On the morning of Oct. 13, Taslima Aktar arrived at the gates of a Bangladeshi factory called Windy Apparels, in the industrial suburb of Ashulia, where she had been employed as a sewing operator for a year. For two weeks, the 23-year-old had complained of a fever and a hacking cough; her supervisor had refused her repeated requests for time off. Ten years in the garment industry had taught Taslima the costs of missing a day’s work without permission — especially before a big order had to be shipped out. As a young woman from the countryside, this job, at a large garment factory, was her only ticket out of rural poverty. Getting fired was simply not an option.

When she walked onto the factory floor that day, she already felt faint, but when she approached her line manager about going home early, he refused her again. Shortly afterward, she passed out and was rushed to the factory clinic, only to be sent back to her sewing

Later that evening, her co-workers found her body stowed near the factory gates. They were told management was waiting for her husband to finish work at a nearby factory and pick up her corpse, one explained to me. “This is how little they value our lives,” said a colleague, who, along with a local labor advocate, Taslima’s mother, and other co-workers, reconstructed the events of the day. “We know the same thing can happen any day, to any of us.”

I visited Ashulia, just outside Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, in October — three and a half years after the deadliest industrial accident in the history of the global garment industry. The Rana Plaza collapse fatally buried more than 1,100 workers beneath piles of rubble, and I wanted to learn whether Bangladesh’s garment factories had become any safer in the years since. Ashulia is at the beating heart of the country’s garment industry and lies not far from where Rana Plaza once stood. I spoke to Taslima’s colleagues and acquaintances, as well as others who had not known her, on a Friday, workers’ weekly day off here, and the dirt roads running along the traffic-choked highway to Dhaka were buzzing with activity. That day, I met with more than a dozen workers from a few large factories. To a person, they all spoke about what had just happened to Taslima.

They were angry about the circumstances of her death. Many said supervisors had routinely denied requests for sick leave for anyone who wasn’t violently ill. One described a co-worker being warned she would be fired if she didn’t return from sick leave after a single day. None of them wanted me to use their names; they were all scared of losing their jobs. When I asked about the new safety regimes implemented after the Rana Plaza collapse, they didn’t want to talk about the structural improvements or the new fire safety measures. Taslima’s death had shattered their illusions of safety.

“The building is safer, but as workers in the factory we still don’t have any security in our lives,” one woman who worked at a factory called Ayesha Clothing Co. Ltd. told me. “Even if I am on my death bed, they will ask me to finish making two more pieces before I die,” she added. “We are nothing but machines to them.”

Bangladesh is one of the cheapest places in the world to make clothes, and its plentiful supply of inexpensive labor has made it second only to China in global apparel exports. The garment industry employs nearly 5 million people. Since rural migrants began pouring into the city in the early 1990s seeking work in the burgeoning industry, the population of Dhaka and the industrial zones that encircle it has grown threefold. With nearly a third of the country’s population living below the national poverty line, the $23 billion ready-made garments sector (which accounts for more 80 percent of the country’s exports and roughly 15 percent of the GDP) is widely seen as an economic lifeline for the nation.

On April 24, 2013, the dreams of a sweatshop-led path out of poverty got a rude jolt. That morning, an eight-story building housing five garment factories collapsed, killing 1,134 men and women, most of whom were crushed to death under concrete and iron as they were making clothes for dozens of international brands. Reporters and labor activists sifting through the debris found links to Benetton, JCPenney, Joe Fresh, and The Children’s Place, among others; records later connected other major brands to the plant, including Walmart. The carnage at Rana Plaza made headlines around the world and finally forced the estimated $3 trillion global apparel industry to contend with the deadly costs of cheap fashion.

The disaster inspired what hundreds of factory fire deaths since the 1990s had not: the adoption in 2013 by more than 70 signatories — mainly European retailers and apparel brands, led by Swedish giant H&M — of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a compact developed by international and Bangladeshi labor unions. Signatories — now more than 200 — are bound to a five-year agreement that requires factories producing clothing for them to undergo independent safety inspections and make upgrades to adhere to uniform standards. Reluctant to sign on over concerns about legal liability, North American retailers including Walmart, Target, Macy’s, Nordstrom, and Gap Inc. (which includes Old Navy and Banana Republic) signed onto a separate, industry-influenced safety plan called the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which now includes 29 U.S. and Canadian companies.

Today the Accord and the Alliance say that together they have inspected roughly 2,000 factories in Bangladesh for structural, electrical, and fire safety, most of which have at least begun a process of remediation. Buyers that are part of the agreements are expected to stop sourcing from factories that fail to make the required improvements. Another approximately 1,500 factories make clothes for buyers that are part of neither compact and fall under a separate regime of government-led safety inspections known as the National Tripartite Action Plan.

“In terms of fire and building safety, I can honestly say I feel a little more comfortable now,” labor activist Kalpona Akter told me in her bustling office at the Bangladesh Centre for Worker Solidarity in Dhaka. “It could be a lot faster, the brands should be helping more, and I still don’t fully trust the government inspections, but there’s definitely been an improvement. At least now everyone is talking about safety.” She draws a sharp distinction between the Accord and the Alliance, charging that the latter is not transparent and less serious about safety.

- “They are asking for gold” for repairs, “but only paying silver” for the garments themselves.

Factory owners say the two agreements have something in common: an unfunded mandate when it comes to paying for safety upgrades. Syed Qamrul Huda, chairman of the Arunima Group, showed me around one of his Ashulia factories — Arunima Sports Wear — which supplies clothing to Gap, Target, Walmart, and Wrangler and is thus covered by the Alliance. An entire wing of the nine-story building, including elevators and the main stairway, was under repair. “It’s all part of what we have to do to make our factory compliant with the kind of safety the brands want,” he explained, pointing out shiny new fire doors, fire extinguishers, fire alarms, and prominent signs on every floor, announcing “Safety First.” Making these improvements has cost the company nearly $1.5 million, Huda told me. He said the cost would have pushed him into bankruptcy if the company wasn’t large and well-respected enough to secure a nearly $1 million loan from the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank. For smaller factories that lack access to large lines of credit, he said, remediation remains prohibitively expensive.

While both accords require participating brands to pay for inspections, neither requires companies to pay for the safety improvements themselves — which, according to the International Labor Organization, could total nearly a billion dollars nationwide. Under the Accord, brands and retailers are supposed to negotiate with suppliers to make it “financially feasible” for factories to upgrade. Rob Wayss, executive director of the Accord, told me brands typically commit to maintaining their orders if factories upgrade, and might even pay for some orders in advance, but acknowledged that the “overwhelming majority” of the factories pay for their own remediation. Alliance country director and former U.S. Ambassador to Bangladesh James F. Moriarty said by email that Alliance brands have helped negotiate $100 million in low-cost loans to upgrade supplier factories. He said the Alliance takes workers’ rights “very seriously” and runs safety trainings, reaching 55 plants so far, as well as a confidential worker help line, which captures issues of concern that are raised with factory managers or buyers. But a compliance manager at a large factory covered by both the Alliance and the Accord, who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity, said the brands effectively hold factories hostage: “They are asking for gold” for repairs, “but only paying silver” for the garments themselves.

The attention to building and fire safety might indeed prevent yet another fatal factory fire or collapse, but little in the new agreements addresses the unfair labor practices that are endemic to the industry and endanger the safety of workers like Taslima Aktar. Windy Apparels, where she worked, did not respond to queries. But the plant is on the list of Accord suppliers, so I asked Wayss what protections the agreement offered workers like Taslima. He said denial of sick leave could be considered a health and safety violation: “If it were brought to our attention we would investigate it and at the very least we would forward it to all the parties, so the brands and the unions would be aware of it.” But he said no one filed a complaint about the prolonged denial of sick leave to Taslima. Possibly because there was nothing unusual about it.

Under Bangladeshi labor law, workers are entitled to 14 days of paid sick leave each year. That protection was codified in October 2006, after a wave of worker protests and wildcat strikes that summer brought garment production to a standstill. Bangladesh’s labor law was amended again in 2013, in the aftermath of Rana Plaza, to ease organizing and expand health and safety protections. As labor unions have noted, the amended law still has holes, especially when it comes to protecting workers’ freedom of association, and even the legal protections that do exist often go unenforced by the Ministry of Labor’s Department of Inspection. On the factory floor, the law is simply no match for the demands of the market — and the outsized power of the garment owners.

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, or BGMEA, is one of the most powerful trade bodies in the country. According to Transparency International, 10 percent of lawmakers are themselves directly involved in the garment industry, and some of them serve on government committees on labor and commerce. Labor activists in Bangladesh point out that an even greater number of lawmakers have indirect financial ties to the garment industry, through close relatives. The political clout garment factory owners wield, they argue, remains the main obstacle to enforcing labor rights.

One of the largest garment conglomerates in Bangladesh is the Palmal Group, which owns 19 factories and employs more than 25,000 workers. The founder, Nurul Haque Sikder, was a pioneer in the industry and served as vice president of the BGMEA in the 1990s. Earlier this year, Gap released a list of its suppliers around the world, including 52 in Bangladesh. At least five factories on the list are owned by the Palmal Group, including Ayesha Clothing in Ashulia.

- “We didn't even have time to use the restroom because we had to meet our quota.”

“Taslima Aktar’s death,” a sewing operator at Ayesha Clothing told me, “is the logical outcome” of the way employees there are made to work. In October, she and her co-workers had just spent months working on a large order of hoodies for Old Navy. She told me they had to complete 120 to 150 pieces an hour, every hour, for 14 hours a day, until the order was complete. A soft-spoken 20-year-old man described the production pressure as “inhumane.” The women explained that if they came up short on their hourly targets — which, she said, they often did — they were verbally abused, publicly humiliated, or docked pay. Some supervisors, coaxing women to meet their targets, would touch them inappropriately. “We didn’t even have time to use the restroom because we had to meet our quota,” another woman said.

Bangladesh’s monthly minimum wage in the garment sector, for 8 hours of work, six days a week, is $66, and nowhere near a living wage — which the Asia Floor Wage Alliance, a group advocating a common living wage across Asia, has calculated as $367 a month for Bangladesh. But when I asked these workers how much they had made from all the overtime they put in on the Old Navy order, they laughed. Most had only been paid the standard two hours of overtime a day, which, they explained, they worked on a regular basis, just to cover the rapidly rising cost of rent and other expenses. Despite annual inflationas high as 8 percent in recent years, the minimum wage has gone up only three times in the past decade — each time after worker uprisings and street protests shut down production in manufacturing hubs like Ashulia.

Fed up with the overwork, the low wages, and the disrespect, some of the Ayesha Clothing workers tried to form a union last year. “I realized I am owed much more than I am getting,” one of the men who was a central part of the union effort — I’ll call him Z — told me. Z recruited 250 of his co-workers, of more than 3,000 at the factory, telling them they had a right to organize and needed to “raise their voices to raise their wages.” But the management threatened him, he said, and then one day, the factory fired 70 other organizers without any warning.

Late one night, I visited the working-class neighborhood of Mogh Bazaar in southern Dhaka to meet a group of workers who had tried to organize at another Palmal Group factory. After walking through a maze of narrowing lanes and rows of chicken shops, my translator and I ducked into a dimly lit building with dozens of single rooms, each no larger than 10 feet square and home to a family of workers. Sixteen women — all of whom had worked at a factory called Dacca Dyeing Garments Ltd. for more than a decade — were piled onto a small bed that occupied half the room where one of the women, Reena Begum, lived with her husband and two children. Speaking over one another and finishing each other’s sentences, the women explained why they had decided to form a union: They wanted to able to take sick days without losing pay and take the full four months of maternity leave guaranteed by law. They wanted an end to forced overtime without pay and to their supervisors’ relentless verbal abuse and humiliation. All of these abuses are against the law, at least on paper. When buyers for a brand visited, the workers said, they were instructed to say that they finished work at 5 p.m., even though most routinely had to work till 11 p.m. They wanted to be treated with dignity, they said.

When I asked who these visiting buyers were, several replied in unison: Gap.

Sritee Akter, heavily pregnant and seated at the center of the bed, is a fiery organizer who led the unionizing effort as head of a small group called the Garments Workers Solidarity Federation. A former garment worker who says she entered the industry as an 11-year-old child making clothes for Walmart for roughly $6 a month, Sritee explained that between March and October of 2015, they tried to register a union three times with the government agency overseeing labor relations, the Joint Directorate of Labor. (Walmart has said it has “no tolerance” for forced child labor in its supply chain.) Each time, they were rejected, even though more than half of the nearly 1,000 employees had signed onto the union, well above the law’s 30 percent minimum, according to the Solidarity Center, an international labor group allied with the AFL-CIO. Sritee told me an official at the agency told her quite plainly to stop trying, that the union would be rejected “even if they submitted the application a hundred times.”

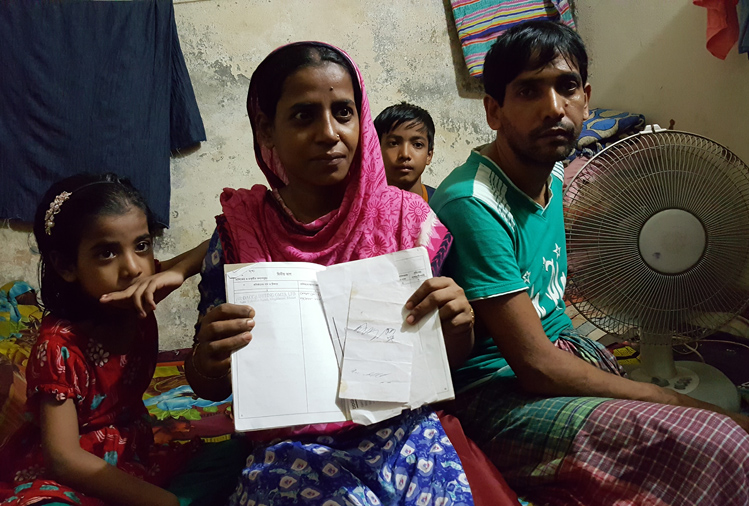

Reena Begum and her family in their one-room apartment in Dhaka's Mogh Bazaar. She's holding up her employment papers from the 13 years she spent at The Dacca Dyeing Garments Ltd.Image: ANJALI KAMAT

The 2013 labor-law reforms had eliminated a requirement that the Joint Directorate turn over to the employer the list of worker signatories filed with the registration application. Yet each time Sritee tried to register, the pressure on workers who had signed on started to rise. The women said their conversations on factory premises were often monitored and their overtime pay was docked. Their individual production targets, they said, were nearly doubled, from 80 pieces an hour to 150. “It was impossible for me to keep up,” Reena told me. Sritee suspects that investigators at the Joint Directorate had shared the list of signatories with factory management, triggering the harassment. Throughout this period, Sritee said she had kept Gap’s Bangladesh office in Dhaka appraised of the situation. “Initially [they] were supportive, but ultimately we didn’t get any help,” she said. Neither the Joint Directorate of Labor nor the Bangladesh Gap office responded to requests for comment.

The pressure on Sritee was also rising. She said she often had to avoid her office and the factory because of threats from thugs hired by the factory management. “Factory owners will band together to push back against anything that threatens their bottom line, and most will stop at nothing to shut down union activity,” she told me. She says she’s been jailed more than once for organizing demonstrations to demand higher pay. In 2009, a local tough outside a factory that she was trying to organize shoved a pistol inside her mouth. In 2014, she went into hiding after the owner of another factory sent 20 men to her office. Sritee nurtures few illusions about the garment business, but said she still called and wrote to the Gap office in Dhaka multiple times asking for support — support, she said, that never materialized. “There’s no security for us organizers,” she said, recalling the brutal murder of labor activist Aminul Islam in April 2012. “We have to live with the possibility that any day someone can come to our doors and hack us to death.”

On Nov. 3, 2015, flanks of police entered the Dacca Dyeing plant as managers terminated more than 150 workers, almost all of whom had expressed support for the union. Wazifa Begum, who lost her job that day, recalled that they were escorted out of the building so quickly, they didn’t even have time to collect their shoes. Sritee, desperate to get the workers reinstated, phoned Gap again to request help, but was told, she recalled, that this was a government matter. Four days later, according to the Solidarity Center, the factory locked its gates — for good.

In their fight for justice, everyone had lost their jobs. Since then, former workers say, almost no one has been able to find a job in another garment factory, not once potential employers find out they used to work at Dacca Dyeing. Reena Begum, who hosted the meeting in her family’s room in Mogh Bazaar, is now a domestic worker juggling two jobs for substantially less pay. “I made clothes for Gap for 13 years,” Reena lamented. “Now I can’t find work as a seamstress anymore, all because I tried to join the union.”

Alonzo Suson, director of the Solidarity Center’s Bangladesh program, told me that supervisors at Dacca Dyeing had told his office they were moving Gap’s orders to another Palmal Group factory because of the unionization drive. “Closing down the factory in this case was simply part of union avoidance,” he said. “Unless the brands get involved and intervene with their suppliers, there’s no other scope for redress.”

The Palmal Group, owners of both Ayesha Clothing and Dacca Dyeing, did not respond to repeated queries.

Gap’s Code of Conduct specifies that its suppliers must respect workers’ freedom of association. The company’s “global sustainability” program claims on its website to be making strides toward ensuring factory safety and pushing suppliers to treat workers with “fairness, dignity, and respect.” In response to queries about labor-law violations at Ayesha Clothing and Dacca Dyeing, Gap spokesperson Laura Wilkerson said by email that the “allegations are wholly unacceptable” and that Gap was reassessing Ayesha Clothing. She added that Gap has been working with the Palmal Group to “bring down the levels of excessive overtime” and had reduced its volume of orders. Gap, Wilkerson said, has sought to ensure that the Palmal Group has a “clear understanding that in order to keep our business, they must take actions to remediate these issues.” She did not specify a timeline for the remediations.

It’s Black Friday in New York City, the busiest shopping day of the year. The sidewalks around Manhattan’s historic Garment District are tightly packed with shoppers searching for the best holiday bargain, slowly moving between the retail stores lining the block: H&M, Zara, Old Navy, Macy’s, Gap. I enter a Gap store on West 34th Street, and in the space of half an hour at least two dozen sales associates stop me with a warm smile and ask if I need help. I ask how long they have been working. Exhaustion spreads over their faces. The store opened the day before, on Thanksgiving, and had yet to close.

Everything in the store today is 50 percent off, which brings the price of a boys’ T-shirt to less than $5 and a pair of boys’ jeans to under $20. It is hard to imagine how, with prices that low, Gap is able to pay its suppliers rates that would allow them to offer Bangladeshi seamstresses the overtime and sick pay they are due.

Most of the sales associates are nervous about talking to a reporter, but a few agree to some quick questions if I don’t use their names — and their managers are out of sight. Despite the long hours they’re working today, their biggest concern, they tell me as I look through a selection of Gap Kids sleep T-shirts for $12.50, is not getting enough hours of work. Most of them say they make $11 or $12 an hour and aren’t guaranteed more than 25 hours a week. “If I’m lucky, I get 30,” one woman tells me. “The only time we get a lot of hours is on busy days like this — we go from four- to five-hour shifts to eight- to nine-hour shifts.” Almost everyone they know at the store has to work a second part-time job just to survive. “It’s a matter of scraping by,” an older woman with grandchildren says, before quickly going back to folding clothes.

Earlier in the day I had shadowed the Retail Action Project and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union as they marched through midtown Manhattan for a Black Friday protest, chanting loudly against union busting and poverty wages. I met a young woman from Harlem who was fired from Gap in September, for tardiness and excessive sick days, after working at one of their Manhattan stores for a year. Jennifer Osula told me that what frustrated her the most, besides the low pay, was that as a part-time employee, she simply couldn’t get enough hours to qualify for sick leave when she needed to. “I was just tired of it. They didn’t want to give us long shifts but would suddenly make us do overtime without any warning. We couldn’t plan for anything.” It was as if the axes of exploitation had been inverted: In Bangladesh, women were working so many hours they barely had time to sleep; here employees are starving for more. What they shared was a lack of access to sick leave and a living wage.

Part-time work without benefits and with unpredictable schedules has come to define the working lives of most retail workers across the country. Brands like Gap now typically use software to determine hourly staffing needs based on sales and store traffic, aiming to have fewer staff during lean periods and more during peak hours, resulting in short shifts, and irregular ones. According to a study by the Retail Action Project and the CUNY Murphy Institute in 2012, only 17 percent of New York City retail workers surveyed had a fixed schedule.

Last year, six brands, including Gap, announced that they would stop using on-call shifts after an inquiry by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman into the practice. But Rachel Laforest, director of the Retail Action Project, says compliance appears to be uneven. “Absent legislation like a Retail Worker’s Bill of Rights,” she says, “enforcing an end to on-call could come down to individual managers at different stores.”

Gap’s Wilkerson said by email that the company offers both full- and part-time positions and has partnered with the University of Chicago and Hastings College of Law at the University of California to “evaluate its scheduling practices.”

- “[Buyers] are still looking for the cheapest labor. If they find it cheaper in Cambodia or Ethiopia, they will go there. It's just that simple.”

Mark Anner, a political scientist at Penn State, argues that the advent of fast fashion has led to a steady decline in labor rights. With the rise of “just in time” production, in which producing decisions are determined in real time by consumer demand, buyers are giving factories less and less lead time to complete orders, creating a culture of chronic overtime. In 2011, Anner found that major global brands gave Bangladeshi factories an average of 94 days to complete an order. So far in 2016, it’s down to 86 days.

In addition, Anner argues, trade liberalization and retail consolidation have driven a race to the bottom on prices. The price drop is “significant and sustained,” he told me, explaining how the price of Bangladesh’s major apparel export to the U.S., cotton trousers, has dropped by 46 percent since 2000. At least 9 percent of that drop took place after the Rana Plaza collapse.

“It doesn’t help to tell the buyers that we have safe factories now,” says Huda, the factory owner, back in Ashulia. “They are still looking for the cheapest labor. If they find it cheaper in Cambodia or Ethiopia, they will go there. It’s just that simple.”

Factories are left, he said, pushing for ever more productivity from the workers, without the ability to raise wages. Daily production charts drawn up on boards on every floor of his factory listed the hourly performance of each worker. The targets, based on the performance of the fastest workers, were as high as 195 pieces an hour. “We are at 82 percent” in hitting production targets, he said. “The goal is 100 percent.”

The Grind is a yearlong series looking at the unsavory — and often hidden — working conditions behind some of our cherished annual traditions. It is a collaboration with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations.