The El Paso Processing Center, informally known as the Camp, is a sprawling, walled-in compound of low-lying cinder-block buildings and trailers tucked between the landing strip at El Paso International Airport and the Lone Star Golf Club, a public course that sits just across the street. The Camp houses around 800 immigrants at any given time—some awaiting deportation, some awaiting their hearings or appeals. Some pass through for a day; others stay for years.

Wassim Isaac, a thirty-two-year-old Syrian with ginger hair and impeccable manners, had been at the Camp for a little over a year by the time we met, in December 2017—his asylum denied, his appeal wending its way through the system. Isaac, who asked that I not use his real name, told me he’d been the owner of a pharmacy back in Syria, describing himself as a college-educated, law-abiding churchgoer, details supported by a cache of notarized, translated, verified records. When Isaac first arrived at the Camp, he repeatedly asked himself how he had come to be incarcerated. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) designates the Camp as a “holding and processing facility,” but as far as Isaac could tell, it was a prison. “Like in the movies,” he said flatly.

He would be stuck in the facility, he posited, for who knew how long, having been refused asylum for reasons he couldn’t quite grasp. The judge had initially implied that Isaac, a Christian fleeing both militiamen and Islamic extremists, had a convincing case, but then, in an abrupt about-face, denied him. “Is it personal? No,” Isaac said, perplexed. “Related to the law? Political?” Eventually, he concluded that trying to make sense of his predicament was an exercise in futility. He decided instead to look at his captivity from the US government’s point of view. “In their opinion, I make a crime because I come here with no visa,” he told me. “I convince myself. I say, ‘Okay, I am illegal. I am illegal.’”

In fact, Isaac had not committed a crime. He had not slipped into the country outside a designated port of entry—a misdemeanor or, if done repeatedly, a felony. Instead, in the early afternoon of October 2, 2016, Isaac joined a throng of people in the pedestrian lane of the Paso del Norte Bridge, which divides Mexico’s Ciudad Juárez from El Paso, Texas. Below the bridge ran the physical border between the two nations: a trickle of the Rio Grande, no deeper than a puddle, clogged with trash. When he reached the front of the line, he used broken English to inform a border agent that he was a Syrian national in need of protection. In doing so, he had behaved in accordance with both international human-rights law and US immigration law. He had also crossed into the El Paso jurisdiction, which, though he didn’t know it at the time, was one of the worst places in America to seek asylum.

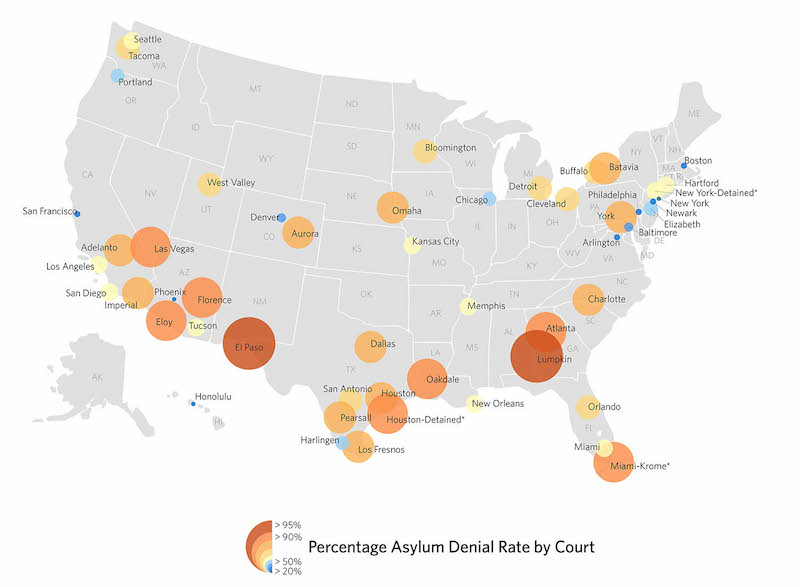

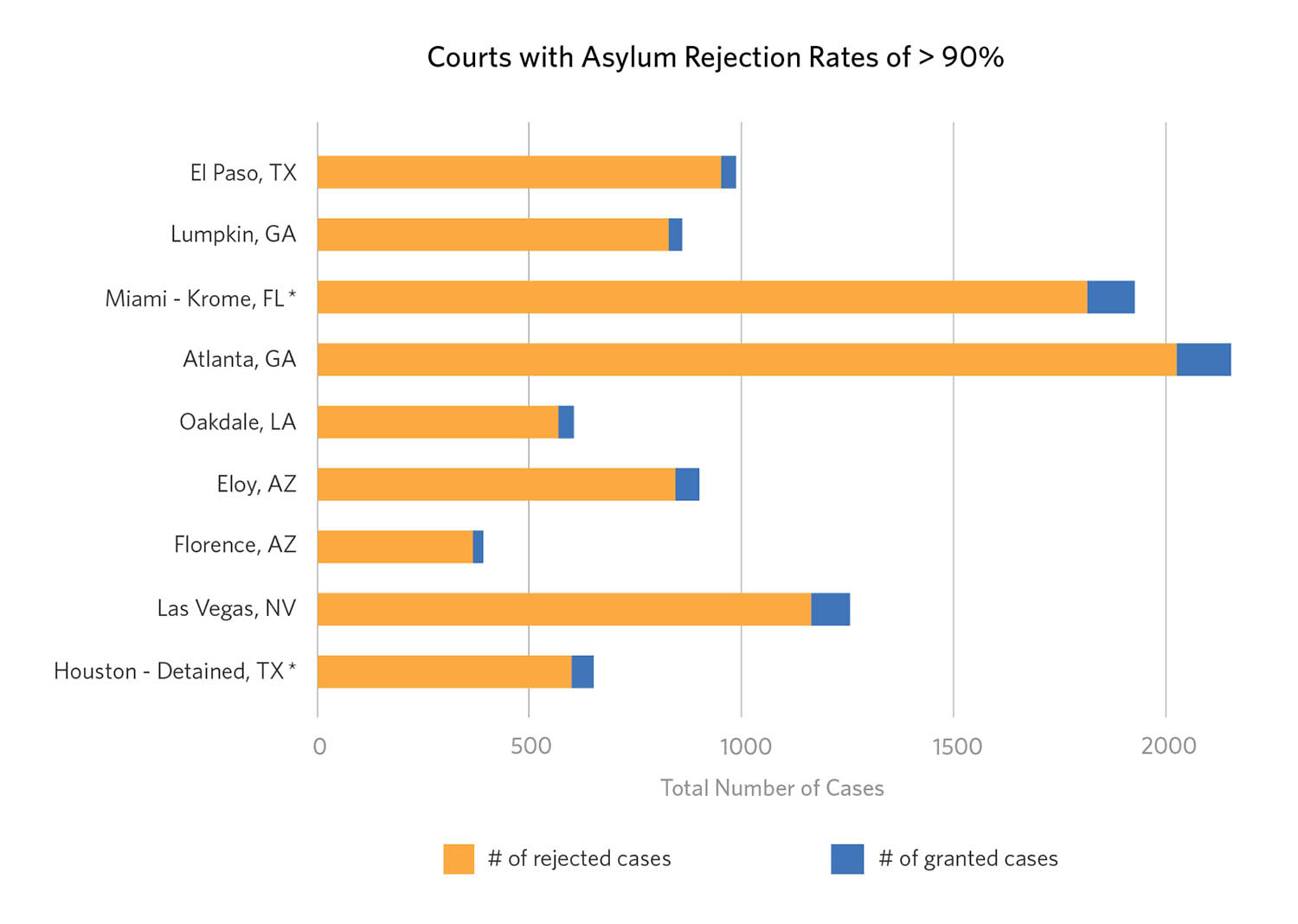

Immigration courts are administrative bodies, divided into regional districts that have developed starkly different patterns of adjudication. Between 2012 and 2017, for example, the New York City court approved close to 80 percent of applications for asylum, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University, which analyzes government data on immigration. In Miami, the approval rate was 30 percent. In El Paso, judges approved asylum seekers at an average rate of just over 3 percent.

This gross imbalance was the focus of a 2007 study, Refugee Roulette: Disparities in Asylum Adjudication, which demonstrates, with disquieting statistics, how rulings vary across the US—not only among jurisdictions, but within them as well—even when controlling for multiple aspects. (In one courthouse, for example, one judge was 1,820 percent more likely to grant relief than his colleague.) But while these disparities point to a dysfunctional adjudication apparatus, a place like El Paso, where all the judges deny nearly all asylum cases, presents a uniquely troubling phenomenon. In a 2016 submission to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, a small group of lawyers shed light on the development of jurisdictions where judges’ rulings are almost all rejections. They call these jurisdictions “asylum-free zones.” Since the hearing venue for an asylum case is most often the court located where the respondent lives or is being held, the authors of the submission suggest that the existence of these zones is tantamount to a sweeping denial of immigrants’ human rights, based on little more than an accident of geography.

Local immigration activists and lawyers contend that asylum seekers in El Paso face remarkably bleak circumstances, including limited access to legal help, a lack of translators for non-Spanish speakers, and inhumane conditions at Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and ICE holding facilities. Compounding this troubling pattern is the sheer volume of cases at hand: Between 2000 and 2018, El Paso had the third-highest number of detainees in immigration proceedings in the nation.

And yet, if he has successfully braved these challenges, the asylum seeker in El Paso—simply by virtue of being there—finds himself before a judge who will almost always deny him, trapped in a jurisdiction that systematically and consistently refuses relief, and has done so for years.

As Carlos Spector, an immigration lawyer who has practiced in the city for thirty years, put it: “As an asylum seeker, you descend into hell by coming here.”

At the Camp, the thermostat always hovers around 69 degrees. Speaking through a static-plagued phone on the other side of a thick pane of glass, Isaac recalled how, at the beginning of his internment, he felt perpetually cold, but that after six months or so he simply got used to it. Sitting in the concrete booth, he wore a frayed, ICE-issued jumpsuit but was immaculately groomed—his close-cropped hair combed and gelled, his beard trimmed—and unerringly pleasant, speaking in English that was once rudimentary but had become nearly fluent during his time in Texas.

Mass trial of immigrants at the Lucius D. Bunton Federal Courthouse in Pecos, Texas.Image: Wikimedia Commons

Isaac shared a dorm with sixty other detainees. His bed was a lower bunk with a revolving cast in the upper bunk—sometimes a new person every few days, sometimes a man who came at 2 a.m. and left at 6 a.m., on the way to a plane or bus that would deport him. Initially, the prospect of strangers rotating in and out of his cell kept Isaac awake, but soon enough he barely stirred when a newcomer climbed past his head to the bunk above.

Isaac’s days took on a dreary rhythm: his shift in the laundry room at six, breakfast at seven, lunch at ten, dinner at five. The food was always the same, doled out in limited portions: oatmeal, eggs, mystery-meat macaroni, Jell-O, milk, ham sandwich, potato chips. Watermelon once a week. Burgers twice a month.

For the first few months, Isaac counted every minute, every hour, compulsively comparing the time: When he woke at 5 a.m. in America, it was 2 p.m. in Syria; when he ate at 10 a.m. in America, it was 7 p.m. in Syria. He called his brother in California every day, at 50 cents a minute, on a phone line contracted out to a private company that monitored communications. His brother dialed their parents, with Isaac on speaker. After a while, Isaac stopped calling much. His brother’s voice and his mother’s tears, he said, pulled him beyond the walls of the Camp. It wasn’t so bad inside, he explained, as long as he didn’t think about his family, his friends, his country, his career, the past, the future, food, drink, sports, music, movies, politics, books, newspapers, technology, cars, women, or freedom. “I try to adapt,” he told me. “I have my life here and I have to live. I can’t compare my life before and my life now.”

Isaac grew up thirty miles northwest of Homs, in Kafr Ram, a lush mountain hamlet nestled in “the valley of the Christians,” home to one of the world’s ancient populations. Before the civil war that broke out in 2011, Syrian Christians were an educated, elite minority. Isaac’s father, now retired, was once a history professor; his mother, an elementary-school principal. His three older siblings are all doctors. Isaac, the youngest, received a degree in pharmaceutical chemistry at a private university near Damascus. After graduation, he moved to Homs and opened his own pharmacy. “It looked like an easy life,” he said. “Quiet. Very beautiful.”

Isaac painted the pharmacy name in red and blue on the window. He imagined that he would own the business for the rest of his life, and endeavored to become a part of the community, administering vaccines free of charge to kids whose parents couldn’t afford to pay. He installed a flatscreen TV and played Arabic music videos, Formula One racing, and American basketball. The Los Angeles Lakers enjoy a loyal fan base in Syria; Isaac, however, is a die-hard devotee of the San Antonio Spurs, a team that he—despite holding nearly encyclopedic knowledge of its coaches and players—long believed represented “the American state of San Antonio.” He didn’t realize the team he’d been cheering on came from Texas, a place he knew of only from Spaghetti Westerns dubbed into Arabic, a place it never occurred to him that he would visit, much less spend hundreds of days in, locked up. It was indeed a stroke of extreme bad luck that Isaac stepped into Texas at all. But then again, the years that preceded his detention had changed his life in a way, he said, that was simply “impossible.”

In 2011, as the Arab Spring rippled across the Middle East, Homs came to be known as the “capital of the Syrian revolution,” a city where thousands of Sunni Muslims, the majority of the population, were pitted against Bashar al-Assad’s pro-government forces. An Islamic extremist element emerged within the initially anti-sectarian opposition, and jihadists soon took control of Isaac’s neighborhood. Men with similar leanings were suspected of kidnapping hundreds of Christians in a northeastern province, selling Christian girls into slavery, and disappearing clerics. Over the years, Christian villages were cleared, and churches and community centers obliterated.

Soon after the uprising began, Isaac sensed a shift in public sentiment toward Christians. For the first time—at the mall, or the supermarket—he could sense Muslims regarding him in a way that was “cold and disapproving.” Female friends and relatives were being urged to wear hijabs. A Muslim friend of many years told him that Syria was now a Muslim country and suggested he leave for Europe. By 2013, Isaac noticed “strange people with long beards standing on the street corner, watching.” These men, he came to understand, were members of the al-Nusra front, a former al-Qaeda affiliate that rivals the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) in its desire to establish an Islamic caliphate by violence. In 2015, he said, these same men began to extort him, charging him a monthly levy to live in his own apartment. He paid, but they still broke into his home, beat him, and destroyed his belongings. Later, they fired on his car and apartment building, which was known to house Christians. During the attack, the men killed Isaac’s Christian neighbor, mutilating the body as the man’s wife and children were forced to watch. The wife used Isaac’s phone to call her relatives for help—there were no authorities to protect her.

“I had a major feeling I would be their next sacrifice,” Isaac would tell the judge during his asylum hearing.

- Too many Haitians, the agents told Isaac. Take a number and come back in two months.

Isaac went to live with his sister, in Kafr Ram, but returned every day to open the pharmacy, which was in an area controlled by a government militia loyal to Assad. Members of the militia warned him to leave; Christians, they claimed, had not defended the country against either opposition forces or the Islamic extremists, and therefore had no right to operate businesses. Soon after threatening Isaac, the militiamen killed a relative of his who had been delivering supplies to the pharmacy, leaving his body on the side of the road and stealing the company car. When Isaac heard of the attack, he hid out in Kafr Ram for a month.

Eventually, Isaac returned to Homs to check on his pharmacy. Alerted to his presence, militiamen surrounded the shop and opened fire. Isaac fled out the back to his landlord’s house, where he hid for several hours before escaping back to Kafr Ram.

“Before that, I cannot imagine the Syrian people like this, with guns, threatening,” he told me. “But something changed inside them.”

Soon, Isaac’s sister began to receive threats for harboring him. There was nowhere left to go in Syria, so he began to look for a way out. A friend who had relocated to Belarus helped Isaac get a student visa to study in Minsk, and Isaac flew north. In Minsk, as per his visa conditions, he took Russian-language classes at a university. But when the semester ended, he was required to pay $3,000 to re-enroll. Isaac didn’t have the money or speak the language. He knew only one person in Minsk, and couldn’t tolerate the brutal winters there. So he decided to move on.

Isaac traveled to Lebanon, where a distant acquaintance sponsored him for a visa. Soon, however, the acquaintance began to extort him by threatening to withdraw her sponsorship unless he paid her ever-increasing sums of money. Meanwhile, Isaac couldn’t find a job, not even as a waiter or a shop assistant. Isaac called his brother, a naturalized US citizen who lived in California, and the two of them agreed to meet in Mexico, where the brother’s wife had relatives. Isaac needed a tourist visa to visit Mexico, but couldn’t get one without proof of a job back in Lebanon. As a favor, a sympathetic Syrian Christian who worked at a shop in Beirut provided him with doctored papers, with which Isaac managed to secure his visa. His brother then bought him a discount plane ticket. Forty-two hours and four countries later, Isaac landed in Guadalajara, Mexico.

After a warm reunion, the brothers discussed Isaac’s bind. In addition to fleeing jihadists and the pro-Assad militia, Isaac had fled military conscription. For well over a decade, he had been exempted from service. But by 2016, Assad was desperate for soldiers. His armed forces, which had once numbered 220,000, had been drastically reduced by casualties, desertions, and defections. Had it not been wartime, Isaac would probably never have had to serve, but his exemptions ran out, and he did not report for duty—an offense punishable by incarceration, torture, and even execution. In Guadalajara, Isaac and his brother went over Isaac’s meager options. Eventually, his brother encouraged him to come to America, believing that he would qualify for protection.

After they parted ways, Isaac took a bus to the Tijuana–San Diego border, only to find it closed. Too many Haitians, the agents told Isaac. Take a number and come back in two months. Instead, he headed east to another official port of entry: Juárez–El Paso.

Modern refugee law was codified by the United Nations after World War II, when countries grappled with the fact that they had turned away Jews and other vulnerable people fleeing persecution and death. The law’s core principle is that of non-refoulement: the practice of not returning a refugee to a home country in which he has been harmed or has a well-founded fear of future harm. A refugee, according to the 1951 UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, is “an individual who is outside his or her country of nationality or habitual residence who is unable or unwilling to return due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on his or her race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.” Technically, Isaac wouldn’t be a refugee if he had simply fled beatings, shootings, and death threats. He needed to prove that he had fled beatings, shootings, and death threats because he was Christian. To be granted asylum, one must demonstrate the existence of “nexus”—the point at which a person’s identity (as embodied in the five categories) and the reason for his terror meet.

“Yes, you were shot and killed and raped, but not because of your political opinion,” Spector told me with exasperation. “Horrible things happen and the judge’s biggest problem is nexus.”

Indeed, nexus eludes many contemporary immigrants seeking relief, such as those fleeing landscapes decimated by climate change or countries wracked with poverty, corruption, starvation, or widespread gender-based violence. Even those who have been targeted by Mexican and Central American cartels and gangs—a major influx, especially in recent years—often find themselves ineligible for legal forms of protection. Simply being born in a violent country—even facing real threats of harm—doesn’t qualify. Few Mexicans and Central Americans can demonstrate a claim of persecution that is due to race or nationality or religion. Few, too, can meet the burden of proving that their persecution is due to political opinion or membership in a particular social group, since such a group must be socially distinct and fundamental to a respondent’s identity. Being, say, a Honduran who is harmed because he refuses to join a gang is not enough. So most Mexicans and Central Americans coming to the US to escape gangs and drug cartels may be unlucky, even fatally so, but unless they’re being harmed on one of the five grounds, they have few avenues for relief.

- “The real agenda was never due process, but to remove as many migrants as possible, as quickly as possible, with little attention to fundamental fairness.”

Asylum offers an immigrant protection and significant benefits: asylum for spouses and children, permanent residency and eventual citizenship, social services, and travel documents. When applying for asylum, an immigrant also often applies simultaneously for two other types of fear-based relief—Withholding of Removal and protection under the Convention Against Torture—that involve more onerous burdens of proof, are hardly ever granted, and do not offer all of the advantages of asylum, though they do offer the potential for work authorization. Still, many people who will likely be harmed once deported do not qualify for any of these forms of relief, and a judge can—and sometimes must—deny them protection.

From the point of view of those who must face down these cumbersome and complex regulations—both judges and lawyers—this legal impasse can be at once understandable and agonizing. “Nobody was holding my family in the basement forcing me to take the job,” Andrew R. Arthur, Resident Fellow in Law and Policy for the Center for Immigration Studies and a retired immigration judge, told me. “If I didn’t do it, someone else would take the $175,000 a year. If Congress wants to change the law to say anyone in danger can stay, they can do that. Until then, you are faced with a mother, a child, an individual who is going back to a bad situation for which there is no relief under US law, and you send them back because that is what the law requires. If you don’t, you are no longer applying the law—you are the law.”

What an asylum seeker’s fate comes down to, then, is often, as in the legal process writ large, an individual human being’s judgment. Yet while immigration judges can skew skeptical or sympathetic and are free to exercise discretion in applying the law, they are nonetheless bound by statute and precedent. Keeping those in mind, they are tasked with assessing the facts and determining the credibility of a case that usually hinges on one person’s purported experience. Respondents can rarely produce eyewitnesses or police or newspaper reports from a foreign country. Many cases, then, boil down to a few questions: Can the respondent, who has an obvious interest in receiving asylum, make a compelling, believable case? Can he secure a lawyer to assist him? And is the judge motivated to find a way to deny him? The respondent must prove that his fear of return is based upon one of the five enumerated grounds, and that there is at least a 10 percent chance of his being harmed—though, realistically, the percentage future chance of persecution is extremely difficult to calculate.

“Do you go into the case deciding you want to believe or not believe?” Paul Wickham Schmidt, a retired immigration judge, told me. Schmidt served for six years as head of the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), the national body of judges that decides immigration-related appeals and sets precedent for the immigration courts. “You can probably think of a reason to deny almost any case, no matter how strong, or to grant almost any case, no matter how weak.”

As in other administrative courts, there is no jury in immigration court; the judge is the sole finder of fact and decider. The judge, then, has an enormous amount of power but does not have a great deal of independence. That’s because immigration judges are not members of the independent judiciary branch, and do not practice in independent courts. Instead, these judges are executive-branch appointees, employed by the Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR), which is housed in the Department of Justice (DOJ). An immigration judge, technically classified as a DOJ attorney, is paradoxically expected to both act in a judicial capacity and follow the orders of her superiors—and a judge has many superiors, a chain of command that includes the Office of the Chief Immigration Judge, who reports to the Office of the Deputy Director of EOIR, who reports to the Deputy Attorney General, who in turn answers to the Attorney General.

Currently, that office is held by Jeff Sessions, the former Alabama senator who has called the Immigration Act of 1924, which drastically limited the numbers of Italians, Jews, Africans, and Middle Easterners permitted to enter the United States (while banning Asians entirely) “good for America.” Sessions has, among other things, spoken of “dirty immigration lawyers,” called his opponents “radicalized” and “open borders advocates,” threatened to defund sanctuary cities, supported the end to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), overturned a landmark case protecting immigrant survivors of domestic violence, and ordered a “zero tolerance” attitude toward families crossing the border, the result of which was the mass separation of children from their parents, which Sessions defended as righteous by quoting scripture. “This is a new era,” he has said of current immigration policy. “This is the Trump era.”

A Honduran child and her mother, fleeing poverty and violence in their home country, wait along the border bridge after being denied entry from Mexico into the U.S. on June 25, 2018 in Brownsville, Texas.Image: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Sessions is also ultimately in charge of appointing new immigration judges, the recruitment standards for whom are already murky. “There’s no test, no merits-based appointment system,” Andrew Schoenholtz, a professor at Georgetown Law, told me of the hiring mechanism. “That doesn’t mean there aren’t good judges. It means it’s hit or miss.”

Schoenholtz has long recommended allowing immigration judges independence, either by creating a special court or an independent adjudicatory agency, especially because judges deal with asylum seekers. Refugees are among the most vulnerable people on Earth, and the erroneous deportation of an individual with a meritorious case can result in that person’s rape, torture, or death. Should the fate of such a person be decided by a DOJ employee working beneath an attorney general with a political agenda?

“The counterargument would be that immigration is a political matter,” Schoenholtz explained. “It’s different from every other area of US law because the government wants to have control over who stays and who is forced to leave.”

Schoenholtz is a coauthor of Refugee Roulette, the 2007 study that exposed the arbitrary factors at work in the outcomes of asylum cases. In the decade since its publication, the US Government Accountability Office has delivered two reports that confirm significant disparities in adjudication, and suggests that judges with rates that diverge too much from the national average be helped to improve their performance. (Though the average changes annually, TRAC shows that for the last decade, it has hovered around 50 percent.) Despite some feeble corrective steps—the expansion of training for new judges in 2008 and the publication, in 2010, of a handbook—little has changed in terms of outcome. According to a TRAC report on asylum disparities from 2010 to 2016, in a single San Francisco court, one judge denied just over 15 percent of cases, while another denied nearly 98 percent of cases. And in Newark that year, one judge denied nearly 16 percent, while another denied nearly 99 percent.

The lack of any serious overhaul of a clearly flawed system is largely due to a lack of motivation and dearth of resources. “Congress is responsible for the immigration-adjudication system, and when there is political will to do so, they will reform it,” said Schoenholtz. “Immigrants in removal proceedings don’t vote, and they’re not citizens. The interest groups that Congress responds to are not there in this case—for the moment.”

In the meantime, judges are working within a defective system that is also being crushed by an unprecedented number of cases. The DOJ has implemented various policies aimed at hastening case dispositions, which, according to a TRAC report, have had the opposite of their intended effect, pushing the backlog to an all-time high. Recently, the Trump administration decided that, with just over 350 judges facing more than 740,000 accumulated cases, judges will now be evaluated on the basis of “numeric performance standards.” Beginning this fall, they will be required to complete 700 cases annually, including complex asylum claims, to earn a “satisfactory” grade. Sessions argued that quotas would ensure “the efficient and timely completion of cases and motions.” But immigration lawyers and judges have expressed concern that a quota system will put undue pressure on already overwhelmed judges and further threaten the rights of immigrants to due process.

“The real agenda was never due process, but to remove as many migrants as possible, as quickly as possible, with little attention to fundamental fairness,” Schmidt said.

Since its first iteration in 1983, the immigration-court system has been subjected to the ebbs and flows of partisan politics. Janet Reno expanded the BIA to include judges of diverse backgrounds—former government attorneys as well as academics, NGO lawyers, and immigrant defense practitioners. Attorneys general under George W. Bush subsequently removed most of the moderate and progressive board members and tried to appoint only those with Republican leanings. The Obama administration employed a method that Schmidt calls “strategic negligence,” largely by maintaining the status quo, which was one without mandatory representation for immigrants, who often went before judges with prosecutorial backgrounds and wide latitude.

Under the Trump administration, the concept of due process for immigrants and asylum seekers appears to have been subjugated by a nativist ideology at odds with the American ideal of an open, egalitarian, multicultural society (in February, the federal agency that issues green cards and grants citizenship to foreign-born people changed its mission statement from a pledge to fulfill “America’s promise as a nation of immigrants” to a vow to adjudicate immigration requests while “securing the homeland”). In June, following an uproar related to the administration’s policy of separating families at the border, Trump tweeted his thoughts: “We cannot allow all of these people to invade our Country. When somebody comes in, we must immediately, with no Judges or Court Cases, bring them back from where they came.”

When I spoke about El Paso’s asylum-denial rates to A. Ashley Tabaddor, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges (NAIJ), she argued that a jurisdiction’s disparate rates aren’t necessarily troublesome. “Generally, the statistics or the numbers being used are premised on the theory that judges are being randomly assigned cases, and that is misleading,” she said. “Judges aren’t being given an equal amount of the same type of cases, so the premise is faulty. You’re comparing apples to bicycles.”

Still, I asked Tabaddor, doesn’t a consistent denial rate hovering around 97 percent seem problematic?

“I understand the emotional appeal and the desire to fit it into a picture, but it really is about that individual person and that individual case,” Tabaddor said. “We can’t look at macro indicators because they don’t tell the whole story.”

Even without the intimate details of numerous individual cases, we can still examine a region statistically, and those statistics can make a convincing case that a jurisdiction is a sharp national outlier in how it handles asylum claims. To put that pattern in perspective, I enlisted the help of Thania Sanchez, a Yale University assistant professor of political science who focuses on international law and human rights. Together we analyzed a data set, released by the government in response to a Freedom of Information Act request, that covers more than 4 million asylum cases over sixty-four years, from 1950 to 2014.

As Tabaddor noted, each asylum case is unique, and each jurisdiction must contend with its own particular variables; examining decisions out of context can lead to a distorted view of a judge’s leniency or harshness. Asylum is a discretionary form of relief; judges, being human, are subjective, and must contend with factors that may be distinct to their regions and their dockets. Some judges, for example, are assigned to incarcerated immigrants with criminal convictions, while others see nondetained asylum seekers with clean records. Some judges practice in jurisdictions with ample pro bono legal services, where most asylum seekers have lawyers, while others see immigrants who are largely unrepresented. (The NAIJ lobbies for increased representation of immigrants, which it says makes the process more fair and expedient.) Each court also receives its own pool of respondents. Due to its geography, a border court such as El Paso is more likely to receive Mexicans and Central Americans from the Northern Triangle (a region comprising Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) fleeing gang or cartel violence, claims that are difficult but not impossible to win because of the narrow criteria built into asylum law.

Disentangling what is really happening in one jurisdiction requires interrogating the data from multiple vantage points. First, Sanchez and I dug into the effects of having a lawyer. Our findings were stark. Nationally, those represented by a lawyer had a 40 percent chance of winning asylum, while those without a lawyer had a dismal success rate of 6.4 percent. In El Paso, legal representation had a much smaller impact. There, those with legal representation raised that rate to just 19 percent, while those without had a 3.9 percent chance of success. Even though having representation in El Paso helped when compared to not having any, it didn’t help when compared to the national average. Having a lawyer in El Paso gave you close to the same chance of winning asylum as someone without a lawyer in San Francisco.

The Investigative Fund analysis of Syracuse University Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse based on Department of Justice data, FY2012–2017.

Perhaps El Paso’s rates had to do with the disproportionate number of respondents who came from the Northern Triangle or Mexico—a population that fares worse in immigration courts nationally than other potential refugees—who have only a 32 percent success rate for those who can find representation, and only 3.7 percent for those without. Their odds were even worse in El Paso, where respondents from Mexico or the Northern Triangle had only a 19.4 percent success rate with an attorney, and a 3.6 success rate without. The result is that on average, once the numbers are weighted, all asylum seekers from Mexico or the Northern Triangle—both represented and not represented—had a 7.8 percent success rate in El Paso, compared with a 32.7 percent success rate about a thousand miles away in San Francisco. And asylum seekers from elsewhere in the world experienced the same disparity: 11.2 percent received asylum in El Paso, while 48.9 percent received asylum in San Francisco.

El Paso, we discovered, is also particularly bad for people like Isaac, who have secured legal representation and have the advantage of not coming from Mexico or the Northern Triangle. Elsewhere in the country, his odds of being granted asylum, on average, were 46 percent. But in El Paso, we found his chances of success were just over 18 percent.

As Tabaddor noted, it’s impossible to investigate each case to see if it indeed has merit. But looking at the numbers, there is no immediately plausible way to defend the extremity of El Paso’s denial rates. Something other than representation or nationality is at work.

“You’re never going to get granular detail on asylum cases, but if you can parse it out, the conclusion is for your audience to draw,” said David Baluarte, associate clinical professor of law at Washington and Lee University School of Law, and the lead author of the submission to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights that coined the phrase “asylum-free zones.” “The question for me comes down to the culture in the court itself and the ability of people to actually present their facts and evidence. Whether you’re represented or not, are you in a courtroom where the judge and the ICE trial counsel have some sense that they have a responsibility and space to elicit that narrative?”

A primer on El Paso’s judges may suggest an answer. Refugee Roulette found that judges’ rulings on asylum cases are influenced by factors such as professional background. A judge who previously worked as a defense attorney at an NGO or who was in academia is more likely to grant asylum than one without such experience, while a judge who previously worked at the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) or at any of the agencies under the Department of Homeland Security, including ICE, is more likely to deny asylum claims than a judge who has no experience in those agencies. Of El Paso’s seven judges, every single one spent years as a prosecutor for the government, most for ICE. According to their official EOIR biographies, none of the judges has represented an immigrant.

“It’s a culture of ‘no,’ on steroids,” Olsi Vrapi, principal at the New Mexico and West Texas law firm of Noble & Vrapi, told me. “You have seven judges who are all naysayers, so if you come in as the eighth judge, you conform.”

When I met with Isaac at the Camp in December 2017, he could remember only two people who had been granted asylum that year, and mentioned friends with whom he worked in the laundry room—men from Iraq, Iran, Armenia, Bangladesh—who had been detained for two or three years.

But Isaac held out hope. He requested a Bible in Arabic. He prayed and he fasted. All things considered, he seemed to have the kind of case that could rise above the grim statistics.

For one, he could prove that he was exactly who he said he was. Judges are tasked with ascertaining valid claims, but also with sussing out imposters. This responsibility produces what Schmidt called “nightmare theory”: “There are two nightmares you can have as a judge,” he said. “One is that someone you deported was executed by a firing squad when he got off the plane. The other is you granted many cases as part of a fraud ring. Which kind is worse to you probably says what kind of judge you’ll be.”

Throughout the years, the US government has exposed various fraud rings run by unscrupulous brokers or attorneys who coach immigrants on how to game the system by providing people with backstories that fit asylum requirements. One man who ran a Brazil-based ring had several clients who were members of Somali terrorist groups, some of whom successfully entered the United States. A Nepali national in Mexico City, who said she helped at least ten people enter the US every month, also worked with her clients to improve their chances at asylum. In a notable case in 2004, the leader of one ring in Virginia pleaded guilty to falsifying documents for nearly 2,000 Indonesians, including asylum seekers who were coached to tell stories of being abused by Muslims on account of their Chinese ethnicity or Christian faith.

- “Abbott is a mastermind of manipulation.”

Determining who is a true refugee can be especially difficult when a person’s identity is hard to verify. Many asylum seekers claim to have lost a passport on the long journey—to robbers, to the jungle, to the sea, the river, the elements. Others come from countries with broken infrastructures, and so their documents, even if legitimate, are hard to validate.

But Isaac arrived from Syria, a country with a relatively developed infrastructure before the war. With the help of his family back home, who mailed materials to support his asylum claim, Isaac could produce a passport, a birth certificate, a personal-identification card, high school and university diplomas, university records, a baptism certificate, a letter from his hometown priest (who called Isaac his “son in spirit” and asked that the reader “extend help to him according to his need”), a business license, and a military-recruitment booklet that exempted him, year after year, until 2016, when he was ordered to report for mandatory service.

Most promising, Isaac fit neatly into the definition of a refugee. Asylum law can skirt issues of morality, even logic, and can ultimately rest on the technical elements of a case. And technically, asylum law was designed for someone just like Isaac—a targeted religious minority from a country in the midst of a civil war. Schmidt, who sat on the Arlington, Virginia, bench for thirteen years, told me that in his experience, it was simple and expedient to grant asylum to a person who so clearly fit the definition of a refugee. “A Syrian Christian would get a ten-minute grant in Arlington,” he said.

Isaac, unlike most of El Paso’s detainees, was able to hire a lawyer—and a good one at that. While Refugee Roulette found that any representation was better than none, asylum seekers with high-caliber representation (in the study, these were respondents represented by students with Georgetown University’s clinical-law program between 2000 and 2004) won 89 percent of the time—an exceptionally high rate.

Isaac’s brother hired Jessica K. Miles to represent him. Miles, a thirty-four-year-old Albuquerque native who heads up the El Paso branch of Noble & Vrapi, graduated cum laude with clinical honors from the University of New Mexico School of Law and won the class prize for her work in social justice. She works directly under Vrapi, who is a national figure in the field and arguably the top immigration lawyer in the jurisdiction. Vrapi, who had previously been one of Miles’s law professors, hired her straight out of school in 2014, having seen in her, he said, “a rare passion and fiery resolve.”

Miles was aware of El Paso’s abysmal rates, which caused its immigration attorneys no shortage of misery. (“We feel like such losers,” she told me, letting out a bitter laugh. “Probably because we’re always losing.”) But she was confident that she could win Isaac’s case. In addition to his verifiable identity, clean record, compelling narrative, and personal appeal, Isaac had been assigned to the docket of William Lee Abbott, El Paso’s senior judge, appointed by Reno in 1995. A former INS attorney, beat cop, and Navy veteran, Abbott’s grant rate was just 5.4 percent between 2012 and 2017, but it was the most generous in the jurisdiction.

Among the dozen or so immigration lawyers I spoke with who work in El Paso, more than a few had some rather florid descriptors for Abbott’s fellow judges in the jurisdiction, who were described, variously, as “rabid,” “cruel,” “brazen,” “outright racist,” “bombastic and vociferous,” “jaundiced,” and even “beady-eyed.” For the most part, Abbott escaped these characterizations, with two lawyers telling me that they noticed that he seemed to try to find ways to provide relief without giving asylum, sometimes bonding out meritorious cases so that the people could move elsewhere—which may have had the effect of keeping his denial rate artificially high. In 2015, the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) successfully sued the DOJ for the release of a comprehensive list of immigration-judge misconduct. Though the names of the judges were supposed to be redacted in the 16,000-page document, they were sometimes accidentally laid bare. In one instance, a lawyer complained that Abbott had made an unspecified “anti-Muslim comment” while deciding the case of a Muslim asylum seeker. (According to the document, Abbott received “oral counseling” from an EOIR representative.)

Abbott also had a unsettling tendency to be friendly to asylum seekers before refusing their claims, which meant that when he issued a denial, as he almost always did, it could feel like a crushing betrayal.

“Abbott is a mastermind of manipulation,” Jesus Rodriguez Mendoza, a Venezuelan asylum seeker, told me on a call from the Camp, soon after Abbott had ruled against him. “Every time I used to see him, he would wink, and he told me off record that he was sympathetic and knew my country’s conditions. But there are two judges: One before the court and one after.”

In one case, Abbott appeared to be sympathetic to sixty-three-year-old Berta Arias, who brought her fifteen-year-old granddaughter to the Paso del Norte Bridge and requested asylum. Back in their native Honduras, Arias claimed, members of MS-13 had tried to entangle the girl in a forced relationship—a formalized arrangement to rape her, in which she would be required, against her will, to “date” a gang member. Arias was told that both she and her granddaughter would be killed if they resisted. Abbott found that Arias didn’t qualify for asylum, but granted her protection under the Convention Against Torture. Three days later, he reopened the case and reversed his decision, denying protection. Abbott relied on an unpublished Fifth Circuit opinion to make this ruling, meaning he chose, but was not required, to rescind Arias’s status.

Like most employees of the DOJ, including sitting immigration judges, Abbott is not permitted to speak to the media, and so could not be interviewed for this article, a policy that may contribute to the opacity of these courts.

“You think Abbott is not a judge, he’s an angel,” Isaac told me. “He give me the impression he’s a good man, the best man. But later, I heard about him.”

In late April 2017, Miles and Isaac appeared in Abbott’s small wood-paneled courtroom inside the Camp. Abbott, a congenial-looking man with graying hair and a bushy mustache, wore his black robes and sat before a DOJ seal, flanked by his clerk and the Arabic interpreter. Isaac, in his jumpsuit, sat at his own table, directly across from the judge. Miles and the ICE prosecutor, a young woman named Claudia Ochoa, faced each other from the sides of the small room. (Ochoa, who is not permitted to discuss the details of specific cases, declined my request for an interview.)

Miles argued that Isaac qualified as a refugee on two grounds: as someone persecuted because of his religion and as a member of a particular social group, which she classified as “Syrian men subject to a conscription order who have fled the country.” In his testimony, Isaac recounted his struggles, responding directly to Abbott’s questioning, sometimes with Miles chiming in, clarifying, correcting. Isaac was collected and deferential, but also firm.

The Investigative Fund analysis of Syracuse University Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse based on Department of Justice data, FY2012–2017.

The prosecutor’s main argument against asylum was that Isaac was possibly lying, because it appeared that he had not been entirely consistent with his story. She supported her claims by presenting to the court the statement Isaac had made at the border, without an interpreter, during his first hours in the US.

The three-page, single-spaced document, recorded by two unnamed CBP agents, tells a variation of Isaac’s narrative. The main facts are not terribly different from the story he would tell for the next year and then some—one that was, at its core, simple: He was attacked for his Christianity; fundamentalists and government soldiers alike targeted him for death; he was extorted, assaulted, threatened; and he fled, to study in Minsk, to find work in Beirut, to meet his brother in Guadalajara and, ultimately, to seek sanctuary in the US.

The prosecutor did not challenge Isaac’s Christianity or his identity, but instead focused on inconsistencies between accounts as to how he had obtained his visa to Mexico. The border agents had written that Isaac had obtained it “fraudulently.” That document also said that Isaac was a Syrian pharmacist persecuted for his beliefs, who had obtained a student visa in Belarus. According to the agent’s understanding, after six months, he had entered Lebanon, where he was given a visa with the help of a “smuggler”; and had asked a “cousin” who worked in a shop to give him fake employment documentation in order to get a travel visa to Mexico.

There were two considerable problems with the border statement, the first of which was that of materiality. Reasonable people understand that those running for their lives are sometimes unable to go through official channels to get proper visas, or must lie to save themselves (asylum is, after all, largely available to people being persecuted by their own governments). Despite all the challenges, Isaac had actually tried to follow legal procedures whenever he could. As to the fake work documentation, Isaac admitted to the prosecutor and anyone who asked that he had never worked in Lebanon. “I had to do it because my life was in danger,” he explained in court.

The second issue with the border statement was its reliability in general. Normally, a government agent, who acts as the interrogator, creates a transcript of his interview with an immigrant—who often does not speak English, and usually does not have access to a lawyer or a translator—and then asks him to sign it. These transcripts raise major questions about the legitimacy of the process. In 2014, AILA illustrated the unreliability of border statements by highlighting a case in which a signed, countersigned, and witnessed document showed that an agent conducted a lengthy interview in which he asked an immigrant why he left his home country.

“To look for work,” the immigrant allegedly answered.

AILA observed that the immigrant who had supposedly submitted to the intensive questioning, signed an affidavit, and admitted his intention to look for a job was, in fact, a three-year-old child.

“The border interview is not a modern practice,” Bradley Jenkins, an attorney at Catholic Legal Immigration Network, told me. “It’s a smoke-filled room. You don’t have counsel. It may or may not be interpreted. It’s rarely recorded, which is best practice with interrogations. It’s a transcript, and as we have occasionally seen, it’s not really a transcript at all. Some officers see what they can get away with putting in there.”

Nonetheless, many judges give these statements serious consideration, casting doubt on an immigrant’s credibility because his story during a brief border interview, or a written application prepared in his nonnative language, is not precisely the same as his eventual testimony in court.

In Isaac’s case, the document presented by the prosecution was more removed than a typical border interview, because it was presented not as a transcript but as a summary of an interview, conducted without an interpreter and then reconstructed by the agent. Miles had requested all prior statements from the prosecution but had never been provided with this document. She felt the color drain from her face when Ochoa introduced it as evidence.

“[The ICE prosecution] is notorious for not giving you documents you have asked for several times, and then bringing them up after the client testified and insinuating the client is hiding stuff,” Miles told me later. “This unverified, regurgitated interview was objectively a garbage document.”

Abbott seemed to largely dismiss the significance of Isaac’s admission that he had lied about having a job in Lebanon to obtain a Mexican tourist visa, and of the three-page document itself. “Don’t have a heart attack yet, okay?” Abbott said to Miles, elaborating that he “might not be able to rely upon it in any way,” because it was “a one-sided agency report which provides information that respondent may have said something slightly different about obtaining documents through maybe misrepresentation at the Mexican consulate in Lebanon.” Miles was shocked that Abbott was entertaining the document at all, but felt nominally relieved by his repeated acknowledgment of its insignificance. “So it has—if any weight, it’s really small,” Abbott said.

It seemed likely, then, that Abbott would actually grant Isaac asylum. “I probably have enough information in the record to make a positive decision if I can be assured that there’s at least a 10 percent chance of harm coming to him if he returns to that country,” he said.

Isaac and Miles left the court feeling optimistic. After the case was finished—the hearing took place on two separate days, nearly a month apart—the attorneys filed their closing statements with Abbott. From then on, every day, at least once, Isaac called a 1-800 number for detainees and listened for an update. For nearly two months, nothing. Then, in early July, the system announced: “Order of removal.” He hung up and called back. “Order of removal.”

Isaac called Miles, who rushed to the downtown courthouse and requested a copy of the decision. She flipped through the first ten pages outlining Abbott’s reasoning until she found her way to the last page:

“Because respondent did not corroborate his testimony with reasonably available corroborative evidence regarding important facets of his testimony, along with making clearly inconsistent statements to various law enforcement entities over time, respondent has failed to meet his burden of proof…. For these reasons, the court will deny his applications for relief in the form of asylum, withholding of removal, and protection under the Convention Against Torture…respondent is ordered removed to SYRIA…”

“It was like two different Abbotts,” Miles said. “Like the Abbott who heard testimony was not the Abbott who issued the decision.” She was overtaken by a fear that Isaac would give up and allow himself to be deported—in which case, she was sure he’d be killed.

Miles drove to the Camp. In the contact room, she sat across the table from Isaac, who was disconcertingly placid. He did not blame her for the defeat. Rather, if there was any way to win, he was confident Miles would eventually find it. If he was destined to be sent back to Syria, it wouldn’t be for her lack of trying.

A child reaches through from the Mexican side of the U.S./Mexico border fence on June 24, 2018 in Sunland Park, New Mexico.Image: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Without consulting Vrapi, Miles offered to handle Isaac’s appeal for free. She didn’t want financial considerations to factor into his decision to try to save his own life. She told him to take a week to decide.

That night, Isaac lay in his bunk and thought about his situation. He loved Syria, at least as it had once been, and he hoped to return someday. Several immigration attorneys told me about detained clients who, despite having cases that might win on appeal and despite facing possible death or torture in their country, buckled when a judge denied their asylum claims. Hopeless, and unable to bear living behind bars indefinitely, they stopped fighting and went home. Indeed, part of Isaac wanted to take the deportation order, just to get out of detention, but he felt that if he were murdered upon his return, his parents would suffer too much. Two days later, he called Miles, thanked her, and said he would stay in the Camp and wait for a decision on the appeal.

Understanding why Isaac’s case was denied may be more alchemy than hard science. A judge does not always base his decision on credibility, but an assessment of credibility plays into most cases to some degree: A judge must believe that the asylum seeker is who he says he is, suffered what he claims to have suffered, and needs the protection he swears he needs. But to deny purely on the basis of credibility, a judge must cite his reasoning, and must be able to point to specific evidence within the record that was misleading or inconsistent—and the misleading or inconsistent evidence must also be relevant to the refugee’s claim. According to the US code, the judge must consider “the totality of the circumstances, and all relevant factors.”

“Credibility is the best way to deny because it’s the most easily reviewable,” said Arthur, the former judge and current fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies. “Generally, credibility determinations are based upon inconsistencies in testimony between witnesses. It is the most easily reviewed because the record will reveal the inconsistencies.”

“Credibility is the scoundrel’s last resort,” argued Spector, the veteran immigration attorney. Human beings can behave irregularly, and even then, it doesn’t mean they’re necessarily untrustworthy. “Two witnesses share a room and one says he saw trees when he woke up and the other says he saw a parking lot. Well, they both had different windows. Where witnesses are testifying, there are going to be inconsistencies.”

A judge may also take into account intangibles, such as a respondent’s demeanor, when assessing his or her credibility. But a person’s demeanor can be affected by any number of factors that may be unfamiliar to the judge charged with evaluating it.

“We get a lot of asylum seekers that speak Spanish, which is very colorful,” Steve Spurgin, an El Paso immigration attorney, told me. “They answer the question by telling a story, and it can appear that they are trying to evade the question, but they are answering in a manner in which they would answer in their culture. A judge will use this as an inconsistency and reason to deny. Asylum laws are stacked against non-English speakers, particularly those who come from Spanish-speaking countries.”

A person’s demeanor can also be shaped by a traumatic experience, the details of which refugees are typically asked to recount in a courtroom. Traumatic memories, which are encoded in the brain differently than regular memories, can be fragmented, lost, shaky. People suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder may have difficulty concentrating or recalling specific events, or may experience amnesia related to their trauma.

“I had a case where they cut my client’s brother into pieces, and the judge found she wasn’t credible,” said Eduardo Beckett, an El Paso immigration attorney. “She was a little crazy, but I was like, ‘If someone cut your brother into pieces, would you be with it?’”

Tabaddor, of the NAIJ, told me that there is, of course, a subjective element to any sort of adjudication. “Someone needs to make the call,” she said. “That’s just law and judging. There is no objective way to determine something. There is no truth serum, no computer, no way to know if someone is a fantastic actor, or they are traumatized. We are not in the ‘gotcha’ business. We are there to make sure both parties have their day in court. Credibility determinations, by their very nature, have to be made by somebody.”

El Paso judges most likely believe that they are interpreting the law fairly, ethically, and judiciously. However, for them to believe that, they must also believe that year after year, almost every single asylum seeker who comes before them has a claim with no merit.

Judge Thomas C. Roepke, for instance, saw 196 asylum seekers in his courtroom between 2009 and 2014, and determined that only two deserved asylum, according to TRAC. Between 2011 and 2016, Judge Guadalupe R. Gonzalez saw 101 asylum cases and granted only three. Judge Sunita B. Mahtabfar decided 159 asylum cases, and granted asylum just once.

Nationality alone cannot explain the rates, as Sanchez and I found. These judges faced a majority of Mexicans and Central Americans, but they also saw noteworthy numbers of Indians, Somalis, Chinese, Bangladeshis—and smaller numbers of Eritreans, Iranians, Iraqis, Ethiopians, Chileans, Cameroonians, Ghanaians.

Precedent rulings from the circuit courts could conceivably figure into the denial rates. A case is first heard in immigration court. If either the respondent or the prosecutor doesn’t like the result, they can appeal to the BIA, a nationwide body. If the respondent—and only the respondent—does not like that result, he can appeal to his circuit court of appeals, one of thirteen federal courts that decide appeals from all the district courts, including immigration courts, within their circuits. Since immigration judges must consider circuit court precedent when ruling, decisions by these appeals courts could affect denial rates circuit by circuit. El Paso judges practice in the conservative Fifth Circuit, which includes all courts in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

According to Sanchez’s analysis, the average asylum grant rate in immigration courts within the Fifth Circuit is 8.9 percent, the lowest in the country (the average grant rate in courts within the Second Circuit, which includes New York, Connecticut, and Vermont, is above 36 percent). Those without representation in the entire Fifth Circuit, including El Paso, have an extremely low chance of success—below 4 percent. For those with representation, the average success rate in all other circuits is nearly 42 percent, but is only 25.6 percent in the Fifth Circuit—which, dismal as it is, is still six points better than El Paso.

Since the rates cannot be adequately justified by nationality, representation, or circuit, one other explanation would be simply that El Paso is stuck with more unworthy claims than other courts in the country. In other words, El Paso courts reject the immigrants who enter the area, year after year, because those immigrants are less eligible for asylum than individuals who enter nearly everywhere else, a scenario so unlikely as to verge on the absurd.

Immigrants find themselves in El Paso in several ways: They either present themselves at the Paso del Norte Bridge, as Isaac did; are apprehended in the jurisdiction when sneaking across the border between checkpoints; are arrested within the jurisdiction during a traffic stop, checkpoint, or raid and are then taken into ICE custody; are taken into ICE custody from a local jail; or are transferred from a facility in another district. Other immigrants are paroled or bonded out elsewhere, and, likely unfamiliar with the jurisdiction’s dreary statistics, they then move, often to be near family, to New Mexico or West Texas; these unlucky individuals are required to have their hearings in an immaculate courtroom in the El Paso city center. For years, most nondetained migrants seeking asylum stood before Roepke, who denied 97.1 percent of claims between 2012 and 2017, which, according to TRAC, made him the fifteenth-harshest judge in the country for asylum seekers. Roepke retired earlier this year, to be replaced by his colleague Gonzalez, who had previously decided detained cases, denying 97.3 percent and earning a spot as the eleventh-harshest judge nationwide. A judge in Oakdale, Louisiana, who denied 100 percent of asylum seekers for four years running, secured the number one spot.

But the detained population moves around, which offers insight into the effects of judges. Some detainees, like Isaac, remain at the Camp. Others are moved to West Texas Detention Facility, in the tiny, impoverished town of Sierra Blanca. Detainees at both of those facilities have their cases heard by the El Paso judges. However, some immigrants are funneled to two other facilities: Otero, a remote, privately operated New Mexico detention center, and Cibola, a former New Mexico state prison, run by the private firm CoreCivic, that was shuttered in 2016 after multiple inmate deaths due to medical negligence. Within three months, the prison was reopened as an ICE detention center, still owned by CoreCivic.

The immigrants who land in Cibola and Otero are largely from the same pool as those who go before El Paso judges. Cibola is located in New Mexico, which is in the Tenth Circuit (the second worst for asylum seekers); these days, their cases are heard via videoconference by judges in Denver, also a court in the Tenth Circuit. Otero is also located in New Mexico, but until 2017 its cases were funneled to El Paso, and its asylum statistics were lumped into El Paso’s.

- “They hire over and over only people from the prosecution.”

In spring 2017, Sessions announced that in order to deal with the growing backlog on the border, he would send a “surge” of judges from across the country to sit at border courts, including Otero, for brief assignments (many of these visiting judges claimed that, despite leaving behind heavy dockets in their home states, there was actually very little to do when they arrived at the border). At that time, the Denver judges began to hear the first asylum cases out of Cibola.

So what were the grant and denial rates for asylum seekers held at Otero and Cibola during that time? If El Paso cases were uniquely without merit, and if the system makes claims of uniformity, the denial rates would likely be extreme. And while the detainees at the Camp are held within El Paso city limits, detainees at Otero and Cibola are geographically isolated, so their access to lawyers is greatly impeded, which could negatively affect the outcome of their cases.

I requested and received 2017 government data on asylum cases for these two courts in order to check. The number of cases is too small to be statistically significant, but they provide some insight into how these judges’ decisions diverge from those of the regular El Paso judges.

Forty-six cases at Cibola were heard by four Denver judges. Of these, twenty-three were denied and seventeen were granted (four cases were withdrawn, and the outcomes of two were not specified). Though all six Mexican respondents were refused, four out of the six respondents from the Northern Triangle were granted asylum. Transgender detainees are transferred to Cibola from across the US, giving the facility a higher trans population than other ICE detention centers (the particulars of each asylum case are confidential and not listed in government data), and the cases were heard in the Tenth Circuit. Still, the denial rate was some forty-seven points below the regular El Paso rate.

At Otero in 2017, visiting judges from across the country made 277 decisions, granting thirty-nine applicants and denying 193 (forty-three others decided not to complete the process and the outcomes of two were not specified). Unlike Cibola with its transgender population, Otero’s immigrant pool is basically the same as El Paso’s. But Otero’s asylum-denial rate was, nonetheless, twenty-seven points lower.

Attorneys accustomed to practicing in El Paso told me that their experiences in front of the visiting judges at Otero and the Denver judges at Cibola were vastly different from their usual experiences at El Paso. “It was heaven sent,” Cynthia R. López, an attorney, told me. “They would give us bond. They would really look at the cases.”

Lawyers also recounted rare instances where cases that had been denied in El Paso were, for a variety of reasons, granted a change of venue. When an asylum seeker was able to appeal a case that had been refused in El Paso in another jurisdiction, his odds of winning improved. One man who was nearly deported in El Paso managed, through a great deal of legal maneuvering, to get his case moved to Denver, where he was granted relief. Two brothers from the Northern Triangle had the exact same case. One brother, stuck in the Camp in El Paso, was denied and then lost both his appeal to the BIA and his Fifth Circuit appeal; the other brother was granted protection in New York. One woman moved to Los Angeles, where her asylum case, which she lost in El Paso, was quickly granted on appeal, to her lawyer’s astonishment.

Much like the data, Isaac’s loss suggested a larger, mysterious problem with the El Paso system. Even if the judges’ near-perfect denial records could be explained away, case by case, with the usual rationales—that the asylum seeker’s identity wasn’t verifiable, that he was fleeing gangs, that he didn’t have representation, that he didn’t fit the definition of a refugee—Isaac avoided all of these pitfalls. During the hearing, Abbott himself admitted it was a good case. And still, Isaac remained at the Camp.

Isaac’s plight couldn’t be pinned to particular facts or factors in his case. Rather, he was living the effects of a culture, which developed over time and which pervades asylum-free zones like El Paso. In these areas, systemically low grant rates seem to stem less from the characteristics specific to each case and more from a damaged ecosystem. In El Paso’s case, deterrent CBP and ICE practices, combined with high rates of denial in a court staffed entirely by former prosecutors, most of whom had previously worked for ICE, appear to have created a self-perpetuating cycle.

“Some attorneys develop bad habits in response to the adjudication of these judges,” Ian Philabaum told me. Philabaum is program director at Innovation Law Lab, which is setting up projects to help asylum seekers in asylum-free zones, including El Paso. “So if you believe this judge is not going to grant a Central American asylum case, you stop taking asylum cases from Central Americans. And then people give up looking for a lawyer.”

“In most courts, people talk,” said Schmidt, the retired judge and former BIA head. “Judges have an idea of what cases their colleagues are granting and denying. And if you grant cases, you give attorneys ideas of what winning arguments may be.” But if each judge only grants one or two asylum claims a year, there’s no road map for how to win.

The apparent consistency of both ideology and work background of the El Paso judges also likely feeds into this cycle. Refugee Roulette suggests that one way to alleviate disparities between judges would be to have judges on either end of the asylum-denial spectrum simply speak with one another about their approaches to adjudication. “In El Paso, we lack a single dissenting voice,” observed John Benjamin Moore, an immigration attorney. “They hire over and over only people from the prosecution.”

From 1995 to 2002, El Paso, then a smaller jurisdiction, had a judge who had been in private practice and had served as a lawyer with the El Paso Legal Assistance Society: a Mexican American named Bertha Zuniga, who moved to the US at age nine. After seven years in El Paso, Zuniga left for a judgeship in San Antonio. In 2015, she retired from the bench and founded her own practice, representing immigrants. Zuniga would not respond to my requests for an interview, but she spoke to the El Paso Times in February 2017. “I sympathize with people’s hardships and used the law to benefit those that were in need and those that were deserving,” she said of her time as an immigration judge. “I tried to not be harsh in the application of the law because I knew where I came from.”

During her years in El Paso, Zuniga denied between 30.8 and 48.8 percent of asylum cases. Abbott took the bench in El Paso in 2002, as Zuniga was leaving, and at first denied just 43 percent of cases. But over the years, his denial rates rose: to 54.6 percent, then 74.4 percent, then 93.7 percent, and then 94.6 percent, according to TRAC. TRAC does not report on asylum decisions for judges with fewer than seventy-five cases, so there is no public record of what former ICE prosecutor Roepke’s denial rates were during his first three years on the bench, starting in 2005. But between 2008 and 2010, he denied 98.7 percent of asylum applications. Former ICE prosecutor Stephen M. Ruhle joined the court in 2008, with an average denial rate of 96 percent during his first years. Former ICE prosecutor Gonzalez joined in 2010, with a rate of 97 percent; CBP prosecutor Mahtabfar joined in 2013, with a denial rate of over 99 percent. Robert S. Hough, a former ICE prosecutor, was appointed in 2005; Dean S. Tuckman, a New Mexico assistant state attorney, in 2016; Michael S. Pleters, a Department of Homeland Security prosecutor, in 2017; and Nathan L. Herbert, an ICE prosecutor, in 2018, but their rates are not reported by TRAC.

One could argue that the El Paso jurisdiction as a whole perceives itself as existing on the embattled frontlines of an immigration crisis. In April 2017, two weeks before Isaac’s case was heard, and some 300 miles west in Arizona, Sessions made a rousing speech, calling the southwest border “ground zero” in the fight against “criminal aliens and the coyotes and the document-forgers [who] seek to overthrow our system of lawful immigration.” These people, surging into US territory, would, he stated, “turn cities and suburbs into warzones…rape and kill innocent citizens and…profit by smuggling poison and other human beings…. It is here, on this sliver of land, where we first take our stand against this filth.”

Perhaps a culture fixated on purging “filth,” rather than protecting refugees, has become entrenched here. Immigration judges are not immune to the effects of that culture, which in turn could impact their adjudication of refugee cases from other parts of the world, causing a cascade of collateral damage.

“Any mistreatment of a Syrian is just a reflection of the existing structure locally,” Spector told me. “The practices emerged from years of dealing with Mexicans. To recognize the violence in Mexico, our largest neighbor, is to open up the floodgates. So you have to say people are coming to fix their papers, to call them opportunists, traitors, criminals. The Syrian is incidental.”

Though he had decided to appeal, Isaac was resigned to his continued confinement, convinced that the entire immigration apparatus had conspired to place protection out of reach.

In the meantime, Miles spent her nights and weekends researching and writing Isaac’s brief, an exhaustive forty-two-page argument. In October, she sent the finished product to the BIA in Falls Church, Virginia. Miles doubted that Isaac would actually win asylum on appeal, she admitted to me, because she couldn’t pinpoint how he had lost, exactly; since she had been convinced that the original case was airtight, and Isaac had been denied anyway, she wasn’t quite sure how to succeed. But she knew she had to prove, unequivocally, that Abbott had been completely wrong in his adverse-credibility decision—a daunting task. She was compelled to do everything in her power. For her, it assumed the same urgency as fighting a death penalty case for an innocent man. In the formal briefing, she enumerated the ways in which Isaac had presented credible and consistent testimony and evidence, highlighted the flaws of the border statement, and dissected how Abbott had erred, citing dozens of precedential decisions.

In theory, the BIA exists to provide a system of checks and balances, increasing adjudication consistency and reducing the possibility that judges are biased or making unlawful decisions. However, Schmidt said that to call the board fair and adequate would be reductive, and that immigrants and lawyers were right to be dubious of its impartiality.

“The board should have been a place where the views represented spanned the views in the asylum field, but in the end it was a go-along-get-along board,” he said of his time at the helm. Of the BIA’s sixteen current members, all have longstanding careers as government employees. Only two have represented immigrants.

Another reason the BIA doesn’t provide a sufficient system of checks and balances is that many cases simply don’t make it that far. A sweeping analysis of the appeals system found that the mechanism itself is stacked against immigrants. David Hausman, the author of “The Failure of Immigration Appeals,” published in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, found that immigrants who go before judges with high denial rates are no more likely to appeal a denial than those who go before more generous judges, while, conversely, government attorneys who go before judges with low denial rates are more likely to appeal a grant of immigration relief.

- “The board should have been a place where the views represented spanned the views in the asylum field, but in the end it was a go-along-get-along board.”

This largely comes down to issues of time and representation. Simply put: Some judges order immigrants deported quickly, before they’re able to marshal resources, and almost no one appeals without a lawyer. The government, on the other hand, always has a lawyer ready, and can therefore appeal easily. Because of this, Hausman found, there are many worthy cases that the BIA never sees.

Still, Isaac had Miles in his corner, urging him on, and working on the appeal gratis. In large part because of her efforts, he forged ahead.

Just after I left El Paso, I put $25 on a phone account so that Isaac could call me from the Camp, but we never had a chance to use it. The following week, Miles received a slim envelope from the board. She sat on the couch in her office and tore it open.

The Immigration Judge’s adverse credibility finding is clearly erroneous. The Immigration Judge did not question the respondent’s Christianity or nationality. Rather, the credibility finding was based on tangential issues regarding how the respondent obtained his visa.

After more than a year at the Camp and a deportation order to Syria, Isaac had won asylum. He would be released and given lawful permanent residence and a work permit, and would eventually be eligible to apply for American citizenship. Miles sped to the Camp to deliver the news. They met again in the contact room, where they both awkwardly attempted to stifle their tears.

“You’re going home,” Miles said—then quickly clarified what Isaac already understood. “Home to California.”

She knew he was a pious man, from a conservative society, but before she left, she hugged him. “And to this day, I have no idea if that’s acceptable,” she said.

Within the week, once a final security check had cleared, Miles picked up Isaac from the Camp and deposited him at the El Paso Marriott, where his brother had booked him a room. Isaac ordered chicken wings and cake from room service, and watched the Spurs, his favorite team since he was a teenager in Syria, lose to the Rockets. “But it’s okay!” he said brightly, recalling the moment. “No problem.”

The next morning, Isaac’s brother, who had driven through the night from California, collected him. They had a quick Tex-Mex breakfast and called their parents. Isaac had not wanted to speak with them until he had been released, in case of something unexpected—a loophole, a mistake. But he was out now, safely in America.

“Are you sure you’re free?” Isaac’s father asked repeatedly.

“I think so,” Isaac replied, incredulous. “I think so, but I don’t know.”

The brothers headed west, gunning for the state line, since at that point, as Isaac said, “nobody like Texas.” He relaxed a little once they crossed into New Mexico, where trailers and livestock dotted the desert. They passed through Arizona, then entered California, where the highway widened. Once at his brother’s house, Isaac slept and ate for two weeks: fajitas, cheesecake, kebabs. He watched Netflix to improve his English. He and his brother and sister-in-law celebrated Christmas in Las Vegas. For his birthday, in January, he had a small party at a Cuban restaurant in Los Angeles.

He was grateful for this second chance, but also daunted by the idea of starting over, with no car and no license, self-conscious about his English. He worked six days a week, often until closing, in a liquor store at a strip mall. In the mornings, he studied for his pharmacy-assistant exam. He planned to apply for a job as an aide at a drugstore, where he could answer phones and stock shelves and endeavor to learn as much as possible about American medicine. Eventually, he hoped to transfer his Syrian pharmaceutical license to the US and become a pharmacist once again.

In the meantime, his existence remained precarious. Two months into his new life, Isaac accompanied his brother to the airport to pick up his sister-in-law. He was stopped at the airport, and because he did not yet have a state ID, he presented a form, which, he learned, had a clerical error. He was held in the airport for hours until the authorities were satisfied that he had legal status.

“Here in the US, there is democracy, but we still have fear,” he said. “I got asylum but if they want to make a problem, they can do it.” He was terrified that the smallest misstep, no matter how apparently meaningless, how accidental or random, could signal the difference between freedom and imprisonment—and from there, between life and death.

To beat the extreme odds in El Paso, Isaac had spent fifteen months in detention and paid thousands of dollars in legal fees to an elite lawyer who then worked dozens of pro bono hours on his appeal. This feat required an enormous amount of translated and notarized evidence discretely sent overseas by family members in Syria, the emotional and financial support of his brother and his lawyer, and the wherewithal to withstand a complex, taxing, humiliating process. How many asylum seekers could or should have to endure such an ordeal in order to gain internationally recognized rights meant to protect the persecuted?