned.

Locke and his allies hatched a plan in which they would trade enabling legislation for a rate cap of $15.27 per $100 (an APR of 397 percent) — or what he called the “27th strictest payday law in the country.” (Stated differently, by Locke’s calculation, 23 states allowed lenders to charge more than 400 percent.) They found a friendly legislator to introduce the bill in the state Senate in 2003.

Locke had always been a sweatshirt-and-jeans guy, even on the job. But he bought several suits in anticipation of the meetings he figured payday’s money would buy with members of the Michigan House and Senate. He told me he donated money to Jennifer Granholm, the state’s new Democratic governor, and also to Michigan’s new attorney general. (The Michigan secretary of state appears to have no record of these contributions.) Locke also encouraged his members to donate to key legislators. Both the House and Senate approved the bill, but Granholm, who had only recently taken office, vetoed it.

They tried again in 2005. In May of that year, Locke and others held a strategy session with several legislators, including a committee chair Locke described as a “friend.” “The thing we asked is, ‘What can we tweak to make sure she signs it this time?'” Locke said. They kept the same rate but made small changes in the bill’s language. Locke claimed his group also raised an extra $300,000 to help ensure passage. They already had a lobbyist on retainer, but the extra money allowed them to add five more, including the firms of former Attorney General Frank J. Kelley and an ex-speaker of the House, and hire a PR firm to help them hone their message.

Locke’s nemesis that legislative session proved to be not a consumer advocate or an ambitious liberal but Billy Webster, the Advance America co-founder. Several years earlier, Webster had helped champion a bill in Florida that capped payday lenders’ rates at $10 per $100 — and for his troubles, he had been slammed by his fellow payday moguls. But Webster didn’t care. Lenders could still make money in Florida on loans earning more than 250 percent interest — and maybe even quell a growing backlash among consumer groups. “The industry’s worst instinct is to confuse reform with prohibition,” Webster told me. “We should reform the industry where it’s necessary.” On behalf of the CFSA, he negotiated a slightly more consumer-friendly deal in Michigan than the one Locke was proposing.

The bill Webster backed allowed stores to charge customers $15 on the first $100 borrowed but $14 on the second $100, $13 on the third, down to $11 for every $100 above $500. That would mean Locke’s Cash Now, which once could charge $82.50 on a two-week $500 loan, now would earn only $65, which works out to an APR of about 340 percent. For Webster, a 20 percent drop in revenue would be the cost of doing business in Michigan. The smaller local players, however, felt betrayed, none seemingly more than Locke. “The CFSA came in and tried to force this law down my throat,” he said. The lower rate would translate into lost jobs, Locke complained in sit-downs with legislators. It would mean more boarded-up storefronts around a state that already had too many of them. “‘We need higher rates’ — that’s what we were all brainwashed to say,” he told me.

The ensuing battle, which took place in the second half of 2005, was like Godzilla versus King Kong. Like Locke’s organization, the CFSA had a battalion of lobbyists in its employ, as did several of the big out-of-state chains. “It was a nasty, nasty, ugly battle of politics and our state association didn’t have the deep pockets to keep donating money,” Locke said. Night after night, Locke claims he watched as the CFSA picked up the tab at yet another fancy restaurant in Lansing for any legislator wanting to eat and drink. A couple of legislators he says he knew well told him about the private jet the CFSA had sent to ferry them and their wives to Palm Springs for a CFSA conference.

Locke tried to fight back. He told me one of his lobbyists set up a dinner with an influential legislator from Detroit. The legislator chose five appetizers and then, for his main course, ordered the “most expensive fucking thing on the menu.” The legislator also chose a $300 bottle of wine that he barely touched and then, because he said he had to run, asked for a pair of crème brulées to go. During the meal, it became obvious that his guest had already sided with the CFSA. “The guy burned me for an $800 dinner when he knew there was nothing he was willing to do to help us,” Locke said.

Predictably, the legislature backed the slightly more consumer friendly CFSA bill, which Granholm signed into law at the end of 2005. Soon thereafter, Locke stepped down as head of his statewide association.

Despite his dire warnings, Locke and his partners continued to thrive in Michigan. But partners who were once clearing $100,000 or $120,000 per store were now worried about making even $75,000 a year, and they came to resent sharing their profits with the man who was seemingly in a position to protect them but didn’t. A group sued Locke, alleging “unfair and oppressive” conduct. The case eventually settled, but other suits followed.

“I took a forklift driver making $16 an hour to $300,000 a year,” Locke said, but the man sued him. The childhood friend he brought into the business didn’t take him to court, but the two no longer speak. Through it all, Locke blamed his woes on Granholm, who had refused to sign the 2003 bill he had worked so hard to pass. “I was lying in bed till 3 p.m. every day,” Locke said, “dreaming of killing Jennifer Granholm.” Eventually, he went to a psychologist. Mainly that meant talking, he said, about “my hatred for Jennifer Granholm.”

BY THE SPRING of 2012, Locke was fighting with his business partners, more than one of whom he suspected of stealing from him, and feeling more than fed up with an industry populated, he said, by the “greediest bunch of bastards I’ve ever seen.” He spoke, too, of the role religion played in his decision, in 2012, to turn on his old colleagues. He decided to become a whistleblower — a former insider who goes rogue to let the world know that rather than helping people, he was peddling a toxic product that left most of them decidedly worse off.

Locke not only abandoned the business, but he also sold most of his possessions, including his house and most of the jewelry. “We sold our grand piano,” he said. “We sold a lot of our artwork.” He even got rid of the suits he had bought to lobby in Lansing. “I said, ‘We’re freaking selling it all,'” Locke said. “I just wanted to rid myself of it.”

Locke wrote to Oprah Winfrey. He reached out to Howard Stern, Ellen DeGeneres, Nightline, and 60 Minutes. He contacted the Today Show and stressed his Flint roots when trying to contact fellow native Michael Moore. He flew to Hollywood in the hopes that someone would want to turn his life story into a movie or television show. But rather than fame and attention, he got a taste of life as a public-interest advocate. “Nobody cares about the poor,” he concluded. Locke wrote a short book he called Greed: The Dark Side of Predatory Lending that no one read. He claims he spent around $25,000 producing a hip-hop-style documentary few people watched. “It really was a waste of time. And money,” Locke said. “This whole effort has been … It’s got me back in depression.”

By the time Locke and I got together for a couple of days in early 2013, around a year after he had launched what he sometimes called his “crusade,” he was already feeling discouraged. He had imagined regular trips to Washington, D.C., where he would serve as a witness whenever his expertise was needed by members of Congress and others pursuing reform. His first trip to the nation’s capital, however, had proven a bust. He had contacted more than two dozen members of Congress, but only one agreed to meet with him: a Detroit-area Democrat who would serve a single term before being voted out of office. Locke spent $3,000 on a full-page ad in Politico. The idea was to draw the attention of legislative staffers, advocacy groups, journalists, and maybe even the White House with a promise to tell “the truth” about predatory lending. But the ad, Locke said, failed to elicit a single phone call or email message. He spent several thousand dollars attending the 2012 Democratic convention in Charlotte, North Carolina, only to be ignored.

Spending time with Locke in Michigan often meant listening to long rants about the lack of gratitude among the partners he had brought into the payday business, despite all the money he had made them. “Friends screwing me over,” Locke said. “Business partners screwing me over. People who begged me to get them into the business — screwing me over.” He’s kind of a human Eeyore who wears his disappointment as an outer garment. Of his customers, Locke said, “I feel bad for these people.” But he seemed to feel sorry mainly for himself.

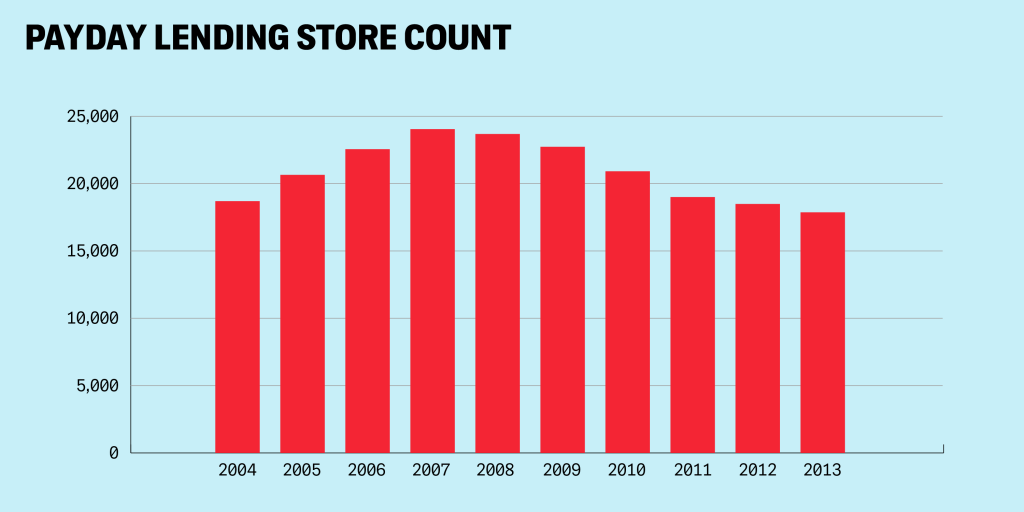

Rise and fall in the estimated number of payday stores across the United States as select states have fought back against these higher-priced loans.Image: STEPHENS, INC

From the start, the payday industry recognized that a new financial protection agency posed an existential threat. Locke spoke of the “constant” warnings FiSCA and the CFSA sent out while Congress was debating Dodd-Frank, the financial reform package that created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The CFSA’s annual lobbying bills underscore those fears. The CFSA spent $2.6 million on lobbyists in 2009 and another $2.4 million in 2010. It spent another $2.3 million on lobbyists in 2011, when the CFPB was still taking shape, and $2.6 million in 2012. Even so, in 2012 the CFPB announced its intention to investigate the payday lending industry. The bureau didn’t have the authority to set a nationwide rate cap, which would require congressional action, but under Dodd-Frank, it has broad powers to stop practices it deems “unfair, deceptive, or abusive.”

The payday lenders have turned to Congress for relief, as have the banks, subprime auto lenders, and other financial players now in the sights of the CFPB. Every year, more bills are introduced in Congress that either would weaken the bureau or thwart one of its rulings. For a while, Americans for Financial Reform kept a running tally of the industry-friendly bills, “but we stopped counting at 160,” said the group’s Lisa Donner.

The focus now, however, is on the proposed CFPB rules and the comment period. Between now and then, both the payday lenders and their opponents will share their disappointment. “Everyone wants the CFPB to be the savior,” said Nick Bourke, who directs Pew’s small-dollar loans project. “But while they’re improving the situation in some ways, without changes there will still be a lot of bad things happening in this market to the tune of billions of dollars of costs to consumers.”

That’s good news for Phil Locke. At the end of 2013, more than a year after dramatically switching sides in the fight over payday, Locke got back into the business. His wife missed the trappings of their old life. So did he. He was a working-class kid from Flint who had dropped out after a semester or two of college. He had only so much money in the bank and two young children. What else was someone like him supposed to do? And — despite his harsh words about the industry — it turned out he had been hedging his bets all along: He hadn’t actually sold or walked away from his stake in Cash Now but only had transferred ownership to his mother.

“I gave it a shot just to see what I could do,” Locke told me. “It didn’t work out. I had to return home.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations.