The La Sal Mountains rise like ungainly totems above the red rock desert outside Moab, Utah. From afar the forested slopes and barren, rock-strewn peaks have none of the splendor of nearby Arches or Canyonlands National Parks, which together attract millions of visitors every year. Nor are they particularly easy to get to. Until recently there wasn’t even an official trail to the summit of Mount Tukuhnikivatz, whose Ute name is roughly translated as “where the sun sets last.” Ed Abbey, who spent several summers as a ranger at Arches, once described Mt. Tuk as an “island in the desert,” geographically distinct from the surrounding region; he said he felt compelled to climb it because no one else would bother.

In part because of its high elevation—rising to nearly 13,000 feet, while Moab sits at around 4,000 feet—the La Sal Range is home to an unusual community of rare plants. Nearly a dozen of its alpine plant species represent the only documented populations in the state of Utah, some of which are considered “critically imperiled” by the conservation group NatureServe. And then there’s the La Sal daisy, a small, resilient plant with a buttonlike flower, which grows nowhere else in the world.

Because of the area’s ecological significance, the U.S. Forest Service, in the late 1980s, set aside the 2,380-acre alpine zone, which is part of the Manti–La Sal National Forest, exclusively for scientific study and observation. Named for neighboring Mt. Peale—the highest peak in the Colorado plateau—and encompassing three summits, it is called the Mt. Peale Research Natural Area, and it is a remarkably unspoiled ecosystem.

This is by design. RNAs are federal lands that have been set aside to permanently protect vulnerable plant and animal species and for long-term scientific research—”a reference for the study of succession,” according to the Forest Service. The first RNA was established on Forest Service land in the 1920s, but the network has since been expanded and now includes lands held by the Bureau of Land Management, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service. All told, RNAs encompass more than four million acres of federal lands in 46 states. There are few federal land designations that afford such protections. The statute establishing RNAs for scientific research says these places must be kept in a “virgin or unmodified condition,” a benchmark that has become increasingly important in an age of accelerating loss of biodiversity and ecological disruption caused by climate change. In the case of Mt. Tuk, however, these conditions no longer seem to apply.

On a warm, clear day in mid-June of 2018, I climbed Tuk with Marc Coles-Ritchie, an ecologist with Grand Canyon Trust who has spent much of the past two summers documenting plant populations in the La Sal Mountains. As soon as we exited the pick-up truck, Coles-Ritchie was pointing out the non-native grasses that had colonized the meadow at the trailhead. For decades, the Forest Service has issued grazing permits to ranchers for use of this land. Coles-Ritchie picked up a stalk of Kentucky bluegrass, held it up in the sun, and commented dryly that the same species is found on lawns across America. “Ranchers and rangeland managers tend not to care about what kind of vegetation is here,” he lamented. “We do.”

As we climbed higher up the mountain, the non-native species quickly disappeared. Now there were purple and white columbine, mountaintop thistles, elkweed—a tall flamboyant plant that can live as long as 80 years and flowers only once in its lifetime—and stands of Engelmann spruce. Right around tree line, at about 11,000 feet, we spotted our first La Sal daisy, a cluster of three unassuming bronze-yellow flowers clinging to the hillside. If Coles-Ritchie hadn’t been taking photos and kneeling down to view the plants with a hand lens, I would have walked right past them. The flowers were surrounded by a thick carpet of alpine grasses, which Coles-Ritchie said could be decades, even centuries, old, and which play an important role in stabilizing the soil. There was no sign or plaque announcing that we’d entered the RNA, but we were well within the boundaries of the protected area.

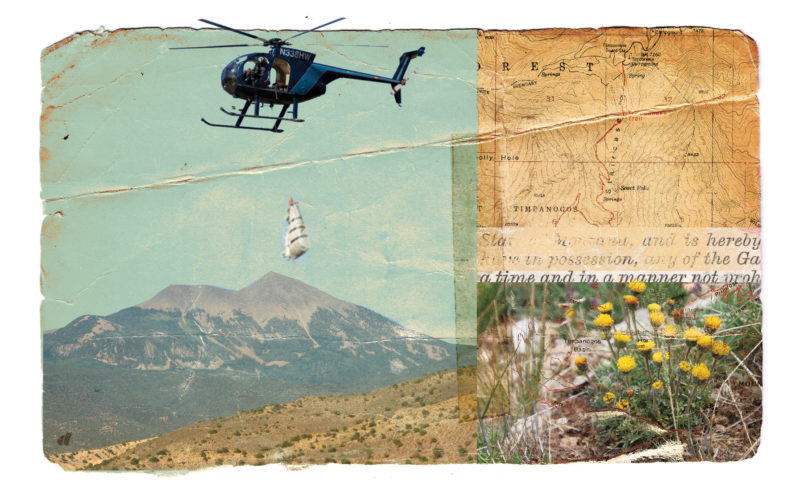

The La Sal daisy, which has long survived in this inhospitable environment and nowhere else, now faces a formidable threat. In August of 2013, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources transplanted non-native mountain goats onto a small chunk of state land about a half a mile from the RNA boundary, transporting them by helicopter and then by truck from the Tushar Mountains nearly 200 miles away. At the time, both state and federal officials expressed concern that the goats might end up in the alpine area, a violation of Forest Service policy, which prohibits the introduction of invasive species into research natural areas (in fact, the regulations require the agency to remove exotic plants or animals from RNAs). The Forest Service maintains that mountain goats, which were introduced to enhance wildlife viewing and sport hunting opportunities, are not an invasive species. Nevertheless, shortly after the goats were released, they moved up into the protected alpine habitat of the RNA and set in motion a series of changes that Coles-Ritchie says could threaten the integrity of the ecosystem and its value for scientific study.

Image: Illustration: David Vogin

But far more than the fate of this single flower hangs in the balance. The tiny La Sal daisy stands at the heart of an increasingly pitched battle over the future of public lands in the American West, one that could redefine the very character of America’s wild places. It all comes down to who has the authority to manage wildlife on public lands, and how much influence certain stakeholders wield. State fish and game agencies have long maintained that wildlife management is primarily their domain—even on federal land. Based on the legal principle of sovereign ownership, the states argue that they have the right to regulate and manage wildlife within their borders, and that federal land management agencies are responsible only for habitat. This rationale was used by the Utah DWR to justify releasing goats so close to the Mt. Peale RNA. “They [federal agencies] manage the land, and we manage the wildlife,” said Justin Shannon, a wildlife program manager for the Utah DWR at a May of 2013 meeting. The same argument has been made by states across the American West to justify stocking alpine lakes on federal land with non-native trout and to allow the hunting of predators, such as wolves and bears, in some national parks and wilderness areas.

The courts, on the other hand, have consistently ruled that the federal government, whose laws tend to be more restrictive and conservation-oriented than the states’, has the final say on issues concerning wildlife management on federal land. The Supreme Court has called the sovereign ownership argument used by the states to challenge federal authority a “19th-century legal fiction.” In 2017, Grand Canyon Trust and the Utah Native Plant Society sued the Forest Service, arguing that it failed to act to prevent the goats from entering the RNA, thereby abdicating its responsibility to protect the ecosystem from disturbance. In oral arguments before the 10th Circuit Court, the Forest Service said that states have primary authority over wildlife management, and that because the goats were technically released on state land, the agency’s hands were tied. While the Mt. Peale RNA represents a tiny, isolated patch of habitat, conservation groups including The Nature Conservancy and Defenders of Wildlife are worried that the situation sets a precedent that could undermine protections for threatened and endangered plant and animal species on public lands across the country.

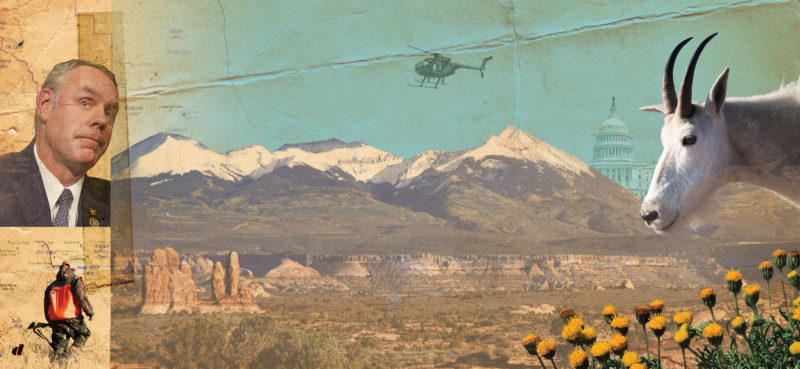

They are right to be concerned. In September of 2018, the Department of the Interior, which includes the Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, and the Bureau of Land Management (the Forest Service falls under the Department of Agriculture), issued a memo from then-Secretary Ryan Zinke, instructing each of its bureaus and offices to rewrite regulations governing fish and wildlife conservation so that they better align with state policies.

Michael Diem, a Moab district ranger who has been with the Forest Service for more than 40 years, says he’s never witnessed the sort of discord that has followed the state’s decision to transfer goats to the La Sal Mountains. This is in part attributable to Moab’s deeply rooted and outspoken community of environmental activists. Diem says the Forest Service has had a good working relationship with the state, and he seemed nonplussed by Grand Canyon Trust’s concerns about the goats destroying the alpine habitat (he was also limited in what he could say because of the lawsuit). The Forest Service and the state have a joint five-year monitoring plan to determine if the rare plants and ecological processes of the RNA are being damaged. After four years of collecting data, the Forest Service says it has not yet drawn any conclusions about the effects on plant populations; the data does, however, show a growing number of mountain goats in the study areas. But Diem declined to say what kind of impacts would trigger agency action or what those actions would look like. When I asked him about this, Diem said, “I don’t think we’ve ever identified any kind of threshold.”

In 2017, Coles-Ritchie surveyed 52 plots in the RNA to evaluate the impact of mountain goats on the alpine habitat. His findings were stark. Nearly 60 percent of the sites surveyed had declined in condition over the previous two years. Some had gone from being classified as pristine to “significantly degraded.” There were frequent sightings of the animals, as well as widespread evidence of their presence, including goat droppings and clumps of bleached white fur stranded in the turf grass. Perhaps most troubling were the extensive signs of wallowing, where the goats had removed most of the vegetation in order to roll around in the dirt—a high-elevation dust bath. Since goats often return to the same wallowing spots, it can take many years for the alpine plants to grow back, and these areas may be scarred for decades, if not longer. Coles-Ritchie found that the goats, year-round residents of the high alpine zone known for its short growing season and shallow soils, had begun to indelibly alter this once-protected landscape.

The concerns of wildlife, and what today we would call conservation biology, were not central to public lands policy when agencies like the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management were founded. These agencies were established specifically to manage federally owned resources—timber, grazing pasture, and, of course, oil, gas, and mineral commodities. Aldo Leopold, who worked for the Forest Service in the early part of the century before becoming a leading voice in the conservation movement, met resistance when he tried to convince his superiors that the needs of wildlife should be an important part of the agency’s mission. Decades after the Forest Service established a Division of Wildlife in 1936, according to historian Samuel Hays, it “continued to display a marked absence of leadership and a lack of agency competence” on the matter. In many cases, state fish and game agencies, along with hunting and angling advocates, stepped in to fill the void. Over time, this has led to long-lasting tensions over wildlife management.

Because state fish and game agencies derive most of their funding from the sale of hunting and fishing licenses and taxes on firearms and fishing equipment, they have a vested interest in boosting big-game populations, often at the expense of other conservation needs. Even as the number of hunters nationwide has declined in recent years, the power of the hunting and gun-rights lobby has become more entrenched. In 2017, for example, revenue from sport hunting and fishing made up a whopping 78 percent of the Utah DWR’s overall budget, and pro-hunting groups have helped fund goat introduction efforts across the state. Meanwhile, Utah, along with more than a dozen mostly western states, has no legal protections for rare plants and devotes almost no funding to studying them. When it comes to choosing between expanding the mountain goat population—a single tag can fetch as much as $1,500 for the state, and thousands of hunters apply annually—or protecting a plant that few people have ever heard of, the choice, at least for state fish and game agencies, is clear.

Nevertheless, the Utah DWR remains optimistic that the goats will not adversely impact the alpine plants: “We are confident that through careful management we will be able to responsibly manage this herd,” a spokesperson from the DWR said.

Publicly, the Forest Service has been overwhelmingly deferential to the states on wildlife management, but within the agency there have been sharp disagreements over the legal and environmental costs of doing so. In 2001, Peter Landres, then an ecologist with the Forest Service’s Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, published a paper looking at the agency’s authority to limit fish stocking in wilderness areas (which, like RNAs, can be designated in national forests, national parks, wildlife refuges, or on BLM land). For decades the Forest Service has allowed state fish and game agencies to introduce non-native fish into protected habitats for recreational purposes. As a result, thousands of high-elevation alpine lakes across the West, many of them once fishless, have been stocked with trout. Research by Roland Knapp, a biologist at the University of California–Santa Barbara, has shown that the introduction of trout by state agencies into alpine lakes in the Sierra Nevada, including lakes in the John Muir Wilderness and Kings Canyon National Park, has been a leading factor in the massive die-off of native amphibians, such as the mountain yellow-legged frog. (More than 60 percent of all lakes in the John Muir Wilderness, which is managed by the Forest Service, were stocked with fish in the mid-1990s.) The fish compete for habitat with and also prey on the amphibian larvae, which has led to catastrophic declines. In 2003, the Forest Service itself concluded in a review of ongoing research that, “the effects of a single human activity, fish stocking, have drastically changed these ecosystems.” Yet the practice continues. Every two years, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife drops tens of thousands of trout into the state’s alpine lakes, including several lakes in the Three Sisters Wilderness.

Image: Illustration: David Vogin; Source Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

It was into this charged atmosphere that Martin Nie, a soft-spoken professor of natural resource policy at the University of Montana, dropped a bombshell in the form of a 136-page research paper. In June of 2017, Nie posted a draft of his legal analysis, which had nearly a thousand footnotes and vastly expanded on Landres’ earlier research. Titled Fish and Wildlife Management on Federal Lands: Debunking State Supremacy, the paper, supported by a Forest Service research grant and written with a team of authors including former BLM and Forest Service officials, methodically picked apart the premise that states have the primary authority to manage wildlife on federal land. “The myth of state supremacy,” as Nie characterized it, was not only legally questionable but had led “to fragmented approaches to wildlife conservation, unproductive battles over agency turf, and an abdication of federal responsibility over wildlife.”

A few days after posting his paper, Nie ventured into the remote Mission Mountains Wilderness, a range of snow-covered peaks in western Montana, for an overnight: his gift to himself after two years of exhausting research. He returned from this short trip to a voicemail box full of messages from the dean of the university’s school of forestry informing him that the paper had caused an uproar, and that the Forest Service wanted him to remove any references to the agency’s funding of the project. The following day, the Forest Service asked the university to remove the paper from its website. The university, in consultation with Nie, refused to comply with the request. Nie would welcome feedback from the agency—his reason for posting the draft in the first place—before submitting a final version to the Environmental Law Review, he said. In a June 7th email to the Forest Service, the dean wrote that “removing the article from the website … would constitute a form of censorship which stands to stifle academic freedom, creativity, and process.” A Forest Service employee responded ominously that he hoped the “consequences of this decision will not be as serious as I fear they will be.” After a flurry of letters between Nie, the university, and Forest Service officials, the agency terminated its contract with Nie.

Nie had written about hot-button issues in the past. His first book, Beyond Wolves, published in 2003, looked at the controversy surrounding wolf recovery programs in North America. A few years later he published a paper on resource management in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, which he described as “one of the most enduring and intractable environmental conflicts in the United States.” But nothing prepared him for the backlash that greeted his work on state authority and wildlife management.

Nie expected the paper to raise some eyebrows, but he was still stunned by the Forest Service’s response. He’d served for several years on a Forest Service advisory committee, and has a signed letter of appreciation from former agency chief Tom Tidwell. Plus, the grant for the paper had come from the Forest Service itself. People within the agency knew he was planning to tackle a controversial subject and had chosen to support his research anyway.

But the paper had come out in the early months of the Trump administration, which had promised to aggressively curtail the regulatory authority of federal agencies, especially those overseeing the environment and public lands. Early on, the administration reversed a rule that had prohibited the state of Alaska from baiting and killing bears and wolves in wildlife refuges, a practice that had been viewed by the Fish and Wildlife Service as a clear violation of federal policy. President Donald Trump also dramatically reduced the size of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monuments in Utah, which was widely seen as a gift to those who favor limiting federal oversight of public lands. Meanwhile, changes to the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and sage grouse management have been proposed that would grant more power to state and local authorities. Nie’s legal analysis and rebuke of state supremacy may have been long overdue, at least in the eyes of many federal employees and conservationists around the country, but it wasn’t going to find a receptive audience in Washington.

According to hundreds of pages of documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, senior-level officials at the agency urged employees not to share the Nie paper. Soon after the paper was posted, the Forest Service issued talking points to its employees to clarify its position on the paper. On June 6th, Robert Harper, national director for water, fish, wildlife, air, and rare plants, sent an email to colleagues saying, “I know this is on line but please don’t share.” Later that day, on behalf of the chief of the Forest Service, a high-ranking deputy requested answers to questions about the contract, including who should be held accountable for it and what was being done to ensure that “this mistake is not repeated.”

Nevertheless, according to documents received via FOIA, the paper circulated widely within the Forest Service, and some of the agency’s employees saw it as an affirmation that the agency has far more power and authority vis-à-vis the states than it has been willing to exercise. In one email, Forest Service fish biologist Scott Spaulding said he read the paper with interest. “Have been told all along we have broader authorities than generally redeemed when dealing with states on wildlife and conservation management issues,” he wrote. But the Forest Service didn’t seem interested in using the Nie paper as an opportunity to reexamine its own policies and practices. Instead, the agency demanded that Nie remove any acknowledgment of its support for the paper and embarked on a concerted effort to bury it.

Nie’s paper called out several federal land management agencies, including the BLM and the Forest Service, but was especially critical of an organization that few people have ever heard of: the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, which represents all 50 state fish and game agencies and works closely with federal agencies. The AFWA has, in recent years, zealously pursued a legal strategy to expand state power over wildlife management and public lands. Carol Frampton, the AFWA’s former legal counsel and a longtime National Rifle Association board member, led the charge, presenting state fish and game agencies as perennial victims of federal overreach. (Frampton has remained involved in the AFWA’s education programming.)

In November of 2017, the AFWA filed an amicus brief on behalf of the Forest Service in the Mt. Tuk mountain goat case, arguing that a decision favorable to the conservation groups would “cut deeply into reserved State authority to manage wildlife.” The AFWA referred to concerns about habitat degradation as “unsubstantiated.” (Nie filed an opposing brief in the case.)

Founded in 1902, the AFWA has a broad membership base that includes federal agencies—the FWS and the BLM are both members—and various hunting and conservation groups. The Boone and Crockett Club, Safari Club International, the National Audubon Society, The Nature Conservancy, and the NRA are all contributing members. But the AFWA’s core constituency is the state fish and game agencies—all 50 of them are dues-paying members, and they provide the bulk of the organization’s annual operating budget of about $5 million. Through leadership positions within the organization, state fish and game agencies drive policy positions on a range of issues, from migratory birds and the Endangered Species Act to hunting and fishing regulations and species conservation. Nie had singled out the AFWA because of the outsized success he says it’s had in influencing federal policy—it even had a liaison embedded in the Forest Service for a time.

“We try to make sure that when there’s rule-making occurring or new policy being set that state issues are being addressed,” said Ron Regan, the AFWA’s executive director. Because state fish and game agencies work closely with their federal counterparts on a host of conservation issues, the AFWA has often had a seat at the table in formulating federal policy. The fact that they also lobby those same government agencies puts them in an unusual position. In 2006, for example, the AFWA renegotiated a longstanding agreement on fish and wildlife management in wilderness areas that some of the government’s own lawyers felt betrayed the intent of the Wilderness Act. According to Nie, the agreement made it easier to introduce non-native species into wilderness areas, eased prohibitions on activities allowed in those areas, and generally gave more power to the states to manage wildlife on federally protected land. The agreement, one Department of the Interior solicitor wrote, fails to recognize that “[f]ederal law, including regulations and discretionary actions, preempt[s] state jurisdiction.” Despite internal pushback, the leadership of the BLM and the Forest Service signed the new agreement. “It was a huge, huge change essentially dictated by AFWA,” said Chris Barns, a BLM wilderness specialist who retired in 2015 and is one of Nie’s co-authors. Ron Regan takes issue with those who say the agreement gives states more power and makes it easier to introduce non-native species. “I know there are some folks in the government who felt like they gave up some things,” he said. “But I don’t think anyone’s feet were held to the fire. It was a collaborative effort.”

Though Regan describes the AFWA as non-partisan, it has had some high-profile successes advocating for the expansion of state authority under Republican administrations, which tend to favor limited government. In a briefing memo drafted for the deputy director of the FWS and obtained through FOIA, Regan referred to “the deterioration of relationships with the previous administration,” and said the AFWA was eager to forge a new partnership with the Interior department under Trump. The AFWA was often at odds with the Obama administration, and blasted the decisions by the FWS and the NPS to regulate hunting in Alaska’s wildlife refuges and national parks. The group also railed against the administration’s decision to prohibit the use of lead ammunition, which poisons and kills millions of birds and animals annually, in wildlife refuges, describing it as “unacceptable federal overreach.” The order was reversed on Zinke’s first day in office, and an AFWA representative attended the signing ceremony.

Image: Illustration: David Vogin; Source Photo: Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images

The AFWA has also lobbied for “improvements” to the Endangered Species Act that would give states more control over whether to list species as threatened or endangered. In October of 2017 Greg Sheehan, then acting director of the FWS and the former chair of the AFWA’s committee on threatened and endangered species policy, issued a memo increasing the number of state representatives on the teams that make such determinations. Not surprisingly, the AFWA strongly disagrees with the Nie paper. An AFWA spokesperson said the group is preparing a “long overdue article” on the subject but would not say when or where it will be published. According to Regan, “I think we do want to try to set some facts straight from our perspective on federal reach and … the historical-legal backdrop for managing fish and wildlife in this country.”

Meanwhile, the AFWA continues to pursue its mission to “restore state authority.” Shortly after Trump was elected, the group issued a list of legislative priorities for the administration’s first 100 days. No. 1 was establishing a new executive policy “affirming and recognizing state agency authority for management of fish and wildlife within their borders.”

That wish, by and large, has been granted. At the AFWA’s annual meeting in Tampa last September, Aurelia Skipwith, the Department of the Interior’s deputy assistant secretary for fish, wildlife, and parks, unveiled a memo, signed by then-Secretary Zinke, parts of which strongly resemble language used in AFWA planning documents (according to Ron Regan, the Department of the Interior [DOI] had reached out to the AFWA in the spring and had given the organization the opportunity to offer input on the plan). The memo gave DOI bureaus, which manage nearly a fifth of all lands in the U.S., 90 days to review all regulations and policies that “are more restrictive than otherwise applicable State provisions for the management of fish and wildlife” and to draft recommendations for overhauling those regulations to better align with the state provisions. According to a spokesperson with the FWS, the department is moving forward with the memo as planned, and the BLM, in a written statement, said the bureau continues to “have conversations with our state counterparts on this important issue.” The memo, which referred to the states as “stewards of the Nation’s fish and wildlife species on public lands,” was applauded in an AFWA press release for reaffirming the “primary authority of state fish and wildlife agencies to manage fish and wildlife within their borders, including on DOI land.”

Don Barry, who spent nearly 19 years at DOI as a career attorney and as assistant secretary, said the memo essentially dispenses with decades of established policy on wildlife management and conservation outlined in the obscure but important federal regulation known as 43 CFR Part 24. The regulation, drafted in the wake of a number of court decisions and congressional enactments that had expanded federal authority, sought to clarify state and federal jurisdiction over wildlife management. (“Modernizing” this policy was another one of the AFWA’s top priorities for the Trump administration’s first 100 days.) Barry says the regulation already makes numerous concessions to the states on fish and wildlife management but that it delegates final decision-making authority to the FWS and the NPS. Even under James Watt, Ronald Reagan’s Interior secretary, Barry says, DOI lawyers were able to fend off an effort to weaken the policy, which was revised and updated in 1983. At the time, Barry was the head attorney for the Fish and Wildlife Service. “There was a heavy push to water it down and to change it,” Barry said. “We pushed back.” But he has serious doubts as to whether the current DOI solicitor’s office will be willing to stand up to the most recent attacks.

The sweeping changes outlined in the memo, if implemented, could dramatically change the way America’s wildlife refuges and national parks are managed, according to Barry. The recent reversals of FWS and NPS rules in Alaska, which gave the state the authority to kill wolves and bears on federal land, could be adopted elsewhere. We can expect to see an increased emphasis on game management at the expense of conservation and species protection. And the new rules could undermine wildlife protections that have been in place for more than 50 years. Conservation groups will almost certainly attempt to sue over the new regulations; Defenders of Wildlife called Zinke’s proposed outsourcing of the department’s responsibilities to the states “both inappropriate and illegal.” The memo itself constitutes an unprecedented attempt to weaken federal authority on public lands controlled by the FWS and the NPS while granting state governments more power over wildlife management and conservation policy. For his part, Ron Regan says the changes should be viewed as an attempt to restore balance between federal and state agencies. “To some it might appear as some new grab by the states, but from our perspective, it’s about recognizing the traditional or historical view on these issues,” he says.

A couple of weeks after the memo was released, Utah’s 10th Circuit heard oral arguments in Grand Canyon Trust’s lawsuit against the Forest Service. Aaron Paul, the Trust’s attorney, opened by explaining that the Mt. Peale RNA, at least until recently, had become a “benchmark for what a high alpine region in the desert southwest should look like.”

In some ways it still is. The rare plants, which have been protected for decades, are still there. And it remains the only place in the world to see the La Sal daisy. But when I hiked up there with Coles-Ritchie in June, he said he was shocked to see the extent of the damage. It was his first trip into the RNA since he’d conducted his fieldwork the previous summer, and there seemed to be significantly more disturbed vegetation, scat, goat fur, and wallows. In places, the ridgeline, marked by hoofprints and exposed soil, had come to resemble a kind of alpine pasture.

And these already visible impacts are about to get worse. In 2017, when Coles-Ritchie conducted his survey, there were only some 70 goats grazing in the alpine area. Under the state’s management plan for the La Sal Mountains, that number is expected to more than double over the next few years.

As we made our way up above tree line and toward the saddle between Mt. Peale and Mt. Tuk, Coles-Ritchie took dozens of photos to serve as evidence of the profound changes taking place. In a tone that was halfway between a question and a statement of fact he said, “We’re going to document the disappearance of this alpine habitat.”

Then, as he wandered off to snap photos of yet another wallow, he said, “We are documenting it.”

This project was reported in partnership with Type Investigations.

Illustrations by David Vogin.