This is part 3 in a 3-part series. Read part 1 and part 2.

A Manufactured Crisis

Earlier this year, the New York Times ran a front-page story about the outrageous pensions being paid out to a few Oregon retirees. The story, headlined “A $76,000 Monthly Pension: Why States and Cities Are Short on Cash,” featured a former college football coach collecting more than $550,000 a year, and a retired university president pocketing $913,000. The story feeds into a popular myth that retired public-sector workers are getting fat and rich thanks to ordinary taxpayers, who are shouldering the costs of pensions so generous they have triggered a cascade of fiscal crises.

In reality, most retired public workers are living far more modestly. In 2014, the suburban Chicago Daily Herald looked at nine statewide and local pensions, including those enjoyed by teachers, legislators, and university professors. The average pensioner, they found, received $32,000 a year. The Illinois municipal retirement fund pays an average pension of only $22,284 a year, low enough for seniors to qualify for food stamps. Most retired civil servants, moreover, don’t receive Social Security. Despite the rhetoric, public workers are generally paid less than their private-sector counterparts, even when factoring in benefits — 11 to 12 percent less, according to a 2010 analysis of two decades of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Illinois Policy Institute, a conservative think tank with offices in Chicago and Springfield, is one of several organizations that have helped exaggerate the pension crisis myth. Its specialty has been manipulating the numbers to make the state’s pension problems seem even more outsized than they are. Illinois is facing, according to the Chicago Federal Reserve, a substantial unfunded $129 billion pension liability. But Ted Dabrowski, then the group’s vice president for policy, told me, “The state’s really looking at a deficit of $250 billion,” a figure he reached by making the unlikely assumption that the state invested only in low-yield bonds. Yet such research provides the ballast for attacks on pensions by organizations such as the Civic Committee of the Commercial Club of Chicago, a group made up of some of the city’s wealthy, politically active business leaders. The committee uses its influence to push a message that cutting public pensions is critical to Illinois’s well-being.

A Houston couple, John and Laura Arnold, cut a high profile among those interested in public pensions. John Arnold used money he made as an energy trader at Enron to start a hedge fund in 2002. He was worth in the multiple billions by 2010 when he created the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which since its inception has been funding research and campaigns around the United States aimed at sounding the alarm about public pension debt and driving public pension reform. Among the foundation’s biggest gives: $9.7 million to the Pew Charitable Trusts for work on public-sector retirement systems; Pew, in turn, has produced its own headline-generating reports about a rising pension crisis. The Arnolds also personally wrote a $5 million check to a PAC called IllinoisGO, which lists as its purpose giving Democrats who support “difficult, yet responsible choices” political cover from “special interest attacks.” (The foundation also coproduced a report with Pew that raised concerns about pension funds moving into high-fee alternatives.)

Almost no pension system, public or private, is 100 percent funded. But a system doesn’t need full funding, unless every person retired tomorrow. Eighty percent is the threshold the federal government uses when assessing the health of the corporate pension plans it monitors. The credit reporting agencies also employ the 80 percent benchmark as an indicator of financial soundness — if not a lower figure. Fitch Ratings, for instance, “generally considers a funded ratio of 70 percent or above to be adequate.” By those standards, the country’s public pensions are generally doing fine — funded, on average, at 76 percent, according to a survey by the National Conference on Public Employee Retirement Systems. “Seventy-six percent is healthy,” according to Bailey Childers, former executive director of the National Public Pension Coalition, “so long as states keep up their contributions and the investments are managed responsibly.”

- “The anti-pension people love this guy.”

Those who care about carefully assessing the health of the country’s public pensions would need to take into account Wisconsin, South Dakota, and New York, three states where the pension system is over 90 percent funded. They would need to consider Texas, Oregon, Ohio, Florida, or any of a long list of states whose pensions systems are more than 70 percent funded. Except those states don’t fit the narrative being put forward by those seeking to manufacture a crisis to justify wiping out public pensions. That’s why Illinois looms large, along with Kentucky, New Jersey, and a few other states where there’s no denying the systems are in crisis. There first needs to be a crisis to convince people that the problem requires a drastic fix.

Exploiting the Pension Crisis

The governor of Illinois, Bruce Rauner, has been a leading champion of the pensions-in-crisis narrative. Even before he entered the race for governor in 2013, he was outspoken in his belief that the public employee unions were a major reason, if not the top reason, Illinois was in an economic “death spiral.” He was also one of several wealthy corporate executives in Chicago behind a successful effort in 2011 to make it harder for teachers in the state to strike. One of Rauner’s first acts after taking over as governor was to issue an executive order allowing state employees who didn’t want to pay union dues to opt out; he later instructed state agencies to stop collecting the fees on behalf of the unions. That gave rise to the Supreme Court’s Janus ruling, which dealt a crippling blow to public sector unions when it was decided this past June. It was Rauner who preemptively filed suit in an effort to get the case quickly in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. But a judge ruled that he didn’t have standing, so a state worker named Mark Janus became the lead plaintiff in a case Rauner would hail as a “great victory for our democracy, our public employees and the taxpayers.”

Rauner’s most prominent public-sector position prior to his run for governor was as an adviser to Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel. The two had first met in the late 1990s, shortly after Emanuel left the Clinton White House and around the time Emanuel was brought on as a partner at the investment bank Wasserstein Perella & Co. The young politico famously earned $18.5 million during his two-and-one-half years there — much of it courtesy of his business relationship with Rauner. The two did five deals together, including SecurityLink, an alarm company Emanuel brought to Rauner for acquisition. Rauner’s private equity firm GTCR bought the company from SBC Communications for $479 million, then sold it six months later for $1 billion. Shortly after he was elected mayor, Emanuel put Rauner and his wife into what the Chicago Tribune called “unpaid but prominent advisory roles.” Rauner left GTCR in October 2012 and announced that he was running for governor in June 2013.

As soon as Rauner took office, he sought to slash pension benefits, traveling the state to push a plan calling for $2 billion in pension cuts (though he promised to exempt police and firefighters). He stopped only when the Illinois Supreme Court slammed the door on that idea, reminding him that the state constitution included an ironclad provision declaring public pensions an enforceable contractual relationship, “the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.” The justice writing for the 7-0 majority, a Republican appointee, seemed to be talking directly to Rauner when he wrote, “Crisis is not an excuse to abandon the rule of law. It is a summons to defend it.”

Illinois ranks in the bottom third among state spending on core services as a share of state GDP, according to the Chicago-based Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. The state couldn’t afford to shrink the size of government any further, Ralph Martire, the center’s executive director, argues, but the new governor proposed doing just that, with deep cuts not only to pensions, but to public services. For good measure, Rauner used his first State of the State address to propose that public unions be banned from contributing to the campaigns of state legislators and signed an executive order prohibiting public unions from collecting fees from government workers who choose not to join.

Rahm Emanuel's campaign for mayor got under way today without a formal announcement of his bid to replace retiring Mayor Richard Daley.Image: Carlos Javier Ortiz/Washington Post/Getty Images

The American Federation of Teachers keeps what it calls a “watch list”: those managing their members’ money who in turn write big checks to organizations seeking to “reform” the country’s public pensions — which is to say, to eliminate them. Rauner deserved a “special mention” in AFT’s 2018 report for fighting the battle not just from the governor’s mansion, but also with his checkbook. That included the $500,000 Rauner gave, through his family foundation, to the Illinois Policy Institute. (Rauner also employed several staffers from the institute, including one as his chief of staff, until his relationship with the institute unraveled late last year.)

“The anti-pension people love this guy,” said Daniel Montgomery, president of the Illinois Federation of Teachers. The Rauner campaign declined to comment for this article.

Aiding Rauner’s cause has been the scandal that rocked the $51.5 billion Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS. Illinois is home to one of the pension funds that might be called the “overextended”: funds that devote more than 30 percent of their assets to alternatives, the investment world’s catch-all term for private equity, hedge funds, and other complex investments. TRS has an astonishing 38 percent of its holdings in alternative investments — among the highest in the country. At that point, a fund isn’t so much investing as making casino-like desperation bets to try to make up for pension underfunding, as well as for past investment mistakes and bad deals. Those with the highest exposure to high-fee alternatives are also the most vulnerable to pay-to-play. Not surprisingly, TRS has been spectacularly marked by corruption.

Public Pensions Have Been Very, Very Good to Bruce Rauner

While Rauner has fiercely attacked public pensions, public pensions have been very good to Rauner. He owns no less than three homes in the Chicago area: a 6,900-square-foot palace in a tony suburb just north of the city and a pair of units downtown, including a penthouse overlooking Millennium Park that is just a short walk to the private equity firm that has made him so wealthy. There, the fees that for years his private equity business charged public pensions mean that, during Chicago’s brutal winters, he and his wife can choose between the waterfront villa they own in the Florida Keys and a $1.75 million condo at a Utah ski resort. Other options include the sprawling property the couple owns near Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, a pair of ranches in Montana, or the penthouse overlooking New York’s Central Park that they bought for $10 million. When this little-known prince of private equity announced his candidacy for governor in 2013, the Chicago Tribune compared him to an earlier private equity governor who was so rich, it was often viewed as a political liability. Yet whereas Mitt Romney owned six homes, Rauner had nine.

Montgomery, of the teachers union, said that while Rauner and the other two private equity governors in the United States like to “brag about all the money they made for teachers, like they’re do-gooders working in a soup kitchen or something. The part they never tell you about are the multimillion dollars they charge each pension for providing all this help.”

Rauner’s former firm GTCR is one of the thousands of private equity partnerships in the United States that collectively manage hundreds of billions of dollars. GTCR raised a $3.25 billion fund in 2011; another $3.85 billion for its 11th fund, GTCR XI, which closed in 2014; and another $5.25 billion last year for GTCR XII. The general partners, as those who run a private equity firm are called, might throw a bit of their own money, but it’s the “limited partners” who provide the bulk of the cash that firms use to buy up and invest in promising businesses they find.

The universe of limited partners includes foundations, university endowments, wealthy individuals — and pension funds. Rauner once estimated that pensions accounted for half to two-thirds of the money he and his partners had raised.

The pensions truly are limited partners. They write checks but remain passive investors who receive occasional reports about how everything is going and maybe an invite to an annual gathering, where the general partners typically try to wow pension staffers and trustees, some of whom might welcome a free trip to some enviable destination.

There are two primary ways that fund managers get rich off the country’s pensions, a pot that exceeds $10 trillion, including both public and private funds. First are the management fees that any private equity firm, venture capital firm, or hedge fund charges. That’s the money the firm takes off the top to keep the lights on and pay their own salaries, along with those of the analysts and others they have in their employ. According to Crain’s Chicago Business, GTCR takes 1.5 percent, rather than the more customary 2 percent, but that’s still a comfortable amount. At that rate, GTCR would take in $75 million on a single $5 billion fund. Every successful investment ends with the “liquidity event” that lets everyone get paid — a company goes public, say, or sells to a larger enterprise. Typically, the partners take a 20 percent share of that revenue, called “the carry,” before passing along the remaining profits to the limited partners.

How much can “the carry” mean for a firm’s partners? In 1999, Rauner told the Chicago Sun-Times that his firm had generated annual returns of 40 percent over the previous 19 years. After fees, he said, his limited partners averaged an annual return of 30 percent. Anecdotal evidence would suggest that Rauner was exaggerating somewhat. Data from the Washington State Investment Board, a longtime limited partner in Rauner’s firm, published by Fortune in 2011, showed that investors in GTCR’s seventh fund (2000) earned an annual 22 percent over 10 years, while its eighth fund (2003) was providing a return of 27 percent a year. That’s far higher earnings than a safe government bond. But look at the take for the private equity partners: Even a $2 billion fund like GTCR VII earning 22 percent a year would have generated roughly $12 billion in profits over 10 years. GTCR’s cut on such an investment, assuming the standard 20 percent carry, would have been $2.5 billion.

But there’s evidence that private equity firms aren’t satisfied with even those extraordinary profits. The Dodd-Frank financial reform required the Securities and Exchange Commission to more closely monitor private equity firms, which the SEC began doing in 2012. Two years later, the SEC revealed that of the roughly 400 private equity firms the agency had examined, more than half had either charged unjustified fees and expenses, or didn’t have the controls in place to prevent such abuses. Many were inflating the fees they charged, Mary Jo White, then chair of the SEC, told Congress, “using bogus service providers to charge false fees in order to kick back part of the fee to the adviser,” which is to say, themselves. A year later, two giants of private equity were fined for bad behavior. Blackstone paid nearly $39 million to settle an SEC investigation into such unfair practices as failing to disclose that it had negotiated a discounted rate from an outside law firm that continued to charge its limited partners much higher price. KKR paid almost $30 million to settle charges that it unfairly required its limited partners to shoulder the cost of $338 million in “broken deal” expenses — having failed to allocate any of these expenses to the general partners for years.

SEC Chairman Mary Jo White testifies during a House Financial Services Committee hearing on Capitol Hill on November 15, 2016 in Washington, D.C. United States.

A new law in Illinois, passed after former Gov. Rod Blagojevich’s impeachment and imprisonment, imposed strict new campaign contribution limits. An exception was made, however, for the wealthy. If a candidate spends $250,000 or more on their own race, the caps are lifted for everyone in that race. Rauner gave $27.5 million to his own campaign and raised millions more from a coterie of moguls, including fellow Chicagoans Sam Zell and Kenneth Griffin, a hedge fund manager who ranks as Illinois’s richest person. The New York Times’s Nicholas Confessore, who in 2015 investigated the outsized influence of just 158 wealthy families on politics, found that the $13.6 million Griffin and his family contributed to Rauner in 2014 was more than 244 labor unions donated, combined, to his Democratic opponent.

Rauner’s opponents in both the primary and general elections sought to use wealth and his private equity record against him. One ad that aired during the Republican primary featured the death of three women at a pair of nursing homes linked to GTCR — GTCR had co-founded their parent company, and Rauner sat on its board. (The Rauner campaign called the ads “shameful” and noted that the company GTCR had helped found was bankrupt and in receivership by the time of the three deaths.) The Daily Herald discovered that Rauner was claiming tax breaks on three of his homes, though he was entitled to use only one for an exemption. (Rauner paid the back taxes he owed on the extra exemptions.) Other coverage showed that he had falsely claimed residency in Chicago when his daughter sought to attend a well-regarded public high school in the city and then made a $250,000 donation to the school after she was accepted. (“My daughter was highly qualified to go to that school,” Rauner said during the campaign.) The Chicago Tribune found SEC filings showing that GTCR had no less than six investment pools registered in the Cayman Islands, collectively worth hundreds of millions of dollars. “Bruce Rauner makes Mitt Romney look like Gandhi,” a former general counsel for the Illinois Republican Party said that fall.

Rauner won every county in the state outside of Cook County, home to Chicago. His attacks on the state’s public pensions did little to undermine him — in no small part because his opponent, incumbent Pat Quinn, had himself championed a 2013 law that attempted to squeeze cost-of-living increases for retirees. (An orange snake dubbed “Squeezy the Pension Python” represented the pension in one of Quinn’s political ads.) Yet this was still deep-blue Illinois. Though Rauner had said the state should cut a dollar from its $8.25 an hour minimum wage, voters approved an advisory ballot initiative calling on lawmakers to raise it. Though Rauner had campaigned against another initiative calling on Springfield to impose a 3 percent tax on income over $1 million, the millionaire’s tax passed with 60 percent of the vote.

Officials Used Pensions Like a Credit Card

The first time a commission was appointed to investigate Illinois’s pension crisis was in 1913. Apparently, lawmakers failed to learn any lessons. For 78 years running, Tyler Bond of the National Public Pension Coalition pointed out in 2017, the state had failed to meet its full pension obligations. Teachers were given no choice: 9.4 percent of their salary was withheld each year for their pension. Roughly similar proportions were deducted from the pay of other state employees. Yet for nearly eight decades, the state had simply failed to make its mandated contributions to all five of its public pensions.

“Elected officials used the pension system like a credit card,” said Martire of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. That way lawmakers could keep taxes relatively low without cutting services. “They basically said, ‘Somebody down the road is gonna have to pay for this, but by then I’ll be out of office, so I don’t have to worry about it.” The unpaid bill as of earlier this year was $129 billion and counting.

The teachers’ pension, TRS, accounts for roughly $73 billion of those unfunded liabilities, according to TRS’s own analysis.But that underfunding became a true disaster in 2008, after the stock market’s great slide. The fund lost nearly $10 billion in the crash — more than a third of its value at the time. But rather than pursuing a path that stressed plain vanilla investments, the fund’s trustees upped its exposure to high-fee, high-risk investments.

The Illinois State Board of Investment, which oversees investments made by the state employee pension fund, took a similar path. The pension, which covers such public employees as DMV clerks, highway repair crews, and prison guards, more than doubled its exposure to hedge funds between 2007 and 2015, from under 4 percent to 10 percent. The board paid around $331 million in fees to hedge fund managers during that period, according to a study by the Roosevelt Institute and the American Federation of Teachers called “All That Glitters Is Not Gold” — compared to an estimated $37 million the board would have paid to manage the same size portfolio if it had been invested in stocks or bonds. The board’s hedge fund strategy, according to the report, cost the pension some $123 million in lost investment revenue during those years.

A new chair took over in 2015, however, and since that time ISBI has withdrawn its money from 65 hedge funds. Less than 1 percent of its money remains with hedge funds, and just 3.3 percent in private equity, including several million dollars with GTCR that is left over from the tens of millions of dollars it had invested over the years in several GTCR funds. Last year, the pension announced that nearly half of its $18 billion fund was invested in low-cost index funds, saving the fund $50 million in fees over two years, the fund’s chief investment officer said, while also “increasing expected returns.”

Chicago Teachers Union employees and supporters protest outside of City Hall in Chicago, on July 2, 2015. Chicago Public Schools warns 1,400 layoffs may follow after a $634 million pension pay out. Image: NurPhoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Illinois has hundreds of public pensions, more by far than any other state in the country. As of 2016, it had more than 650 locally controlled funds created for firefighters and police not covered by the Illinois Municipal Retirement System — and too small, said James McNamee, founder and president of the Illinois Public Pension Fund Association, to risk getting involved in private equity or other alternatives. A former police officer who served as a trustee of his pension fund in a small Chicago suburb, McNamee created the association in part to help inoculate his peers from high-fee, high-risk investments that he believes are not appropriate for funds under $1 billion. “A lot of what we do is educate trustees,” McNamee said, “because we know there are people out there who want to talk them into things they shouldn’t do.”

Some larger funds in the state have exercised this same caution, such as the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, which Forbes once called the gold standard for other pensions in the state. Its advantage relative to other pensions is that the state collects a fee from participating governments each year, guaranteeing that its funding obligations are met. It has just 3.2 percent of its money invested in private equity and another 6.2 percent dedicated to real estate investments.

Others, such as the State University Employees System, continue to gamble. At $21 billion, SURS is the state’s second-largest pension and accounts for $23.4 billion of the state’s pension shortfall. As of 2017, SURS still had 5 percent of assets in hedge funds, 6 percent in private equity, and 10 percent in real estate. “States that tend to be in more financial difficulty tend to have higher-risk portfolios,” said Bill Bergman, an economist and the director of research at the Chicago-based Truth in Accounting, a nonprofit that pushes for transparency in government financing, told the New York Times in 2017. “In Illinois, the defense is that in the long run, these investments will be good for us. But they’re expensive, opaque, and risky.”

Corruption seemed inevitable with so much money at stake. A former TRS trustee named Stuart Levine, who in 2012 was sentenced to five and a half years in jail, was charged with soliciting kickback payment from investment firms seeking a share of the pension’s assets. An outside counsel to the pension admitted that he helped Levine use the pension’s money to reward major campaign contributors to Blagojevich, who in 2012 was sentenced to 14 years in prison for a range of public corruption charges. Also caught up in the probe was a Chicago lawyer who was previously finance chair for the Democratic National Committee. He confessed that he played intermediary for a Virginia-based investment fund seeking advice on how the backdoor system worked: In exchange for TRS investing $85 million in their firm, he explained, a kickback of $850,000 was customary. To make that happen, the lawyer suggested helpfully, they could enter into a sham consulting contract to disguise the payoff, adding, “This is how things are done in Illinois.” Another federal indictment, handed down in 2009, spelled out how a well-known Springfield power broker used his “longstanding relationships and influence with trustees and staff members” at TRS to steer funds to favored money managers. He would be sentenced to a year in prison and fined $75,000.

Rauner was tied to the scandal through Levine. The two first encountered one another when in 2003, Rauner and his partners were raising GTCR XIII and Levine objected to the TRS board investing $50 million in the fund. The deal was tabled but sailed through a few months later, after Rauner showed up personally at a TRS board meeting. A later corruption probe revealed that CompBenefits, a company partially owned by GTCR, was paying Levine $25,000 a month as a “consultant.” TRS didn’t invest any more money with Rauner’s firm after Levine’s arrest in 2006.

Yet the scandals sparked no great moral shift inside TRS. Barely one year after it had been caught siphoning off fees from its limited partners, the TRS board voted to commit more money to Blackstone, on top of the $165 million it already had invested with the marquee firm. Another behemoth of the private equity world, the Carlyle Group, had been exposed paying a lobbyist millions of dollars starting in 2002 to win TRS business and paid $20 million in fines in 2009 for its involvement in a pay-to-play pension scandal in New York. Yet since 2013, TRS’s trustees have entrusted $255 million in pension dollars to Carlyle. Altogether, over the past 10 years, TRS investments in private equity have more than doubled. Its investments in hedge funds have more than quadrupled.

“It’s a vicious cycle,” said Fred Klonsky, a retired public school teacher who writes an education blog that covers the sorry state of his pension. “The more we’re falling behind, the more and more percentage of the fund that goes into high-risk investments in pursuit of big returns.” So far, it hasn’t proven a disaster. TRS has posted a respectable annual return of 6.6 percent in recent years. But that means TRS is paying exorbitant fees just to reach the national average — 6.6 percent was the average yield Pew found when it compared the performance of the 73 largest state pensions over a 10-year period.

“It’s an age-old debate about whether it’s appropriate for pension to use alternatives or not,” TRS communications director Dave Urbanek said. “Our board is very comfortable with our asset mix, which has been designed to reduce risk in the next downturn in the stock market,” he added, noting that KRS posted an 8.5 percent return in the most recent fiscal year.

Yet the veiled nature of alternative investments still troubles Klonsky. “There’s a level of secrecy, a lack of transparency that I don’t like,” Klonsky said. “There’s basic information that we can’t get. How much in fees are we paying? I look at the trustees and they don’t want to seem to get directly involved in determining the direction of investments. Instead what happens is they hire somebody who brings in consultants, and more and more of our money ends up going into this stuff.”

The Trouble With Private Equity

On the campaign trail in 2014, Rauner liked to describe himself as the grandson of a Swedish immigrant who worked at a Wisconsin cottage cheese factory and lived in a double-wide trailer. Missing were his years growing up in Lake Forest, a wealthy suburb north of Chicago, the son of a top executive at Motorola. Rauner rowed crew at Dartmouth, where he studied economics, and earned his MBA at Harvard. He graduated in 1981 and moved to Chicago to take a job at Golder Thoma Cressey, or GTC, a private equity firm founded two years earlier by a trio who had worked together at one of the city’s top banks. A decade later, Rauner became a named partner and an R was added to the firm’s acronym. It was now GTCR.

Private equity firms invest in businesses in exchange for an ownership stake, like venture capitalists, or buy up struggling businesses that the partners think they can turn around. Over the years, GTCR seemed to specialize in the dull and ordinary. It invested in outdoor advertising, hospital management, steel tube manufacturing, fleet refueling, check authorization, and funeral homes because, Rauner once told a reporter, it produces profit margins of 35 to 40 percent and is “immune to downturns.” Rauner and his partners were similarly drawn to the coin-operated laundromat business because of what he described as a “locked-in customer base.” “If prices go up, the tenants still use it,” Rauner said.

Private equity is GTCR investing $7 million in a company called American Medical Lab and making $200 million when Quest Diagnostics buys the company for $500 million five years later in 2002. Or, as Rauner boasted about in a 2003 interview with Crain’s Chicago Business, paying $100 million to buy a subsidiary from one large company and selling it to another six months later for nearly $500 million.

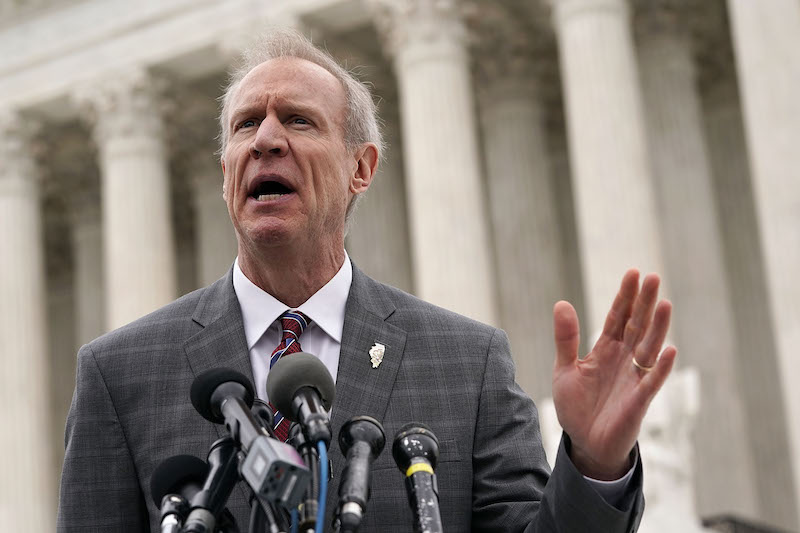

Governor of Illinois Bruce Rauner speaks to members of the media in front of the U.S. Supreme Court after a hearing on February 26, 2018 in Washington, DC. Image: Alex Wong/Getty Images

Other investments fail. That’s private equity, too: dropping $200 million on a company or a sector that collapses.

Then there are the deals that really give private equity a bad name — and make it a questionable way to invest public pensions. A health care company GTCR bought in 1998 was accused of stripping resources from the chain of nursing homes it owned — and then sued over its alleged participation in a scheme to avoid liability for a string of deaths. Another GTCR-owned company providing telephone services to the hearing- and speech-impaired paid $15.75 million to settle allegations by the Federal Communications Commission that it had overcharged customers. The SEC and Department of Justice caught another GTCR-backed company using a Bermuda-based subsidiary to skirt domestic stock-trading laws. Rauner’s firm extracted $9 million in cash from one of its portfolio companies right as the company was heading into bankruptcy, but was later ordered to pay more than two-thirds of it back.

Job losses are common when private equity firms implement “efficiencies.” In 2008, a GTCR-backed company that provides airport services snapped up several smaller rivals, including one operating a small regional airport outside of Chicago. At that one airport, the executive director of the operating agency said, the transition “from a small family business to a large corporate chain” translated into “a 30 percent reduction in workforce.” It’s also not uncommon for private equity to load up companies they buy with so much debt that they collapse under their own weight. In 1999, GTCR sold a Dallas-based wireless concern to a larger company — another big revenue generator that earned the firm more than $500 million on an $8 million investment. Yet the sale left the wireless company so freighted with debt that it was forced into bankruptcy shortly after the sale.

Private equity is a game of winners and losers, and the extent of Rauner’s winnings became clear only once the financier-turned-candidate released excerpts of his tax returns. The Rauners claimed a mere $28 million in income in 2011 and $27 million in 2010, but made up for down years with $53 million in 2012. Because of the carried interest loophole, Rauner likely paid only 23.8 percent in federal taxes on the bulk of his earnings — 40 percent less than what he would have paid if his earnings had been taxed as income.

A Black Box

The track record of firms such as Rauner’s has spurred some to question whether private equity, even when it outperforms other assets, is appropriate for a pension fund. Among them is Edward Siedle, a former SEC attorney who has been hired by a variety of public and private pensions to examine their portfolios. “It’s the public’s money being invested, yet the contracts with private equity firms routinely forbid an investor from sharing details about their holdings,” Siedle said.

These investments are so opaque that a top executive at the California Public Employees’ Retirement System confessed in 2015 that he had no clue how much in fees they were paying to private equity firms each year. The answer CalPERS arrived at several months later was an eye-popping $1.1 billion in the prior fiscal year. Private equity funds typically require nondisclosure agreements — problematic for an investment involving public funds — and the contracts are so one-sided as to be comical. A contract the Kentucky Retirement System inked with Blackstone, a giant of the private equity world, waives any liability on the part of the firm for engaging in financial conflict of interests. Another provision dictated that if management is sued, the costs “would be payable from the assets of the Partnership” — in other words, pensions and other investors would pick up the costs, not the general partners.

Hedge fund investments carry the same baggage. The contract a pension signs with a hedge fund typically forbids pension officials from revealing much, if anything, about the investment, even to the public employees on whose behalf a trustee is investing. The pension fund trustees who have decided to avoid buying stock in a gun maker, say, might not know that it owns some anyway through a hedge fund. More than 20 pension funds were in a fund of funds that included SAC Capital, the infamous hedge fund run by Steven Cohen, before the firm paid $1.8 billion in fines for insider trading and shut its doors.

For a fund like TRS, these provisions mean nearly 40 percent of its portfolio “operating entirely outside of scrutiny,” said Siedle, who refers to private equity as a “black box.” A firm might claim $200 million in profit on a $500 million deal, but how many millions were already siphoned off by means of “monitoring fees” partners pay themselves for dispending their wisdom to their portfolio companies, or “accelerated monitoring fees,” the lump sum partners charge their portfolio companies if a quick sale cheats them out of several years of lucrative consulting services? “Private equity managers are the most secretive money handlers out there, charging extra fees wherever they can, running these opaque, illiquid, hard-to-value private investments,” Siedle said.

- “He doesn’t want to solve the problem because the pension is the battering ram he’s using to try and break the public unions.”

It irked Siedle that both Rauner and Romney were able to run for public office “without disclosing how they made whatever money they have stashed offshore.” Perhaps that’s why Siedle chose to publicly dissect GTCR’s most recent SEC filing on the Forbes website one week before the 2014 gubernatorial election. In the filing, the GTCR partners lay out some of the special provisions they’d granted themselves. For instance, they had given themselves the right to create a special “family and friends” side fund that invests alongside the firm’s main funds. Those designated friends of the firm would be allowed to invest on better deal terms than those granted to other limited partners, or sell an asset to the main fund on terms determined by the partners. “Selling the laggards to other GTCR funds in which public pensions invest? Seems possible based upon the firm’s SEC filings,” Siedle wrote. Additional language freed the firm to bill the limited partners for any consulting services they deem necessary “even if another person may be more qualified to provide the applicable services and/or can provide such services at a lesser cost” and allows them to “withhold information from certain limited partners or investors,” including from entities “subject to [the] Freedom of Information Act.” Siedle then lists some of the massive public pensions that have entrusted GTCR with their money, including TRS in Illinois, and various state pensions in New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Louisiana, and New York. “Why would dozens of public pensions,” Siedle asked, “agree to obviously unfair treatment?”

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, asked the same question, though her preoccupation is with pensions investing in private equity and hedge funds who financially support organizations that hurt labor. It was six years ago, Weingarten said, that the union launched an initiative to educate teachers’ pension trustees around the country about this risk. The union started holding seminars for trustees and producing a periodic “Assets Manager” report, the most recent of which, published in March, singles out 21 money managers who are rich in no small part because of the money they made off public pensions — yet now support organizations calling for pensions’ elimination. Several are generous donors to conservative think tanks such as the Manhattan Institute and Reason Foundation, both of which have staked out pensions as an issue. “Teachers collectively have influence over trillions of dollars in assets,” said Weingarten, “and we intend to use it.”

Lower fees might be one answer. In 2017, the union released a report called “The Big Squeeze” that looked at 12 of the country’s largest public pensions. Cut in half the fees charged by private equity and hedge funds, the AFT found, and the average fund looked at would have an additional $360 million a year to invest. Looking ahead 30 years, and assuming an annual interest rate of 6.6 percent, the average return for a large public pension in the U.S., according to Pew — that means an additional $2-plus billion for every $350 million saved.

How to Prolong a Crisis

Rauner had been governor less than six months when the Illinois Supreme Court thwarted his effort to slash the retirement benefits the state had promised to its employees.

Rauner already had a backup plan in place. A state can’t declare bankruptcy. But local governments can, through Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy. Rauner proposed changing state law to shift responsibility for the teachers’ pension to individual school districts, which could then file for bankruptcy protection as a way to dodge unpaid pension obligations. The gambit hasn’t gotten anywhere so far in Illinois, where a Democrat majority currently controls the legislature, but governors and legislators in other parts of the country could pick up the idea.

Illinois gubernatorial candidate J.B. Pritzker speaks during a round table discussion with high school students at a creative workspace for women on October 1, 2018 in Chicago, Illinois. Image: Joshua Lott/Getty Images

More than two years passed before the state passed its first budget under Rauner, and then only because enough legislators were scared that the schools wouldn’t open that fall that some Republicans crossed the aisle to overturn the governor’s veto. By finally approving a state budget in summer 2017, Standard & Poor’s declared at the time, Illinois had avoided the dubious distinction of becoming the first state the ratings agency ever saddled with a junk credit rating. As is, Illinois still has the lowest rating of any state in the country at BBB- , the final step before junk status.

Rauner left no doubt that he wanted a second term when he wrote a $50 million check to his re-election campaign halfway through his first term, in 2016. Again, he has the financial support of other hedge fund wealth, including $20 million from Kenneth Griffin. Yet this time, Rauner faces an opponent who is even richer than he is: J.B. Pritzker, with a net worth estimated at $3.2 billion.

Pritzker has promised that he would not solve the state’s budget woes by cheating the elderly out of money they are owed. “I believe it’s a moral obligation to live up to the commitments made to those who have been promised pensions,” Pritzker wrote in a candidate’s questionnaire from the Chicago Sun-Times. “While there’s no time to waste, Bruce Rauner has squandered three years with his unwillingness to compromise.”

Earlier this year, the nonpartisan Center for Tax and Budget Accountability in Chicago put forward a potential solution to Illinois’s seemingly unsolvable pension funding crisis, among the worst in the nation. Under its plan, said Martire, the group’s executive director, the pensions systems in Illinois would be 70 percent funded by 2045 “without cutting a dime in benefits.” Pritzker has endorsed the idea of refinancing the debt. But Rauner, the financier for whom these kind of deals are second nature, has not.

“He doesn’t want to solve the problem because the pension is the battering ram he’s using to try and break the public unions,” Martire said. “He needs to keep spinning the pension problem because he needs the unfunded pension liability to make the case that it’s the public unions that are destroying things in every state.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations, where Gary Rivlin is a reporting fellow.