The call came just before noon on August 26, minutes after we had crossed a hilly range that separates northern Uganda from South Sudan. Earlier that morning, I had embarked on a four-day embed with South Sudan’s main opposition movement, the SPLM-IO, traveling on foot through rebel-held parts of the country to shed light on the latest surge of violence in the four-year civil war.

We had just passed a pile of rocks atop of a hill that marked the border when my phone rang, hanging onto the last sliver of cell phone coverage. Through the crackling line, I could hear the high-pitched, distressed voice of a rebel official, whom I had met just days before in the Ugandan capital of Kampala. An American journalist had been shot in South Sudan, he yelled through the phone. At first, with lack of details on the incident or the journalist’s identity, I thought the dreadful news would turn out to be a rumor. It wasn’t until the next morning that the rebel commander I was with confirmed the death of freelance journalist Christopher Allen, a dual British-American citizen and the first foreign journalist to lose his life reporting on South Sudan’s conflict.

Allen was killed in the early hours of August 26, while covering a rebel offensive in the town of Kaya, located near South Sudan’s border with Uganda. The aftermath of his death was marred by confusion and controversy, the full extent of which I only began to grasp days later, when I returned to cell coverage in northern Uganda and found my phone inundated with messages about the incident. The sequence of events that led to Allen’s final moments remained blurry and subject to conflicting statements. The South Sudanese government, believed responsible for firing the fatal shot, labeled him a “white rebel” and threatened other journalists who traveled to rebel areas with similar consequences. The rebels, in turn, deployed a carefully crafted narrative aimed at diverting attention from their own failures to protect the journalist.

Questions of what went wrong, and whether Allen’s death could have been prevented, echoed among the small community of journalists who reported on South Sudan. When a journalist dies, such questions, while on everyone’s mind, are often asked in a whisper amid fears of upsetting grieving relatives or tarnishing the legacy of the deceased. But not searching for answers, I felt, would be to fall short of my journalistic duties to establish what, exactly, had happened. It would also mean foregoing an opportunity to draw important, albeit painful, lessons for other journalists and editors covering South Sudan’s war.

Throughout South Sudan’s most recent conflict, the government has treated journalists with scorn. Since fighting broke out again in 2013, South Sudan has steadily slid down the World Press Freedom rankings published by Reporters without Borders (RSF). In 2012, South Sudan ranked 124, but by 2017 it had dropped to 145. Local Journalists risked harassment, arbitrary arrest, and even death for criticizing the government. In 2014, the country’s Minister of Information warned journalists against reporting from opposition areas, threatening that they could face arrest for “disseminating poison.” It was as if the rebels-turned-ruling party had forgotten that not too long ago, the foreign press had covered their own insurgency against Khartoum, contributing in minor part to galvanizing international support for the independence struggle.

- When a journalist dies, such questions, while on everyone’s mind, are often asked in a whisper.

Things took a turn for the worse in the latter half of 2016, especially for foreign correspondents, who had thus far largely evaded censorship and harassment. In July 2016, fresh fighting erupted in the capital of Juba, marking the collapse of a US-backed 2016 peace agreement. As the war unfurled across the previously peaceful region of Equatoria, the government banned 20 foreign journalists (including this story’s author) from entering the country, accusing them of writing “unsubstantiated and unrealistic” stories that “insulted or degraded South Sudan and its people.” Press freedom groups and journalist associations denounced the crackdown. “This ban on foreign journalists is aimed at creating a blackout on what is happening within the country,” said Clea Kahn-Sriber, the head of RSF’s Africa desk. Journalists who were still able to secure visas had to accept mounting restrictions of movement. The result was that very little information on the events in Equatoria reached the outside world, even as the UN warned that ethnic killings could spiral into genocide.

Against this backdrop, Christopher Allen reached out to South Sudan’s rebels in the summer of 2017 to arrange an embed. “My goal is to spend time with the opposition forces in the field to try to understand them,” the then 26-year-old (Allen would have turned 27 this past December) wrote to the SPLM-IO’s deputy military spokesperson, Lam Paul Gabriel. Allen was a freelance journalist who had dedicated himself to covering what he felt were invisible wars. Filing mostly for Al Jazeera English and The Independent, he reported from the trenches in Ukraine and interviewed Kurdish guerilla fighters in Turkey. South Sudan would be his first war on the African continent.

Allen arrived in Kampala on August 1. Three days later, he and Gabriel boarded a night bus bound for the northern Ugandan town of Yumbe, just 20 miles from the border with South Sudan. On August 5, Allen entered Kajo Keji county. He was only the seventh journalist to set foot in rebel-held Equatoria since the re-escalation of fighting in July 2016. In February 2017, independent reporter Nick Turse briefly snuck across the border near Kajo Keji to verify allegations of a gruesome killing at the hands of government forces. In April, an Al Jazeera TV crew paid a day’s visit to rebel forces near Kajo Keji. A couple of weeks later, reporter Jason Patinkin and I spent four days inside rebel-held Kajo Keji, filing reports for IRIN, Foreign Policy, France24, and Vice News.

But Allen’s trip to rebel-held South Sudan would be unprecedented in its duration. A freelance journalist who had the time and appetite for delving into his stories, he intended to stay with the rebels for several weeks. “His only motivation was to find out exactly the truth about the war in South Sudan,” Matata Frank, the rebel governor of Yei River state, told me during a meeting in Kampala this past December. Frank was one of the most senior SPLM-IO commanders in the Equatoria region and the first of a dozen people I would interview in order to piece together Allen’s final days.

For two weeks, Allen stayed with Frank at his headquarters in Panyume, sleeping in neighboring mud huts and sharing meals of posho (a doughy ball made of maize flour and water) and beans in the evening. The rebels, yearning for international news coverage and unaccustomed to hosting a journalist for such a long period of time, quickly grew to appreciate him. “We had really a lot of hope in him,” Frank told me. “Everybody was banking on him when he gets back [to tell] their real, actual stories that people are going through.” During his time in Panyume, Allen took extended walks to surrounding villages, accompanied by a couple of guards and his minder and translator, to speak to civilians about the impact of the war and their life under rebel rule.

But the young journalist wanted more. “From the very first day, he wanted to cover the actual fighting,” Frank told CJR. “He kept on asking me especially, when are we going to the war? Where are we going to attack?”

Frontline reporting from South Sudan has been scarce. A country with one of the lowest population densities on the continent, South Sudan has too few fighters and too much land for frontlines to exist. Unlike in Iraq, for example, where journalists board Humvees with American-trained special forces to be ferried within yards of combat, South Sudan’s war is remote and unpredictable. Clashes take place mostly in underdeveloped rural areas that are difficult and dangerous to reach, with few options for extraction in case of an emergency. Fighting is highly asymmetric, a factor that further complicates frontline coverage. The government, equipped with tanks, 12.7mm machine guns, and practically unlimited ammunition, controls the towns and main roads. The rebels, armed with AK-47s and the odd PK machine gun or Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG), lay ambushes along main roads and occasionally raid army barracks. Even when the rebels attack and overrun towns, they hardly ever hold ground.

These ground truths make embedding with the rebels a precarious undertaking. Not only are they outgunned—they also consistently overestimate their own military prowess. When I traveled to Kajo Keji in April 2017, the rebels took us within three kilometers of the frontlines, to a place called Loopo. On the way to the embattled hamlet, Brigadier General Moses Lokujo boasted that his men had surrounded government forces in Kajo Keji town to the extent that they couldn’t even fetch water from a nearby borehole. But as we bounced along the dirt track, Lokujo also pointed out a spot where the government had attacked rebel positions just two weeks earlier, clear proof that they were able to venture well beyond said borehole. On the same trip, Lokujo promised he would capture Kajo Keji town within three months, a goal that never came to fruition.

The rebels’ inferior yet overstated military capabilities, coupled with Allen’s limited knowledge of South Sudan to critically examine their propositions, proved to be catastrophic during the battle of Kaya.

Kaya is a small, sleepy border town nestled between undulating, green hills and the Kaya river, which marks the boundary between South Sudan and Uganda. The dusty main drag curves around the hills and cuts through the center of town, abutted by one-story concrete buildings that house shops and restaurants. Thatched mud huts extend from the main road onto the flanks of the hills.

Facing Kaya, just a hundred meters from the river where the dirt track ends and the paved road begins, lies the Ugandan border town of Oraba. Trucks bearing fuel and other commodities destined for South Sudan park near the customs checkpoint to clear paperwork. Ugandan forces, the most important ally of South Sudan’s government since the onset of the war, are deployed on the other side of the border.

Throughout the conflict, Kaya has remained firmly in government hands. Though it dwarfs the main border crossing of Nimule in traffic and customs revenues, Kaya remains an important entry point for goods and a source of government income. The town also bears military significance. The government sometimes channels reinforcements through Kaya brought from other parts of South Sudan via Uganda, a route that avoids travel through rebel held areas where they risk being ambushed.

The border town of Kaya as seen from the Ugandan side.Image: Simona Foltyn

It was the strategic nature of Kaya that prompted the rebels to plan an assault on the town and other government positions along the 16-mile road toward Morobo. The objective of the operation was to capture ammunition, cut off supply routes for the government, and, according to the rebels, preempt an impending attack. “The government was building troops there, and the intention was to increase the capacity of the fighting force in Kaya so they come after us in Panyume,” said rebel governor Matata Frank. For Allen, the waiting had finally paid off. He would cover one of the most significant military operations in the region that year.

Major General John Mabieh, a Nuer who hails from the same tribe as the SPLM-IO chairman Riek Machar, was to lead the battle. Around 250 rebel troops, half ethnic Nuer and half Equatorians, would attack Kaya and nearby government outposts at Bindu, Kimba, and Bazi. The rebels would assault the barracks, raid their ammunition stores, and chase their enemy toward Uganda. “Our intent was [to] capture Kaya. We wanted to have that border so [it] cannot be used again,” the SPLM-IO’s chief of intelligence for the area, whose name cannot be disclosed for security reasons, told CJR.

While the rebels procured medical supplies and mobilized troops from nearby areas, Allen joined a team of rebels conducting reconnaissance missions aimed at collecting intelligence for the forthcoming battle.

But the rebels’ ability to plan, let alone execute, such an operation fell short of their ambitious goals. Information of an impending attack had leaked weeks before. Rebel intelligence officials had imprecise information about the number of government troops based in Kaya, Bindu, Kimba, and Bazi, with estimates ranging from two to 800 troops. The very idea of capturing Kaya was unrealistic, according to one former SPLM-IO intelligence officer who had been part of previous assaults on Kaya. None of the operations had been successful. “We cannot take the town,” said Col. Emmanuel Augustino, who defected to a rival rebel group in 2017. “If you want to control Kaya, you need many ammunitions and machine guns.”

In what would turn out to be the most serious of miscalculations for their mission, the rebels had banked on raiding ammunition stores to top off their limited supplies during the battle. But the government, wary of a potential assault, had distributed all supplies to soldiers. Rebel commanders were made aware of this at least a day before the attack, according to one officer who took part in the battle. “I was thinking that going to Kaya, we will never succeed because of limited ammunition,” said the officer, who asked not to be named because he spoke outside of the chain of command.

- The commanders, wary of upsetting their visitors and eager for media exposure, let the journalists have their way.

The rebel commanders knew their mission could fail. During a pre-battle briefing in Yondu on August 25, the chief of intelligence said he advised senior commanders to not let Allen and two other Reuters journalists who had arrived that day join the troops. “Journalists shouldn’t go direct to the frontline. Maybe [the forces] could not take the town,” he told CJR. The intelligence officer said he tried in vain to convince the three reporters to remain behind with Mabieh and spokesperson Gabriel until the town was cleared. “They refused, all of them,” he said. “I was like, what can I do?” The commanders, wary of upsetting their visitors and eager for media exposure, let the journalists have their way. Reuters declined to allow their two journalists to speak about their time with Allen for this article.

In the evening hours of August 25, the troops and the three journalists left Yondu and advanced southwest toward Kaya, trailing northwest of the Uganda South Sudan border. They walked through the night along bush paths surrounded by tall elephant grass, until they reached Kaya in the early morning hours. Then, they waited for the break of dawn.

At twilight on August 26, the rebels, equipped with, on average, two magazines each, launched a multipronged attack on Kaya and surrounding government positions. The three reporters, none of whom wore body armor, according to rebel sources, moved with a large group of more than 100 soldiers, who looped toward Congo and descended onto the town from the northwest. The journalists were assigned a group of fighters to protect them, and were instructed to remain behind as the front moved ahead.

Dressed in a colorful array of military fatigues and civilian clothing, the rebels each wore a bright red piece of cloth around their heads to identify fellow fighters. Their ragtag appearance mirrored their clumsy combat etiquette. A Reuters video of the battle shows fighters haphazardly lurching toward buildings that appear to be on the town’s edge. There was no apparent formation. Some soldiers casually dangled their AK-47s by their sides, even as bullets whizzed past. Others emptied their precious magazines in a matter of minutes, surprising conduct for a force that prides itself in efficient marksmanship.

Many soldiers seemed disoriented. Originally from the northern Upper Nile region, the Nuer fighters were alien to this land, almost certainly entering Kaya for the first time in their lives. “We have to be careful! We don’t know where they are hiding,” one soldier calls out in the video. The chaotic nature of the assault raised concerns even within the ranks of the SPLM-IO. A rebel officer from the Equatorian region who took part in the attack expressed dismay at the reckless behavior of the Nuer forces. “After the first person starts [shooting], immediately everyone is running to the enemy,” he told me.

Chaos continued to unfurl as the battle went on. Allen was embedded with a group that was supposed to target the barracks, perched halfway atop a hill to the northwest, to secure ammunition. The soldiers found none, but continued their assault, even though they risked running out of bullets. The government troops deserted the barracks and fled south toward Uganda, with rebels in hot pursuit. But urban warfare wasn’t the guerillas’ strong suit. Passing mud huts and concrete structures, they neglected to clear the buildings along the way, making themselves vulnerable to attacks from government soldiers who had taken up positions inside the houses.

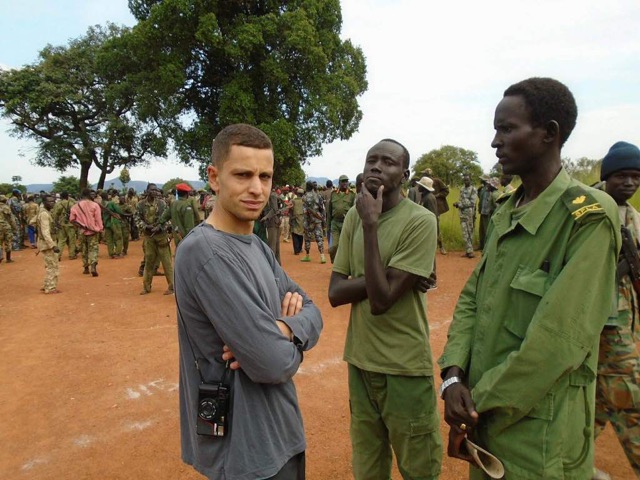

Christopher Allen with fighters from the SPLM-IO in Yondu, a few days before the battle of Kaya.Image: Courtesy SPLM-IO

In the course of the battle, Allen separated from the other two journalists and advanced with a group of soldiers headed south, in direction of the Ugandan border. The last sequence of photos found on his camera shows the advancing front: He was running a few yards ahead, capturing images of rebel fighters facing the camera as they charged onward. “Chris is very fast. Even me, I was getting tired running after him,” his minder said of the event.

Much of what happened next remains a blur amid conflicting accounts of Allen’s killing, provided by two fighters who were in close proximity when he died and four others with firsthand knowledge of the incident. There are contradictory statements, for example, about the precise type of gun that fired the shots. It’s also difficult to establish whether Allen was targeted, and whether he was the only person killed in his group. What is certain, however, is that the journalist was shot several times at close range. According to two witnesses, a soldier from the SPLA fired a large-caliber machine gun at Allen’s group from one of the concrete buildings on the main road, just 30 to 50 meters away. What is believed to be the fatal shot hit him in the head from the left. A total of five gunshot wounds were later found in his body. The timestamp of the last photo believed to be taken by Allen reads 6:52am, suggesting he may have died around that time.

The rebels reportedly attempted to extract Allen’s body, but failed amid sustained gunfire. Upon orders from the chief of intelligence, they grabbed his camera, backpack, and jacket, and emptied his pockets. Soon after Allen was shot, and only 40 minutes after the battle had begun, the rebels ran out of ammunition and retreated toward Yondu. In the afternoon, a government helicopter brought Allen’s body to the capital of Juba, where his identity was confirmed. News of the journalist’s death spread like wildfire through social media, fanned by inflammatory remarks from government officials who labeled him a “white rebel.”

The rebels were quick to give their own version of events. “SPLA IO Captured Kaya, Bindu, Kimba and Bazi,” reads a press release posted on Facebook on August 27 by spokesperson Gabriel. “The enemy forces are confined at the Uganda border.” The statement was published long after the rebels had been forced to withdraw. Beneath such efforts to save face, the SPLM-IO reeled from their embarrassing defeat. “Fighting without proper tactics and considering size of enemies with their equipments, it’s a disaster,” said one member of the SPLM-IO in an internal WhatsApp group, according to a transcript obtained by CJR. Some worried their incorrect accounts of the battle would reflect poorly should the US investigate Allen’s death. “We need to stop looking foolish by spreading false propagandas when we are the one being defeated,” said another rebel official.

It was the first time a foreign journalist had been killed in South Sudan. But it was the government’s reaction to Allen’s death that turned the event into a dangerous precedent, causing international outrage and instilling fear among those who reported on the country. In calling him a “white rebel,” the government denied Allen the status of a civilian he deserved under international law, thus absolving its soldiers of responsibility. And officials further threatened other journalists who embed with rebels. “Anybody who comes attacking us with hostile forces will meet his fate,” a government army spokesperson told reporters not long after Allen’s death. Though the government has since toned down its rhetoric, calling Allen’s death “unfortunate,” it has no plans to conduct an investigation into the incident. “There is nobody that can be accounted because he is at the frontline with rebels and he entered South Sudan illegally,” Deputy SPLA Spokesperson Santo Domic recently told CJR.

In the absence of an independent investigation, one important question remains unanswered: Was Allen targeted for being a journalist?

The information available at the time of publication is inconclusive. Contrary to initial reports, Allen wasn’t wearing a flak jacket or any other apparel that identified him as press, according to several rebel sources. A picture of his body shared on social media shows the same red band worn by the rebels tied around his left arm, which means government soldiers could have confused him for a fighter. (One rebels claimed the government later planted the band to fuel allegations that Allen was a mercenary, but other evidence, including this video of journalists wearing such bands during past embeds, casts serious doubt on those claims.) According to one Ugandan intelligence official who spoke to government soldiers shortly after the incident, the SPLA genuinely believed they had killed a mercenary fighting alongside the rebels. While such claims could be a conscious attempt to sidestep responsibility, they could also reflect a genuine, if unfounded, belief about foreign fighters that the government has previously tried to cultivate.

Other details, however, suggest Allen may have been intentionally killed. It’s difficult to imagine that a soldier shooting from 30 to 50 meters away couldn’t have properly identified Allen, who carried two cameras and was snipping pictures until what may have been his last moment. Having separated from the other two journalists, he was also the only white man in his group, and presumably the only one not carrying a weapon. The fact that Allen was shot several times could point toward an intentional killing, especially given that the rebels suffered few casualties (seven fatalities, according to the rebels; 15, according to the government).

Finally, there’s the uncomfortable question of whether Allen’s death could have been prevented. It’s unlikely that a helmet and bulletproof vest could have saved his life, in light of the multiple, large-caliber rounds that entered his body. For journalists covering war zones, the decision of whether to wear body armor always comes as a trade off between mobility and protection. In this instance, the tedious, long walk from Yondu to Kaya made carrying a 20-pound flak jacket impractical, especially given that the rebels don’t wear body armor and are already difficult enough to keep up with.

- There may have also been an element of competition that drove him forward. After all, reporting is often about who gets the story first, and who gets it best.

But should the journalists have covered the battle at all? Allen appeared to be driven by a genuine desire to shed light on an undercovered conflict. He told rebels that he wanted to report the war itself, not just the immense suffering left in its wake. “Very little has been done to try to actually articulate who [the rebels] are, what they are fighting for,” Allen told Gabriel in June while planning the trip. It was his newness to South Sudan that made it challenging to weigh the risk of such endeavors.

There may have also been an element of competition that drove him forward. After all, reporting is often about who gets the story first, and who gets it best. When the Reuters journalists unexpectedly showed up, rebels say Allen first reacted with disappointment. A freelance journalist who had yet to place his stories, he knew he’d struggle to compete against the wires. “Allen, he didn’t want rivals around, so he was not very happy when he saw [them],” said Gabriel. “Their presence gave him that pressure, that he wanted to cover something more.”

Such sentiments, if true, wouldn’t be uncommon in a cutthroat industry in which journalists compete for an ever-declining pool of finances. I felt the same desire to protect my turf when Allen first reached out, asking for rebel contacts three months before his trip. I provided the contacts, but I didn’t volunteer any other information on how to navigate rebel-held South Sudan, a mistake that has been a great source of guilt. The same desire for exclusive coverage may have also stopped him from divulging details of his plans when he wrote again at the end of June to let me know he’d be traveling to South Sudan soon. In the end, we were both freelancers pitching stories to the same few outlets that still cover international conflict, and a war that commanded little attention amid reports on Iraq, Syria, and the Trump administration.

At the same time, the bar for what the industry considers noteworthy coverage of conflict continues to rise, pushing young freelance journalists looking for a break beyond what many experienced media professionals deem safe. “There’s obviously some pressure to take what I would consider unacceptable risk to get ahead,” said Tim Freccia, a veteran filmmaker with more than 30 years of experience covering conflicts. To reporters working in South Sudan, Freccia is particularly well-known for a groundbreaking documentary shot during the first and most violent months of the war, portraying an audacious journey deep into rebel territory to meet rebel leader Riek Machar. The film, Freccia admits, may have sent the wrong message to young journalists. “On the surface, you know, it may have seemed like we just rocked up in South Sudan and hooked up with Riek Machar,” Freccia told CJR. “But it was a lot more complicated than that. It was something we set up over months through a lot of intimate, trusted contacts.”

Allen reached out to Freccia a week before he entered South Sudan. “First, let me say that I respect your work and particularly appreciated your South Sudan stuff,” the young journalist wrote. “I’m headed down to South Sudan on Monday to spend a couple months with the rebels. I was wondering if you had any thoughts or advice.” Freccia replied with words of caution. “I’d be especially wary of the Juba regime. They operate with complete impunity,” he wrote. Freccia offered to speak on the phone, but the conversation never took place. Allen sent a final message just before he entered South Sudan. “I leave for the rebels in a few hours anyway so I guess we will just have to see how it goes.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations.