At 6 a.m. on a winter morning in Ridgewood, N.Y., a woman I’ll call Valia leaned on her kitchen counter, drinking black tea and packing a giant purse. She wore her blond-gray hair in a bun and pulled on an ankle-length brown puffer coat. “OK, I’m taking my medication, I’m taking my telephone, my tablet,” she said, going down her checklist. She whispered goodbye to her cat and her 26-year-old son, who was still asleep, and lit a cigarette to smoke on her way out.

Valia took the L train to the end of the line in Brooklyn, then switched to a crowded bus. Her fellow commuters looked as tired as she did, some dozing upright in their scrubs or steel-toed boots or polo shirts embroidered with fast-food logos. I was following Valia, a Ukrainian immigrant, on her hourlong trip to the apartment of an elderly, low-income woman with advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Valia had been assigned the case, the latest in her long career as a home health aide, a few months earlier. The woman depended on her for virtually everything. “Showering, washing her hair, feeding her,” Valia said. “She’s bedridden, she’s not walking, so I have to transfer her from the bed to a chair. She’s using Pampers.”

Her shift would begin at 8 a.m. and end at 8 a.m. two days later — a schedule that had recently compelled Valia to sue her employer, a private home health agency. Forty-eight hours stuck in a cramped bedroom with someone in constant distress, who yelled or babbled strings of Russian words, who was incontinent and unable to sleep, who was lost in her own timeless world. “I can’t fall asleep knowing she will break a bone,” Valia said. “I sleep next to her and watch her all the time.” Over two days she would work more than most full-time employees do in a week. Yet her pay stub would account for only 26 of the 48 hours, at $10 per hour. (She now earns $13.) This was arguably legal, because the law — and her employer — assumed that she slept and ate the rest of the time.

“I’m never sleeping,” Valia said. “They didn’t even tell us they weren’t going to pay us nights. When I saw that on my paychecks, they said it’s a very specific kind of case and that at some time in the night I’m allowed to stop working and put my client to bed. But in reality, most of the clients I was assigned were never sleeping at night.” Still, Valia stuck with it, out of obligation to her clients and because she’d never known another career.

Privacy laws stopped me from following Valia into her client’s home, so we parted on an industrial block nearby. At the end of her 48-hour shift, I met her on the same corner. She wore the same outfit, hair pulled into the same bun. She was exhausted and irritable and complained of a sharp pain in her back from repeatedly lifting her client. “Come on!” she yelled. “Let’s go!” On the subway, she unfolded an hourly log she’d kept for my benefit, in lines of slanted Cyrillic punctuated by exclamation points: “Bed bath. Porridge + juice. Changing diaper. Intimate washing of patient. Transfer to the chair. Laundry. Gave her pills.” A one-hour nap on the first day was the most Valia had slept. She said this was fairly typical.

Medicaid, which was footing the bill, periodically sent a nurse to evaluate the patient and inspect the premises. On the last such visit, Valia said, the nurse had instructed her to turn the patient every two or three hours, to prevent bedsores. A patient with constant overnight needs is supposed to receive a “split shift” of two consecutive 12-hour workers per day. But because that arrangement doesn’t automatically deduct for sleep or long meal breaks, it would cost twice as much as Valia’s stay; the nurse knew it would never be approved and called on Valia to fill the gap. “She just told me verbally. It can’t be on my time sheet or in the care plan,” Valia recalled. “They pretend we sleep.”

Eighty million people in the U.S. will be 65 or older within a few decades, compared with around 50 million today, and, according to surveys conducted by AARP Inc., the desire to grow old at home is almost universal. Most who do so will need help with daily tasks and will exhaust the ability of family and friends to cook and clean, bathe and dress, and run errands. When Americans look for paid help, they’ll find their national infrastructure convoluted and wanting. It’s a problem the world over, but one compounded in the U.S. by the fragility of the welfare state.

A typical home-based care plan of six or eight hours a day is less costly, and more salutary, than a nursing-home stay, but it’s still expensive enough to bankrupt a middle-class American family. Medicare, the public benefit plan for those 65 and older, pays only for strictly medical forms of home care, such as dressing wounds and physical therapy, or for short post-hospital stints in nursing homes. Private long-term care insurance can be prohibitively expensive (annual premiums run into the thousands) and unavailable to those with preexisting conditions. Most seniors who need help with daily tasks first exhaust their savings, then apply for Medicaid, the public health insurance program for the poor.

Medicaid is jointly funded by the state and federal governments, but most rules are set in Washington. Certain services must be provided; states can then decide what else to cover and how much to spend. Nursing-home care is a mandated benefit, but nonmedical home care isn’t. The result is a chaotic national patchwork. A senior in Virginia is entitled to no more than 32 home visits per year; in Utah the cap is 60 hours per month.

In states with strict limits, many patients who would prefer to stay at home are placed instead in a nursing facility, at significant cost to the public — in 2015, about $55 billion. In states that do approve substantial home-based care, Medicaid budgets are underfunded to the point of crisis. As a result the nation’s 2.9 million home-care workers — who, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, earn a median annual income of $22,200 — are routinely pressed to donate their labor, pushing through required breaks, staying well beyond the hours set by their agency, or, like Valia, enduring long, uncompensated nights.

New York, one of the nation’s largest long-term-care markets and the only state whose Medicaid program covers around-the-clock help, comes closest to the future Americans say they want. But New York also demonstrates the system’s central problem: It’s untenable, given current funding levels, to pay workers for anywhere close to the number of hours they actually work.

“Tell me another job where you have to work for free throughout the night,” Valia said. “It doesn’t exist!”

The home-care industry is, like nursing, social work, and child care, an offshoot of traditional unpaid domestic labor. During the Depression, New York City introduced one of the U.S. government’s first experiments in monetized care, hiring black “housekeepers” with funds from the Works Progress Administration. As Eileen Boris and Jennifer Klein write in Caring for America, it was a paid gig, but one with faint boundaries; the women were expected to treat their jobs as charity. “If it seems necessary to work overtime, I tell my client we can check that up to neighborliness,” one WPA housekeeper said. Later, the Welfare Council of New York City drew on the same population of workers to provide relief to the poor, paying them for only 10 to 16 hours of every 24-hour shift.

With the establishment of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security in 1965, and their expansion in 1973, government at all levels took an interest in home care. The health-care system became one of the economy’s largest sectors, and states used home-based services to complement hospitals and long-term-care facilities. For the first time, elderly and disabled Americans lacking family help could participate in the community rather than being warehoused in institutions.

To staff these initiatives, in the 1970s and ’80s many cities and states developed “workfare” programs, conscripting poor women to give “unskilled” care (as opposed to nursing services) in exchange for a welfare check. Home health aides, unlike nannies and house cleaners, were viewed by policymakers as “companions” and casual “sitters” undeserving of the minimum wage. During congressional debates in 1973 over the exclusion of domestic workers from the Fair Labor Standards Act, Senator Quentin Burdick (D-N.D.) argued that home health aides should remain beyond the law’s reach. The prototypical aide, he said, was someone who just “comes in and sits”; aides were “not regular breadwinners or responsible for their families’ support.”

This assumption persisted and was further entrenched by federal welfare reforms passed in 1996, which vastly expanded workfare. Not until 2015, following Supreme Court litigation, a contentious rule-making process, and extensive labor organizing, did aides finally win the right to be paid the minimum wage and overtime. Even so, the median annual salary for full-time aides— overwhelmingly women, many of them immigrants and ethnic minorities — approximates the federal poverty level for a family of three.

- Most companies get around $3,000 per patient per month, enough to cover overhead and compensate an aide for a 40-hour week, but only one-quarter to one-half the cost of around-the-clock care.

Officially, Americans spend more than $300 billion per year on long-term care, including nursing homes, assisted-living facilities, and in-home care — six times the annual budget of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The total would be far higher if it accounted for gray-market domestic work or the country’s 21 million unpaid family caregivers.

Many households find help through a home-care agency. In 1980 there were 3,000 such companies; today there are more than 12,000, ranging from tiny neighborhood nonprofits to corporations employing thousands. Other households hire directly and pay out of pocket, increasingly relying on startups to do so. Earlier this year, the website Care.com, the Tinder of domestic work, reported that it had registered more than 14 million consumers and 11 million aides to upload detailed profiles, want ads, and résumés for senior care, child care, pet care, and housekeeping. When I posted my own bare-bones listing, seeking around-the-clock help for my fictional grandmother — at $15 to $25 per hour, well above the Medicaid rate — I received 50 responses overnight.

Medicaid remains the largest funder of home- and community-based services in the U.S., but sufficient public funds have never been allocated to make the system work. How much home care a patient receives through Medicaid theoretically corresponds to her medical need: Someone with early Parkinson’s disease might be granted two hours per day, whereas someone with severe diabetes and a bad hip might receive six. Doctors and nurses make these assessments, but insurance companies overseen by state Medicaid agencies must authorize them.

Once a case has been approved, Medicaid funds travel down a complex path. In New York, the state Department of Health pays a flat per-patient rate to a “managed-care” insurance company, which in turn contracts with home-care agencies, which in turn employ aides. The rate, once set for a particular insurer, doesn’t vary, regardless of how much help a patient needs, so the actuarial math for the most seriously ill — elders who are bed-bound or have advanced Alzheimer’s — is punishing. Most companies get around $3,000 per patient per month, enough to cover overhead and compensate an aide for a 40-hour week, but only one-quarter to one-half the cost of around-the-clock care. The total costs of a split shift can exceed $12,000 per month; a live-in shift, where nights go unpaid, averages $7,000.

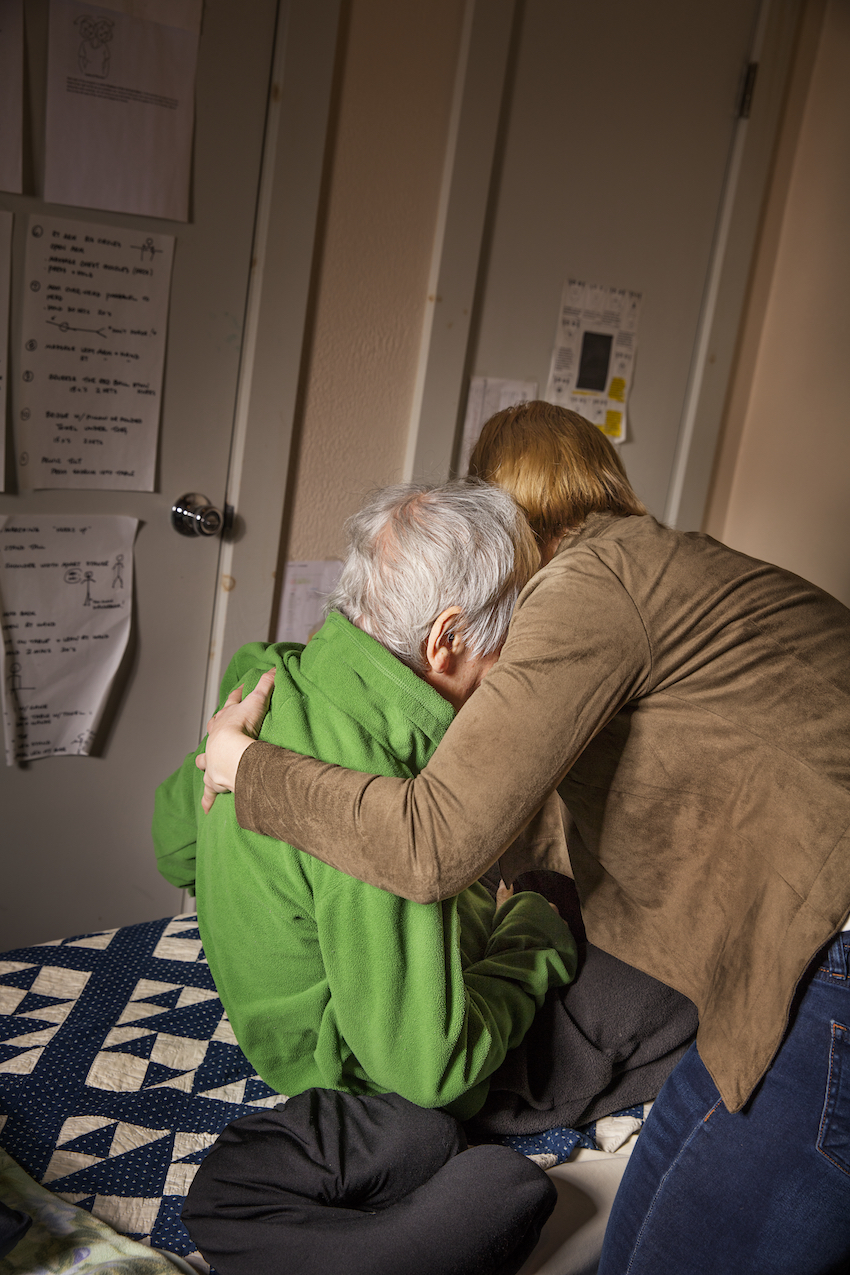

“She’s bedridden, she’s not walking, so I have to transfer her from the bed to a chair. She’s using Pampers,” says Valia.Image: Elinor Carucci/Bloomberg Businessweek

New York’s reimbursement scheme thus discourages managed-care companies and home-care agencies from accepting high-hours cases and masks the true level of demand. Only a fraction of the neediest Medicaid patients are granted 24-hour care, typically provided by a “live-in” worker like Valia, who’s paid for only half her time. And these high-cost cases have become concentrated among a handful of insurers with philanthropic roots.

The state Department of Health wouldn’t say what percentage of Medicaid patients receive 24-hour care. Local 1199 of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which represents more than 400,000 aides, nurses, and other medical workers on the East Coast, says live-in cases are 8 percent of New York’s total. But Rochelle Friedlich, of the Carter Burden Center for the Aging, says that’s because managed-care plans are “giving people fewer hours than we think might be safe.” Compared with only a decade ago, she adds, “it’s definitely much harder to get 24-hour care” — because of inadequate reimbursement rates and the growing population of seniors.

In 2016, GuildNet, a Medicaid insurer known for taking on high-hours cases, announced it would no longer pay for long-term-care services in three counties bordering New York City. “We can’t control the negotiation of rates or the numbers of people we have to cover,” Christina Wong, GuildNet’s chief financial officer, says. “You have an aging population getting older and sicker. How do you manage that?”

In less populous areas of the state and country, the problem is compounded by the lack of aides willing to work for low wages. A survey conducted last year in Wisconsin showed that 85 percent of home-care agencies didn’t have the workers to staff scheduled shifts. Di Findley, executive director for Iowa CareGivers, estimates that her state will need an additional 20,000 aides by 2020. “The demand is on the rise, and the supply is not enough,” she said at a recent community meeting. “It’s gotten so much worse in recent years.”

In February 2017, the New York State Assembly convened a hearing on the “aide shortage” crisis. “On any given week,” Rebecca Leahy, president of North Country Home Services Inc., testified, her agency has “400 hours of authorized care that cannot be provided due to a shortage of workers, leaving those unserved patients with a high risk of hospitalization or placement in a nursing home.” In some areas of the state, aides assigned to 8- and 12-hour jobs routinely stay 16 hours or more without additional pay. Colleen Johnson, a 58-year-old caregiver in Buffalo, said that agencies often ask her to cover additional hours and that she feels compelled to do so out of loyalty to her clients — out of neighborliness, you might say. “It’s all about the consumer,” she said. “If you do this work, you have to accept that.”

It was 20 years ago that Valia responded to an advertisement in one of New York City’s Russian-language newspapers. A local home health agency was offering training and the promise of steady work as a certified aide for elders and the disabled. Professional caregiving wasn’t what she’d imagined for herself — as a young woman in Ukraine, she’d studied French and planned a career in translation or journalism — but here she was, an immigrant, a mother of three, and the wife of an ailing man. Her husband got sick a few years after they immigrated to the U.S. “I didn’t have insurance, so we were fighting to get him covered,” she says. “I had to earn money to raise the children.” Valia tended to him as he lost his sight then slipped into a long coma. She stayed with him at the hospital and in a nursing home, where she witnessed the limitations of institutional care.

For many years there was little separation between Valia’s personal caregiving and what she did for a living. Until her husband died in 2011, she split her time between his bedside and her clients’, as if to prove the nebulousness of her profession. It was after his death that she worked her first 24-hour assignment — and later learned, to her shock, that only half the hours were paid. She called her union, SEIU Local 1199, to complain. A Russian-speaking organizer told her that nothing could be done: There was limited money in the Medicaid system. (The organizer declined to comment.)

In 2016, Valia heard that a group of home-care workers had filed lawsuits over unpaid time on 24-hour shifts. She was flat broke, living on 26 hours of pay each week but too tired from her 48-hour shift to take on anything more. She met with a lawyer in downtown Manhattan and decided to sue her longtime agency for unpaid overtime. More than a dozen class-action lawsuits have been filed in the state, with workers claiming that they weren’t receiving breaks and that their employers and union representatives ignored repeated complaints. The key questions in such cases are a mix of law and fact: Does the worker formally count as “live-in”? How much break time does she enjoy? Under state and federal rules, time spent eating or sleeping can be subtracted only if a caregiver actually takes mealtimes and sleeps for extended periods, and only if she “lives in” her client’s home.

- I asked a dozen 24-hour aides in New York state if they’d ever been advised of their right to sleep and eat on the job. All said no, and none had been told to keep track of naps and meals.

Ordinarily it’s the employer’s responsibility to track hours and compensation, but attorneys for the home-care industry have argued that this is impossible to do in private homes. An aide must rebut the presumption that sleep and meal breaks are being taken, they say, by complaining to a supervisor or making notes on her time sheet.

I asked a dozen 24-hour aides in New York state if they’d ever been advised of their right to sleep and eat on the job. All said no, and none had been told to keep track of naps and meals. The nation’s largest provider of home care, the Visiting Nurse Service of New York, includes only a brief, vague section on live-in shifts in its training manual. Aides are entitled to eight hours of sleep, it says, but they must also “be available to the client” as needed, for “a reasonable amount of time during the night.” When I asked Kathryn Haslanger, chief executive officer of the Jewish Association Serving the Aging, one of New York’s oldest home-care agencies, what type of around-the-clock patient needs close attention for only 13 of every 24 hours, she described a scenario in which “the client requires assistance at night for toileting, or due to impaired cognitive status,” but not all the time.

Valia hadn’t kept records over the years, though she could recall each of her clients and what she did for them in minute, bodily detail. One woman needed her diaper changed throughout the night; another wanted Valia to cover her with a blanket, then uncover her, for hours on end. Valia could testify about the hours she’d worked, but her union contract seemed to lock in pay deductions for sleep and meal breaks whether or not she took them. The contract also prevented her lawsuit from proceeding in the courts, instead forcing the case into arbitration. “I have to fight both 1199 and the agency for my rights,” she says.

Valia’s employer declined to comment, but in court filings maintains that she was compensated fairly, in line with state and federal regulations. The union’s position is harder to read. Over the past few decades the SEIU has unionized tens of thousands of aides, but to do so it struck compromises with home-care agencies and state governments, attempting to balance the need for fair jobs with the need for any jobs. The union’s contracts typically guarantee health benefits and protection from arbitrary firing, but they’ve done little to change the reality of unpaid hours. “Anytime workers can show, under the current rules, that they weren’t paid, we’re representing them,” says Helen Schaub, a policy and legislative director at SEIU Local 1199. “In an ideal world, we’d want to make sure workers get paid for all hours they’re in house. But a change to reimbursement would make home care very expensive.”

It’s difficult to know how many such hours go uncompensated nationwide — a representative from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services repeatedly declined to answer questions to that effect. The New York Department of Labor wouldn’t disclose information on wage complaints filed by home health aides, either. In a 2009 survey the National Employment Law Project found that 90 percent of home health aides had to work some hours off the clock, and workers in such diverse locations as Minnesota and Washington, D.C., have filed complaints over wage theft. I heard accounts of proliferating responsibilities and taffy-like schedules from those employed by Medicaid-funded agencies and private employers alike.

Valia’s own case effectively hit a dead end after being forced into arbitration, but thus far two appeals courts in New York have ruled that aides like her aren’t live-in workers and must therefore be paid for each hour they spend in a patient’s home. The decisions are prompting panic among home-care agencies and cheers from low-wage workers nationwide. The Home Care Association of America has warned that thousands of agencies are at risk of going out of business. Valia felt vindicated.

- In a hospital, there are rules - for the worker, for the patient. For us, we have nothing. The patient is the law.

On Oct. 6, only three weeks after the second appeals court ruled in favor of full compensation, the state Department of Labor quietly promulgated emergency regulations on sleep and meal breaks. But rather than clarify why around-the-clock workers are essentially “on call,” the revised language will likely make it harder for workers to be paid for more than 13 of every 24 hours. In the explanatory note attached to the regulations, the department stated that it wanted to “prevent the collapse of the home care industry, and avoid institutionalizing patients.” LaDonna Lusher, Valia’s attorney at Virginia & Ambinder LLC, says the document “reads just like the briefs we’ve seen from the industry.”

This local drama will continue to unfold on the national stage. Last summer, when the congressional GOP attempted to transform Medicaid from an entitlement into block grants that would leave far less money for home- and community-based services, activists staged sit-ins and noisy demonstrations. People in wheelchairs led the fight, just as they had in the early disability-rights era, four decades ago. Back then there was little camaraderie between people with disabilities and the home health aides who cared for them: Higher wages for the latter meant fewer hours of help for the former. This mistrust has softened over time. Still, any wage hike, any policy requiring aides to be paid for every hour, threatens to pit workers and consumers against one another once more.

As the first wave of 76 million baby boomers turns 70, our long-term-care infrastructure will bend from the strain. To keep up, the Medicaid budget will have to grow and properly reimburse managed-care plans. Home health aides will have to be recognized as medical professionals and paid accordingly. Nursing homes, a far costlier option, will occupy a smaller share of the market, and Medicare will have to chip in for long-term care. As Paul Osterman, a business professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, argues in Who Will Care For Us?, “by expanding the role of aides, not only do we improve their jobs and reduce the incidence of low-wage work in America, but we can also improve the delivery of care and save money while doing it.”

No country has gotten this quite right, but in aging societies around the world, the public sector has proved indispensable. In Japan, long-term-care insurance is subsidized by the state, and in France, an expansive home-care network is covered by a mix of federal and local budgets. Yet the world over, family caregivers and private aides fill untold additional hours.

Valia sees her lawsuit as an attempt to bring order to this labor and to the home-health-care industry at large. “In a hospital, there are rules — for the worker, for the patient,” she explains. “For us, we have nothing. The patient is the law.” Yet she speaks empathetically of her clients’ predicament and the value of getting care at home: “My husband was in a nursing home. They sit you on a couch, and you stay like that all day. You have to live with everyone else. But at home, you’re in control. If you want to sleep, you can sleep. If you want to eat fish, you can eat fish. It’s better, of course. I’d prefer to stay home. Everyone would.”

I usually visited Valia on Wednesday nights, after she caught up on sleep, to chat about work and get the latest industry gossip. She’d respond impatiently to my questions while her cat prowled the linoleum. “I’ve lived here for 12 years,” she often said, gesturing to her apartment as a Russian variety show blared from the TV. “I’m waiting for Social Security. I’m 62 — I’m going to take my pension, and that’s it.” Her fridge was adorned with photos of her kids and grandkids, spanning New York, New Jersey, and France. Inside, the shelves were almost empty.

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations.

Correction: A previous version stated that, in 2016, GuildNet announced that it would no longer pay for long-term-care services in greater New York City. This was corrected to reflect that GuildNet’s announcement was in reference to three counties bordering New York City.