For victims of sexual harassment on Wall Street, the case of Kathleen Mary O’Brien was a bad omen.

In 1988, O’Brien, then a stockbroker at Dean Witter Reynolds, filed the earliest sexual harassment case we could find in a public database maintained by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Wall Street’s self-governing organization, which is overseen by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The year before, O’Brien had sued Dean Witter in Los Angeles Superior Court, but the brokerage firm successfully argued that she was legally bound to use Wall Street’s closed-door arbitration forum, then run by a FINRA predecessor, the National Association of Securities Dealers. The arbitrators’ decision in her case would turn out to be a common one in harassment cases over the following years: The claim was dismissed. The panel, offering no explanation as to how it came to the decision, charged her $3,000 in arbitration fees.

O’Brien’s case is one of 98 sexual harassment or hostile work environment claims and counterclaims made by women that The Intercept and the Investigative Fund found in the FINRA database over the past 30 years. FINRA does not categorize the cases in its database, so to assemble our list, we searched for words and phrases including “sexual harassment,” “hostile environment,” “sex,” “sexual,” and “harass.” Our analysis is based on FINRA arbitration awards, brokers’ regulatory records from FINRA and state securities regulators, and court records. FINRA’s database includes legacy cases from the authority’s two predecessor organizations — the NASD and the New York Stock Exchange — which we refer to here as FINRA cases. On March 14, in response to a request for information about sexual harassment on Wall Street, FINRA turned over a summary of arbitrations from the years 2010 to 2018 to Sen. Elizabeth Warren and two other Democratic senators.

Employment lawyers say the number of harassment cases we identified in the database is eclipsed by the countless disputes in which women quietly settled before a claim was ever filed, motivated by offers from employers anxious to keep grievances from appearing on a public website. Nor does the database include the many cases that were settled before arbitrators had a chance to rule — roughly 60 percent of all FINRA cases in recent years. It also doesn’t include the cases that get resolved by other forums, such as the American Arbitration Association.

And then there are the many women who decide not to take the risk of complaining in the first place. “We need our jobs,” said Stephanie Minister, a veteran Wall Streeter and president of the Boston Securities Traders Association. “There’s only so much bitching and moaning we can do.”

Among the 97 cases that reached a decision (one claim was withdrawn), only 17 women explicitly received an award for harassment or hostile work environment. Three and a half times that number wound up being dismissed or denied — 60 cases in all. Eighteen women received awards in which arbitrators either denied their gender claims and gave awards on unrelated claims, or failed to make clear which among a diverse set of claims was being remedied by the award. And two were resolved with arbitrators simply recommending that derogatory information be expunged from the women’s records — information the women’s bosses put on their records only after they complained of harassment.

A handful of sexual harassment cases were also brought by men. Among the 14 cases we identified, four men won their arbitrations, one received an award on an unrelated claim, eight lost, and one resulted in an expungement. Overall, the men fared better than the women, winning their harassment claims 29 percent of the time, compared to 18 percent for women.

Our findings provide a window into the dysfunction that can result when a private justice system attempts to address sexual harassment in the workplace. Like other arbitration forums, FINRA is a black box. It does not make complaints, transcripts, or other legal documents available to the public or the press, which protects harassers from exposure.

- “The chances of prevailing with an employment case are slim” for lawyers unfamiliar with FINRA arbitration. “So lawyers just don’t want to take the cases.”

The authority oversees and licenses brokers, branch managers, partners, officers, and directors at over 3,700 member firms, levying fines and suspending or barring brokers, firms, and executives through its enforcement division. Its enforcement arm fined members $73 million last year and ordered them to pay another $66 million in restitution.

FINRA currently oversees 630,000 brokers, the equivalent of the population of Las Vegas, yet it has only adjudicated, on average, three incidents of sexual harassment a year. It is striking that of the more than 55,000 claims decided by FINRA arbitrators over the past 30 years, only 97 dealt with sexual harassment. FINRA spokesperson Michelle Ong said that, on average, the authority gets fewer than 10 sexual harassment cases a year.

The numbers raise an uncomfortable question: Given that so many women on Wall Street are contractually required to resolve their disputes through arbitration, why do so few bring their sexual harassment claims to FINRA?

FINRA has its roots in a 1938 amendment to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the law that created the SEC. The act called for the formation of a national securities association that would supervise the conduct of its members, under the SEC’s oversight. For years, the NASD and the New York Stock Exchange each played that role separately; their 2007 merger created FINRA.

Although FINRA, a not-for-profit, derives its authority from the SEC, it is not a governmental agency subject to open meetings laws or Freedom of Information Act requests. It does, however, write rules that are subject to SEC approval, and the targets of its administrative enforcement actions can appeal to the SEC for review.

FINRA also operates the nation’s largest arbitration forum for securities industry disputes, where arbitrators have the authority to order industry wrongdoers to compensate customers for losses — and adjudicate industry disputes, ruling on a range of cases related to everything from the poaching of star brokers to misconduct on the job. Arbitrators also have the authority to recommend that negative information be scrubbed from brokers’ records.

Women face a tough fight when they bring cases against their Wall Street bosses. Many employment lawyers aren’t familiar with FINRA’s procedures, said John Garner, a Willows, California, lawyer who lost an employment case on behalf of a male client before FINRA last year, and wins are hard to come by. “The chances of prevailing with an employment case are slim” for lawyers unfamiliar with FINRA arbitration, he said. “So lawyers just don’t want to take the cases.”

In our research, the women who won their harassment cases before FINRA came away with as little as $6,825; in three decades, only two got awards of $1 million or more. The single largest award was for $3.5 million. (In the rare cases in which women are not bound by mandatory arbitration and are free to go to trial with harassment cases, the judgments can be far larger. Carla Ingraham, for example, a former sales assistant at UBS, won a $10.6 million jury verdict on her discrimination and harassment lawsuit, though she later settled for less, rather than fight UBS in appeals.)

- A branch sales manager alleged that one of them raped her in the office and threatened to kill her if she told anyone.

And winning in FINRA doesn’t necessarily mean a woman collects all that she’s owed. In 2004, FINRA arbitrators considered a complaint against Southwest Securities, a Dallas firm, and three of its male brokers who worked at a Long Island branch. The branch sales manager, Kim Marie Vescova, alleged that one of them raped her in the office and threatened to kill her if she told anyone, according to the panel’s summary of her testimony. She also testified that the men at various times had bitten her on the buttocks, grabbed her breasts and asked for milk, and pulled down her pants.

The arbitrators said her testimony did not prove rape, though they told the firm to pay her $300,000 in compensatory and punitive damages, plus nearly $30,000 in back pay, and ordered one of the men, Michael Aspler, then the branch manager, to pay her $100,000 for physical assault, verbal abuse, negligent supervision, and infliction of emotional distress. Contacted recently, Vescova said that after the firm had threatened to tie her up in appeals court, she settled for “pennies on the dollar” on those FINRA awards. (Hilltop Securities, parent of Southwest, did not respond to a query; Aspler declined to comment.) The arbitrators also ordered the two other men, Robert Mitchell and Mark Kern — the broker Vescova accused of rape — to pay her $25,000 each for verbal abuse, assault, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. But neither paid her. FINRA suspended both of their licenses five years later — not because of what they’d done to Vescova, but for failing to pay the judgment. Mitchell and Kern did not respond to queries sent to their last known emails and addresses. FINRA asks brokers to report only investment-related customer disputes to be included on their records, so the findings against the men were not detailed in their BrokerCheck records.

Ong, the FINRA spokesperson, said that a review of arbitrator decisions since 2010 shows no unpaid awards for workplace harassment. Vescova’s award was from 2004.

People leave Merrill Lynch's offices in the World Finanicial Center September 15, 2008 in New York.Image: Chris Hondros/Getty Images

Wall Street had its #MeToo reckoning in the 1990s, less than a decade after O’Brien filed her case, as thousands of women challenged their bosses in headline-grabbing gender discrimination and sexual harassment lawsuits. Many of those women had better luck than O’Brien, who was not reachable for comment. Beginning in 1995, groups of women at the brokerage firms Olde Discount Corp., Smith Barney, and Merrill Lynch filed lawsuits that cumulatively settled for hundreds of millions of dollars. In 2004, Morgan Stanley settled for $54 million in yet another gender case. In 2005, a second group of Smith Barney women filed another class-action lawsuit, settled in 2008 for $33 million.

A lone claimant like O’Brien runs the risk of having no witnesses to back up her allegations, but the women who came after her set their sights on getting certified as a class and derived strength from their numbers. The success of those suits provided potent motivation to employers to fight back against class actions. In the years since, many employers have taken to prohibiting employees from bringing such complaints at all. The law firm Carlton Fields Jorden Burt published a survey of 373 companies last year showing that 30 percent had arbitration clauses that precluded class actions, up from 16 percent in 2012 — the year after a key Supreme Court ruling that made it easier for companies to thwart class-action suits.

The class actions of the 1990s had sparked reforms at NASD, which until then had required anyone with a broker’s license to bring all employment-related disputes to arbitration. In 1999, the SEC approved a new rule that exempted employment discrimination cases, including those of sexual harassment, from arbitration unless both sides agreed to it.

Over time, brokerage firms simply came up with a workaround, forcing their employees to agree to arbitration at FINRA or other private forums for all claims, including harassment, as a condition of getting the job. “Several of the big players tie up significant numbers of women on the Street” with such contracts, said Pearl Zuchlewski, a New York employment lawyer. In the FIRE, or finance, insurance, and real estate sectors, 48 percent of firms have blanket requirements for arbitration, according to a study released this month by Alexander Colvin, a professor at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

- “To my knowledge,” a FINRA spokesperson said, “we have not brought disciplinary actions related to sexual harassment or gender discrimination.”

The combination of those company mandates and the difficulty of bringing class actions means many women on Wall Street land back at FINRA, where they seek justice one at a time.

By accident or by design, FINRA’s disciplinary, licensing, and arbitration divisions appear to protect harassers. Arbitrators have the option of referring egregious cases for possible disciplinary action, and some arbitrators do make such referrals in the cases of grave abuse of investors.

But we could not find a single case in 30 years in which arbitrators referred a sexual harassment case for enforcement.

We asked Ong, the FINRA spokesperson, whether FINRA’s enforcement division has ever pursued discrimination or harassment cases. “To my knowledge,” she said, “we have not brought disciplinary actions related to sexual harassment or gender discrimination.”

We sent detailed questions to Ong, including a query as to whether FINRA’s enforcement division has jurisdiction over sexual harassment by its licensees. She did not directly address the jurisdictional question, saying only that FINRA believes that harassment of any kind “has no place in the work environment,” and that its oversight of the broker-dealer industry “is based on our statutory mandate and focuses on investor protection and market integrity.”

In pursuit of that mission, FINRA’s enforcement division last year levied its largest fines on firms that had violated anti-money laundering rules or failed to report trades as required.

But FINRA’s enforcement division has sometimes addressed broader issues of workplace misconduct that fall outside the “investor protection” or “market integrity” categories, under a catchall ethics rule related to “high standards of commercial honor and just and equitable principles of trade.” In 2014, FINRA explicitly said that the “just and equitable” rule gave it authority to bring cases regarding business-related conduct “even if that activity does not involve a security.”

- “I get furious with FINRA. If they’d bring these cases and bar these pigs, we would not have this oppression in the industry.”

In a 2016 case, FINRA barred a broker for engaging in “abusive, intimidating, threatening and harassing” communications toward people in the office where he once worked, citing the rule. The broker had been fired from a branch office of a New Jersey brokerage firm, FINRA said, for “unprofessional conduct in the workplace,” including “threatening and abusive interaction with female employees”; after his termination, according to FINRA, he made vulgar and abusive threats to his former colleagues and even impersonated a New York City police officer in his efforts to intimidate a former co-worker.

In January of this year, FINRA’s enforcement division settled a case with Paul Betenbaugh, a former broker at Edward D. Jones, for having undermined Dalas L. Gundersen, a competitor and former colleague at the brokerage, by posting ads on Craigslist soliciting gay sex and listing Gundersen’s cellphone as the contact number. FINRA suspended Betenbaugh for three months and fined him $7,500. Though the case had nothing to do with investor protection or market integrity, FINRA cited its “just and equitable” rule to justify the action. “Harassing and abusive conduct violates the broad ethical principle” encompassed in the rule, a FINRA enforcement official wrote.

(Gundersen sued Edward D. Jones, Betenbaugh, and another Jones broker in 2015, alleging that they had executed a “smear campaign” to ruin his business, scoring a rare victory last year when a California Superior Court judge said the matter could remain in court despite a mandatory arbitration agreement. Garner, the California lawyer who represented Gundersen, said the case “involves wrongful competition of the worst sort.” Jones spokesperson John G. Boul said the firm continues to “vigorously defend” its position in the case; Betenbaugh’s attorney did not respond to a request for comment.)

Bill Singer, a veteran Wall Street lawyer who has represented plaintiffs and defendants in employment cases before FINRA, said if FINRA’s enforcement division were to take on harassment cases, “we could alter the culture of Wall Street.”

“I get furious with FINRA,” he said. “If they’d bring these cases and bar these pigs, we would not have this oppression in the industry.”

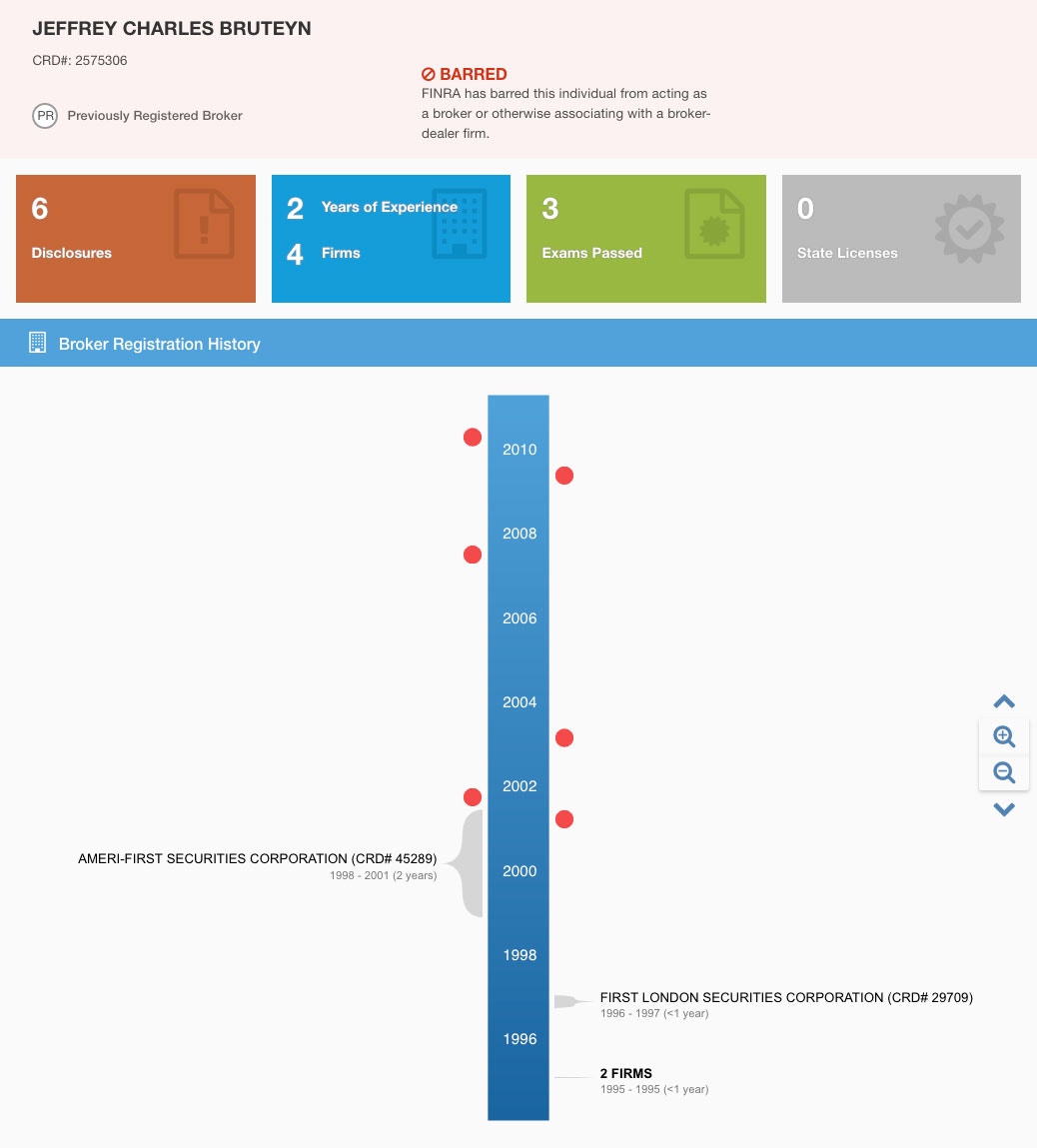

Broker Check website shows the record for Jeffrey C. Bruteyn, a former broker who is serving 25 years in federal prison for securities fraud.Image: BrokerCheck

Whether they are Main Street investors or Wall Street employees, women have an interest in knowing if a man in the industry has a history of sexual harassment. FINRA’s reporting policies, however, don’t make that easy.

We found that the public BrokerCheck records published by FINRA don’t make any references to the sexual harassment arbitrations that men have lost. Until we contacted FINRA on March 26 to ask about the incomplete records of former broker Jeffrey C. Bruteyn, who is serving 25 years in federal prison for securities fraud, there was no reference in BrokerCheck to a sexual harassment case that he lost.

Bruteyn’s records showed the fraud charge, four cases brought by securities regulators, and a customer dispute. But nowhere was there any mention of a July 2002 arbitration award that ordered him to pay $85,000 to a former female colleague for “intentional infliction of emotional distress and assault and battery.” (A case he’d lost only four months earlier — in which two investors alleged negligence, unauthorized trading, and other abuses — did appear on his report.) After being contacted by The Intercept, Ong said that FINRA had “just filed” an update to Bruteyn’s record, which now includes the sexual harassment case. Bruteyn did not respond to a written request for an interview.

The rare disclosures of sexual misconduct that do make it into brokers’ records arise from a FINRA requirement that brokers reveal all felony arrests, indictments, and convictions. In a 2013 enforcement case, FINRA barred a broker who had failed to disclose his 1988 guilty plea and conviction for aggravated criminal sexual abuse, a Class 2 felony. (The incident had taken place seven years before FINRA granted him a license.) By the time FINRA finally barred the man, the authority couldn’t even locate him: The enforcement division’s correspondence came back undelivered. By then, he had accumulated 11 customer disputes and had been out of the business for three years.

Yet even that disclosure rule is not always harshly enforced. We identified one case in which a broker who failed to disclose arrests and charges related to alleged sexual abuse got off with only a suspension. The case began when MetLife Investors Distribution Co. fired broker Henry Betances in 2015 after only two months, when the company found out that he hadn’t filed the required disclosures, according to his BrokerCheck record. FINRA’s enforcement division followed up with a settlement in 2016, noting that the state of Rhode Island had charged Betances with felony counts of third-degree sexual assault, breaking and entering a dwelling, domestic assault, and, in a second Rhode Island case, a felony count of child pornography. (All of these charges were later dismissed.) FINRA’s punishment: a $5,000 fine and a six-month suspension that ended in November 2016. He’s now free to reapply to work as a broker, though, according to his FINRA records, he has not done so.

- If women knew that a firm had a history of employing men who harassed women, many “wouldn’t want to go with that firm,” she said. “But unless the behavior is a felony, it’s not disclosed.”

FINRA’s licensing policies help keep sexual misconduct under wraps in other ways. The authority asks brokers detailed questions about their backgrounds in a form known as the U4, a 40-page synopsis that inventories all previous employers and previous addresses, and requires a listing of financial problems, including liens and bankruptcies. Most important, the broker answers questions about customer complaints, lawsuits, and criminal charges. But with the exception of the requirement to disclose felony indictments or convictions, there is nothing in the lengthy document that asks a broker to reveal other litigation or arbitration related to sexual harassment or other sexual misconduct. FINRA requires disclosure of misdemeanors only when they are “investment-related.” And it only asks brokers to reveal arbitration cases that are brought by customers and are investment-related.

“It’s a problem, believe me,” said lawyer Jane Stafford, who has represented defendants and plaintiffs in Wall Street cases for 35 years. If women knew that a firm had a history of employing men who harassed women, many “wouldn’t want to go with that firm,” she said. “But unless the behavior is a felony, it’s not disclosed.”

A woman walks by the New York Stock Exchange on February 22, 2018 in New York City.Image: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

We found that when women file complaints in FINRA’s arbitration forum, they rarely name their alleged harassers as respondents, typically opting to name only the firms. But in the eight instances we found with a named male defendant who lost his case, not a single one of the incidents was added to the man’s entry in BrokerCheck.

Consider Douglas A. Potter, who was the Santa Barbara, California, branch manager for Raymond James Financial until two days after we first contacted Raymond James about Potter’s record in March. As far as the public knows from FINRA’s public database, Potter has had only one black mark in his 48 years as a broker: a complaint that a broker Potter oversaw as branch manager had put a customer in unsuitable investments, a case that was settled for a fraction of the customer’s request.

A more comprehensive dossier kept by state securities regulators notes suggestively that, in 2005, Potter was “permitted to resign” from his previous job at A.G. Edwards & Sons, now part of Wells Fargo. That was related to an unexplained “violation of firm policy, no securities violations,” according to the records, provided by a state regulator. (FINRA and state regulators share a common database known as the Central Registration Depository; FINRA edits that information before posting it to BrokerCheck.)

Yet nowhere in either report does a 2007 decision by FINRA arbitrators appear — including the finding that Potter and A.G. Edwards were jointly liable “for damages for sexual harassment and retaliation,” as well as intentional infliction of emotional distress upon Sandra L. Crook, an A.G. Edwards broker. Crook had filed a claim against A.G. Edwards and Potter in 2005; the hearings, in 2006 and 2007, stretched across 22 days. The arbitrators ultimately decided that Edwards and Potter were jointly liable to pay Crook $500,000 in compensatory damages, $3 million in punitive damages, plus $418,262 in attorney’s fees. It was the single biggest harassment award we could find in the entire FINRA database, but it’s nowhere on Potter’s BrokerCheck record.

Neither Raymond James, Potter, his lawyer, nor Crook responded to requests for comment. We contacted Raymond James by email in mid-March about Potter’s record and asked if employing a broker with his profile was consistent with the company’s position on harassment in the workplace. Two days after our first inquiry, Potter’s records with state securities regulators were updated to say that he had just been terminated as part of “a reduction in force.”

A spokesperson for Wells Fargo said that the firm does not tolerate harassment and confirmed that the award was paid.

- “Some of these people who are harassing people harass them for a reason.”

Raymond K. Bramer is another broker who lost an arbitration related to sexual harassment — and whose BrokerCheck files show no signs of it. BrokerCheck says only that he’s had two customer complaints, both of which were settled, over his 44 years as a broker. Yet in 1996, his former employer, the brokerage firm Sutro & Co., filed an arbitration claim against Bramer seeking more than $180,000 for legal costs and “as indemnification for the full amount of the settlement” paid to Bramer’s former sales assistant over alleged sexual harassment. In 1997, the arbitrators ordered Bramer to pay $25,000 to Sutro toward the settlement that the firm had paid to the assistant.

Reached at his home office in early March, Bramer, currently a broker with Securities America, first said, “I’m a nice guy, I don’t harass anybody,” adding that the Sutro claim “was long ago” resolved through arbitration. When asked why his former employer would spend $180,000 in legal costs and a settlement on a frivolous claim, he said the firm just wanted to settle because such cases “go on and on.” Bramer then said, “Some of these people who are harassing people harass them for a reason.” Asked point-blank if he had harassed his colleague, he said, “I don’t think I did. Who knows?”

We looked up another broker who lost a harassment case, George M. Tamborello, on BrokerCheck. In 2011, Tamborello, who is no longer a broker, was found liable by arbitrators for sexual harassment and ordered to pay two female colleagues at Empire Financial Group compensatory damages totaling $1.1 million plus interest. Tamborello’s BrokerCheck records reveal two unrelated regulatory events, three customer disputes, and two criminal charges, including a 1993 guilty plea to criminal trespass — but nothing is mentioned about the harassment case. His more complete state records do reveal that he was “permitted to resign” during an investigation that included “claims brought by two former female employees,” but no details of the investigation are provided. Tamborello declined to comment.

Arbitrators rarely provide detailed reasons for the decisions they make, but in some case files, their attitudes about abusive workplace behavior are laid bare.

In a hostile work environment case brought by a Prudential insurance salesperson in the 1990s, Maher Shammas claimed that he’d been harassed and discriminated against on the basis of his national origin, religion, race, and gender. (His Grand Rapids lawyer, Mary A. Owens, said by email that co-workers teased him “because of his supposed sexual prowess/endowments as an Arab.”) One arbitrator in the case said in a dissent that the salesperson, a Lebanese immigrant who’d come to the United States at age 18, had been called “camel jockey,” “Moslem terrorist,” and “friggin’ foreigner” by his co-workers, who also ridiculed his Arabic accent. To mock him, his boss would get on his knees on the carpet in the office and invoke Allah. The man sunk into a major depression, the arbitrator said, and his wife testified “with powerful emotion about the withdrawal of her husband from their ordinary activities.” Yet the panel, without explanation, denied his claim. “It was a terrible decision,” said Owens. “We had many witnesses who supported our claims.” John M. Lichtenberg, a lawyer for Prudential, said that tape-recorded examples of the harassment, collected by Shammas, didn’t appear to support his most serious claims.

Another case provides a more vivid window into the attitudes of some arbitrators. The case began in 2013 when a married couple, Charles and Francis Prignano, accused their broker Michele “Mike” Pacitto of unauthorized trades and other malfeasance in a complaint filed with FINRA. Pacitto filed a counterclaim, alleging Charles Prignano had filed his claim “to shift financial responsibility” from investment decisions that Prignano himself had made. The tortuous case wound up including testimony that the customer, Prignano, had made unwanted sexual advances on Pacitto’s wife.

The arbitrators, in July 2014, denied the original claim by the Prignanos, making it clear that they did not think Pacitto was at fault for Prignano’s investment losses, and ordered Charles Prignano to pay the broker $150,000 in damages. Last July, an appeals court confirmed the award.

A worker walks into Morgan Stanley headquarters in Times Square September 18, 2008 in New York City.Image: Mario Tama/Getty Images

The most revealing insight into the arbitration is what followed. In a 2017 motion to vacate the decision, which referred to “alleged sexual advances or harassment,” Prignano referred to “a rogue arbitration panel” that had not taken its job seriously when hearing the case and had instead been entertained by the testimony about sexual harassment.

Transcripts of FINRA arbitration hearings are not publicly available, but the court records in this case provide a rare view inside that locked box, citing passages from the FINRA transcript. The motion quotes the arbitration panel’s chair, David L. Erickson, trying to put an end to the sexual harassment testimony. “OK, stop, stop,” he said. “We don’t want to hear testimony with regard to sexual harassment or character issues. We just want to deal with the facts.”

Arbitrator Steven M. Feder responded, “I’m kind of torn. I don’t think it’s really relevant, but it’s the most interesting part of the case,” setting off “audible laughter and side banter” throughout the room, according to the motion. A third arbitrator, Gerald K. Moore, cautioned his colleagues, saying, “Somebody will have to erase the laughter off the tape,” which set off another round of laughter.

Prignano said in an interview that the arbitrators were “yucking it up,” but Pacitto recalls that they were respectful to his wife, who was crying as she testified.

Of the three arbitrators, only Feder could be reached, and he declined to comment. Ong said that FINRA staff “investigates all concerns regarding alleged arbitrator misconduct,” sometimes recommending counseling or removal, but said FINRA doesn’t publicly comment on the outcome of such reviews.

Moore has not been assigned to a panel since the Prignano case, but Erickson and Feder have each been on four.

- “There is no doubt in my mind that every one of those arbitrators knew I was raped, but they couldn’t hang it on anything physical.”

We found that even harassment victims who win a case before FINRA can come away feeling overwhelmed and disheartened. Vescova, the former Southwest sales manager who alleged that she was raped at work, said the arbitrators who ordered $450,000 in payments on her harassment claim were sympathetic, even if they were unable to conclude she had been raped. But as a young woman in her 20s, she had understood little about how to protect herself when, according to a summary of her testimony, her boss “pinned her arms down, pulled down her stockings, and raped her” in the office one night. She said in an interview that the Manhattan commercial district was abandoned at the time, and no one heard her screaming. She said she didn’t call the police and didn’t even tell her mother, with whom she still lived. “There is no doubt in my mind that every one of those arbitrators knew I was raped, but they couldn’t hang it on anything physical,” Vescova said. “I didn’t go to the police because I was terrified,” she said, so there was no rape kit.

She said that during the eight days of her hearing, the brokerage firm was always represented by at least 10 lawyers — while she was represented by a tiny husband-and-wife team. She said that private investigators for Southwest dug into her life, coming up with unpaid parking tickets, and the firm’s lawyers threatened to embark on an expensive appeals process after the panel ruled in her favor.

Vescova said that other women she knew in the industry have hesitated to complain to FINRA, fearing that firms will file a defamation lawsuit or mark their licenses with trumped-up malfeasance. “I could name a dozen girls who were harassed and were going to file cases against other firms that never did.”

This article was reported in partnership with the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations, where Antilla is a reporting fellow. Research: Elena Mejia Lutz.