You have seen 500 Old Country Road in Garden City even if you have never actually driven by. It is the kind of anodyne office building that one finds along just about every highway in America—three stories of tinted glass and grey concrete, with the requisite landscaping of tidy hedges and close-clipped grass and a wrap-around parking lot. There is a strip mall across the street with a Stop & Shop and a Barnes & Noble. It looks like where you’d go to get your teeth cleaned or secure title insurance. It does not look like a locus of political influence in New York state. But that is exactly what it is. In the past four years, more than half a million dollars have poured out of that building and into New York state’s political campaigns—the vast majority of that money linked to Breslin Realty, a shopping-center developer whose name decorates the front of 500 Old Country Road.

But none of the donations came from Breslin Realty itself. They came instead from a network of 22 limited liability companies that, though all controlled by Breslin, legally operate as separate individuals and so, under New York state’s campaign finance laws, can each donate the individual maximum to political campaigns.

The 22-year-old “LLC loophole” has been a bête noire for government-reform advocates for years because it gives these companies the same rights as people. In fact, it allows firms to wield far more power than individual donors by using affiliated LLCs to write multiple checks to candidates. What’s more, while the beneficial owners of the LLCs make themselves known to the candidates themselves, the structures are so opaque that they are often impossible to penetrate for the voting public. New York’s LLC loophole—similar ones exist in five other states—defeats a basic function of the modern campaign-finance system, which is to make the source of candidates’ money transparent.

Campaign finance filings maintained by the state Board of Elections offer only limited clues on who’s behind an LLC. BOE records typically include just a mailing address and the legal name of the entity, which might be as obscure as “1093 Group LLC.” There’s no easy way to find out who is behind that name.

The Department of State, which registers corporations, doesn’t track or provide information on LLC ownership. And yet as a candidate, says former Governor Eliot Spitzer, “You always know who is behind an LLC. You know who it is. There’s no mystery in that world.”

The loophole came up during the recent trial of Joseph Percoco, a former top aide to Andrew Cuomo who was convicted of accepting bribes from Competitive Power Ventures, a firm that had sought lucrative state contracts. Star witness Todd Howe said he had told another firm, COR Development Company, to send donations to Cuomo’s campaign—but to do it using multiple LLCs—and to avoid sending checks from LLCs whose name resembled COR’s. The loophole also played a prominent role in the recent corruption prosecutions against former State Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos and former Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. LLCs were also caught up in the state and federal investigations of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s fundraising efforts for state senate candidates in 2014. (Charges were never filed against the mayor.)

With four major public corruption convictions so far this year in the Empire State, political reform is an issue that outsider candidates are hammering as the September 13th primary approaches. There are growing calls, even among establishment candidates, for public financing. The LLC loophole figures prominently in the case for bold change.

City Limits and The Investigative Fund analyzed campaign finance records from the state Board of Elections over the past 19 years to catalogue the sources and recipients of LLC money, and then consulted legal documents, corporate information, and lobbying records in an attempt to identify who the donors really are and what their policy priorities may have been. We also spoke with political professionals, including former candidates, to learn how LLC fundraising works.

Among our findings:

- Since becoming a vehicle for campaign donations in the late 1990s, the LLC mechanism has generated at least $188 million in donations. The amount of LLC activity has increased steadily from cycle to cycle.

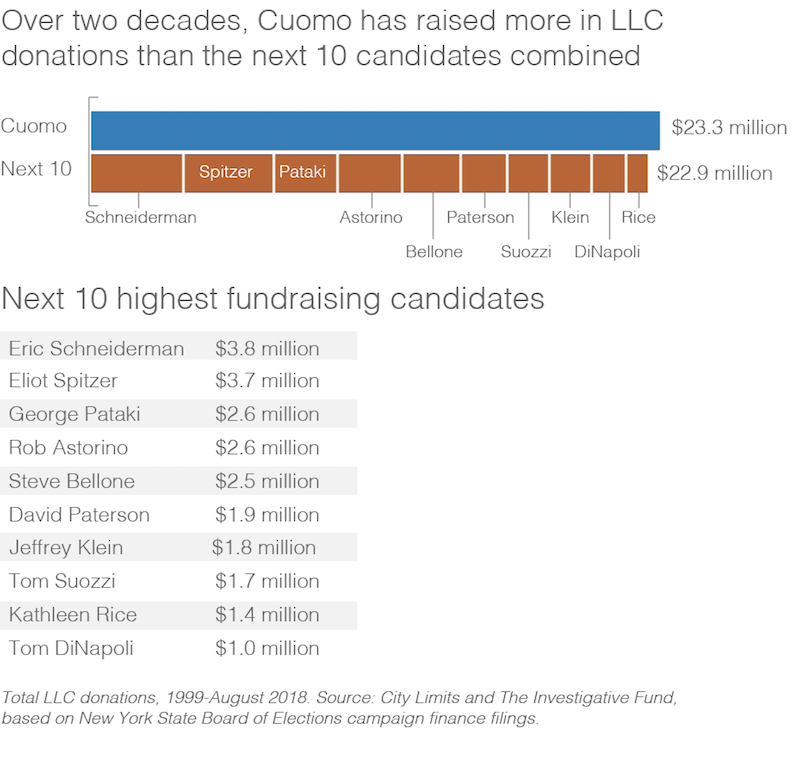

- Some 6,600 candidates and committees have received LLC donations during that time, from candidates for town supervisor and judge to those seeking state senate seats and the governor’s mansion. But just 35 candidates or causes soaked up nearly half of the money. Of these, Cuomo reigns supreme: Combining his campaign for attorney general in 2006 and his three runs for governor, Cuomo has received roughly one of every eight dollars donated by LLCs.

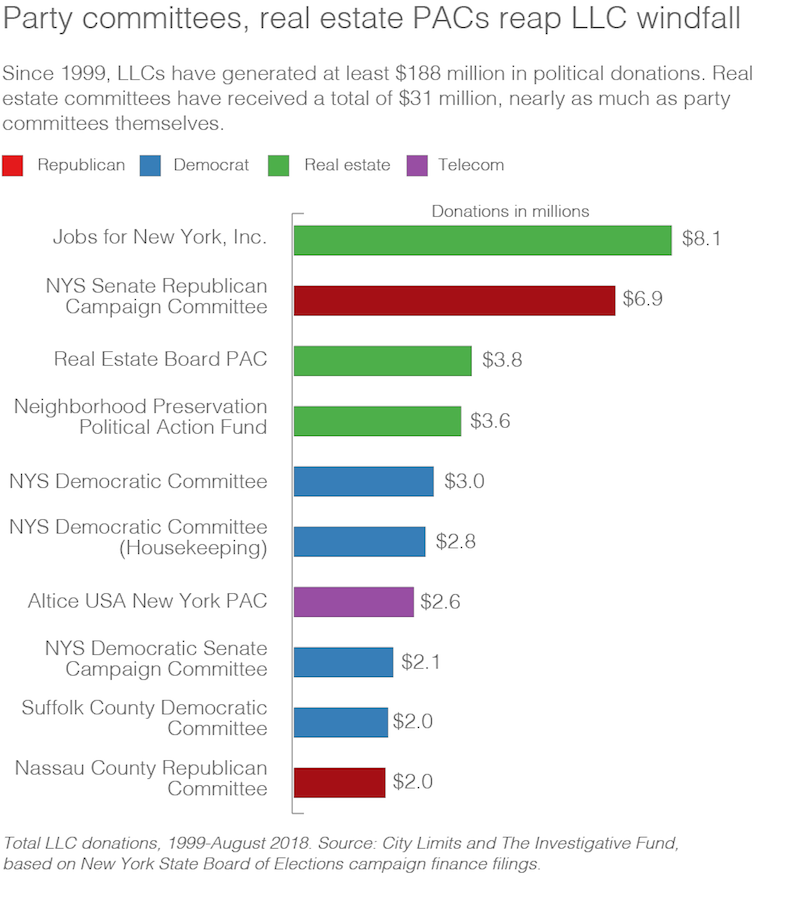

- Political action committees and party committees receive huge amounts of LLC money—among the top 35 recipients of such money since 1999, PACs took in more than candidates. That raises additional concerns: When people donate to PACs through LLCs, the original donor is even more hidden.

- While real-estate LLCs were the most common givers, LLCs tied to cable companies, beer distributors and even lobbyists were also important players.

- LLCs concentrate power geographically. Of the more than $50 million in LLC money donated so far this cycle, roughly a tenth of it came from just 10 addresses. And more than a fifth of that LLC money came from just 10 ZIP Codes, four of them in Midtown Manhattan.

500 Old County Road in Garden City, a major source of LLC campaign donations.Image: Jarrett Murphy

Cuomo called on legislators in his 2018 state of the state speech to “increase trust by closing the LLC loophole,” as he had in similar years. Despite those calls, the loophole remains intact. Given that the governor has taken on the National Rifle Association, passed same-sex marriage, forced New York City to fund more transit repair work and accomplished other heavy political lifts, it is notable how little success he has had closing a loophole that primarily benefits him.

Two decades of darker money

Limited Liability Companies date to 1977, when Wyoming created a kind of company that—like a corporation—limited the liability of owners and, like a partnership, would face no separate corporate taxes: Profits would be simply taxed as income of the parent company or individual owner. The ability to shield a larger poor of assets from a lawsuit related to one part of your business operation was obviously attractive: If you were a property owner with 100 buildings and a brick from Building 1 fell and hit someone in the head, would you rather a plaintiff sought damages from all the assets in your 100-building portfolio, or just from Building 1?

Wyoming’s innovation only affected firms incorporated in the Cowboy State, and only covered state taxation. For more than a decade, LLCs remained an obscure experiment as the Internal Revenue Service sent conflicting signals about how it would tax the entities, finally announcing in 1988 that it would treat them as partnerships. That ruling meant LLC income could be reported on the owners’ individual tax returns, and would not be subject to corporate taxation. Other states quickly raced to pass their own LLC laws, and LLC registrations exploded. New York was among the last to pass a law, in 1994. Tallies of the total number of LLCs are shaky, but one estimate in the Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law in 2009 held that, nationwide, 4.9 million new LLCs were formed just from 2004 through 2007.

In New York, at least, the legislature addressed the questions of LLC taxation and corporate liability without taking on the potential political ramifications of allowing business empires to operate multiple legal vehicles. That fell to the state Board of Elections, which in 1996 ruled that every LLC would be deemed independent when it came to how much they could spend on politics but also that they could do so as “persons.” That small legal quirk had torn a massive hole in the state’s campaign finance regulations.

- “I think it can be seen as the granddaddy of our biggest campaign finance and corruption problems”

In New York, a corporation is capped at $5,000 in political donations per year—that’s an aggregate, across all races. A person, however, faces no aggregate limit and can give far more to each state candidate than any real person can to federal office-seekers. She, he or, in the case of an LLC, it can give for a general election race up to $44,000 to each candidate for governor, $11,000 to each candidate for state senate, $4,400 to every assembly hopeful and $109,600 to each party committee—with separate, smaller limitations for contributions during a primary run. Again, those are only the limits on what each LLC can give; the numbers get far bigger for companies that control dozens of them.

“I think it can be seen as the granddaddy of our biggest campaign finance and corruption problems,” Susan Lerner, executive director of the reform group Common Cause New York, says of the LLC loophole, “because it allows the real-estate industry, in particular, to get around one of the few, effective limits in our campaign finance law, which is the corporate limit of $5,000.”

“The LLC loophole has the negative wallop that it has on our governing system,” she argues, “because it’s combined with sky-high contribution limits.”

In its 1996 decision, the state elections board was following the lead of a 1995 opinion by the Federal Election Commission, five out of six of whose commissioners were then appointees of Republican presidents, that when it came to federal campaign finance laws, LLCs were persons. However, the FEC, now with three Bill Clinton appointees, reversed itself in 1999, ruling that LLCs would now be treated as corporations or partnerships, depending on the specifics of their tax status—but never as persons. While New York City’s campaign finance board banned LLC contributions in 2007, the New York State Elections Board never adjusted accordingly.

By the 2000s, as LLCs began to dominate in real estate, they became a growing source of campaign contributions, according to former State Assemblyman James Brennan of Brooklyn. “It became this great generator of campaign cash.” They have become particularly important in gubernatorial campaigns, where, since 1999, they’ve made up more than $31 million, or about 12 percent of total donations.

While tracing the forces behind LLC donations can be difficult for citizens and journalists, the people doing the asking—candidates, or more likely, the professional fundraisers they employ—are not in the dark at all. “The universe of very wealthy real estate operators is fairly small,” Brennan says. “There’d be a circle of people who know each other. They know the game.”

From the candidate’s perspective, says a veteran political operative who works for one very active donor who controls multiple LLCs, LLC giving is not any different from any other donation from an individual or a corporation or a PAC. “Somebody calls and says, ‘Would you make a contribution?’ Then they send a piece of paper that lists the limits. And you decide how much to give.”

Spitzer, who won statewide elections for attorney general in 1998 and 2002 and governor in 2006, concurs. “You know who the LLCs are because LLC ownership goes back to a building,” he says—say a building with a particular street address. “On the fundraising side, if the fundraiser calls over to [a real-estate LLC], he says, ‘How many LLCs do you have?’ ‘Oh well we’ve got 10. We’ve got 20. We’ve got 30.’ And [the fundraiser] says, ‘Well, you can contribute from all of them. Pick five and contribute $20,000 from each of the five.’ If you want to do $100,000, that’s how you do it.”

Former Gov. Eliot Spitzer, who raised millions from LLCs, tried to close the loophole in 2007 but was not successful.Image: Timothy Krauser/Flickr

Fundraising consultants, according to the veteran operative, typically divide the world into buckets and direct candidates to raise from each one: Their family. Their neighbors and college buddies. People whose past giving indicates compatible politics. People who despise their opponent. And also, “Here are the people who give money and live in the district or have buildings in the district.”

While taxi companies, fight promoters and beer distributors all operate LLCs, and make political donations through them, real estate dominates LLC political giving.

“People know who the donors are,” Spitzer says. “They know who in the real estate sector gives or is likely to give or feels obligated to give. So you pick up the phone to the major companies and say, ‘Look, this, that or the other thing. Do you want to be supportive? Of course you do.’“

Spitzer raised $41.4 million for his governor’s race in 2006, including some $3.1 million in LLC money—the ticket 2006 ranks second of all time among New York state campaigns for amount of LLC money received, according to City Limits’ calculations. But, he points out, “the law permits it.”

The law is so loose it could permit far worse. “I do remember that at one point people said, ‘We can create new LLCs to give to you,’“ Spitzer says. “We said no—it’s got to be a real, operating company.”

Many beneficiaries—but one looms largest

LLCs don’t show up in state campaign finance filings until 1999, the first year of the 2002 election cycle in which Governor George Pataki won a third term as governor. In that election, LLCs donated $7.1 million. Four years later, when Spitzer ran for governor and Cuomo for attorney general, LLCs gave $19.9 million. During the next cycle, when Cuomo was elected governor and Eric Schneiderman, a prodigious LLC fundraiser in his own right, was elected attorney general, LLC contributions rose to $43.7 million. By the last state election, in 2014, LLC giving had reached $67.3 million.

As of mid-August, $50.4 million in LLC donations have been logged already for 2018.

Image: Alex Newman

Candidates who top the list of the all-time LLC recipients include Schneiderman, Spitzer and Pataki, as well as former Westchester County Executive Rob Astorino (who ran for governor as a Republican four years ago), Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone, and Governor David Paterson (during his aborted 2010 re-election campaign). The wealth has been shared: Some $21.2 million in LLC donations has gone to Senate candidates since 1999.

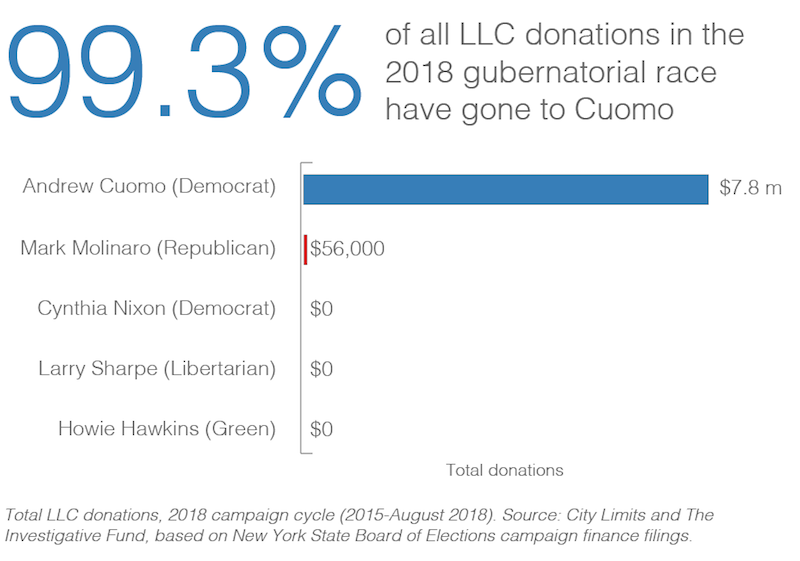

Cuomo, however, stands head and shoulders about the rest, with his total LLC haul greater than that of the next 13 candidates put together. Over this current cycle, LLC donations have comprised 22 percent of Cuomo’s fundraising, or $7.9 million out of his $35.6 million haul.

Another portion of LLC largesse is showered on party committees. Republicans and Democrats split this money pretty evenly, with the respective state committees and their senate-focused campaign committees—all of which can funnel their fundraising to individual candidates without limit—cleaning up.

Then there are the PACs. Second only to Cuomo in LLC donations, at $8.1 million over the past five years, is the Jobs for New York PAC, which the Real Estate Board of New York, an influential force for developer interests in the city, launched in 2013 to influence City Council races. The Real Estate Board has also attracted $3.8 million to its eponymous PAC. And real-estate interests are further advanced by the LLC fundraising of the Neighborhood Preservation PAC, a landlord-funded entity that has opposed strengthening rent regulations. Pepsi’s PAC—the soda giant focused its lobbying on the New York City Council, which has weighed a crackdown on sugary drinks—is also a big recipient.

Image: Alex Newman

Multiple checks from the same address

Another major recipient is the Altice USA New York PAC, which is based at the offices of Cablevision and is funded by a host of Cablevision subsidiaries: Cablevision of Warwick, LLC; Cablevision of Hudson Valley, LLC; Cablevision of Oakland, LLC; Cablevision of New Jersey, LLC; and Cablevision of Rockland/Ramapo, LLC. Altice has spent $137,000 in campaign donations this year, sending $21,000 to Cuomo’s lieutenant governor, Kathy Hochul, $15,000 to attorney general hopeful Letitia James and $10,000 each to the committees dedicated to keeping the state senate red and the state assembly blue.

These Cablevision subsidiaries have also showered donations on the governor directly. From April to July 2018, Cablevision of Monmouth, LLC, sent Cuomo checks totaling $42,500. From May 2017 to July 2018, CSC Holdings LLC sent him checks totaling $55,000. And in July 2017, Cablevision of Warwick LLC dropped another $50,000 on the governor. In recent years, according to lobbying records, Cablevision has taken an interest in bills establishing internet privacy, regulating the transfer of cable systems, and barring internet service providers from disclosing users’ private information without written approval. None of these issues are resolved—and are likely to be on the table in Albany for years to come.

- Top addresses for LLC giving According to the data from the New York State Board of Elections, the 10 sites on this map were the top points of origin for LLC campaign donations so far in the 2015-2018 election cycle. Zoom out to see additional locations.

The LLC loophole has allowed other industries to blast past the $5,000 aggregate limit in New York on corporate campaign donations. Take Manhattan Beer Distributors, which supplies bars in a 15-county area, which has made 231 contributions this year to two PACs, five party committees and 90 individual candidates. Its total generosity: $498,600. In the past year, Manhattan Beer lobbied against a bill that would have imposed a tax hike on alcohol, and lobbied heavily on the state budget as well.

The gaming concern Genting New York used LLCs to give more than half a million dollars, including to a gambling PAC, the governor, and committees associated with the Republicans, Democrats and the now defunct Independent Democratic Conference, or IDC, since 2011. Genting, during this period, weighed in on no fewer than 122 pieces of legislation, including a bill that would require the state Gaming Commission “to consult with host communities” before siting any new Video Lottery Terminal facilities in Suffolk County.

But the opacity of LLCs can make some equally massive donations hard to trace.

For instance, there’s RXR Realty, a developer and property owner. RXR is based at 625 RXR Plaza in Uniondale, on Long Island. Thirteen different entities registered at that location—most, but not all, with RXR in their names—have made a total of $330,000 in contributions to 13 candidates and three committees over the current cycle. The bulk of it went to Cuomo: $230,000 split among five checks from five different entities. Two $65,000 checks went out from different LLCs on the same day in May 2017, one from a firm listed as Gabeli Holdings, LLC, that does not appear to be registered with the state—at least with that spelling. Like any developer, RXR would likely have an interest in tax breaks, development subsidies, land-use policies and the like—but it’s hard for voters to know if that’s what’s driving these donations, because it’s hard to know exactly where they came from. (RXR declined to comment for this story.)

- “You’d say, ‘Guys I’ve been on your side. And I need help.’ That was the pitch to make. And it was an appropriate pitch to make.”

According to the veteran operative, these hidden donors are never asking for a quid pro quo, which would be illegal. “I’ve been on the receiving end of millions of dollars of contribution asks and I have never made a contribution with a specific—or any vague—ask in mind. Nor has anyone ever offered that,” he says. “It’s never, ever a direct thing. The people who do direct things go to jail. Or they should go to jail. ”

Recent corruption trials, of course, offer evidence of multiple instances of donations or gifts being linked to firms seeking or getting favorable treatment. But the day to day of money politics is typically far subtler. “Why in hell does anybody give money?” asks Richard Brodsky, a former assemblymember from Westchester. “Because they like what you do. [Incumbents] work their district and people like that and then go out and vote for them and give them money.”

Spitzer says he and his team often reminded donors of his past work. “You’d say, ‘Well, you know, I am the one who has been fighting for your issues for the past 10 years.’ If you were sitting down with environmental groups or groups supporting same sex marriage, where I was the only one supporting it, you’d say that. And you’d say, ‘Guys I’ve been on your side. And I need help.’ That was the pitch to make. And it was an appropriate pitch to make.”

The improper reasons to give, Spitzer says, “are too obvious to state. But it’s that you want the access or you feel obligated otherwise you won’t get the contacts to get a deal done or you think you’ll get favorable treatment.”

Many firms active in LLC giving reveal some of their policy priorities in their biannual lobbying disclosures. But companies vary in how specifically they disclose the targets of their lobbying—some mention specific bills, but others offer only vague descriptions. And many ideas in Albany fade as legislative proposals only to be incorporated into the budget, which, because of its size and the opaque process that surrounds it, makes unmasking the political interests behind LLC largesse even more difficult. Companies might disclose that they lobbied on the budget, but that offers voters next to no information about their specific interests.

The expanding role of the state budget could be one driver of the massive increase in LLC campaign donations. A 2004 court ruling, Silver v. Pataki, appeared to give the governor broad latitude to insert policy changes into the budget. The legislature would normally be able to vote on such policy changes—if they were individual bills. But when they are part of the budget, lawmakers can face an all or nothing choice: Either veto the entire budget, risking critical items such as school funding, or swallow the policy changes buried there and approve the budget as is. Other states may have flawed budget processes, but the amount of taxpayer money on the table in Albany makes for far higher stakes than just about anywhere else: It is one of only three states—the others are Texas and California—whose annual budgets exceed $100 billion.

- “Andrew could have done it years ago if he cared, but he doesn’t want to because that’s where he gets his money.”

That budgeting power could explain why so much LLC money has landed with Cuomo, Brodsky says.

“The big issues are decided in the budget these days,” says Brodsky, now a senior fellow at Demos. “Take the tax break system. Take economic development projects,” he says. “The big money people are giving their money to governors’ races.”

Overturning Silver v. Pataki, Brodsky argues, would be a major step toward fixing the state’s broken campaign finance system, as it would remove a major incentive to shower donations on an unusually powerful executive.

Under New York’s customary three-men-in-a room budget bargaining system, the leaders of the Assembly and Senate also wield significant power. That could be why the party committees, which maintain Democratic control of the former and Republican dominance of the latter, are also among the top LLC beneficiaries. But they still receive significantly less than the man in the governor’s mansion.

Reform has a shot

During his 2010 campaign for governor, Cuomo pledged to tackle the LLC loophole, and he has raised the issue on multiple occasions since. In 2016, he proposed a suite of bills eliminating LLC donations to races for particular offices—offering the legislature a chance to bar gubernatorial candidates from receiving the dark money without picking their own pockets, if they chose to exempt the legislature. Of course, Cuomo was proposing to bar LLC donations going forward—not to give back the millions he’d banked from them over his career, millions he’d have the ability to deploy to his next race against candidates who, restricted by any new law, would have a difficult time trying to catch up. As the late Wayne Barrett pointed out in a Daily News editorial at the time, “This masterstroke left [Cuomo] looking like he was falling on his sword when he was, even if inadvertently, plunging one down the throat of his competitors.”

Again in this year’s State of the State address, Cuomo called for the loophole to be closed. But evidence that he has made it a priority is slim. One exhibit is a letter the governor wrote in April to State Senator Simcha Felder, a Brooklyn Democrat who has given the Republicans a majority by caucusing with them, in an attempt to get Felder to caucus with his party instead. “Ethics reforms, including campaign finance reform, closing the LLC loophole and banning outside income, would be significant advancements,” possible only if Democrats controlled the Senate, Cuomo wrote.

And Cuomo’s campaign insists that his commitment to the issue is real. Spokesperson Abbey Collins responded to a query by email saying, “The Governor will continue to lead the fight to close the LLC loophole and is 100 percent focused on flipping the State Senate and forming a Democratic Senate majority so we can enact comprehensive campaign finance reform.”

“I certainly can’t opine as to what’s in the governor’s mind—whether he’s sincere, or not sincere” about closing the loophole, says Lerner. “What we can look at are the results. And in a powerful governor’s system, it’s striking that there are numerous reform issues including the LLC loophole which the governor professes to support and yet somehow or another never manages to change.”

Spitzer says he was working on a similar deal with state legislative leaders to close the loophole back in 2007, but that effort fell apart. Andrew could have done it years ago if he cared,” Spitzer says, “but he doesn’t want to because that’s where he gets his money.”

The governor is not the only pivotal player: Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan, a Republican and a recipient of some $154,000 in LLC donations since 2015, has called the LLC issue “a red herring” and suggested that the real problem is a lack of campaign enforcement. When the Brennan Center in 2015 sued to try to force the state Board of Elections to reverse its 1996 ruling that created the loophole, the state Republican Party joined the case as an intervenor to oppose any change. (A lower court and an appeals court dismissed that case, partly on the grounds that it was a matter for the board or the legislature, not the courts. The Brennan Center is considering further appeals.)

Several Democrats running in state senate primaries this year, including Julia Salazar and Robert Jackson, have named closing the LLC loophole as a priority if they are elected.

Cuomo, however, remains an X factor in any drive to end it. This is almost certainly his last election in New York State. Whether or not Cuomo seeks national office in 2020, it seems unlikely that Cuomo would go back to state voters in 2022 for a fourth term, as his father Mario did in the very painful defeat that ended his political career. And the younger Cuomo has shown a willingness to enact reforms when they no longer pose a threat to him: After the Committee to Save New York spent $16 million during his first few months in office to back the governor’s agenda with TV ads, while disclosing nothing about its donors, Cuomo signed a bill increasing transparency for such nonprofit lobby groups. The committee, no longer of much use, effectively went out of business. Come Election Day, closing the LLC loophole will no longer hurt Cuomo personally; all it could do is burnish his legacy—or his reputation as he pursues other prospects.

Image: Alex Newman

Lerner says that regardless of what role Cuomo might play, “there are more activists watching. There are more voters who want to actually look at candidates’ voting records, when they’re incumbents, and hold them accountable.”

Brodsky argues that the LLC loophole be treated as one corrosive symptom of the larger problem it reflects, a problem that has accelerated dramatically since the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United: that of giving companies the human right to political expression through their financial clout. “The best way to stop the problem is to adopt a policy in New York that stops corporations from behaving like they are voters,” he says. “Our democracy is for people.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Wayne Barrett Project at The Investigative Fund, now known as Type Investigations.