In 2015, Sabrina Martinez got into the University of Texas at Austin, the UT system’s flagship campus and its most selective. She was thrilled. Her parents, not so much. “They were just like ‘Nope. You can’t afford it. You shouldn’t go. Loans are ridiculous.’” They encouraged her to go to the cheaper University of Texas at El Paso, to which she could commute while living at home. “But I clicked ‘accept’ on my admission anyway,” she says, figuring that attending UT Austin’s lauded journalism school would lead to more internship opportunities and, ultimately, a job after she graduated.

Martinez’s parents are divorced. Her mother works as a teacher and receives child support from her father, who works in the oil fields of West Texas. Her family always had money for necessities, Martinez says, but with her two younger siblings to take care of, there usually wasn’t much left over for luxuries. That meant paying for college fell squarely on her shoulders.

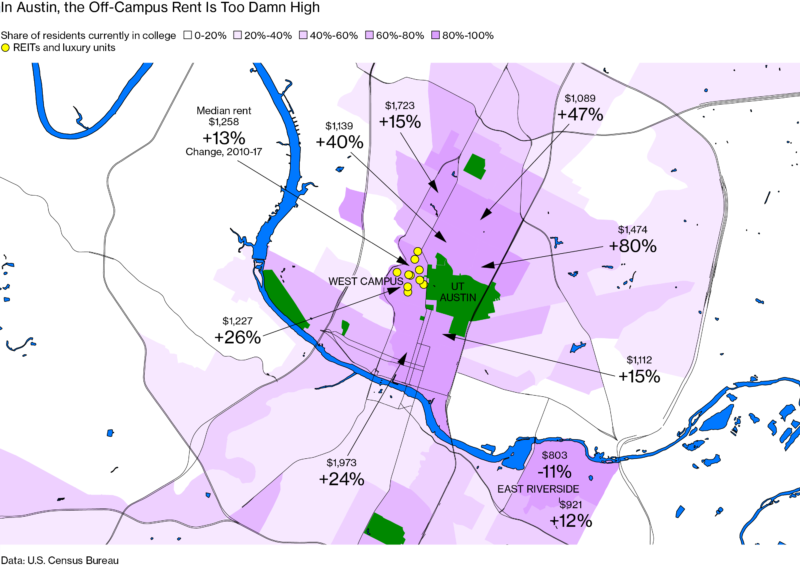

Even with student aid, a $5,000-a-year scholarship, and some income from a part-time job on campus, Martinez has had to take on far more debt than she expected. She’s hardly alone: Average student debt has climbed from about $11,000 in 1990 to more than $35,000 in 2018. The cost of tuition at public colleges roughly tripled in that time, to $10,270, but that’s far from the only expense forcing students to take on loans. In a 2015 analysis, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development found that “housing costs [are] likely a significant portion” of individual student debt. At UT Austin, the median annual rent in the neighborhoods closest to campus exceeds the annual in-state tuition—about $11,000 for the upcoming academic year—even without including other costs such as utilities and groceries.

Martinez chose to live in a dorm her freshman year at a total cost of more than $10,000, which included a meal plan. As at many public universities, UT Austin’s enrollment vastly exceeds its housing capacity, so most students opt to live off campus after their first year. The closest student neighborhood is West University—West Campus to locals—which would have been a 10-minute or so walk from most of Martinez’s classes. In 2017, the year she was apartment hunting, median gross rent, which includes the cost of utilities, in West Campus was about $1,200 per month, according to U.S. Census Bureau data, far more than she could afford. Instead, she moved to East Riverside, which is farther from campus but where the median gross rent was a comparatively reasonable $862 per month.

UT Austin says it doesn’t keep exact numbers on students living in East Riverside, but the neighborhood is popular enough that the city runs a direct bus route between the neighborhood and the university. The bus operator, Capital Metro, estimates that more than 2,400 UT students live in the neighborhood. On a good day, Martinez’s commute to campus is about 25 minutes, but during rush hour it can take an hour or more. “Around 5 p.m. is when people usually get out of class, and that’s a heavy time for traffic,” she explains one morning as the bus crawls along a clogged I-35. “You can never find a seat, so people usually fight to be first on the bus. It’s pretty rough.”

Portrait of Sabrina Martinez, a senior studying journalism, in her apartment in Austin, TX on February 1, 2019.Image: Photograph by Bobby Scheidemann for Bloomberg Businessweek

Median gross rents in West Campus in 2017 were 37% higher than in 2009, a sharp increase compared with East Riverside, where the rents were roughly flat for the period. From 2000 to 2017, Austin’s population climbed about 45%, according to the Census Bureau and the City of Austin, as demand for housing contributed to a 72% surge in average rents. West Campus median gross rents outpaced the city as a whole, rising more than 87% in the same period.

Population growth is almost certainly part of that increase. But the dramatic rise in rents also coincides with national developers starting to eye the areas around public universities as a growth market. Real estate companies bulldoze aging buildings to put up the kinds of amenity-rich, luxury apartments that might appeal to upper-middle-class parents looking for a safe, comfortable place for their student to live but which students from lower-income families such as Martinez’s couldn’t possibly afford.

What counts as “luxury” is subjective, but these kinds of developments offer a standard of living largely unseen by students in previous decades. “The rise of luxury student housing can have perverse, unintended consequences,” says Thomas Laidley, a doctoral candidate in New York University’s sociology department who’s researched urban stratification and inequality. These pricey apartments force less wealthy students farther away from campus, and longer commutes can hurt students’ grades and chances to graduate, according to research cited by HUD.

The result is to divide student populations along lines defined by family wealth. Those who fall on the wrong side feel the difference. “I would probably go to more events on campus or join more groups, because I wouldn’t have to rush home or take an hourlong bus ride home,” says Martinez, who estimates she’ll graduate with $75,000 in student debt. “If there’s an event at 7, and I get off at 5, I’m not going to want to wait two hours. I feel cut off from the UT experience.”

The phenomenon isn’t limited to Austin. The areas around the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, and Colorado State University at Fort Collins have all seen luxury options proliferate and affordable ones disappear. Often the companies behind them have been structured as real estate investment trusts, or REITs—properties or mortgages that are bundled and sold in shares to investors, reducing the developer’s corporate tax burden.

The pioneer of building luxury student housing at scale is Bill Bayless, co-founder and chief executive officer of American Campus Communities. ACC is headquartered in Austin, about a 40-minute drive from West Campus, where it owns more than a dozen properties. When Bayless started his company in 1993, his model seemed risky. By then-conventional wisdom, college students were fickle and irresponsible and guaranteed to leave in four years, give or take, forcing landlords to find new renters. It seems obvious now, but Bayless was among the first to realize that there will always be more students to replace those who leave. Over the next two and a half decades, ACC put up luxury student housing and renovated existing properties in dozens of cities. ACC went public in 2004 and by 2018 had acquired $5.9 billion of property.

“ACC is definitely one of the grandfathers of this industry,” says Ryan Tobias, a founding partner at Triad Real Estate Partners, a brokerage company that specializes in “premier” private student housing and multifamily real estate. A wave of similarly styled companies focusing squarely on high-end student housing followed. Two of ACC’s biggest competitors, Education Realty Trust, or EdR, and Campus Crest Communities, went public in 2005 and 2010, respectively. EdR was acquired by Greystar Real Estate Partners in 2018.

Image: Bloomberg Businessweek

The rise of ACC and its imitators tracks with an overall increase in student housing costs. Around the 1980s, state funding for higher education stopped keeping up with inflation. This left universities without enough cash to fund new-housing construction, or even sometimes to keep up with basic maintenance on existing units, according to a 2015 report by HUD. “Universities used to see developers as competition,” says Robert Silverman, a professor in the University at Buffalo’s urban planning department. “Now they see them as a solution.” From 1989 to 2017, the estimated cost of on- and off-campus room and board at a four-year public university climbed more than 82%, adjusted for inflation, according to numbers compiled by the College Board. Rents across the entire U.S. climbed only about 19% in the same period, also adjusted for inflation.

How much responsibility REIT and luxury developers bear for driving up rents depends on whom you ask. Developers and their allies say they’re simply offering more places for students where there are few options. But a Bloomberg analysis of rental rates based on census data shows a correlation between the arrival of luxury student housing development and rising rents near UT Austin and the University of Michigan, each of which has particularly well-defined student housing areas.

- ‘You have to come from a rich family, basically, if you want to have the luxury of living near campus and interacting with other students more.’

Real estate management company CWS Capital Partners LLC was one of the first to build large-scale luxury apartment buildings in Austin’s West Campus neighborhood. From 2000 to 2010, the company built enough units to house 2,000 students; in that time, median gross rents in West Campus shot up more than 56%, to $1,040 per month, more than double the 24% increase in Austin as a whole during the period. In another nearby neighborhood, North University, which saw no new luxury construction, rents rose 32% in that period. CWS did not return requests for comment. ACC began acquiring those properties in 2012. It now houses as many as 34% of the students in West Campus and as much as 13% of UT Austin’s undergraduate population.

The data from Ann Arbor paint a similar picture. Most luxury housing near the university was built from 2010 to 2016; in that time, Ann Arbor census tracts that include REITs and luxury apartment buildings have seen their median gross rents rise 37%, to more than $1,400 a month. Rents in Ann Arbor generally have increased about 18%. In one census tract adjacent to the University of Michigan, median gross rents rose more than $1,200 a year in 2011, 2012, and 2015, coinciding with luxury projects hitting the market built by ACC, EdR, and a couple of local developers. Rents were flat in 2013 and 2014.

“It just seems wrong for us to pay as much as we do in tuition, and then if we want to be able to be near campus, we have to pay even more”

The areas around campuses are basically a constantly replenishing seller’s market. When a large number of people all want to live in the same place, developers can name their prices. Many universities, in trying to solve their funding shortfalls, have inadvertently exacerbated the problem by admitting larger numbers of out-of-state students, who pay more in tuition but who all need somewhere to live—and who are likelier to come from wealthier families and able to afford fancier housing. When student housing developments rent by the bed, they can usually squeeze more money out of a space than if they rented by the unit, which can further inflate real estate prices in the area.

In Seattle, which is already dealing with vertiginous rents, ACC owns three properties near the University of Washington campus and plans to build at least one more. From 2016 to 2017, rents in the so-called U District, a popular student neighborhood, rose 15%; rents in Seattle as a whole increased 6.3% in that time. ACC also built a student residence featuring a “state-of-the-art fitness center” and “gaming lounges” next to the University of California at Berkeley, where affordable housing is in severely short supply. UC Berkeley disputes that the ACC building is a luxury facility; the UW declined to comment.

Tonie Miyamoto, director of communications for student affairs at Colorado State University, says the university has a “housing master plan,” which involves new construction of affordable on-campus options. J.B. Bird, a spokesperson for UT Austin, said in an emailed statement that housing affordability for students is “of serious concern for the university” and that the school has “plans in the works to extend aid for living expenses.”

“The university hears often from students about the challenges of finding affordable housing in Austin,” Bird said. “The university is evaluating different steps to improve the situation for students while working closely with people and businesses in neighborhoods nearby.”

In the meantime, many UT students, especially those in East Riverside, are frustrated. “It just seems wrong for us to pay as much as we do in tuition, and then if we want to be able to be near campus, we have to pay even more,” says Mary Okon Itrechio, another UT Austin student who lives in Riverside. “You have to come from a rich family, basically, if you want to have the luxury of living near campus and interacting with other students more.”

The University of Michigan declined to comment for this story, and EdR didn’t acknowledge multiple comment requests. ACC spokeswoman Gina Cowart disputed the term “luxury” as applied to the company’s properties, saying ACC provides “quality communities designed for longevity and the student experience at competitive prices.” She also said students can apply to be resident assistants at ACC properties for a 25% reduction in rent as part of the compensation. Nationwide, Cowart said, the company had raised rents annually by a “very modest” 2.6% on average since the company’s 2004 initial public offering. In markets where student housing is harder to find, however, ACC has hiked rents by much higher percentages. From 2013 to 2017, rents at the company’s Austin properties went up 24%; in Ann Arbor, ACC raised rents in one building by 26% from 2012 to 2017.

Bayless says his company offers more affordable options than do his competitors, who often focus exclusively on luxury units. “We have always focused on what we refer to as building for the masses, not the classes,” he says, adding that ACC’s shared rooms bring down the price of housing for individual students.

For students with limited means, living in an expensive unit closer to campus isn’t necessarily better. One of Sabrina Martinez’s friends, Dominique Lopez, works a total of 20 hours a week at two part-time jobs, in addition to being a full-time student, to be able to pay for her roughly $1,000-a-month West Campus apartment in a building that CWS built in 2014. Her rent is slightly lower than others’ thanks to a citywide affordable housing program, which helps some individuals from lower-income backgrounds live in higher-end buildings.

Lopez’s parents pushed her to live within walking distance of her classes, because they said it would help her grades, she says. She’s not sure if it’s been worth it. “I had been in several clubs, including the Pre-Physician Assistant Society. I had to drop that, though, after I started working to be able to afford to live near campus,” she says. “I feel like it’s hurt me professionally. It’s affected my ability to volunteer, be involved, and make a more competitive application for grad school.” Lopez says her parents help as much as they can, but she’s taken out loans that she’ll have to pay back after she graduates. “I had a breakdown as I was re-signing my lease,” she says, because of the pressure of paying for another year of rent. “But my parents talked me through it.”

Kathie Tovo, a member of the Austin City Council whose district includes West Campus, winces when she hears about Lopez’s rent. “That’s a lot. That’s a lot of money,” she says. Tovo has floated various ideas to make student housing more affordable but says she faces substantial resistance from developers. Mike McHone, a local real estate agent who represents some developers in the area, helped create the affordable housing program in West Campus that Lopez relies on, which allows developers who put in affordable units to build taller buildings. He dismisses the notion that nonmarket-based types of aid such as rent control are necessary to help students find better options. “Commodify all the commons,” he says.

More units haven’t benefited students such as Lopez and Martinez, who have to struggle to afford to live in them. “It’s a double-edged sword because, on one hand, you’re building housing for students which has been in short supply in a lot of places,” says NYU’s Laidley, the doctoral candidate. “But when you have shareholders, all they care about is how much money they’re making. It’s not their business to care if students get safe, fair housing.”

This article was reported in partnership with Type Investigations.

Correction: This piece was updated to reflect that ACC has plans for at least one more property near the University of Washington, not four.

8/14/19: Updated with comment from UC Berkeley in the 18th paragraph.