For its first FDA-authorized human trial, which began in 1998, Conceptus kept the basic design but altered the metal coils to prevent them from moving, the 2004 paper explains. For its outer, ribbonlike coil, it chose a relatively new material in the medical device arena called Nitinol, which had been developed at the now-closed Naval Ordnance Laboratory in Silver Spring, Md. (coincidentally, the current location of the FDA). Nitinol, a flexible nickel-titanium “shape memory” alloy, as it is known, can be set to take a shape at a certain temperature, relax at a lower temperature and bounce back once warmed up again. For Essure, shape memory meant that the coils could be packed tightly in a slim delivery catheter. Once they hit body temperature, they would expand, allowing the PET fibers in the device to incite the “acute inflammation followed by chronic inflammation” that would generate the scar tissue and block the tubes, according to the 2004 paper.

While Nitinol had been used in medical devices since the 1980s, there were already published reports of failures with cardiovascular stents made of the material and of patients developing reactions to metal implants in general. According to Peter Schalock, a Boston-area dermatologist who has published extensively on metal hypersensitivity, reactions to implanted devices can include rashes or eczema, chronic inflammation and chronic pain, all of which are among the adverse events reported by Essure women.

Schalock and several experts in immunology or toxicology expressed concern at the 2015 FDA hearing that the nickel in Essure could be triggering allergic or autoimmune reactions, in which the immune system overreacts and attacks healthy cells. In addition to the issue of nickel, he and other physicians have raised concerns about the PET fibers used to incite the inflammatory response: “Maybe the inflammatory state goes a little wild,” Schalock told me. “The question is what’s driving it. Is it the Essure, or is the Essure waking up some sort of predisposition to autoimmune disease?”

I raised these questions with Bayer, which purchased Conceptus in 2013 for $1.1 billion. The company acknowledged in an email from its communications office that “a small amount of nickel is released from Essure” and said it would continue to analyze complaints about nickel sensitivity. Patricia Carney of Bayer says that tests for leaching in Phase I trials concluded that “the amount of nickel that comes out of the Essure inserts is actually far less than what comes out of most of the nickel-containing devices that are on the market.” In response to the possibility that the device could be causing autoimmune reactions, Carney points out that autoimmune disease is already common in women. “What we then have to tease out is why are women having these symptoms,” she says. “Because they’re happening in women both with Essure and without Essure.”

Melissa Davis-Gilbert talks with her husband, Dan, before a hysterectomy to remove her Essure coils. Davis-Gilbert, a nurse from Havre de Grace, Md., had originally opted for Essure about a decade ago to avoid surgery. She says that after experiencing pain, fatigue, rashes, joint swelling, difficulty concentrating and respiratory issues, she decided to have the device removed.Image: KATHERINE FREY/WASHINGTON POST MAGAZINE

Before selling Essure to the public, Conceptus had to submit the device to scientific and regulatory review by the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. The Center, which was established in 1976 in the wake of the crisis over the Dalkon Shield — an intrauterine device that caused several deaths and generated thousands of lawsuits because of its design, materials and lack of testing — has different requirements for approval of medical devices than the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, which reviews drugs. “The legal standard for approving a drug explicitly requires adequate and well-controlled clinical investigations,” says Patricia Zettler, former associate chief counsel for the FDA, who now teaches food and drug law at Georgia State University. In contrast, for devices, the standard is “reasonable assurance” of safety and effectiveness, she says, which is subject to interpretation.

Conceptus applied for approval of Essure in the category of Class III medical devices, which, according to the FDA, “are generally the highest risk devices and are therefore subject to the highest level of regulatory control.” This class goes through the most rigorous application process for devices, known as premarket approval. But it is also the only class of device shielded from most lawsuits, thanks to a 2008 Supreme Court decision that makes it difficult for patients to sue in state court for devices that have received premarket approval. In addition, the FDA granted Essure expedited review, a legacy of AIDS activism intended to speed access to potentially lifesaving therapies, in which the FDA puts a treatment at the beginning of a review queue and provides advice on clinical trial design. The FDA fast-tracked Essure, it said, “because this device offers significant advantages over existing approved alternatives.”

Although Class III devices are protected from most lawsuits and undergo the most rigorous approval process, they are not required to undergo randomized controlled trials — in which one randomly assigned group of patients gets the treatment, another group gets a different treatment, and the outcomes are compared. The FDA said in a written statement to me that it did not believe a control group was necessary for Essure because, at the time, “effectiveness and safety outcomes for laparoscopic tubal ligation were well known from years of clinical use” and could be used for comparison. Sanket Dhruva, a Yale University cardiologist and researcher of high-risk medical devices, strongly disagrees. “We all know the most rigorous data in clinical medicine is through randomization,” control groups and follow-through, he says. Ideally, he explains, the researchers would have given 1,000 women Essure and another 1,000 women laparoscopic sterilization and followed them for five years to compare rates of pregnancy, complications, hysterectomy and repeat surgeries. Without a real-time comparison, he says, “we just didn’t have the data.”

For its third, “pivotal” trial, the most important for achieving approval, Conceptus reported on 439 women. None of the women became pregnant, for an effectiveness rate of 100 percent — though Conceptus noted that “no method of contraception is 100% effective, and pregnancies are expected to occur in the commercial setting.” The company compared this to a long-term study of 10,000 women who elected tubal ligations, which found a rate of pregnancy of 5.5 per 1,000 for the first year. A “serious adverse event” — in which the Essure device perforated the fallopian tube, was expelled or wasn’t placed correctly — occurred in 4.6 percent of participants. After one year of use, according to the data, 9 percent of women reported back pain, 3.8 percent reported abdominal pain and cramps, and 3.6 percent reported painful sexual intercourse.

When asked if this was an acceptable number of adverse events, the FDA said in its response to me that Conceptus demonstrated “reasonable assurance that the device is safe and effective for its intended use.” It went on to explain: “In determining safety and effectiveness, the FDA weighs any probable benefit to health from the use of the device against any potential risk of injury or illness from such use.” One important benefit, according to the FDA, as well as many doctors and researchers, was that women seeking permanent sterilization could avoid surgery by opting for Essure. (It has been estimated that there are about four deaths per 100,000 surgical sterilizations, and a complication rate — involving bleeding, infection, organ damage or anesthesia reaction — of 1.6 percent.)

The fact that Conceptus had only followed the women for one year — the company itself noted that “the risks of long-term implantation [of Essure] are unknown” — also troubled Dhruva. A short-term study “might be okay if it’s a medication that you take for a week,” he says. “But we’re talking about a device that’s going to be implanted in a million people for the rest of their lives.”

In order to monitor any potential long-term effects of the device, one of the FDA’s conditions in approving Essure under expedited review was that the company would continue to follow the women from the pivotal study for at least five years. That data, which was submitted in 2008 but not posted by the FDA until 2014, reported that 92 percent of the 384 participants said overall comfort was “excellent” and 97 percent said they were “very satisfied.” But the company noted that 30 percent of the original study group could not be followed for the full five years. This was yet another weakness of the studies, says Dhruva, because if those women had a complication or got pregnant, the outcomes wouldn’t be reflected in the results.

Looking back on Essure’s clinical trials, Dhruva and two other Yale-based physician researchers took the FDA to task in a 2015 opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, citing the “large numbers” of adverse events reported since the device went on the market, such as incomplete procedures, tubal perforations, pain and bleeding leading to hysterectomies, possible device-related deaths and likely a higher number of unintended pregnancies than previously disclosed. “We believe that these safety concerns, along with problems with the device’s effectiveness, might have been detected sooner or avoided altogether if there had been higher-quality premarketing and postmarketing evaluations and more timely and transparent dissemination of study results,” wrote Dhruva, Joseph S. Ross and Aileen M. Gariepy. When asked, the FDA declined to respond to the article. A Bayer representative said, “We disagree with many of the assertions in this article and remain confident that the benefits of Essure outweigh its risks.”

Dhruva, who has been researching high-risk devices for nearly a decade, says the Essure case is just one example of “substandard data” used for device approval. “And unfortunately,” he says, “I think a lot of women have suffered from consequences.”

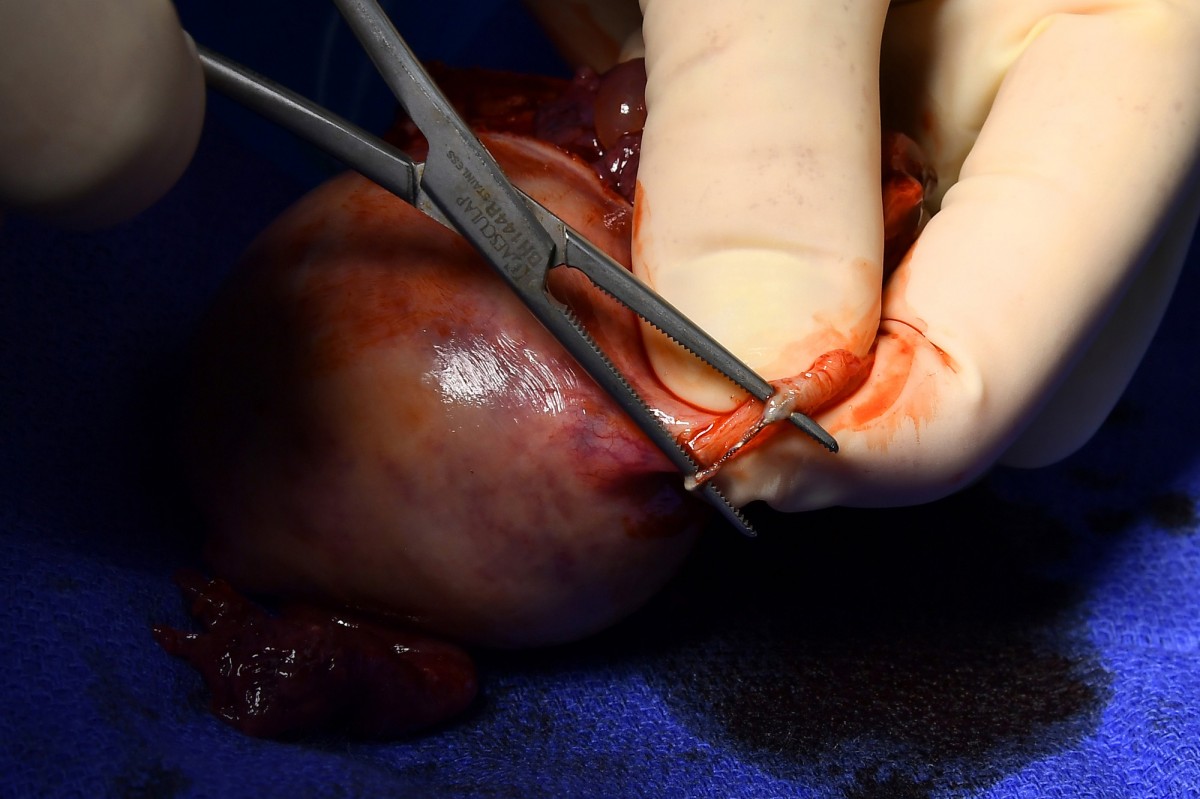

OB/GYN Paul MacKoul performs a hysterectomy on Melissa Davis- Gilbert to remove Essure coils, shown adhering to a fallopian tube. Scrub nurse Karen Ricupero, first assistant Tito Fernandez and MacKoul during the surgery. These photos, and the one above, were taken, and are being published, with the consent of the patient and medical staff.Image: KATHERINE FREY/WASHINGTON POST MAGAZINE

After its approval, Essure was welcomed with open arms by the women’s health community, which had been seeking an alternative to surgical tubal ligation — at that time the most common form of contraception for women over the age of 40. In 2002, “the availability of an easier, faster, safer sterilization technique” was a big advance, says Cindy Pearson, executive director of the National Women’s Health Network. This enthusiasm extended to physicians as well, and many became early adopters of Essure. “I saw it as a game-changer with respect to female sterilization,” says James Robinson, a gynecologic surgeon at MedStar Washington Hospital Center. He estimates that he implanted hundreds of the devices in the decade he served as an OB/GYN with George Washington University Medical Center and says he never had patients return with complaints.

Other factors might also have influenced doctors’ enthusiasm for Essure. For one thing, it takes less time to implant the device than to perform tubal ligation surgery in a hospital. Then there are the reimbursement rates. In 2011 documents created by Conceptus for its sales team, the company estimated that a doctor who inserted 60 Essure devices a year would net $66,747.78, or slightly more than $1,100 per device. By contrast, a physician is reimbursed about $510 by private insurance for surgical sterilization in a hospital, according to Amino, a company that uses U.S. insurance claims data to help consumers estimate health-care costs.

Barbara Levy, vice president of health policy at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and a former consultant to Conceptus, says the higher reimbursement rate is meant to cover office overhead and the equipment necessary to insert Essure, not to serve as an incentive for doctors to recommend Essure over tubal ligation. But Robinson argues that the rate does present an incentive, “and it’s supposed to.” He believes that the idea behind the Essure reimbursement rate is to steer doctors away from the more costly hospital-based procedure.

The problem with a procedure that reimburses well, Robinson contends, “is that everybody jumps onboard: ‘Oh, I’m going to do Essures and I’m going to pay my kids’ college tuition.’ ” But Essure isn’t appropriate for every woman, he says, and should be inserted only by doctors who understand and can manage the risks.

RW Carney watches as four of his children — from left, Malik, Khalil, Mekhi and Brianna — play with Diggy the dog. Mekhi was born after Keisha had the Essure devices implanted.Image: KATHERINE FREY/WASHINGTON POST MAGAZINE

Like many of the women I spoke to, Angie Firmalino, 45, says that her doctor recommended Essure. Shortly after her 2009 procedure, which she says was excruciating, the Tannersville, N.Y., woman began having constant bleeding and pain. She developed joint problems that she attributes to an autoimmune response and had to have surgery to remove the coils. The operation left fragments behind and resulted in a hysterectomy. She’s still dealing with chronic pain, muscle weakness and blood circulation problems, which she also thinks are autoimmune related.

In 2011, Firmalino decided to start a group on Facebook to share her experiences with female friends. Then, strangers started requesting to join and “telling their horror stories, some worse than mine,” she says. Soon the Essure Problems group had hundreds, then thousands of women. They wrote graphic descriptions of their pain and blood loss, fatigue and weight gain; they posted pictures of their thinning hair and bloated bellies that could be mistaken for marking the weeks of pregnancy. And they shared the stranger symptoms: joint pain, sudden muscle weakness, skin rashes. “That’s when the talk started about what is this device made out of?” Firmalino says. “Then we discovered there’s nickel in the device. None of us knew.”

The handful of women administering the group began researching the device and submitting requests for federal records. One of the details that disturbed them was that the Conceptus vice president who presented the application to the Center for Devices’ OB/GYN devices advisory panel, Cindy Domecus, had been an industry representative on that same panel from 1995 to 2001. In 2002, when Domecus appeared before the panel on behalf of Essure, four of the panel’s nine voting members, including the chairman, were people she had served with. (Domecus declined to comment for this article.) When I asked the FDA about Domecus’s tenure on the panel, it noted that industry representatives cannot vote. However, Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research, which scrutinizes industry influence in health care, believes sitting on the panel gives industry members advantages by allowing them to build relationships and gain “a better understanding of how to influence the vote.”

Another concern for the women involved the nickel. The 2002 package label listed nickel allergy as a “contraindication” (meaning the device should not be used for patients with that condition) and included a directive that physicians screen patients for the allergy. The women learned, however, that in 2011 the FDA granted a Conceptus request that the contraindication be downgraded to a “warning,” which doesn’t require physicians to screen patients. (The current labeling includes a nickel warning. The FDA told me it used a warning rather than a contraindication because it “concluded that the data did not meet the threshold of known hazard.”)

Yet another issue the Essure Problems administrators believe got short shrift was removal of the device. A Conceptus representative testified at the 2002 hearing that taking it out would require cornual resection — removing the area where the fallopian tubes meet the uterus. But doctors have since found that’s “not easy,” says Myron Luthringer, a Syracuse, N.Y., OB/GYN who says he has removed hundreds of the devices. He explains that the coils are fragile and break apart, that the tissue in that area is difficult to repair and that PET fibers have often embedded in the surrounding tissue. For those reasons, he says, he tends to perform a hysterectomy, removing the uterus and cervix, as well as the fallopian tubes. Other physicians do as well. “We really advocate that the right procedure is hysterectomy,” says Paul MacKoul, an OB/GYN at the Center for Innovative Gyn Care in Rockville. But hysterectomy — and cornual resection, for that matter — require the very element many women who chose Essure were trying to avoid: surgery with anesthesia. “Anything that’s designed to be permanent is very difficult to take out,” notes MacKoul’s partner and fellow OB/GYN, Natalya Danilyants.