In recent years, the Texas Department of Public Safety has spent more than $15 million on two high-altitude surveillance planes. Typically flying at more than 2 miles above the earth, the planes are impossible to spot from the ground, leaving Texans in the dark about whether they’re being watched.

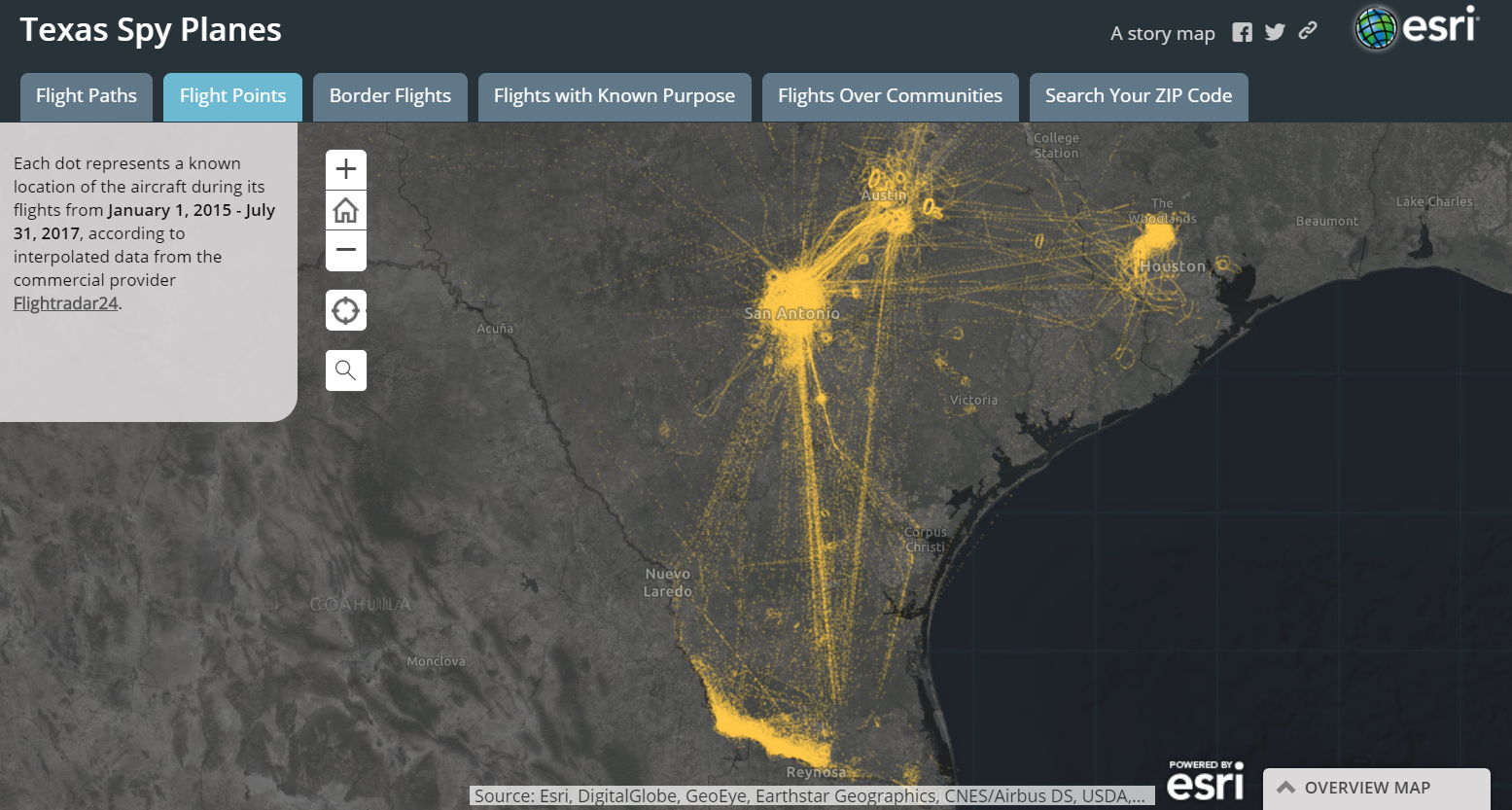

The planes, according to the manufacturer, are capable of tracking people and vehicles from several miles away and transmitting high-definition video overlaid with powerful mapping software in real time to analysts. By analyzing flight logs and tracking data, the Observer, in partnership with The Investigative Fund, now known as Type Investigations, found that from January 2015 to July 2017, during Operation Secure Texas, DPS flew these high-tech planes hundreds of times over wide swaths of Central and South Texas. The majority of the flights were concentrated over just two South Texas counties — Starr and Hidalgo — along the border.

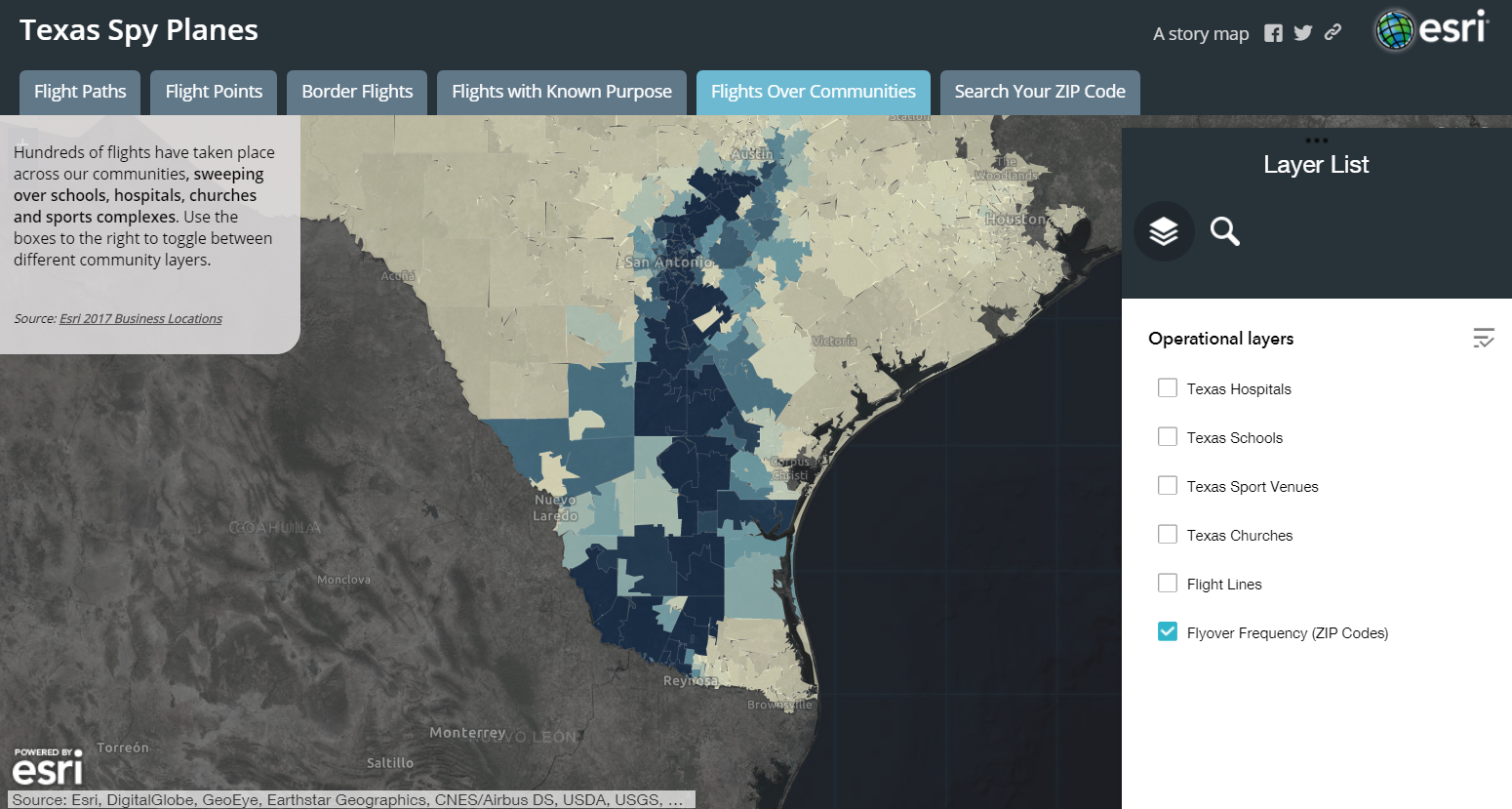

One plane is stationed near the border in Edinburg, in the Rio Grande Valley. The other is based more than 200 miles north, in San Antonio, which has experienced the highest number of inland surveillance flights. Many of the San Antonio flights were concentrated in the city’s southeast, where the DPS plane flew over Sam Houston High School, Martin Luther King Park and other locations. DPS planes also flew over Austin at least 38 times for criminal investigations or flight training. The planes circled Houston at least 20 times in connection with criminal investigations.

Two small border towns in Starr County — Rio Grande City and Roma — had the most flights per zip code of any place in the state. From January 2015 to July 2017, spy planes flew over Rio Grande City 357 times, making the border town of some 14,500 inhabitants the most watched city in Texas.

Noe Castillo, Rio Grande City’s chief of police, said he was aware that DPS operates surveillance planes, but he’d never asked for a plane’s help with an investigation. “Our city hasn’t used them,” he said. “We can make a request, but we’ve never had a situation where we needed it.”

Castillo said the crime rate in his city is lower than in many parts of the country. In 2016, the most recent year with FBI data available, Rio Grande City had only 17 incidents of violent crime. “I live 200 yards from the border and it’s a peaceful place,” he said.

In the neighboring town of Roma, population 10,265, DPS surveillance planes flew over the border city 274 times during the same time period. The planes flew over the city of Mission in Hidalgo County, home to the National Butterfly Center, 96 times.

The majority of the hundreds of DPS flight logs the Observer obtained through the Texas Public Information Act provide little information about what the planes were looking for. The purpose of the flights was often unlisted. In other instances, the records contain short explanations such as “border interdiction patrol,” or, in the case of non-border flights, “criminal transport,” “criminal photography” or “criminal investigation.”

The planes have also been used for purposes that are even further afield from what DPS Director Steve McCraw has described as a border mission, such as flying out of state to pick up fugitives. In February 2016, DPS sent one of its surveillance planes to Arizona to retrieve John Feit, a retired Catholic priest who’d been ordered to stand trial in Texas for the 1960 murder of a woman in McAllen.

In 2015, DPS sent a surveillance plane to rural Erath County, near Fort Worth, to fly over a corn field and confirm that marijuana was planted there. Days later, the Erath County sheriff conducted a raid on the field, but there weren’t any marijuana growers around and no arrests were made, according to police reports. The sheriff also abandoned attempts to seize the farmland because investigators couldn’t produceany evidence that the lienholder of the property was involved. DPS spokesperson Tom Vinger declined to explain why DPS was using one of its high-tech planes to chase pot growers, or how much the operation cost the agency.

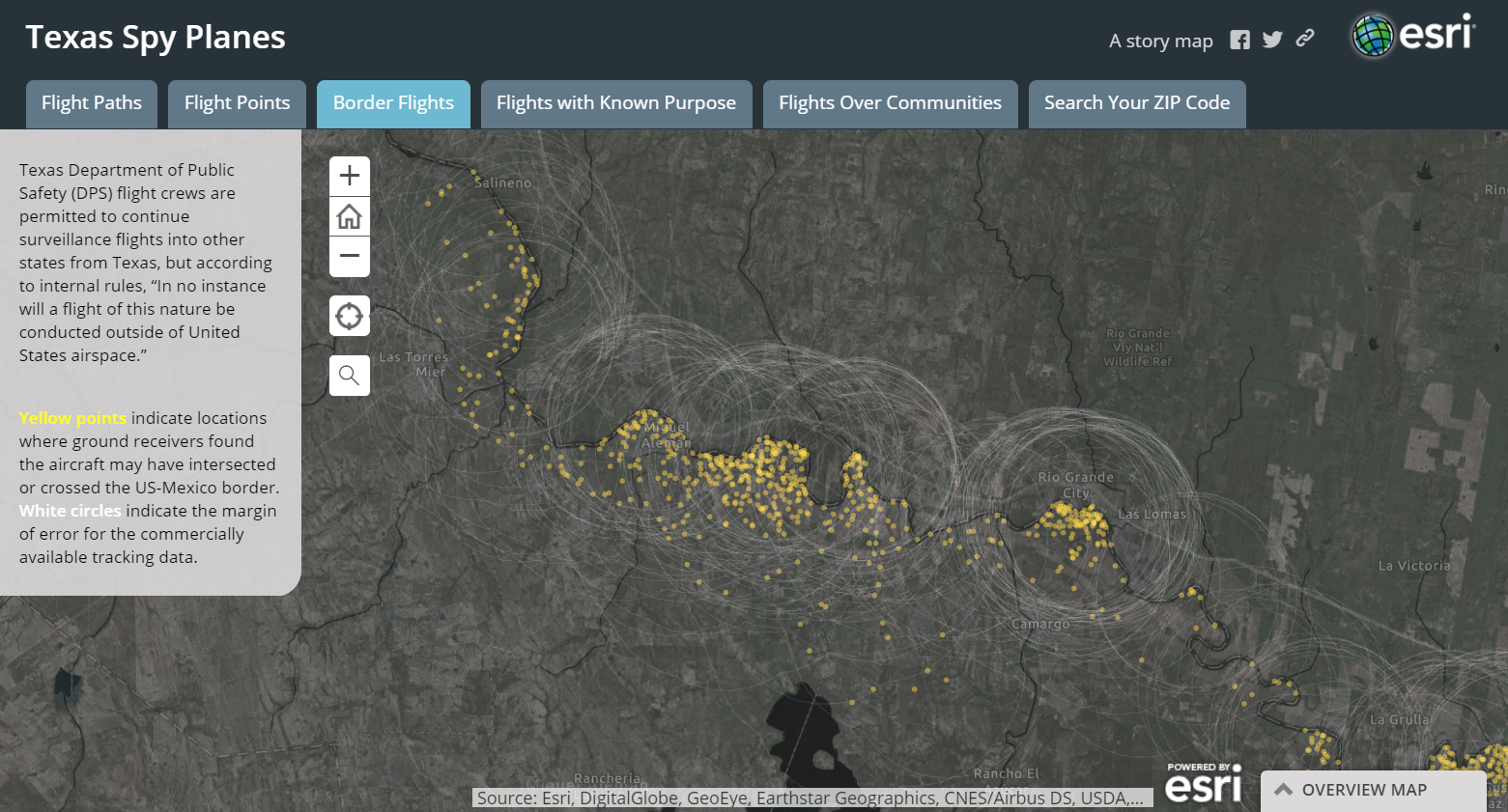

One of the most notable findings from our data analysis and mapping project is that DPS may be flying its surveillance planes over the border and into Mexico, despite department operating procedures that prohibit aerial surveillance missions outside U.S. airspace. The tracking data we obtained from Flightradar24, a commercial flight-tracking service, indicates that DPS planes crossed the Texas-Mexico border several times between January 2015 and July 2017, flying as far as 9 kilometers into Mexico. (Learn more about how we did the analysis and mapping here.) But because the otherwise state-of-the-art planes have used an imprecise transponder, the company triangulated locations based on data compiled from a network of ground receivers. Because those receivers are sparse near the border, Flightradar24 says, the tracking coordinates could be off by as much as 10 kilometers, putting those flights either inside the U.S. border or deeper into Mexico.

Vinger responded to the Observer’s findings of potential cross-border flights by email, saying they were “incorrect” and citing “accuracy issues with publicly available software to track planes.” Vinger also wrote, “There have been no complaints or reports made to the department by the federal government in Mexico or by our federal government.”

But there is some compelling evidence that cross-border surveillance might be occurring. In a contract document obtained by the Observer through a public information request, Pilatus, the company that built the planes, details their surveillance capabilities, listing “searchable satellite and street map layers for North America as well as data vectors for Mexico extending into the country approximately 10 miles from the border.”

Aviation tracking data obtained from the commercial firm Flightradar24 show Texas Department of Public Safety planes crossed the Texas-Mexico border several times between January 2015 and July 2017, flying as far as 9 kilometers into Mexico. But because the planes used an imprecise transponder, the tracking coordinates could be off by as much as 10 kilometers. DPS operating procedures prohibit aerial surveillance missions outside U.S. airspace. Click to learn more.

A 2015 Austin American-Statesman story uncovered a report created in 2010 by former DPS contractor Abrams Learning and Information Systems, a private defense firm, that detailed DPS surveillance, using older RC-26 planes, on the Zetas cartel in Mexico. The agency allegedly shared information with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Mexican military. The section detailing the collaboration in the report was preceded with the warning, “Need to be careful here as we are admitting to spying on Mexico.”

DPS denied to the Statesman that it had conducted spying operations in Mexico. The Observer asked ICE whether it had worked with DPS on surveillance flights in Mexico, and the agency offered only a brief written response: “ICE officials can neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation or operational activity.”

DPS said the planes have state-of-the-art ADS-B transponders, which could allow for more accurate flight tracking, but according to Flightradar24, DPS hasn’t activated the transponder in the plane that regularly patrols the border. Vinger wrote that each DPS aircraft also uses GPS mapping that is “accurate within 3 meters to assist the crew with situational awareness at all times — this is especially true near the Texas-Mexico border.” DPS declined to release that tracking data.

Two high-altitude surveillance aircraft with an initial combined price tag of $15 million have conducted hundreds of flights over select areas of the border. Operated by the Texas Department of Public Safety as part of its ongoing push to secure the border, the aircraft have flown over schools, hospitals, churches and more in Texas. Click to learn more.

If DPS is crossing into Mexico to conduct surveillance, it’s highly unusual and possibly dangerous, said Raúl Benítez-Manaut, a professor of geopolitics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The border is already crowded with Mexican and American federal law enforcement agencies, and accidents or misidentification are real risks, he said, especially if the Mexican military is not notified. Drones are one thing, Benítez-Manaut said; if they crash or get shot down mistakenly, at least there’s no one onboard. In 2010, for example, a mini Orbiter unmanned drone operated by the Mexican government crashed in a backyard in El Paso — and no one was injured. But a piloted plane is far more risky, Benítez-Manaut said. “The Mexican Air Force could think the plane belongs to a drug-trafficking organization and shoot it down.”

A spokesperson for the Mexican embassy in Washington, D.C., said by email that Mexican authorities “have no register of such aerial surveillance activities.” She added that the United States is obligated to conduct itself with “strict respect for the territorial and jurisdictional sovereignty of the Mexican State.”

After the purchase of the first spy plane in 2012, McCraw lobbied for a second plane in a letter to Governor Greg Abbott, explaining that it would be used as a “force multiplier” on the border. “During the past two years,” McCraw wrote, “the Pilatus has flown 1,585 hours, participated in 201 investigations, performed 772 agency assists, directed ground personnel to interdict 3,464 persons, and located 20 lost persons.”

According to the agency, it costs $474 per hour on average to operate one of the planes. Vinger said in an email that the agency did not track whether any of those 3,464 apprehensions led to an indictment, prosecution or conviction.

Since the agency publicly releases so little information, it’s impossible to verify McCraw’s numbers. The Legislative Budget Board, a joint committee that reviews state agency spending, issued a critical report in 2015 that found “the lack of consistent reporting on border security” makes it difficult to “evaluate the strategic value” of Texas’ spending.

Victor Manjarrez Jr. worked for the U.S. Border Patrol for more than two decades, including as sector chief. He’s now associate director of the Center for Law & Human Behavior at the University of Texas at El Paso, where he has observed DPS’ growing role in border security with skepticism. “With what the state has done, I think we need to step back and say, ‘Is it worth the value?’” Manjarrez said. The spy planes strike him as little more than “some very expensive toys.”

Flights conducted by the Texas Department of Public Safety’s two high-altitude surveillance aircraft are mostly concentrated in the Rio Grande Valley, where one aircraft is stationed. The other aircraft is kept in San Antonio. Click to learn more.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection already operates an aerial surveillance program using unmanned drones, which has cost taxpayers well over $360 million since the program started in 2004. The program has frequently run into problems. At least two drones have crashed on patrol, and expenditures have been hard to account for, according to a withering 2015 report presented by John Roth, former inspector general for the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees CBP. Roth recommended halting the purchase of drones until the agency could establish metrics for success. “They never established any performance measures, so they can’t tell whether the program is a success or not,” Roth told C-SPAN after releasing his report.

It’s a criticism that could easily apply to Texas. “They never did set out in the beginning what they hoped to accomplish at the end of the day,” Manjarrez said of DPS and state legislators who have signed off on one expensive border security operation after another. “Now they sure did use the word ‘border security,’ but, by God, you could ask 50 different people what that means and get 50 different responses.”

During his time in the Border Patrol, Manjarrez recalled, part of the strategy was to make the agency’s fleet of planes and helicopters visible at the border, on the theory that the sheer show of force might deter people from trying to cross illegally or smuggle drugs into the country. “The whole point is to have that visual deterrence,” he said. “But how are you doing that with a high-altitude spy plane that no one can see?”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations, where Melissa del Bosque is a Lannan reporting fellow.