On nights when the November rain poured down and he had not slept at all, Jhonny Arcentales had visions of dying, of his body being cast into the dark ocean. He would imagine his wife and their teenage son tossing his clothes into a pit in a cemetery and gathering at the local church for his funeral. It had been more than two months since Arcentales, a 40-year-old fisherman from Ecuador’s central coast, left home, telling his wife he would return in five days. A cuff clamped onto his ankle kept him shackled to a cable along the deck of the ship but for the occasional trip, guarded by a sailor, to defecate into a bucket. Most of the time, he couldn’t move more than an arm’s length in either direction without jostling the next shackled man. “The sea used to be freedom,” he told me. But on the ship, “it was the opposite. Like a prison in the open ocean.”

By day Arcentales would stand against the wall and stare out at the water, his mind blank one moment, the next racing with thoughts of his wife and their newborn son. He had not spoken to his family, though he asked each day to call home. He increasingly felt panicked, fearing his wife would believe he was dead.

Arcentales has wide muscular shoulders from his 25 years hauling fishing nets from the sea. But his meals now consisted of a handful of rice and beans, and he could feel his body shrinking from the undernourishment and immobility. “The moment we would stand up, we would get nauseated, our heads would spin,” he recalled. The 20-some prisoners aboard the vessel — Ecuadorians, Guatemalans and Colombians — would often stand through the night, their backs aching, their bodies frigid from the wind and rain, waiting for the morning sun to rise and dry them.

In the first weeks, Arcentales had turned to his friend Carlos Quijije, another fisherman from the small town of Jaramijó, to calm him. They were chained side by side, and the 26-year-old would offer some perspective. “Relax brother, everything is going to work out,” Arcentales remembered Quijije saying. “They’ll take us to Ecuador, and we will see our families.” But after two months of being shackled aboard the ship, Quijije seemed just as despondent. They often thought they would simply disappear.

By this time it was November 2014, and in the brick box of a house where Arcentales lived in Ecuador, Lorena Mendoza, Arcentales’s wife, and their children were praying together for his return. In Jaramijó, it is not unheard-of for fishermen to vanish, stranded by a broken motor, shot by a pirate or shipwrecked in a storm. “I was always worried that we would never see him again,” she told me. “But he always came home.” This time Mendoza was certain she would receive a call to collect Arcentales’s waterlogged body from the docks.

Mendoza had no way of knowing that her husband was still alive. He had departed Jaramijó because his family needed money so desperately that he had accepted a job smuggling cocaine off the coast of Ecuador. But deep in the Pacific, Arcentales and the other fishermen he traveled with were stopped not by pirates or vigilantes but by the United States Coast Guard, deployed more than 2,000 miles from U.S. shores to trawl for Andean cocaine. Over the past six years, more than 2,700 men like Arcentales have been taken from boats suspected of smuggling Colombian cocaine to Central America, to be carried around the ocean for weeks or months as the American ships continue their patrols. These fishermen-turned-smugglers are caught in international waters, or in foreign seas, and often have little or no understanding of where the drugs aboard their boats are ultimately bound. Yet nearly all of these boatmen are now carted from the Pacific and delivered to the United States to face criminal charges here, in what amounts to a vast extraterritorial exertion of American legal might.

The U.S. Coast Guard never intended to operate a fleet of “floating Guantánamos,” as a former Coast Guard lawyer put it to me in May. The Coast Guard has a humanitarian public image, celebrated in local newspapers for rescuing pleasure boaters off Montauk or hurricane survivors in Florida. But as the lone branch of the military that serves as a law-enforcement agency, the 227-year-old service has also long been in the business of interdicting contraband, from Chinese opium smugglers to Prohibition rumrunners. For centuries, Coast Guard operations waited to arrest smugglers once they crossed into U.S. territorial waters. Then, in the 1970s, as marijuana trafficking ballooned on the route from Colombia into the Caribbean before arriving in the United States, Justice Department officials argued to Congress that current U.S. law constrained law enforcement’s ability to punish drug smugglers caught on the high seas. While the Coast Guard, then a branch of the Department of Transportation, could chase smugglers into the Caribbean, Justice Department lawyers could rarely hold smugglers caught in the legal gray zone of international waters criminally liable in U.S. courts.

Congress responded by passing a set of laws, including the 1986 Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act, that defined drug smuggling in international waters as a crime against the United States, even when there was no proof that the drugs, often carried on foreign boats, were bound for the United States. The Coast Guard was conscripted as the agency empowered to seek out suspected smugglers and bring them to American courts.

In the 1990s and through the 2000s, maritime detentions averaged around 200 a year. Then in 2012, the Department of Defense’s Southern Command, tasked with leading the war on drugs in the Americas, launched a multinational military campaign called Operation Martillo, or “hammer.” The goal was to shut down smuggling routes in the waters between South and Central America, stopping large shipments of cocaine carried on speedboats thousands of miles from the United States, long before they could be broken down and carried over land into Mexico and then into the United States. In 2016, under the Southern Command’s strategy, the Coast Guard, with intermittent help from the U.S. Navy and international partners, detained 585 suspected drug smugglers, mostly in international waters. That year, 80 percent of these men were taken to the United States to face criminal charges, up from a third of detainees in 2012. In the 12 months that ended in September 2017, the Coast Guard captured more than 700 suspects and chained them aboard American ships.

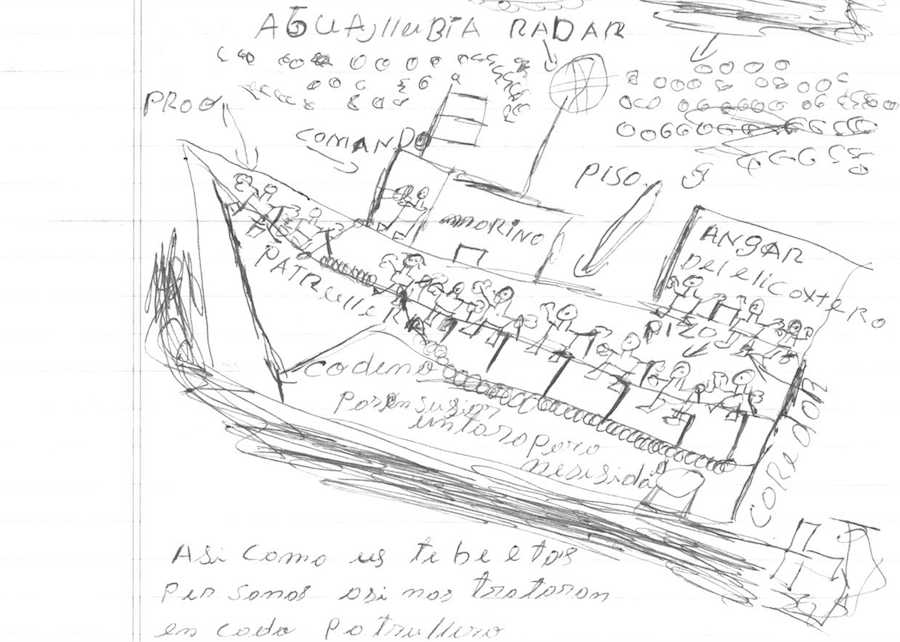

A drawing by a man who was detained on a Coast Guard cutter. Several detainees sketched similar images and mailed them in letters from U.S. federal prisons where they are now incarcerated.

Over the last year, I’ve interviewed seven former Coast Guard detainees, some of whom are still in American federal prison, and received detailed letters, some with pencil renderings of the detention ships, from a dozen others. Most of these men remain confounded by their capture by the Americans, dubious that U.S. officials had the authority to arrest them and to lock them in prison. But it is the memory of their surreal imprisonment at sea that these men say most torments them. Together with thousands of pages of court records and interviews with current and former Coast Guard officers, these detainees paint a grim picture of the conditions of their extended capture on ships deployed in the extraterritorial war on drugs.

Their protracted detention is justified by Coast Guard officials and federal prosecutors alike, who argue that suspects like Arcentales are not formally under arrest when the Coast Guard detains them. While on board, they’re not read Miranda rights, not appointed lawyers, not allowed to contact their consulate or their families. They don’t appear to benefit from federal rules of criminal procedure that require that criminal suspects arrested outside the United States be presented before a judge “without unnecessary delay.” It is as if their rights are in suspension during their capture at sea. “It’s hard-wired into the Coast Guard’s minds,” says Eugene R. Fidell, a former Coast Guard lawyer who teaches at Yale Law School, “that usual law enforcement constraints don’t apply.”

The increased detentions and the domestic prosecutions of extraterritorial activity were ushered in largely under the watch of Gen. John Kelly, who from 2012 to 2016 served as the head of the Southern Command and is now the White House chief of staff. He has long championed the idea that drug smuggling and the drug-related violence in Central America poses what he has called an “existential” threat to the United States and that to protect the homeland, American law enforcement must reach beyond U.S. borders. This April, during his brief tenure as Trump’s secretary of Homeland Security, which now oversees the Coast Guard, Kelly gave a lecture at George Washington University. “We are a nation under attack” from transnational criminal networks, he told the audience. “The more we push our borders out, the safer our homeland will be,” he said. “That includes Coast Guard drug interdictions at sea.” Asked about the detainments, a White House spokesperson said, “Under General Kelly’s command, U.S. personnel treated detainees humanely and followed applicable laws.” The spokesperson declined to comment further.

Like most men he grew up with in Jaramijó, Arcentales began fishing as a teenager and never stopped. He often worked with Quijije, who lived with his wife, daughter and his wife’s family in a two-room house just up the hill from Arcentales. After working on their boss’s skiff, they would meet up and talk for hours about their children and their plans to someday buy a boat of their own.

Arcentales never had much money. The $6,000 he could hope to make a year, on the skiff and working on tuna ships for a month or two at a time, does not stretch far in Ecuador’s economy. The house where he and Mendoza lived was just a single room for their family of nine: their teenage son, Enrique; Mendoza’s two older daughters from a previous marriage, Nelly and Juliana, who have three children between them; and Nelly’s husband, Wladimir Jaramillo. They all slept on fraying mattresses, sharing a single toilet. When it rained, the roof leaked and muddy water trickled through the door.

The thrum of anxiety about money became an alarm in 2014 when Mendoza unexpectedly became pregnant at 43. A doctor prescribed bed rest. Too worried to be out at sea for long, Arcentales worked less. That July, Mendoza gave birth to a boy they named Ismael. The household had grown to 10. It would be more than two months before his next fishing trip, and Arcentales could not escape the nagging sense of failure. “I would lie some nights in bed, asking myself, ‘Am I going to live my entire life in a hut that is close to falling apart?’ ” he said. “ ‘What will I leave my children?’ ”

On the morning of Sept. 5, after a very bad night of sleep, Arcentales left Mendoza and their children. “Viejita,” he told her, “don’t worry, everything will be O.K.” A fisherman Arcentales had known for years had been soliciting Arcentales for two years to accept a cocaine smuggling job. Arcentales always refused. But when he left home that September morning, Arcentales went looking for that man. Ecuador is a secondary shipment point for Colombian drug-smuggling groups who work increasingly for Mexican cartels, and in Jaramijó, recruiters, called enganchadores, those who “hook,” have become fixtures. Residents of the town have watched as their neighbors return from what they say were fishing trips, then buy cars or fix up their homes. Residents call the trip “la vuelta,” which means, aspirationally, “round trip.” The fisherman told Arcentales that he would earn $2,000 up front, and then $20,000 apiece for him and his partner upon their return. It was as much as Arcentales could expect to earn in three or four years. If Quijije joined him, they could finally buy their boat.

The next evening, he and Quijije met another man in San Lorenzo, near the Colombian border. The man led them to a skiff, gave Arcentales a GPS tracker and instructed the pair to meet another boat at a location 50 nautical miles away. There, he said, they would collect 100 kilos of cocaine, split in four packages, and the coordinates for another vessel less than a day’s trip away where they would drop off the drugs and then be done. But when they arrived at the location to retrieve the drugs, they were instead given 440 kilos of cocaine and joined by a baby-faced Colombian in his early 20s named Jair Guevara Payan, paid to watch the drugs. Payan led Arcentales and Quijije on a five-day voyage, 1,100 miles to the north, farther than either man had ever ventured. Arcentales considered refusing to go, but he knew there was no real choice now that they were at sea. “We had been screwed,” he told me.

When Arcentales, Quijije and Payan finally arrived at their final coordinates, 145 miles off the coast of Guatemala, a small white speedboat motored toward them, then another, each manned by two Guatemalan men. Together, the men offloaded the drugs onto one of the boats, and Payan motored away on it with a pair of Guatemalan brothers. Arcentales and Quijije were told to step into the second boat, a skiff called the Yeny Arg, manned by the two other Guatemalans, Giezi Zamora, a mechanic, and Hector Castillo, a fisherman. The four of them headed for shore, and Arcentales let his senses dull for the first time since he had set out. “We are free,” he thought to himself, and nearly fell asleep.

- “I would lie some nights in bed, asking myself, ‘Am I going to live my entire life in a hut that is close to falling apart?’ ”

But a U.S. Navy patrol airplane had been tracking the Guatemalan boats since the morning. The plane’s crew had watched the men step into the arriving boats and the Southern Command had contacted the Coast Guard. Soon, Arcentales spotted a white military ship, then a speedboat with five officers aboard racing toward them. The officers ordered Arcentales and the others not to move, and the men raised their hands in the air.

When boats are not registered to a country or flying a country’s flag, they are considered stateless, and maritime laws allow U.S. officials to board. Hundreds of these unmarked boats depart from Ecuador and Colombia each year. But the Yeny Arg was registered in Guatemala, so federal officials contacted their Guatemalan counterparts to gain permission, under a bilateral agreement, to board and conduct a search. U.S. authorities have some 40 agreements with countries around the world to gain access to foreign vessels. For some countries, U.S. prosecution removes a burden from their own legal systems; with other countries, the U.S. has exerted pressure on governments to forge such agreements. Countries in the Americas and the Caribbean have generally allowed U.S. officials to board and search ships that bear their flags.

For several hours, the Coast Guard officers searched the Yeny Arg. By midafternoon, Arcentales, Quijije and the two Guatamalans were moved to the Coast Guard speedboat, and were delivered to the Coast Guard ship. On board, they had mug shots taken. Less than 12 hours later, the men were moved to a Coast Guard ship called the Boutwell, a 378-foot, 46-year-old cutter with a crew of 160. Payan and the Guatemalan brothers were already onboard.

The men were not told where they would be taken nor allowed to call their families. Officials told them to strip down and change into papery white Tyvek jump suits, and then guards led them up a flight of stairs above the deck and into a hangar. Arcentales felt a cuff close around his ankle. He and Quijije looked at each other, and then at their ankles, which, he said, were now attached to the floor by short chains. Thin rubber mats would serve as their beds. “A deep sadness came over me,” Arcentales said. “Right there my life changed.”

On the Boutwell, Arcentales and the other men began asking the guards where they were being taken. One Spanish-speaking guard explained to the men that American officials were coordinating with officials from his country to arrange a transfer. The guard, Arcentales said, told him they would be on land in five days. Several nights passed on the Boutwell. Then, as the sun rose on the fifth day, the men spotted land. They could make out a volcano, then a port — the topology of Central America. “We thought we were going back to our country,” Arcentales said. “We thought they were going to hand us over to migration. Migration or the Ecuadorean consulate.”

But as they approached land, a guard showed up with a plastic bucket to use as a toilet. An officer closed the doors of the hangar where they were held. Through small holes in the wall, they could see people walking on the docks. The Guatemalans recognized a port called Acajutla. An hour passed, then four, then eight. When the narrow beams of light that had shone through the holes in the hangar wall faded, they felt the Boutwell move. The boat’s engines roared, and a guard threw open the doors: The sun was setting, and the men were back at sea. For 30 minutes, an hour maybe, they sat in silence, watching the water and the sky become dark, their minds turning to their families. That night, Arcentales and Castillo, the Guatemalan fisherman, both cried, their chests heaving as the other men looked out at the sea.

When the sun rose the next morning, the men took notice of each other not as they had before, as accidental fellow prisoners, but as longer-term companions. Castillo, who was just shy of 24, asked Arcentales, whom he called “Don Jhonny” out of his respect for his age, about his family. They learned that Zamora, Quijije and Arcentales were fathers of newborns, or had a child on the way. “We would talk of our young kids,” Arcentales said about conversations the men had. “And then there were days when I would not say a word. I would just stay in my mind thinking of my kids, my baby, my failure.” They had all accepted what they thought was the remote risk of arrest in order to provide for their family. Castillo said that he had already taken la vuelta two weeks before. It had been relatively easy, so he’d taken another. “You start to think you can get away with it,” Castillo told me.

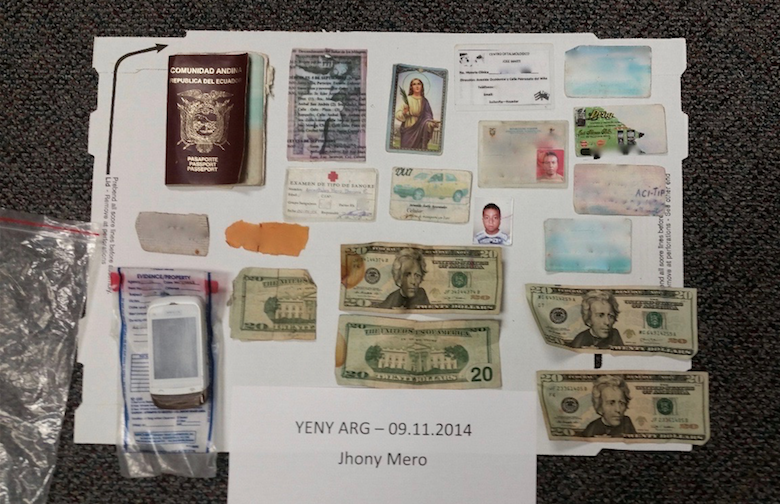

The things Jhonny brought with him on his smuggling trip, including a photograph of his son, Enrique, an image of the Virgen and a passport. This photo has been altered to preserve

Jhonny's privacy. Image: FEDERAL COURT CASE RECORDS

Coast Guard and Southern Command officials, including John Kelly, have argued that if the agency had more ships to deploy, it could interdict four times as much cocaine. “Because of asset shortfalls, we’re unable to get after 74 percent of suspected maritime drug smuggling,” Kelly said at a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing in 2014. “I simply sit and watch it go by.” Colombian cocaine production is again on the rise, and while the Coast Guard says it has seized nearly half a million pounds of cocaine over the past year, agency officials have warned as recently as this September that they need more resources to stop the flow.

Government officials say intelligence gained from small-time boatmen is key to investigating and dismantling larger transnational criminal networks. The Coast Guard has claimed that between 2002 and 2011, cases against these maritime smugglers helped the government secure three-quarters of its extraditions of Colombian drug kingpins. Affidavits filed more recently in criminal cases against three Mexican and Central American drug leaders, including the notorious cartel leader El Chapo, have noted boat interdictions as small points in larger constellations of evidence. By linking kingpins to boats, prosecutors can add maritime smuggling to the list of charges against them. But the fishermen caught aboard these small smuggling boats, many detained on their first or second run, often have access to mere fragments of information about the people they’re working for. For the most part, men like Arcentales barely know the identity of their recruiter, sometimes just a first name or moniker, and nothing more. “They are not key widgets in this process,” said Bruce Bagley, a leading scholar on drug smuggling and a professor of political science at the University of Miami. By prosecuting them, he added, “you don’t slow down the broader operations.”

On Oct. 6, 25 days after the men were caught, the Boutwell returned to its home port in San Diego. The crew of the ship lined up for photos on the deck behind bales of cocaine wrapped in black tarps, collected from 14 smuggling boats, including, presumably, Payan’s, and worth, according to the Coast Guard, more than $400 million.

The cocaine made land long before the detainees. For 44 more days, Arcentales, Quijije, Payan and the Guatemalans were transferred from one ship to the next, passing a week or 10 days on one, a few days on another, always chained to the decks. “I remember one time I asked the nurse officer if he could do me a favor,” Payan wrote later in a letter, “just shoot me and kill me, I would appreciate, because I cannot take this anymore.” As day after mind-numbing day dragged on, hunger began to rival their families as their central preoccupation. Food logs from Coast Guard ships and testimony from Coast Guard officers show that on some ships, detainees’ meals consisted of only small portions of black beans and rice, on occasion with a bit of spinach or chicken. Arcentales says that he learned to eat slowly, to fool his mind into thinking the plate contained more than it did. The men watched the guards discard their unfinished meals into trash bags hanging nearby and devised a plan. “Someone would ask to be taken to the restroom so that we could try to reach the trash and take the food,” Quijije said in testimony. They would pass a piece of leftover chicken down the line, each detainee taking a bite and handing it to the next, until the bone was picked clean. After more than two months of detention, Arcentales says, he had lost 20 pounds; Payan says he lost 50. Time began to warp for them. “We could no longer endure living in such conditions for that prolonged period of time,” Arcentales wrote later in a letter. “It did not matter to us where they would leave us; we were desperate to communicate with our family.” The Coast Guard and the Department of Justice maintain that all detainees are treated humanely and with accordance to the law. The Coast Guard adds that it shackles detainees and conceals them while in port for their own safety and the safety of the crew.

- "I asked the nurse officer if he could do me a favor . . . . Just shoot me and kill me, I would appreciate, because I cannot take this anymore.”

The Coast Guard does not have discretion over where and when to transfer drug-interdiction detainees. Those decisions are made by the Department of Justice, the D.E.A. and federal prosecutors with information from the Coast Guard. Coast Guard officers I spoke to, one of whom was disturbed enough to call the vessels “boat prisons,” say they want detainees removed far more rapidly from their ships, which they acknowledge were never designed to serve as detention centers. Drug Enforcement Administration agents say in court filings that rapid transfers to U.S. soil are logistically impossible, with few countries allowing airport transfers and a shortage of available D.E.A. flights. The Coast Guard says the agency patrols six million square miles, which creates “logistical and transportation challenges.”

But there’s evidence in those court filings that budgetary considerations may also add to the delays. In 2015, a Southern Command official suggested in an email to a D.E.A. agent who was handling a Coast Guard detainee transfer that the agency “may save costs to the taxpayers” when weighing the benefits of one route back versus another. In an April 2017 brief in a separate case, the government argued that pulling a cutter from normal drug-smuggling patrol to hasten a detainee transfer would be a “considerable waste of government resources and time.”

Coast Guard ships and frigates on loan from the Navy instead slowly fill up their hangars or decks, waiting to unload detainees when port calls can be arranged with foreign officials and flights arranged with the D.E.A. Other detainees are simply kept aboard cutters as they make trips back to San Diego or through the Panama Canal on the way to East Coast ports. No matter the route, federal judges have repeatedly waived normal protections against extended prearraignment detention, accepting the government’s claims that transferring detainees from the Pacific is too logistically complex to allow for a speedy appearance before a judge. And so over the years federal judges have allowed for progressively longer periods of detainment: five days in the Caribbean in 1985; then 11 in 2006; in 2012, 19 days in the Pacific. Average detention time is now 18 days. An official told me that men have been held up to 90 days.

Maritime- and human-rights-law scholars caution that the delayed periods of detention employed by the United States in its antidrug campaign run counter to international human rights norms. “In a European context, what the U.S. does would not meet the standard,” says Efthymios Papastavridis, a maritime-law scholar at Oxford University. “It would have to be measured against human rights and due-process law and this would be unlikely to pass the test.”

But Melanie Reid, a former federal prosecutor in the Department of Justice’s Dangerous Narcotics division, said the department’s position was that “the clock does not start ticking, in the procedural sense, until these people get to the United States and are arrested.” A senior Coast Guard lawyer wrote in a 2016 paper on maritime enforcement and human rights that “no remedy for these delays is generally available to defendants.”

On Nov. 21, 77 days after her husband left on his vuelta, Lorena Mendoza walked with her newborn in a stroller from Jaramijó to the nearby port city of Manta as part of a procession of the Virgen de Montserrat. Amid a crowd of thousands of people who had packed into the streets with brass bands, she prayed for her husband, imagining what her life would be like if he was really dead.

When she returned home, Mendoza saw that she had missed a series of phone calls from the United States. At 11 the next morning the phone rang again. “I am here,” Arcentales said. “I am alive.” Mendoza cried, overcome by a great swell of relief. “Thank God I can hear my family again, thank God you are all O.K.,” Arcentales said.

Several days before, the American ship had taken yet another trip to port, this time on the coast of Panama. This time the detainees were told to stand up. Guards unlocked their ankle cuffs and led them off the ship. He would see his family soon, Arcentales thought. Then he heard a guard announce: “Gentlemen, D.E.A. agents are waiting for you outside. You are going to the United States.”

Unlike domestic arrests, which stipulate that defendants be charged in the jurisdiction of their crime, maritime smugglers can be prosecuted anywhere, as long as it’s the first place they land or in the District of Columbia. American law-enforcement officials have developed a clear preference for prosecuting maritime smuggling cases in Florida, where federal agencies have set up interagency drug-task forces and prosecutors have expertise on maritime drug cases. Trying these cases in Florida may have made practical sense in the 1980s and even the 1990s, when the bulk of maritime interdictions took place in the Caribbean. But now that sea smuggling has shifted significantly to the Pacific, the desire to prosecute defendants in Florida’s federal courts has arguably played a role in the increasingly prolonged maritime detentions.

One reason few trials have moved to the West Coast may be that the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers California, has placed a significant limit on the reach of the U.S. Coast Guard. Unlike courts on the East Coast, the Ninth Circuit requires federal prosecutors to prove that drugs discovered on foreign-registered boats were actually bound for the United States. That decision, in 1994, returned the legal framework in California to something more like the one that existed nationally in the 1980s. Prosecuting smugglers found aboard a foreign-flagged ship without proving their cargo was intended for U.S. markets, the court found, violates Fifth Amendment due-process protections. “We try not to bring these cases to the Ninth Circuit,” said Aaron Casavant, a Coast Guard lawyer who until 2014 provided legal guidance to the service’s law-enforcement operations and recently wrote a law-review article defending the legal basis of extraterritorial drug enforcement. Casavant points to the fact that there are more lawyers and judges with maritime experience in Florida. But the Justice Department would likely lose a case like Arcentales’s in the Ninth Circuit, where there is a burden of proof. The majority of these cases are tried in the 11th Circuit in Florida, where no such burden exists.

An image placed in evidence in a separate smuggling case. On some Coast Guard ships detainees are held in hangers like this one, their ankles shackled to the ground.Image: COURT CASE RECORDS

Orlando do Campo, a private defense lawyer in Miami, has been assigned by the courts to handle 23 cases of maritime smuggling. “It’s like a nature documentary where you see the hawk grab the fish out of water, and the fish is there saying, ‘What the hell am I doing in the air?’ ” do Campo said. “For them that’s Florida. ‘A few weeks ago, I was in Ecuador, then I went into the middle of the Pacific and now I’m here?’ It’s entirely surreal.”

Arcentales, Quijije, Payan and the four Guatemalans were put on a flight to Florida. On Nov. 19, they were formally arrested. Arcentales says he told a federal agent all he knew about the operation. “But the truth is,” Arcentales told me, “I don’t know anything about it at all.” At least one other man in the group of seven talked to investigators, too, providing all the information he had: the route he’d taken and the last name of the enganchador who’d hired him. All seven accepted plea agreements. No motions were filed challenging the conditions of their extended detentions.

Such motions, in the rare instances when defense lawyers file them, have little effect. Lawyers for three men whose detention overlapped on a cutter with Arcentales petitioned a federal court to throw out their indictments for “outrageous government conduct.” The judge said he was troubled by detainees’ accounts of “inadequate nutrition, weight loss, lack of privacy for toilet use and lack of sufficient protection from the elements.” Even so, he said, the “inhumane treatment” had not been used “in an effort to secure an indictment,” so he could not dismiss this indictment. “This is not to say that such treatment of detainees is condoned by this court,” he added. “Far from it.”

On July 2, 2015, Arcentales and Castillo were taken to court for a sentencing hearing. In testimony before Congress this year, John Kelly attested that “suspects from these cases divulge information during prosecution and sentencing that is critical to indicting, extraditing and convicting drug-cartel leadership and dismantling their sophisticated networks.” But the judge presiding in the Arcentales case, Virginia Hernandez Covington, made it clear that the two men were of little use. “They are just trying to do it to make some money for their family,” Covington said in court. “The higher up you are, the more information you have. You’re more culpable. But you have more information.” She continued, “The lower level folks have less information to bargain with.” But defendants charged under the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act, even mules like Arcentales, are rarely provided reduced sentences on mandatory minimums, as a suspect caught on U.S. shores with the same quantities of drugs might be. Covington sentenced Arcentales to 10 years in federal prison and Castillo to just over 11.

When I met Arcentales for the first time at the Fort Dix federal prison in New Jersey in late 2016, his face had been transformed from the angular, gaunt one I’d seen in mug shots taken by jail officials shortly after his arrival in Florida. He appeared to have gained back the weight he’d lost at sea. We sat beside each other in the visitation room, set up like an airport waiting area, and talked in Spanish amid the drone of mothers and wives speaking in English to their incarcerated loved ones. Speaking slowly and precisely, he told me he had never considered before he was charged that by smuggling drugs he might be committing a crime against the United States. He wondered repeatedly why the United States would not let him serve his time in Ecuador. At least then he would have contact with his family, beyond a time-limited call every few weeks. He thinks about them constantly. And of the Coast Guard cutters he was detained on.

“I had a terrible nightmare about the chains,” Arcentales told me in the visitation room. “I would wake up feeling the chains digging into my ankle and jerk my leg thinking I was shackled, and feel my leg free and be relieved that I was not chained there on the boat. I would wake up sweating; almost crying, thinking I was still chained. Over time it passes. But a thing like this, it never leaves you.”

In the home that Arcentales had left behind, life is no less destitute than when he departed. Two weeks after Arcentales arrived in Florida, Mendoza opened a store in what was once their small sitting area, but it was a good day if it brought in $15. When I met her in Jaramijó, Mendoza welcomed me warmly into her home, which is crowded with her children and grandchildren and a flow of customers who step inside to buy diapers, plantains or cheese.

Both Mendoza and Arcentales assumed that his fate, now widely known in the community, would serve as a warning for those being approached by the enganchadores. In April at Fort Dix, Arcentales told me that if he could he “would tell everyone not to go, never take la vuelta!” But the vueltas have only increased since Arcentales went to prison. In April 2016, a catastrophic earthquake struck the Ecuadorean coast. Whole blocks in Jaramijó were leveled, leaving thousands homeless. Fishing boats and storage and canning operations were destroyed. Blue tents, supplied by the Chinese government as emergency shelters, remained a year later on the edge of the cliff that rises over the town’s now quiet docks.

- “If government’s argument is taken to its logical extreme, an individual could be detained indefinitely for a federal crime as long as the government did not file a formal complaint.”

The quake sent a flood of the unemployed, including impoverished fishermen, in search of smuggling jobs. In late 2016, Mendoza’s son-in-law Wladimir, who had been living in her house, disappeared. The young man had worked selling morocho, a homemade sweet corn drink, on the street ever since he hurt his back unloading fish in Manta. But that brought in only a few dollars a day, and he’d been telling his wife, Nelly, that he was thinking of taking la vuelta. Wladimir had never fished a day in his life, Nelly told me, and she never believed he would take the job. But in December 2016, Wladimir said he was going to the store and never came back. For six weeks, Nelly worried constantly about her husband, asking in Facebook messages if I could check to see if he was in a U.S. prison. In early February, one week before I arrived in Jaramijó, Wladimir called Nelly from a jail in Florida. A Coast Guard ship had detained him in the Pacific Ocean.

Wladimir’s court-appointed lawyer, Joaquin Mendez, argued in a federal court in Florida that the 31-day delay between his interdiction and his delivery to court in the United States was a violation of federal statutes requiring that defendants be arraigned within 30 days. “The Coast Guard made a calculated determination to continue on with their interdiction, to keep these individuals in the conditions that they were, while they’re going about doing their business,” Mendez told Judge James I. Cohn.

For what may have been the first time in federal court, Cohn dismissed the indictment against Wladimir because of the delay. “If government’s argument is taken to its logical extreme, an individual could be detained indefinitely for a federal crime as long as the government did not file a formal complaint,” Cohn said in court. But he threw the case out “without prejudice” — a small embarrassment for federal attorneys, yet one that allowed them to file a new complaint. In late August, Wladimir was sentenced to 10 years.

In Ecuador, government officials have publicly warned fishermen to refuse offers from enganchadores. Yet men are still making the trip, many traveling directly into the Coast Guard’s net. I met more than 20 families in Jaramijó and other towns who have lost men. A frail woman I met in her thatch home told me her oldest son, a fisherman, barely an adult himself, had provided the family its only source of income. Three months after the earthquake, the fish market stalls were still decimated, and only about a third of fishermen were working. He’d followed the flow of men out onto the high seas.

One evening in February, after the arrests of Arcentales and Wladmir, I sat with Mendoza under a pomegranate tree in the mud-rutted driveway outside Mendoza’s house. A group of her neighbors and relatives gather there most nights as the sun falls and the air cools. While we talked, a man carrying two gleaming swordfish walked by and waved. One of the men who lay in a hammock told me that the passing fisherman had recently taken la vuelta. Lorena pointed up the street to a new car parked against the curb. It had been purchased with vuelta money. As we talked, a young relative of Mendoza’s, who had until then lay quietly in a hammock, told me that he was thinking hard about taking a job, too. “I know it’s only about a 50 percent chance I’ll make it back,” he said. “I know what happened to Jhonny.”