Gerry Armbruster went to the doctor in May 2014, complaining of tingling and numbness in his arms and hands. He told the doctor how pain in his legs was making it hard to walk, too. “I knew something was wrong, but I couldn’t pinpoint it,” Armbruster said. He says he was told by the doctor that he was just dehydrated and if he drank more water he would be OK.

Two weeks later, Armbruster was back; the pain and numbness had gotten worse. He now had no grip in his right hand. It took him five minutes to write his name on the paperwork given to him at the appointment. Over the following weeks Armbruster went to the doctor repeatedly, yet at each visit, medical staff would not refer him to a specialist.

Armbruster had no option for changing doctors or getting a second opinion: He could only see the doctor assigned to Southwestern Illinois Correctional Center, a 763-bed prison in East St. Louis, where he was serving a three-year sentence for burglary and aggravated battery.

Armbruster did not know he had signs of spinal cord compression, a dangerous condition that can cause permanent damage to the spinal cord, especially if not treated early. Though he spent the final five months of his sentence begging for medical staff to help him, relief did not come until after his release. Ten days after leaving prison, Armbruster found himself on the operating table, a surgeon racing to alleviate the pressure on his spinal cord.

Armbruster was only one in a string of patients who allege that they suffered after their prison doctor, Bharat Shah, missed critical symptoms and misdiagnosed common conditions. Just weeks after Armbruster’s emergency surgery, another prisoner arrived at the prison on a strict antibiotic regimen to keep a mild infection under control. Yet for months, the prisoner later told the federal court in Illinois, Shah refused to give the prisoner the medication, resulting in a severe ankle infection that had to be surgically removed. Months later, another prisoner at the same prison suffered nearly identical symptoms as Armbruster; Shah allegedly refused to treat him.

In court filings, Shah denied that he had provided negligent care. Armbruster’s case is still open, but the other two have been dismissed, one because the prisoner failed to complete the prison’s grievance process before filing his suit and the other because the plaintiff missed a court date.

Shah is far from the only doctor in America’s prisons to face these types of allegations. A joint investigation by Type Investigations and The Appeal that included interviews with prisoners, lawyers, advocates, and a review of hundreds of medical disciplinary records, prisoner medical records, and court filings found that doctors with histories of serious medical errors or past records of misconduct are hired to work in prisons across the country, and they often continue treating patients even after prison officials are made aware of problems.

Correctional healthcare is fraught with conditions that allow problematic doctors to flourish. It can be tremendously difficult to recruit physicians to work at prisons in rural areas, for example, so agencies often turn to specialized private companies for help. That’s what happened in Illinois, where the state Department of Corrections contracted with a correctional healthcare company, Wexford Health Sources Inc., to provide physicians and medical staff to work in the state’s prisons. These public-private partnerships often force the correctional agencies to cede control of hiring and firing individual physicians, and obscure the lines of responsibility when something goes wrong.

Even when a doctor’s mistake results in a permanent disability, prisoners have few options to seek better treatment or push for accountability. In addition to the limitations at the local level, a federal law passed in the 1990s placed restrictions on when a prisoner can sue over treatment. Together, these conditions create a climate of impunity for dangerous doctors, leaving an unknowable number of prisoners permanently disabled, and costing others their lives.

“No one cared,” Armbruster said of his treatment in prison. “They didn’t care … because I wore a blue shirt, blue pants, and an ID that says my name and number on it.”

A groundbreaking class action lawsuit filed in 2013 against the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) offers a glimpse behind the scenes of correctional healthcare. The case, brought by the ACLU of Illinois and the Uptown People’s Law Center in Chicago, alleged systemic failures in the agency’s medical services. It began in 2010 when Don Lippert filed suit, alleging that the insulin needed to manage his diabetes had repeatedly been withheld, which the IDOC denied. The federal court hearing the class action case appointed an independent four-person team of experts—two physicians, a nurse, and a dentist—to determine “whether the state of Illinois was able to meet minimal constitutional standards” in its healthcare program.

The team released its report in December 2014, and the results were scathing: The IDOC’s healthcare program hired “underqualified” physicians, failed to provide appropriate supervision and oversight, and did not have adequate electronic resources for physicians to manage care. These conditions resulted in at least 36 deaths between January 2013 and June 2014 and two deaths in 2010 that the team deemed “problematic.”

In 2017, as the case continued, the federal court appointed a second team of medical experts to update the court on the department’s progress.

The second team noted some improvements but found that Wexford failed to hire properly credentialed physicians, which increased the risk of harm to patients and led to nearly a dozen preventable deaths from 2016 to 2017.

- At least four doctors who were found to have one or more preventable prison deaths attributed to their care remained on staff in Illinois prisons.

Wexford’s chief administrative officer, Elaine Gedman, could not comment on any specific cases, but said the company disputed the findings in the expert reports. “We don’t think that it was a fair and accurate assessment of the care that is provided,” she said, noting “there are hundreds of thousands [of patients] that had no issue with any of the care that was provided.”

The expert teams studied the healthcare delivery in eight prisons and reviewed dozens of deaths. Type Investigations and The Appeal scoured the experts’ reports and mortality reviews and identified doctors that frequently reappeared. At least four doctors who were found to have one or more preventable prison deaths attributed to their care remained on staff in Illinois prisons: John Robert Trost, Saleh Obaisi, Vipin Shah and Kul B. Sood were identified by name in the class action case.

Two of those doctors are no longer treating incarcerated patients in Illinois. Trost no longer works for Wexford in Illinois, but while he was medical director at Menard Correctional Center at least four patients died under his care. Two of these deaths were deemed preventable, and two were found to be possibly preventable by the expert team. Obaisi had at least two patients die under his care in a little under a year—both deaths were deemed preventable by the expert team. Obaisi worked for Wexford in Illinois until his sudden death in December 2017. Trost did not respond to interview requests.

But Type Investigations and The Appeal found that two of the other doctors named in the class action—Sood and Vipin Shah—are still on staff.

Sood was the subject of several emails complaining about his performance. At Hill Correctional Center, the facility where Sood worked in western Illinois, the first expert team determined at least two prisoner deaths were “extremely problematic,” and involved “egregious” lapses in care.

Sood was the medical director at Hill Correctional Center in January 2013, when one patient came in complaining of abdominal pain. A doctor noted that the patient’s spleen was enlarged and encouraged him to drink more water and take some naproxen for the pain. By September, the patient was dead. The expert team noted that in the intervening nine months, there were “multiple and disturbing” lapses in his care. The patient had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but received that diagnosis at the intensive care unit of a local hospital only two weeks before he died.

The expert team wrote that the patient was displaying symptoms commonly associated with cancer, yet “it took four months to obtain the first appropriate imaging test (ultrasound). When that test suggested the need for more detailed imaging by CT scan, that recommendation was ignored, despite increasing clinical evidence of a serious underlying condition.”

According to the expert report, the death summary written by Sood “completely glossed over the significance of the enlarged spleen and focused mainly on the terminal events in the infirmary.”

The expert team concluded that the care could “only be construed as deliberate indifference.”

The second expert team found another preventable death under Sood’s watch. At Hill Correctional Center, a patient was put on blood thinning medications although he had multiple health conditions that made these drugs dangerous for him to use. As his health deteriorated, the patient began showing symptoms that the level of blood thinners in his system was too high; still the doctor did not check the level of medication in the patient’s blood. Eventually, the patient became unresponsive and was sent to the hospital where testing showed extra-high levels of blood thinner medication, which led the patient’s brain to herniate and caused his death in January 2016.

“This doctor is a nuclear radiologist and clearly does not have fundamental medical knowledge sufficient to practice general primary care medicine, and should not be allowed to do so,” the second court-appointed medical team wrote, referring to Sood. “This is a doctor identified on the First Court Expert report as having performed poorly. Yet he continues to practice.”

Though physicians can be board certified in a variety of specialties, primary care or internal medicine expertise is considered critical in correctional settings, where there’s often only one doctor seeing patients with a diverse range of needs, the expert teams concluded. As of 2018, the second expert team determined, only 53 percent of the Wexford physicians working in Illinois had specialized training in primary care, and of those, fewer than a quarter had an advanced board certification in the field.

In early 2016, Sood’s supervisor, Dr. Louis Shicker, had grave concerns after reviewing the death of another one of Sood’s patients. Shicker, then the agency medical director for the IDOC and one of the state employees charged with overseeing the performance of Wexford doctors, classified the case as “a likely avoidable death” and wrote in an email that he had discussed the case at length with the company’s executive-level physicians. “We agree that Dr. Sood has now made some significant errors in the care of IDOC patients at Hill [Correctional Center] and that he will receive a final warning and likely termination or voluntary resignation,” Shicker wrote. Instead, according to emails quoted in court documents in the class action case, Wexford moved Sood to another prison in Illinois. Shicker did not respond to requests for comment or to mailed questions.

Sood did not respond to questions for this story, and Gedman declined to comment on the allegations against him. When the IDOC brings issues about a physician to the company, she said, it attempts to find a “mutually acceptable resolution,” though the company ultimately has final say over any decision. “We’ve transferred some physicians from a more complex facility to a less complex facility if we thought they were better suited for that,” Gedman said.

She questioned the expert team’s assertion that a doctor trained in nuclear radiology or another speciality would be ill-equipped to provide primary care. All doctors get primary care training in medical school, she noted, and said that board certification has little to do with a provider’s performance. Gedman added that the doctors she hires have an average of 29 years experience practicing in general, clinical environments, even if they lack a primary care specialty, and the company provides doctors with refresher courses on primary care. “Frankly, [board certification] doesn’t mean much of anything,” she said. Gedman also provided updated statistics regarding Wexford physicians in Illinois, noting that 52 percent of the company’s regular full-time or part-time doctors are now board certified in primary care or internal medicine. These statistics could not be independently verified.

Image: Illustration by Claire Merchlinksy

The court records include evidence that the IDOC was long aware of problems involving the doctors in its facilities. Another doctor, Vipin Shah, has struggled in his work treating prisoners, according to emails exchanged between his colleagues. In July 2015, staff members at Pinckneyville Correctional Center, a prison where Shah worked, contacted Shicker with urgent concerns about Shah’s performance; Shah had ordered vitamins and observation for a patient with an emergent health condition, and the patient had to be rushed to the ER the next day. “The Nurse Practitioner is getting upset in regards to Doctor Shah,” wrote the health care unit administrator, an IDOC employee. “We need to do something,” the regional coordinator wrote to Shicker in reference to the same event. “Dr. Shah is doing poorly!”

Shah declined an interview request when reached on the phone.

Omar McGhee filed suit against Illinois Department of Corrections employees and Wexford over his medical treatment. In 2015, McGhee, a prisoner at Southwestern Illinois Correctional Center, started experiencing numbness and tingling in his arms. In his legal complaint, McGhee claims that he reported worsening symptoms for months to Bharat Shah, the same doctor who treated Gerry Armbruster the year before. McGhee had two sets of X-rays, the second of which showed what was causing his issues. McGhee says that Shah told him the problem could be fixed with minor surgery, but that it would not be approved until McGhee had completely lost the use of his left arm. The case was dismissed after McGhee failed to show up at a court hearing in September 2016.

Shah denied any wrongdoing in treating McGhee, and in an affidavit suggested he wasn’t present during all the dates of treatment. He did not respond to requests for comment.

It’s not always clear who is ultimately accountable for lapses in prison healthcare. The prison systems hire private companies as contractors, but often can’t fire the doctors that work for them. Though it is contracted by the IDOC to provide care, Wexford was initially named in the class action lawsuit, but later dismissed and not included in the subsequent settlement agreement. Both Vipin Shah and Sood are Wexford employees, and despite the conditions of the settlement agreement, the company still has final say over their discipline or termination.

A spokesperson from the Illinois Department of Corrections declined to respond to a detailed list of questions and stated, “The Department is currently in the process of implementing the recommendations in the Lippert consent decree.”

These problems go far beyond Illinois. In each step of the process, from recruitment to hiring and work performance, corrections agencies struggle to find high-performing physicians. In Louisiana, when reports showed that nearly a third of the prison doctors in the state had a record of misconduct, its corrections agency said “sometimes it’s so desperate a situation, you just need a body in the job” when it came to finding physicians to work in the prisons.

In response, agencies turn to the private sector for help. Corrections is a lucrative industry and some companies, like Wexford Health Sources, specialize in correctional healthcare. Gedman, Wexford’s chief administrative officer, said the company uses myriad recruitment strategies, including text campaigns, networking events, and TV and billboard ads. “We try to recruit—just like any hospital tries to recruit—the absolute best doctors that we could possibly recruit,” said Gedman. Still, she acknowledged the difficulty of recruiting physicians to work in correctional settings, which are often in extremely remote areas. “If you are a physician and you have the natural means to do a lot of things because you make generally a good bit of money, oftentimes [you] don’t want to be in the middle of a corn field in Illinois.” she said.

- Some practitioners with disciplinary histories bounce from state to state.

Private companies, like hospitals, can check the disciplinary records of potential employees, and they also have access to the restricted records of the National Practitioner Data Bank, a resource that contains all disciplinary action taken against a medical provider. In the class action lawsuit in Illinois, a regional coordinator testified that licensing was the only credential the IDOC reviewed before hiring a physician; the details on training, board certification, or disciplinary history were not part of the review.

Gedman said Wexford does check the data bank before hiring a physician. But a mark on a physician’s history is not an automatic disqualifier from a job treating prisoners, she said. If the medical board allowed the doctor to keep a license, the doctor is still a viable candidate, and a credentialing team decides whether the candidate is a good fit. “Sometimes the answer is yes, even though they may have an issue on their license from the past,” Gedman said.

Some practitioners with disciplinary histories bounce from state to state. Dentist Ruthie Jimerson was disciplined by two health boards: the Michigan Department of Community Health in 2008, and the Indiana State Board of Dentistry in 2013. In a 2018 contract, Jimerson is listed as a dentist employed by Centurion, a corrections healthcare company that provides care in Tennessee prisons.

When Douglas Reaves was a patient of Jimerson’s at Wabash Valley Correctional Facility in Indiana, he said she already had a reputation for being rough on patients. He alleged in federal court that she started extractions before numbing medication took effect, broke teeth, and injured prisoners. In 2015, Reaves filed a lawsuit against Jimerson and her supervisor, alleging that she broke a cap off his tooth and, rather than repair the damage, extracted the tooth. According to his suit, Jimerson had been barred by the Indiana state board of dentistry from performing a cap repair without a supervisor present. He eventually settled the case.

Jimerson did not respond to repeated requests for an interview, but in court documents she denied any wrongdoing.

Gerry Armbruster’s case shows the human cost of prison healthcare gone awry. Armbruster grew up in the small town of Granite City, Illinois. He got a job at the local Hardee’s and dropped out of high school in his junior year. His real passion was cars; he was always fixing and repairing them, and drove a tow truck for many years. “I had a pretty good life until I started using drugs,” Armbruster said. “I was addicted to cocaine and started breaking the law, doing stupid things that I regret.”

Gerry as a child (left), with his family.Image: Courtesy of Gerry Armbruster

In 2011, he was arrested for burglary and aggravated battery and sentenced to three years in prison; it would be his fourth time in prison. In the spring of the final year of his sentence, the pain began. “It started with my hands,” Armbruster said. “My fingertips were always numb, my wrist was hurting, my elbows was hurting, I could barely walk.”

When his then 2-year-old daughter would come to visit, Armbruster was too weak to even lift the toddler. “I thought it would go away but it didn’t go away; it kept getting worse,” he said. The numbness, pain, and tingling became more and more disruptive. “Whenever I had to use the restroom, [it] was very difficult,” Armbruster said. “I had to go straight from the toilet right to the shower because I couldn’t move that good to properly cleanse myself. And that’s when I knew it was really bad.”

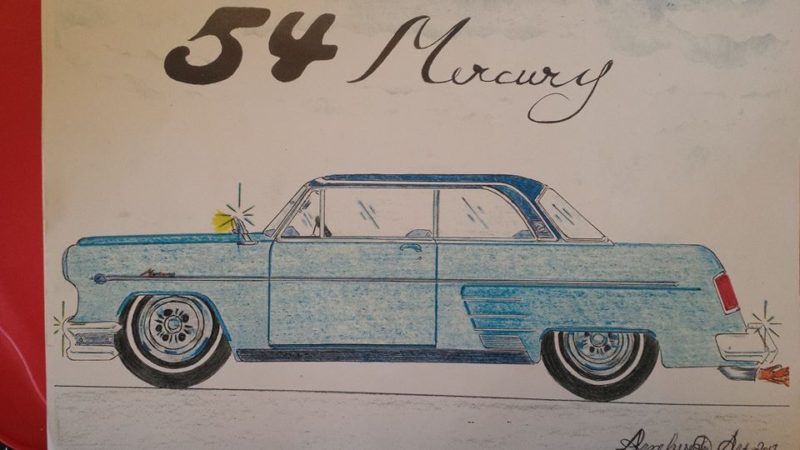

Armbruster once dreamed of drafting cars for Chrysler. In prison he would draw every day, designing cards for fellow prisoners to send home to loved ones. “In prison, everybody’s got a hustle,” Armbruster said. “So that was my niche, I drew for my honey buns and my coffee.” He would charge a few dollars a card and sell about 10 cards a day. “I’d call it, not a Hallmark, but a Jailmark. Jailmark by Armbruster Art, that was my hustle.”

When his hands started to bother him that spring in 2014, his business took a hit. He couldn’t hold a pen or a pencil to draw, he said. “[I] stopped when I couldn’t use my hands no more.”

A picture of a car that Gerry drew while incarceratedImage: Courtesy of Gerry Armbruster

Armbruster filed at least two grievances with prison administration after his symptoms began. In the first, submitted less than a week after he first saw the doctor, he claimed that he was not getting adequate medical attention, and that the doctor only told him to drink more water. The second grievance came just a month after the first. In the second, Armbruster claimed that the medical staff told him Wexford and the IDOC would not fund the expense of sending him to an outside hospital for care. By this point, Armbruster had extreme difficulty writing and needed another prisoner to write the grievance for him.

“I’m in terrible pain, can barely move, have problems with simple task[s], such as getting dressed, taking showers, using [the] restroom, walking, sleeping, arms are continuously numb at all times,” the grievance said. “I’m only requesting proper medical assistance, so I’m able to walk and experience no more pain.”

Gedman disputed Armbruster’s account of his interaction with medical staff and stated that Wexford has never denied care to a prisoner to save money.

Yet, Armbruster’s lengthy struggle illustrates the difficulty prisoners have in seeking redress. Non-incarcerated patients can bring a medical malpractice suit to seek justice and accountability from a doctor who has harmed them. For incarcerated patients, medical malpractice claims can be brought on a state level, but the process is complicated. Requirements can vary, but often state courts require any plaintiff to have an affidavit from another medical professional, attesting that the care the patient received was below professional standards. This second opinion can be near impossible for prisoners to get.

“A prisoner is going to have no chance whatsoever of finding such a doctor who’s willing to talk about other doctors, from his jail cell,” said Alan Mills, executive director of the Uptown People’s Law Center. This challenge weakens one of the few means of accountability available to a prisoner. The arduous process, advocates say, means bad doctors have essentially no consequences for errors and mistreatment, and little incentive to improve.

Derrick Echols, who is serving a life sentence in Illinois, faced all of these hurdles in 2009 after a prison dentist broke a drill bit in his mouth, then stitched the wound with the metal debris still inside. He filed a civil rights case in federal court, and included copies of the X-rays showing the metal pieces in his mouth. Still, the court called his allegations “factually frivolous” and dismissed the lawsuit with prejudice. He successfully appealed the dismissal, and says he eventually settled with his dentist’s insurance company for $22,500 this year.

Given the difficulty of filing state claims, prisoners typically turn to federal court for help, claiming that their civil rights have been violated by the treatment they received in prison clinics.

Apart from the class action suit in Illinois, just under 700 federal prisoner civil rights lawsuits were filed against Trost, Obaisi, Vipin Shah and Sood over the course of the last 25 years. Though the outcome of those cases are unknown and it’s unclear how many of them relate to patient care, advocates say the sheer number of cases filed suggests that the problems were widespread.

Gedman disagreed with the notion that the number of lawsuits reflects quality of care. Incarcerated people are highly litigious, Gedman said. Even if you’re the perfect doctor, “you’re still going to get a lawsuit. That’s just what they do.”

But advocates like Mills point out that such lawsuits are often a prisoner’s only available option. A federal law, the Prison Litigation Reform Act, restricts when, how, and what kind of help a prisoner can get. The law, enacted in 1996, requires a prisoner to exhaust the corrections agency’s grievance system before filing a claim in court alleging negligent care.

Overseen by corrections officials, the grievance process in many states is extremely complex, with tight deadlines and detailed requirements; any misstep risks disqualifying a prisoner from filing a subsequent federal lawsuit. If a prisoner files a lawsuit before exhausting these remedies, the case will be dismissed without prejudice, allowing them to go back and begin the grievance process again. However, the window to file a grievance after the initial incident is often quite short, meaning that many prisoners aren’t able to meet the deadline.

“If you don’t jump through all those hoops properly, in the right order then you are forever barred from bringing your case in federal court,” said Mills, “no matter how good it is.”

A spokesperson for the Illinois Department of Corrections declined to answer specific questions about the agency’s grievance process.

The decisions that doctors made behind the walls of the prison continued to affect Armbruster long after his release in September 2014.

Armbruster waited 10 days for his Medicare card to arrive before going to the doctor for his pain. “The day that came in the mail was the day I went to the emergency room,” he said. “My mom dropped me off, and I walked into the emergency room and I did not walk out.”

Testing done that day showed Armbruster’s spinal cord was squeezed nearly in half, from a healthy 10mm diameter down to 5.5mm. He cried with relief when the doctor told him they had found the source of his pain.

The neurosurgeon operated on Armbruster for about an hour that night. “I woke up and didn’t feel no pain at all. I was like ‘Hmm, hey, it’s over with, it’s gone,” Armbruster said.

“It wasn’t gone.”

The months-long wait for surgery has led to what doctors say is irreversible damage to Armbruster’s spine. He often has trouble walking and deals with near constant numbness and tingling.

“It was better, a lot better, but it was not by far, done,” he said. “It took a long time to get where I am right now.”

The continued symptoms have forced Armbruster to get creative in his daily life. He started keeping spare cell phones around because his phone repeatedly slipped from his numb fingers and broke on the ground. “I always try to keep my mind on something other than the pain,” Armbruster said.

In the first year after his surgery, when his youngest daughter, then 3, would visit his home, he did his best to keep up with her, but found her too quick. He tied a rope around her waist and around his own, so she wouldn’t get too far away when she ran and played.

Armbruster now lives in an RV near his girlfriend’s house in Cottage Hills, Illinois. With few organizations interested in hiring someone with a felony record and physical limitations, finding work has proved near impossible. He relies on the generosity of his friends and family to keep him afloat. Armbruster can’t draw and can’t work on cars but does his best to keep busy.

“There’s nothing I can do. I’ve just accepted that this is the way it is,” he said. “I know it’s not gonna get better.”

This article was reported in partnership with Type Investigations, where Taylor Elizabeth Eldridge is an Ida B. Wells Fellow.