June 25, 2012, was a terrible day for Jermaine Robinson. Overall, life was good—the 21-year-old Washington Park resident had been studying music management at Columbia College and was a few weeks into a job working as a janitor at a nearby Boys & Girls Club. But his 13-year-old neighbor had been killed by random gunfire the previous day, and Robinson spent the evening at an emotional memorial service.

After the service ended around midnight, Robinson repaired to his girlfriend’s house on Rhodes Avenue to hang out with friends and to see his one-year-old daughter, he says. But just after midnight, he says, several Chicago police officers rammed down the side door of the house and burst into the living room.

Police would later say that they had spotted Robinson dashing from the front porch into the house holding a revolver. According to police reports, the officers found a handgun in the house, which they claimed belonged to Robinson. They arrested him and two other young men. At the precinct, in a cinderblock interrogation room, Robinson says he told police he was only visiting the home and knew nothing about the gun.

But by the time of his arrest, Robinson was well acquainted with Cook County’s criminal justice system. He had grown up poor in the Ida B. Wells Homes in Bronzeville, where his great-grandmother, a retired CTA bus driver, struggled to raise him, his mother, and a dozen other grandchildren. “It was sometimes seven of us in one bed,” Robinson recalls. At times he’d skip school because he feared that his student uniforms were so smelly and unclean they’d draw derision from his classmates.

By his mid-teens, he’d started dealing cocaine and heroin, and at 17, he was arrested on drug and weapons charges. Although still a minor, he was charged with a felony and booked into Cook County Jail. After entering a guilty plea, he says, he spent the rest of his teens downstate in the Vienna Correctional Center. In 2011, Robinson says, he spent another several months in prison after being caught with a small amount of marijuana.

But upon his release later that year, Robinson says he was striving toward a different path. He’d taken two courses in music management at Columbia that spring, and he hoped to return. His dream, he said, was to cultivate the talent of musicians he knew across the south side. His girlfriend was seven months pregnant with a second child, and the future seemed to hold promise.

The arrest at the house in Washington Park marked a sudden end to Robinson’s hopes. He feared his past convictions would cast him in a suspicious light in front of a judge and jury.

“My case was basically my word against the police’s word,” he says. “So by my being a convicted felon, my credibility was already shot.”

In the early hours of the morning, Robinson recalls, he was transferred from the police precinct to Cook County Jail, a 96-acre complex of bleak concrete cell blocks stretching along California Avenue on the southwest side.

Although no court documents indicate that the state had any physical evidence linking Robinson to the gun, a judge denied his request for electronic monitoring and set his bond at $7,500—the amount he’d have to pay in order to be released from jail and resume work and school as he awaited trial. It was a sum neither Robinson nor his family had at their disposal. Robinson’s family set out on the first of numerous failed attempts to raise the money while Robinson stayed in jail waiting for his case to be resolved.

As Robinson reacclimated to life behind bars, he noticed something that dismayed him: a few of the inmates he’d met during his first spate in jail as a teenager were still there now, awaiting trial.

“There were guys there still fighting their cases from when I first came to the county in 2007,” Robinson said. “These guys were in there for six, seven years.”

He didn’t yet know it, but Robinson was about to join their ranks. Although formally innocent in the eyes of the law, he would spend 1,507 days in jail—more than four years—awaiting trial for the weapon-possession charges.

The Sixth Amendment of the Constitution grants anyone accused of a crime the right to a speedy trial. But a 2014 New Yorker profile of Kalief Browder, who was incarcerated as a teenager in New York’s Rikers Island jail and held for three years awaiting trial, catapulted the issue of pretrial detention into the national spotlight and demonstrated that this constitutional mandate isn’t always enough. In June 2015, two years after his release, Browder committed suicide at age 22. In April of that year, the New York Times reported that Browder’s case wasn’t an isolated occurrence. Of the approximately 10,000 inmates at Rikers at that time, more than 400 people had been awaiting trial for at least two years.

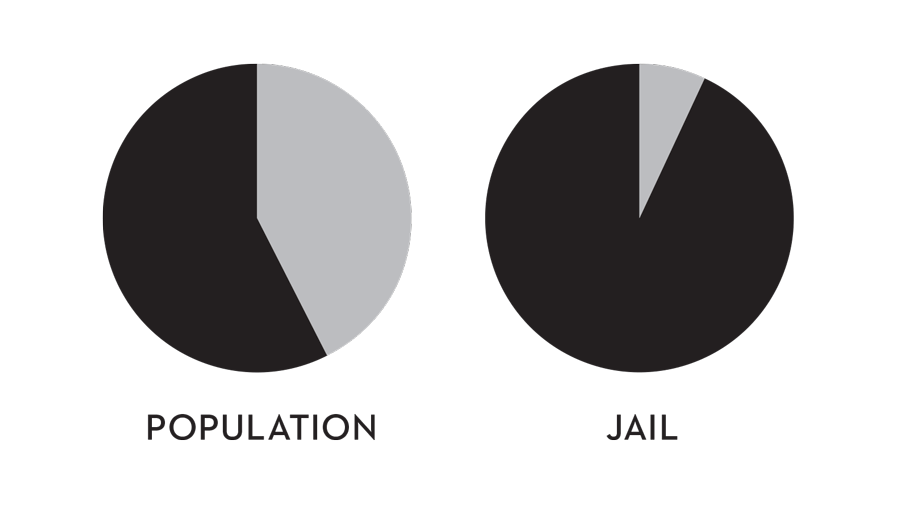

Now, a joint investigation by the Reader and the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute has found that although Cook County Jail has fewer inmates than Rikers did then—roughly 8,000—it holds more than double the number of inmates awaiting trial for multiple years. More than 1,000 Cook County inmates have been awaiting trial for more than two years, according to the Cook County sheriff’s department. In some extreme cases, some have been held without trial for more than eight years. Minorities account for 93 percent of these long-waiting inmates, an even higher percentage than the jail’s overall population. Only 11.5 percent of Cook County inmates are white, as are a mere 7 percent of its long-term pretrial detainees. (The racial breakdown of the jail’s population is already strikingly disproportionate to the county’s population as a whole, which is 42.6 percent white.)

Most inmates awaiting trial for multiple years in Cook County face charges for violent crimes such as murder, rape, or assault. But, according to the sheriff’s department, nearly half of them have been held not because they’ve been deemed too dangerous for release, but simply because they couldn’t post bond. (The problem of pretrial inmates being held because they can’t afford even small bond amounts is so widespread that on Monday Cook County sheriff Tom Dart proposed abolishing the state’s cash bond system altogether.) According to a recent report from the Chicago-based journalism nonprofit Injustice Watch, less than 3 percent of the jail’s population are serving a post-conviction sentence; the rest are still awaiting trial or sentencing.

But poverty isn’t the only cause of prolonged pretrial detention, our investigation finds. Dozens of attorneys, court administrators, and inmates interviewed for this story—plus a highly critical report from the Department of Justice—paint a picture of a court system plagued by unnecessary delays. Court systems around the country are crippled by overwhelmed public defenders and overscheduled courtrooms, but Cook County defendants also face judges and police commanders who fail to ensure that officers appear in court when needed and a state crime lab so overburdened it can take up to a year to turn around basic DNA samples.

Perhaps most troubling, some defense attorneys who choose to invoke Illinois’s speedy trial law—which requires the state to seat a jury within 120 days for defendants in custody—claim to have faced prosecutorial or judicial retaliation.

The Cook County state’s attorney’s office, which oversees more than 1,500 prosecutors and administrative employees, declined to be interviewed for this story and didn’t respond to a list of questions. In a statement, the office of Cook County circuit court chief judge Timothy Evans said that a complicated host of factors contributes to trial delays and that the office had launched a series of initiatives to study the problem and implement best practices.

Attorneys agree that complex criminal cases may legitimately take a lot of time—sometimes years—to adjudicate.

Nevertheless, the consequences for defendants of such lengthy trial delays are severe, and raise troubling questions about the unequal application of justice in Cook County. Extended trial delays deprive defendants of their liberty for months or years as they await trial, causing them to lose jobs, incur debt, fall behind on schooling, and endure separation from loved ones.

Perhaps more disturbingly, numerous studies have shown that lengthy trial delays mean defendants are more likely to plead guilty and less likely to be acquitted at trial as compared with those able to bond out of jail. More than one former Cook County inmate said that after being held under pretrial detention for years, they’d concluded that their only way out of jail was to plead guilty for crimes they maintain they didn’t commit.

“Defendants are much more likely to take pleas just because they want to get out of jail,” says Max Suchan, a private defense attorney and a founder of the Chicago Community Bond Fund.

“That,” he says, “happens in Cook County every day.”

Although formally innocent in the eyes of the law, Jermaine Robinson spent more than four years awaiting trial on weapon-possession charges.Image: DANIELLE A. SCRUGGS/CHICAGO READER

Believing the state had no substantial evidence against him, Robinson hoped that his case would be tossed out quickly—perhaps in time for him to return to his studies at Columbia that fall. But as registration came and went, Robinson remained in jail, struggling to get his defense off the ground. His family hired a private attorney, then began falling behind on payments; this set off several months of uncertainty about who exactly would represent him, according to the Cook County public defender’s office, which took up Robinson’s case in early 2013.

Roughly once every month or two, guards would wake Robinson up at 4:30 AM, put him in shackles, and lead him onto a bus whose windows were mostly covered by steel plates. As the sun began to rise, he would arrive at the courthouse in west-suburban Bridgeview, where he says he would wait with dozens of other inmates in a cramped basement holding area. As noon approached, Robinson would be called to appear before a judge. Each time, the hearing would last for only a minute or two, Robinson recalls, before the judge would decide, for an array of reasons, that his case wasn’t ready to move forward.

“Then it would be another continuance,” Robinson says—and another month or two in jail.

As he faced continuance after continuance, Robinson tried to readjust to life inside the jail. His cell was infested with spiders and cockroaches, he says, that crawled on him at night and made it difficult for him to sleep. Yet jail’s greatest indignities, Robinson says, came from people. To Robinson, the jail felt like a concentrated version of the rivalries and violence of Chicago’s streets.

“They take those old-fashioned shampoo spray bottles and make a concoction with their feces, urine, and all kinds of other stuff, and spray it on people or throw it on people,” he says of his fellow inmates. “I guess it’s the next best weapon to a gun in Cook County Jail. They do it to disrespect people; it makes you feel real low.”

When he was drawn into tussles, guards would send him into “the hole”—solitary confinement—for weeks at a time, Robinson recalls. There, he was alone, with nothing to distract him from the incessant screams and moans of inmates in neighboring isolation cells. (According to the Cook County sheriff’s office, typically 25 to 30 percent of Cook County Jail inmates suffer from mental illness.) Periodically, his neighboring inmates would cover their cells with their own feces, filling the block with a smell so intense that it would make the guards vomit. Once, Robinson says, he saw a shackled inmate attempt suicide by throwing himself over a stairwell banister.

As Robinson’s case meandered through the court system, weeks turned into months, and then a whole year passed, yet he wasn’t any closer to trial.

When I reached out to Robinson’s family in January, he had been awaiting trial for nearly four years. His great-grandmother had passed away in 2008, leaving his mother, Lasheena Weekly, to battle her son’s prolonged trial delays. Robinson had spent four months in jail as his public defender fought to obtain personnel records on his arresting officer, Anthony Bruno, records that his judge then took months to review. Before that, Robinson had waited five months just for the court to hear, and reject, a motion to reduce his bond.

Although she believed that the facts of the case were going Robinson’s way, Weekly faced a problem that has particularly vexed many Cook County defendants: although under subpoena to testify at a hearing on a pretrial motion to quash the arrest, Bruno had repeatedly missed court dates, causing months more delays.

In December 2015, Robinson’s public defender, Rosemary Costin, issued a subpoena warning Bruno that his failure to appear at the next hearing, scheduled two months from then, would result in him being held in contempt of court. Still, when that court date arrived, Bruno was nowhere to be seen.

Robinson’s judge, Thomas Davy, set a new court date six weeks later, to try again. Costin issued another subpoena for Bruno to appear. When that date in late March arrived, Bruno was in court, according to records—but in a different courtroom, apparently on a different case. This time, one of Robinson’s witnesses also failed to appear; she had forgotten the court date altogether. Costin issued another subpoena for Bruno to appear. At the following hearing almost two months later, Bruno was again absent. Costin issued yet another subpoena. Five weeks later, Bruno again failed to appear.

“It’s been prolonging and prolonging and prolonging,” Weekly said. “They want to get [Robinson] tired of being in that awful place and get him to admit to something that he did not do.”

Robinson marveled at how the state handled Bruno’s absences.

“Had it been the other way around, and I’d been subpoenaed to court and didn’t show up,” Robinson told me, “there would be a warrant out for my arrest.”

In 2005, the U.S. Department of Justice, with American University, released a study into how the Cook County Criminal Court manages felony cases. Primarily seeking to understand the relationship between lapses in courtroom efficiency and overcrowding in the jail, the report found that the court system suffered from “a ‘legal culture’ that facilitates unnecessary delay in case processing.” A major driver of this, according to the study, was startlingly simple: as in Robinson’s case, police officers were continually failing to show up for court hearings that hinged on their presence as witnesses.

Police absenteeism not only runs afoul of state laws meant to ensure that witnesses appear in court; it also violates the Chicago Police Department’s own rules of conduct, which specifically prohibits officers from failing to report promptly when called to court. Yet the study noted that police absenteeism “does not appear to generate any sanctioning” of the officers themselves. Daniel Coyne, a defense attorney and clinical law professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law at the Illinois Institute of Technology, confirmed the DOJ findings on no-show officers in a 2007 paper.

More than a decade after the DOJ study was published, little appears to have improved in Cook County when it comes to reliably getting officers to show up to testify. Officers failing to appear in court continues to be a stubborn contributor to pretrial delay.

“I haven’t seen any change in this problem,” says Coyne, who mainly represents defendants facing serious felony charges. “It really hasn’t been getting much better.”

Defense attorneys and court administrators echoed Coyne’s concern over police witnesses failing to appear.

“Lately, it’s worse than it’s ever been,” adds Bill Murphy, a private defense attorney who’s been practicing in Chicago for nearly 50 years.

In fact, the backlogged dockets of Cook County’s overburdened courtrooms mean that, when an officer fails to appear at a hearing, it can take months to try again.

“It’s rarely like, ‘OK, let’s meet next week,’ ” says Michael Bianucci, a private defense attorney who has worked in Cook County’s criminal courts for 26 years. “No, you’re often talking three months later. If that happens a couple of times, nine months is gone. It’s unbelievable.”

“These are not witnesses like other witnesses,” says Keith Ahmad, a top supervisor in the Cook County public defender’s office. The court is “very reluctant” to issue warrants for police witnesses who repeatedly fail to come to court, Ahmad says—warrants that would often be standard issue for other witnesses who fail to appear. “I’ve never seen a warrant issued for a police officer.”

In interviews, several other long-serving pretrial inmates and their families cited police truancy as a factor in prolonged jail stays. Some also said it had contributed to a feeling of pressure to give up on getting their day in court and simply enter a guilty plea in order to return home from jail.

Falandis Brown, a former security guard, spent 16 months in Cook County jail awaiting trial on a burglary charge, accused of taking a GPS device from a Ford Explorer parked along the Midway Plaisance near the University of Chicago campus. Brown says that the failure of a police officer to appear at his trial was part of why he pleaded guilty this past January, despite privately maintaining his innocence, in order to free himself from jail. In exchange for his plea, prosecutors allowed Brown’s 488 days of pretrial detention to count toward his sentence, which would also include several weeks in state prison. (The CPD declined to comment on Brown’s case, and a spokesperson for the University of Chicago Police Department, which assisted Brown’s arresting officers, said that its officers appeared at all of Brown’s court dates.)

“They told me the police weren’t there, and they weren’t ready for trial, and I was looking at, I think, a 94-day continuance,” Brown says. “I couldn’t sit any longer, man. I just took the plea.”

Twenty-nine-year-old Chante Johnson has been awaiting trial for more than five years—2,040 days as of press time—facing charges in connection with the armed robbery of a liquor store in the suburb of Blue Island. His family cites no-show police as one of many factors delaying his trial; court records document multiple notations of “witness ordered to appear,” though they don’t specify which witness.

“What about Chante’s right to a speedy trial, what about the prosecutor proving and presenting a case without all these holes in it?” his grandmother, Gloria Johnson, asked in a 2015 letter to chief judge Timothy Evans. “They have taken four and a half years of his life away, and it’s like nothing to them.”

Johnson is scheduled to appear in court again Thursday.

Meanwhile, late last July, Bruno finally appeared in court in Robinson’s case.

Robinson says that, under questioning from lawyers, Bruno provided answers regarding Robinson’s arrest that left Judge Davy visibly unsatisfied. After Bruno’s testimony, Davy granted Robinson’s motion to quash arrest, meaning the police had no grounds to take him into custody in the first place. Two weeks later, the state dropped all charges against Robinson. After being held in jail for more than 1,500 days, Robinson was free to leave.

The Reader attempted to contact Bruno for comment, both directly and through the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 7, the police union. Bruno didn’t respond, and the FOP said it was unable to reach him.

CPD also declined to make Bruno available, but provided a statement to the Reader about the larger issue of police absenteeism. Between January 2010 and August 23 of this year, CPD recorded 11,698 instances of officers failing to appear in court, according to department spokesman Sergeant Michael J. Malinowski, although the department doesn’t distinguish in its record-keeping between instances when the officer has permission to be absent and instances where he or she does not.

“Whether it be an excused absence, their presence was required in another courtroom at that time, maybe the officer wasn’t notified etc. There are a number of reasons” why an officer might legitimately miss a court date, Malinowski said in a statement.

Still, Malinowski says, the department “takes court absentees very seriously,” and investigates each instance.

But when asked what portion of these absences had been investigated and found to be impermissible, and what the consequences were for officers found in violation of the department’s court policy, Malinowski declined to comment.

Minorities make up 57.4% of Cook County's population but account for 93% of inmates waiting more than two years in Cook County Jail.

In extreme cases, defendants have spent years in pretrial detention waiting for their arresting officer to appear in court. This was the case for 56-year-old Kermit Leaks, who on April 20, 2012, was arrested in North Lawndale for having allegedly stolen two semiautomatic rifles the previous day. The rifles and other gear, it turned out, had belonged to then-CPD SWAT team member Johnny Quinones, who says he’d left them in the car. In Leaks’s arrest report, police allege that they found Leaks and his codefendant, Michael Calvin, in possession of the stolen guns.

By the time Leaks had spent six months in jail, he was already fed up and filed a complaint with the state. In the letter, Leaks argued that his prolonged pretrial detention appeared to be a tactic on the part of the prosecution that his public defender was doing little to oppose.

“It’s only [an] effort to drag their case out in hopes of getting a plea,” Leaks wrote. “My due process is being violated.”

But for Leaks, who was never able to afford his $30,000 bond, this was only the beginning.

After more than three and a half years awaiting trial, Leaks sent me a letter. Over the past two years, one obstacle had prevented him from getting his case to trial, he says: Leaks’s arresting officers repeatedly failed to appear at more than a dozen of his pretrial hearings, setting off a seemingly endless cycle of continuances. Court records document 15 continuances after unnamed witnesses failed to appear. (More than a dozen officers are listed on Leaks’s arrest report, but because there are no subpoenas in Leaks’s available court records and the Cook County state’s attorney’s office declined to comment, the Reader was unable to determine which officer or officers had failed to appear in court.)

This past November, in a letter to the public defender’s office, Leaks again pleaded for help. His court-appointed attorney seemed unable to get his case moving, he said.

“Could you please! have a talk with my public defender about assigning her some help?” Leaks implored the state.

Over the span of his lengthy pretrial incarceration, Leaks’s life had changed significantly. He had been beaten by jail guards and forced to sleep on a filth-covered cell floor for weeks at a time, he alleged in a federal complaint. And he had been diagnosed with leukemia.

He was on the brink, he wrote me, of admitting guilt to a crime he still insists he didn’t commit—known among inmates as “copping out”—in order to free himself from jail.

“I wake up every day wanting to [plea],” Leaks wrote, “but my first mind tells me don’t cop out for something you know you didn’t do.”

An attorney in the Cook County public defender’s office, who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity because he feared that speaking on the record could cause judges to disfavor his cases, said that Leaks’s “storied past”—a criminal record that included convictions for drug charges and manslaughter—would pose a tough hurdle at trial for a defendant many jurors would assume was guilty. The attorney confirmed that there had been an unusually long wait for Leaks’s police officer to appear in court.

“We’re trying to get him in,” the attorney said. “He isn’t coming to court, and that delays the case, but it’s not sufficient to dismiss the case.”

“When you can’t get an officer to come to court, you have to keep trying,” he added. “Nobody is issuing bench warrants for cops who don’t show up.”

Starting on February 11, 2014, Leaks’s case entered a spiral of repetition. That date marked the beginning of hearing after hearing recorded in Cook County courtroom logs with the bare notation: “Witnesses ordered to appear,” indicating that a hearing has been postponed while a no-show witness is subpoenaed.

On January 26, 2016, after two years of these circular court appearances, I sat in Judge Kevin Sheehan’s courtroom to watch one of Leaks’s hearings. It turned out to be typical. Leaks entered in shackles, and less than a minute later—after an inaudible exchange took place between Sheehan, Leaks’s defense attorney, and the prosecutor—Leaks was led back to jail without having said a word. In courtroom logs, the hearing is recorded as yet another “witnesses ordered to appear.” Sheehan set Leaks’s next court date for eight weeks hence, in the spring.

That June, after Leaks’s arresting officers finally came to court, the state offered Leaks a deal: If he would plead guilty to the state’s charges, the years he’d served in jail would account for his entire sentence, and he could walk free. So, on June 23, after more than four years of resisting, Leaks entered a guilty plea. (His codefendant, Michael Calvin, with whom Leaks was arrested in 2012, is still incarcerated in Cook County Jail awaiting trial.)

The Reader attempted to contact all of Leaks’s arresting officers for comment, both directly and through the FOP. They didn’t respond to our requests.

Upon his release in late June, Leaks moved in with a lifelong friend, Ray Yarbrough, who says he attended dozens of Leaks’s hearings. They had another friend who owned a trucking company across town, and Yarbrough and Leaks talked about going to school together to get truck-driving certification to take advantage of the company’s available jobs.

But life on the outside proved difficult for Leaks. The jail had sent him home with only a week’s worth of medicine for his leukemia, Yarbrough recalls, and, after this ran out, Leaks struggled to obtain refills on his own. As his days without medication ticked by, Leaks began complaining of pain throughout his body.

Just over a week after Leaks was released, he was found dead at a friend’s house in North Lawndale. According to county records, Leaks had overdosed on a mixture of heroin, cocaine, and fentanyl.

“He was in a tremendous amount of pain,” Yarbrough said. “I think that led him to go get the drugs.”

Although the failure of police to appear in court was central to Leaks’s frustrations, for many defendants, it’s just one of an array of factors that drag their cases on for years.

Several attorneys cited the Illinois State Police’s overburdened crime lab as another routine contributor to unnecessary delays. The problem is so bad that a March 2016 investigation by the Chicago Sun-Times revealed a backlog of nearly 3,100 cases with biological evidence—such as hair, blood, or semen—that were either untested or in the process of being tested more than 30 days after they had been submitted to the lab, up from just 130 in 2009.

The state often takes months to turn around DNA evidence for serious cases involving murder and rape, says Eric Bell, a criminal defense attorney who has practiced in Cook County for nearly 20 years. “It can take more than a year.”

In an e-mail to the Reader, the Illinois State Police defended its handling of the backlog, asserting that a state law passed in 2010 mandating the testing of rape kits from old investigations had contributed to significant delays. As those kits have been cleared, the ISP is working, according to agency spokesperson Sergeant Matt Boerwinkle, to reduce its current backlog.

“The total ISP Lab backlog statistics have decreased each year for the last five years,” Boerwinkle said, citing a drop from more than 17,000 total backlogged cases pending in 2012—including not only biological evidence, but evidence related to drugs, guns, prints, tracks, and other matters—to 12,568 at the end of last year. (The Sun-Times found that the subset of cases with biological evidence waiting more than 30 days had actually risen by 19 percent from 2015 to 2016.)

Still, state crime lab backlogs have remained severe enough that some Illinois cities have recently delegated funding to outsource their evidencetesting to private firms rather than wait hundreds of days for results from the state.

Daniel Coyne, the clinical professor and defense attorney, says he recently represented a man who had been held for five and a half years awaiting trial for murder. (Through Coyne, the client declined to comment, and Coyne declined to share his client’s name or records, saying he wanted to protect him from reputational harm.) Coyne says in that case, it took the state lab more than 11 months to conduct DNA tests and produce reports.

At trial in December 2015, Coyne’s client was finally acquitted, he says. However, “he lost five and a half years of his life waiting to go to trial.”

Several defense attorneys also argue that the state drags its heels during the discovery process, during which time the defense’s hands are tied. Going to trial without the ability to review the state’s full set of evidence would imperil any defendant. Sometimes prosecutors take more than a year to complete discovery, even for defendants awaiting trial in jail, according to several attorneys.

“After a number of years of practicing in Chicago, I thought that was the norm,” says defense attorney Rodney Carr, “until I started going to seminars in California or other jurisdictions and hearing how quickly things are wrapped up, go to trial and discovery is tendered.”

In October 2013, Timothy Hooper, now 64, was arrested in his car and charged with more than 100 counts of identity theft: police alleged that he’d been making fake IDs. Hooper claimed that he was innocent of all charges but, unable to afford his $50,000 bond (later reduced to $25,000), he was booked into Cook County Jail.

Hooper has an extensive criminal record dating back to the early 70s, including, most recently, a 2010 fraud case in Michigan. He’s also an army veteran who suffers from degenerative arthritis, and his arrest came after his wife, Darryl, had undergone a double mastectomy for breast cancer—a time when Hooper said they had come to rely heavily on each other. At first, Hooper says, he believed there had been some mistake, and hoped to be out of jail within days. But weeks turned into months as Hooper waited for the state to turn over any evidence against him to his public defender.

Every so often, Hooper and his lawyer would meet, but instead of discussing his defense, Hooper claims she would encourage him to accept the prosecution’s offer and plead guilty to all 105 felony charges in exchange for a reduced sentence, which he recalls was more than ten years. Insisting on his innocence, Hooper refused.

“I’m 64 years old,” he said. “That’s like a bullet in the head.”

A year passed as Hooper waited in jail. Hearing after hearing ended in continuances as the prosecutor repeated that the state needed more time to gather and process evidence, Hooper says. Court records show that Hooper made two motions for discovery.

“The judge told me to not fight the case without having all of my discovery,” Hooper recalls. “So I said, ‘Your honor, it’s been two years—I’m ready for trial, but the state keeps saying they’re still getting stuff together. Don’t they have a time period they have to meet? Or can they just go on?’ It didn’t make sense to me. I was saying, ‘I only have so much time, why don’t they only have so much time?’ ”

The chief judge’s office declined to make the judge in Hooper’s case available for comment.

Court records show that, in December 2013, Hooper fired his public defender and began representing himself. (In a statement, the Cook County public defender’s office said it was unlikely that Hooper’s attorney would’ve encouraged him to plead to all 105 charges.)

Then, in May 2015, after Hooper had spent 18 months in jail, the state’s case began to falter. Hooper still doesn’t know what exactly changed, but suddenly, in the middle of that month, prosecutors dropped 104 of the 105 charges against him, according to court records. With his wife struggling at home, Hooper says he felt he had no choice but to plead guilty to his final charge—an admission he claims was false—in order to return home to help her. Last December, after serving seven months in the Centralia Correctional Center, he arrived home.

Such delays are not always the fault of the state, some attorneys argue. As cases stretch on, defendants sometimes run out of money to pay a private attorney, necessitating a potentially time-consuming switch to a court-appointed attorney, as happened with Robinson. Although there has been little documentation of this in Cook County, intentional delays by defense attorneys have been detailed on the part of certain defense attorneys in Bronx criminal courts. In fact, defense attorneys may benefit from delays, since “state witnesses can disappear, die, or their memories can fade,” says Darren O’Brien, a former prosecutor who spent 30 years in the Cook County state’s attorney’s office.

But O’Brien, now a private defense attorney, insists that defendants frustrated by long waits in jail can request a trial using the state’s speedy trial law.

“The fact is that the defendant holds the key to how long he stays locked up,” he says. “Because if he says those words, then 100 percent of the time the case will go to trial or be dismissed.”

Numerous other defense attorneys interviewed for this story, however, say that it’s almost impossible for the defense to demand trial without jeopardizing a client’s interests. Once the defense has demanded trial, judges may not allow defense attorneys to pursue the pretrial motions that are often essential to get a defendant’s case dismissed, to get the charges reduced, or to properly prepare for trial.

And even if defendants do get to a point where they are ready to demand a speedy trial, they can potentially expect blowback from the prosecution or judges, according to several defense attorneys who practice in Cook County.

“Demanding trial is like calling the state’s attorney’s mother a bad name,” says the public defender who requested anonymity. “Prosecutors take it very personally when you demand trial.” A trial demand means that an already busy prosecutor must put everything else aside and focus on preparing for trial, he explained, or else face potentially serious repercussions for exceeding the term.

“It’s considered the nuclear option,” Coyne says. “In my 32 years of practice, I can count on two hands the number of times I’ve demanded.”

One of the stipulations in Illinois’s speedy trial law is that, once a defendant begins the 120-day clock on a trial demand, the defendant and his or her attorney must appear in court for all scheduled appearances; if a defense attorney misses a single court date, the speedy trial clock can stop. To prevent these constitutional demands from advancing, several public defenders and private defense attorneys allege, some prosecutors will purposely schedule a trial on a date when they happen to know that the defense team has an irreconcilable conflict.

Even a former prosecutor acknowledges that this happens. “I have heard of that and I always thought that was a rotten thing to do,” O’Brien says. “I’ve heard guys saying they’ve done it or are going to do it. I’ve never seen it done, and I’ve never done it.”

In rarer instances, some Cook County judges have reacted to defendants’ use of the speedy trial law with hostility, according to several public defenders. They say that these judges have sometimes required an inmate who makes such a demand to return to court with his or her attorney every single day, first thing in the morning, for the entire 120-day duration of the demand. This forces an inmate to be dragged out of bed at 4:30 AM daily to go wait in the courthouse’s underground holding pen for hours to appear at one useless hearing after another. For public defenders, with their packed schedules, such a time commitment is simply untenable.

It’s meant to “punish the inmate in order to dissuade them from demanding or to make them back off the demand,” according to Carr, the Cook County public defender. “I have seen that happen.”

“The speedy trial is more of a fiction than anything,” said Murphy, the private defense attorney, who says prosecutors’ moves to thwart a trial demand are inevitable. “It just can’t be done.”

The number of times CPD officers failed to appear in court—with or without permission—between January 2010 and August 23, 2016.

Leaning into a small conference table in his fifth floor corner office—with its floor-to-ceiling tinted windows overlooking a lunar expanse of cell blocks—Peter Coolsen, the administrator of the criminal division of Cook County’s court system, cautioned against oversimplifying the issue of trial delay.

“It’s not any one thing,” Coolsen said of the problem’s causes. “It’s the whole combination of factors working together.”

Coolsen’s job is to help the division’s presiding judge, LeRoy Martin, come up with ways to efficiently move thousands of cases through the court system each year. Coolsen says the issues that lead to trial delays—including the changing of defense attorneys and prosecutors on a case, the backlogged state crime lab, and no-show police officers—have been the subject of much discussion within the court system. (The chief judge’s office didn’t respond to a request for an interview with Martin.)

“I’ve been absolutely preoccupied with this for the past few years,” Coolsen says.

“The culture of the judiciary is really important,” he adds. “Everyone has to feel a sense of urgency.”

The Chicago Community Bond Fund’s Suchan, who’s studied the court system extensively, agrees with Coolsen but singles out judges as the players with the most power to effect the necessary reforms.

“The chief judge and the presiding judge of the criminal division—both of those judges have the ability to push back on this culture of disregarding the urgency of how long cases take,” Suchan says.

He also emphasizes that judges have a disproportionate influence over the pace at which a case moves through the system. “The judges set the schedules for the courtroom,” he says. “They can say: this is when something must happen.”

In charge of a judicial bench that oversees more than a million pending criminal and civil cases on any given day, the job of Cook County’s chief judge, Timothy Evans, certainly has its challenges, and Evans’s tenure has not been an easy one. In September, after a judicial misconduct scandaland a critical assessment from the state supreme court on the county’s criminal case management, Evans narrowly prevailed in a judicial election that the Chicago Tribune characterized as unusually acrimonious, fueled by widespread discontent with Evans’s leadership.

A 2013 study on pretrial delay in Cook County published by the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice, a court-reform advocacy organization, found that “no internal policy enforces the use of” informal standards created by the chief judge’s office on how quickly various types of cases should be resolved. In its recommendations, the report focused on the role of judges. In particular, the study suggested that judges receive mandatory training and mentorship to become better at moving cases with appropriate speed.

In a statement to the Reader, Evans’s office emphasized the shared responsibility between all parts of the court.

“In order for case delays to be reduced in this complex, interdisciplinary criminal justice system, it would take more than the judges of the Circuit Court of Cook County to effect significant changes,” said spokesman Pat Milhizer. “All stakeholders in the system would need to examine their internal processes as they relate to case-flow management.”

Milhizer also touted several initiatives intended to speed up cases, including efforts to reduce time from arrest to arraignment and the streamlining of aspects of bond court, as well as recent grants the court has received to study and improve its case management.

Citing the results of a 2013 review initiated by the chief judge, Milhizer indicated that CPD has itself acknowledged, and is taking steps to solve, its contribution to case delays.

“The Chicago Police Department is addressing issues that can cause delays,” Milhizer said, “such as the time needed for producing 911 tapes and video, prompt notice to the court by officers who are witnesses of schedule conflicts with dates for testimony, assuring officers bring required evidence to court, and the time needed to produce final police reports.”

Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve, an assistant criminal justice professor at Temple University who has extensively studied the Cook County Court system, believes that the police department could do a better job enforcing its rules of conduct when it comes to court absences, a problem which she says prosecutors can find themselves helpless to address.

“This really impacts people’s lives and liberty and one would think that such power would be concentrated in the hands of prosecutors,” she said, “but what we see is that police officers wield a lot of power, and there’s certainly not enough consequences coming from the police department itself when these types of violations occur.”

Coolsen stopped short of criticizing the police department, but suggested that a more robust system of communication between prosecutors and police precincts about court dates could be a starting point in addressing police absenteeism.

Yet even if this solved the problem of police absences, it would constitute only a sliver of the reforms necessary to tackle pretrial delay in Cook County. Coolsen says the sprawling court system will need to adopt new, lasting attitudes and practices guided by the need to fulfill the constitutional imperative of a speedy trial. He also claims the court is already taking steps to tackle the problem.

Last July the court received federal funding for a wide-ranging study of case-flow management in its criminal division. Part of this will include testing the efficacy of a judge giving an order at the outset of some cases, laying out how much time it should take to be resolved based on how complex a given case is, according to Coolsen.

“[T]he main emphasis is on the court building an expectation among the various players that cases will take as much time as they need for a fair and just resolution of a case, but not more,” Coolsen said in an e-mail. “It is that ‘culture of expectation’ that we are trying to build in the Criminal Courthouse.”

“We can certainly do better,” Coolsen added. “But it’s only going to happen if we get a regular, sustainable, and systemic approach where we’re all sharing the same vision.”

But while potential fixes to Cook County’s court system crawl forward, they may not be fast enough for the hundreds of inmates stuck in jail for years awaiting trial. In 2013 Robinson’s younger sister died in a house fire. His inability to mourn with his family remains one of the worst traumas he says he suffered during his grim years awaiting trial.

After his release in August, Robinson moved in with his girlfriend on a quiet block in South Chicago, just across the street from the grassy, overgrown expanse of the old U.S. Steel South Works plant. When I met Robinson at their home in September, he mentioned that one of the only places he’d ever been outside of Chicago was the downstate penitentiary where he spent the last two years of his teens. Now that he’s free again, he hopes to eventually travel the country, perhaps to visit New York City and get his first glimpse of the Atlantic Ocean.

For now, however, Robinson’s focus is getting back on his feet in Chicago. He says he plans to reenroll in college—at Columbia, he hopes. But his most immediate priority is earning a living: in recent weeks, Robinson has applied for a cashier job at a nearby Dunkin’ Donuts and for several temporary positions at janitorial agencies. He’s also been attempting to make up for lost time with his children, now four and five years old.

“I’ve been through a lot,” Robinson says. “I’m just happy to be back here.”

Marc Daalder, Maya Dukmasova, Jack Ladd, Jaime Longoria, and Sharon Riley contributed reporting to this story.

This article contains a correction. A 2013 study by the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice was incorrectly referred to as a 2010 study by the Chicago Appleseed Foundation.

This story was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations.