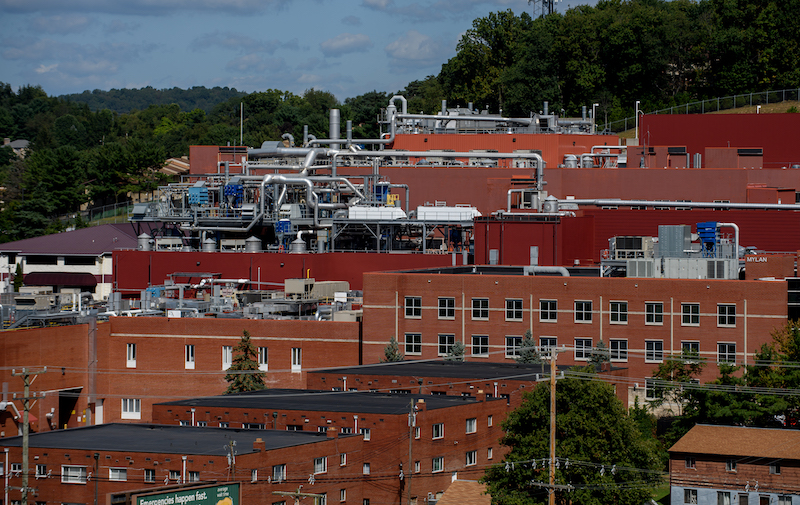

A cacophony of machines, some as big as a dump truck, mix pharmaceutical ingredients, press them into tablets, and fill capsules at a West Virginia factory owned by generic-drug giant Mylan. By the end of each run, the walls, ceilings, floors, and nearly every nook and cranny of the intricate equipment were caked in powdery drug residues, say three former Mylan employees.

No matter how much the machines and floors were swept and vacuumed and wiped down, “there was always powder left on the machines and walls,” said one employee who worked in packaging and other manufacturing roles for nearly five years until being laid off last year. “You see the powder everywhere.”

It was standard practice, the former workers said, to then hose down some of the rooms and machines for up to eight hours and then spray them with alcohol to clear the remaining drug residues, and the wastewater would flow down a drain in the center of each room.

“You just go dump it down the drain,” said the employee who was laid off in 2018. “It always bothered me pouring pharmaceuticals down the drain,” said another former employee who worked in quality control for nearly 10 years. Both requested anonymity because they say they signed nondisclosure agreements.

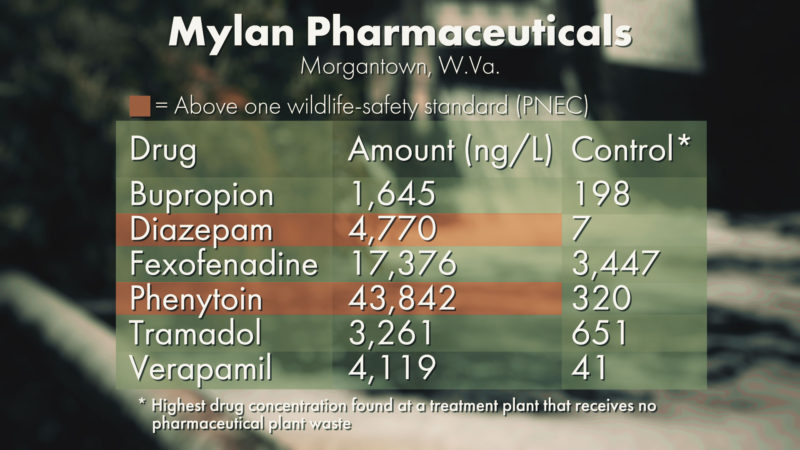

The drug-tainted wastewater streamed through underground pipes to a municipal treatment plant, but some of the medicine likely passed through unhindered and out to the Monongahela River. Typically, wastewater treatment plants are not equipped to remove pharmaceuticals, so when scientists from the United States Geological Survey tested effluent from the Morgantown, W.Va., plant several years ago, along with the discharges from six other treatment plants, it detected very high levels of some drugs. Downstream from the Morgantown plant, an anti-seizure medication was measured at nearly 90 times the amount considered safe for wildlife.

“The drug levels are insanely high. Locally those concentrations would no doubt have an effect on wildlife,” said Tomas Brodin, an expert on the ecological impact of drug pollution who teaches at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Umeå, of the USGS test results.

Over the past decade, cocktails of drugs from opioids to antidepressants have been showing up in rivers all over the U.S. Studies have detected these chemicals in the bodies of fish and aquatic insects, altering behaviors that are key to survival. Now, an investigation by STAT and Type Investigations identifies for the first time major drug companies that are likely dumping substantial quantities of drugs from their manufacturing facilities into rivers and streams.

Until now, consumers have shouldered much of the blame for drug pollution, which can enter the ecosystem through urine or from flushing unused drugs down the drain. Although drug pollution from consumers is widespread, it generally occurs in low concentrations. Contaminants leaking from manufacturing facilities, in contrast, can be found at much higher levels that can be harmful to fish and other aquatic life downstream.

The outflow pipe at the Morgantown Utility Board.Image: Jeff Swensen for STAT News

“The dose makes the poison — it is the concentrations that count,” said Joakim Larsson, an environmental pharmacologist and expert on pharmaceutical manufacturing pollution at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

Mylan and the other companies identified by the investigation would be breaking no federal or state laws by contributing to drug pollution in waterways; pharmaceuticals are not a regulated pollutant in the U.S. Mylan issued a statement disputing the investigation’s findings. The company, it said, is “committed to caring for the environment and promoting responsible manufacturing by taking steps to minimize the environmental impact of our operations and products, while also balancing our need to produce high quality, life-saving medication.”

- ‘Some aquatic insects can have drugs at concentrations thousands of times higher in their body than in the water. They are basically small pills crawling about on the bottom waiting to get eaten by fish.’

The company noted that two hospitals discharge their waste into the same treatment facility as Mylan does, and that Morgantown has a large population — around 60,000 people, including students — making it “unfounded and irresponsible to surmise that Mylan is the likely source of the drugs detected at the Morgantown wastewater treatment facility.”

Hospitals are another significant source of drug pollution and, according to studies in the U.K. and Canada, in some circumstances can release compounds such as injection antibiotics or cancer drugs in concentrations potentially harmful to the environment. But, experts say, drug concentrations from hospitals are generally lower than those leaking out of drug manufacturing facilities, and can be up to 10 times lower. This is partly because when a drug passes through a patient, some of it is metabolized into different compounds, said Dr. Karin Helwig, who studies pharmaceutical pollution at Glasgow Caledonian University in Scotland — though she noted that drug concentrations will vary depending on the size of the hospital and how much water they are diluted with.

Last year, the USGS reported that pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities were discharging substantially elevated amounts of 33 different drugs in their wastewater, after testing levels downstream from the factories. The USGS collected the wastewater from one plant in 2010 and the rest between 2012 and 2014. “We showed that pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities are a significant source of pharmaceutical ingredients into the environment. Wastewater effluents without manufacturing waste had dramatically lower levels of drugs,” said Patrick Phillips, a hydrologist at the USGS and a lead author of the study.

The data in that survey are anonymous, saving the responsible drug companies their blushes and shielding them from pressure to clean up their act.

But by filing Freedom of Information Act requests, searching regulatory databases, and interviewing former drug company employees, STAT and Type Investigations determined that six companies were likely responsible for the high levels of drug pollution detected at seven wastewater plants. In addition to Mylan, they are Pfizer (PFE), based in New York; the Israeli generics manufacturer Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; Watson Pharmaceuticals; Actavis Generics; and Mallinckrodt (MNK) Pharmaceuticals, headquartered in the U.K. (In 2013, Watson acquired Actavis and changed its name to Actavis; in 2016, Actavis was purchased by Teva.)

Another seven treatment plants sampled by the USGS were not included in the investigation because high drug levels were not detected or the nearby drug manufacturing facilities have since closed.

In some cases, the USGS found drugs downstream from the manufacturing facilities at levels thousands of times higher than in rivers that don’t contain manufacturing waste, and at concentrations thought to endanger wildlife. For example, phenytoin, a drug used to treat seizures, was found in the effluent of the wastewater treatment plant in Morgantown at concentrations of 43,842 nanograms per liter, more than 87 times above levels regarded as safe for wildlife, as calculated by academic scientists — a measure known as the predicted no effect concentration (PNEC). In contrast, the highest concentration of phenytoin detected in wastewater not receiving discharges from drug manufacturing plants was just 320 ng/l.

For many drugs, the PNEC is a key indicator of potential danger to the environment. It’s calculated using several thresholds such as the amount of a drug that would kill half a population of small organisms.

PNECs are calculated by both drug companies and academic scientists. Drug companies are encouraged by regulators to test the toxicity of new medicines on wildlife, and in some cases they calculate PNECs for new and older drugs. In some cases, academic and industry scientists calculate different PNEC values for the same drug depending on factors such as the sensitivity of the tests they use.

Some academic scientists warn that PNECs can underestimate a drug’s potential environmental danger because they don’t take account of factors such as how drugs affect the way fish behave in the presence of a predator. Studies also show that some drugs can harm wildlife at concentrations below their PNECs.

“You need to be looking at life history traits such as predator-prey interactions,” said Emma Rosi, an aquatic ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y., explaining that subtle ecological effects on behavior can severely affect animals’ survival and ability to reproduce.

The Morgantown Utility Board Water Treatment facility treats 9-11 million gallons of water per day.Image: Jeff Swensen for STAT News

Drugs have been found in the bodies of fish and water-dwelling insects such as damselflies, and can pass up the food chain when predators, such as spiders and fish, eat contaminated prey.

“Some aquatic insects can have drugs at concentrations thousands of times higher in their body than in the water,” Brodin said. “They are basically small pills crawling about on the bottom waiting to get eaten by fish.”

In a 2015 paper in the journal Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, representatives from 11 leading drug companies acknowledged that drugs can be released from manufacturing facilities and result in “hot spots” of pollution. But the paper maintains that manufacturing contributes less to the overall drug pollution problem than do consumers. “The primary pathway is through normal patient use,” it says.

An industry group has calculated that manufacturing contributes a small fraction — around 2% — to overall drug pollution, though academic experts and environmental consultants question the validity of this estimate.

The 2015 paper points out that some companies are taking steps to reduce drug discharges from manufacturing, such as installing wastewater treatment facilities onsite to clean discharges before they are sent to municipal sewage treatment plants, and sweeping and vacuuming drug residues before machinery is washed.

Drug companies from around the world have formed a coalition to tackle the rise of antimicrobial resistance by cutting down on releases of antibiotics from manufacturing facilities. But the pharmaceutical industry has made no such commitment to clean up pollution from other drugs.

The drug pollution downstream from Mylan’s plant was among the highest detected by Phillips and his USGS team, which sampled the effluent coming out of 20 wastewater treatment plants in nine states and Puerto Rico. Thirteen of the plants received wastewater from pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities, while six did not treat pharmaceutical wastewater and were used as a comparison. At the final treatment plant, the USGS sampled the plant while it was receiving drug-manufacturing wastewater, and after production stopped.

STAT and Type Investigations identified the companies likely responsible for the pollution through a laborious process: First, information was obtained through the FOIA giving the locations of the treatment plants sampled by USGS. A reporter then confirmed with those treatment plants which drug companies had permits to discharge wastewater into them; in most cases, just one drug manufacturer discharged into each plant. Finally, the reporter determined some of the drugs made at each manufacturing facility to check whether they matched medications detected at high concentrations in wastewater.

Mylan, which earned $11.43 billion in 2018 and has announced a planned merger with Pfizer’s generic and off-patent drug division, is no stranger to controversy. It has faced intense criticism over a 400% increase in the price of its EpiPen, used to treat life-threatening allergic reactions, between 2010 and 2016. And over the past 20 years, it has reached settlements with the federal government over a string of allegations, ranging from price fixing to false claims, and has racked up nearly $1 billion in fines.

It’s also been cited for violations at its West Virginia factory. Last year, the Food and Drug Administration reprimanded the company after an inspection found major lapses in equipment cleaning and poor laboratory and quality controls at its Morgantown facility. In the Nov. 9, 2018, warning letter, the FDA noted that it had previously cited Mylan for similar violations at the Morgantown plant and others and added: “These repeated failures at multiple sites demonstrate that Mylan’s management oversight and control over the manufacture of drugs is inadequate.”

In a statement at the time, Mylan said it has “implemented a comprehensive restructuring and remediation plan” and “will continue to work to ensure that the [FDA] is satisfied with the steps we have taken to resolve all the points raised in the Warning Letter.”

The Morgantown facility is situated close to the Monongahela River, known as the “Shit Mon” by locals because, as one former employee said, stretches of the river “smell so bad you can’t go near it.” Several other industries operate in the area, including coal mining and natural gas production.

Image: ALEX HOGAN/STAT

In the effluent from the Morgantown wastewater plant, the USGS team found high concentrations of three drugs in addition to phenytoin. The detected concentrations of fexofenadine, an antihistamine; diazepam (Valium), used to treat anxiety; and verapamil, a blood pressure medication, ranged from five to 707 times higher than in effluent with no drug manufacturing pollution.

The diazepam concentration was less than one-fifth of the drug’s PNEC calculated by industry scientists using real-world experimental data, but it’s over twice as high as an alternative PNEC calculated by academic scientists using a theoretical model that is more conservative. For some drugs, such as fexofenadine and verapamil, the PNECs are unknown because the calculations have not been done or are not publicly available.

Information released by the FDA confirms that Mylan is the only drug company in the area that produces the drugs detected at high levels. While some of these drugs could have come from two nearby hospitals, academic experts interviewed for this story said the concentrations detected in the Morgantown wastewater are unlikely to have come from the hospitals alone.

Helwig, of Glasgow Caledonian University, said the concentrations at the Morgantown site are “quite high” and it is likely that there is “another significant effluent present in the mix” beyond what is discharged by the hospitals.

In a letter to the Morgantown Utility Board, which operates the city wastewater plant, Mylan said it uses “drain plugs in all pharmaceutical processing rooms” — more than 250 of them — to “keep solid material from entering the drains during processing.”

“Drain plugs are installed prior to the introduction of raw materials into processing rooms and are not removed until dry cleaning of the rooms and equipment is completed,” the Oct. 15 letter said. Workers then hose down the rooms and machinery. The letter didn’t specify when the use of plugs began, but Mylan said in a statement that it “began installing plugs in 2010 and expanded them to all manufacturing rooms by 2013.”

The three former Mylan workers said they didn’t observe the drain plugs used as Mylan described when they worked at the plant as recently as last year. Two said they had never seen the plugs being used in the production rooms. Instead, they said, the drains were covered with grates with holes that were meant to stop large objects from falling down the drain.

“It wasn’t really there to catch drug product,” said the employee who worked at Mylan for nearly 10 years until leaving in 2017. The dry cleaning, which included sweeping and vacuuming is “very quick,” he added. “I would guess it gets 60% of the dust. Even with the best vacuum in the world, some drug product would still be left,” the former employee said.

The Mylan Laboratories pharmaceutical factory in Morgantown, West Virginia.Image: Jeff Swensen for STAT News

Another employee who worked at Mylan for about five years, until 2018, said the plugs “might have saved some drugs but no plug stopped everything. If you pick up the drain cover you can see drug powder on the underside.”

A third employee who worked there from 2010 to 2014 said drains in some rooms were blocked off with plugs but most were not.

The drug discharges do not put Mylan in violation of any state or federal law, and the company said it “has a very strong record of compliance.” The Morgantown Utility Board confirmed that the company is in full compliance with its federal and state requirements for the quality of its wastewater, though the rules do not require monitoring or testing for pharmaceutical products. The technologies used at the Morgantown wastewater treatment plant are undergoing upgrades that should help eliminate more pharmaceuticals from the effluent.

High levels of drug pollution were also found downstream from a manufacturing site operated by the global drug giant Pfizer, in the industrial heart of north central Puerto Rico. In effluent from a treatment plant in Barceloneta that receives wastewater from the Pfizer facility, the USGS detected celecoxib, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug used to relieve pain, at almost 15 times the environmentally safe levels as calculated by industry scientists. The USGS measured fluconazole, a fungicide, at over 2,000 times the levels safe for wildlife as calculated by academic scientists. Respectively, the drug concentrations were 228 and 3,171 times higher than detected in effluent not receiving drug-manufacturing waste.

Image: ALEX HOGAN/STAT

Hospitals discharge into the Barceloneta treatment plant, as do several other drug companies. But information from the FDA and the other companies confirms that Pfizer is the only manufacturer in the area that produced either drug when the USGS tested the wastewater. Sally Beatty, a spokeswoman for Pfizer, confirmed that the company currently makes products that contain celecoxib and fluconazole there.

The fluconazole found downstream from the Pfizer facility was at the highest concentration detected at any site in the USGS study. Three former employees with knowledge of Pfizer’s Puerto Rico operations — they asked for anonymity because they were not authorized to talk — said the company maintains good environmental and safety procedures and even cleans its wastewater on site. However, technologies often used in wastewater treatment don’t effectively remove many pharmaceuticals.

Over the past five years, Pfizer and its subsidiaries have been hit with over $500,000 in federal and state fines for environmental violations, including breaches of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act by the Barceloneta plant in 2018. At least seven other Pfizer sites around the country and in Puerto Rico have violated environmental regulations over the past five years, where government action was typically taken, such as issuing the company a notice of the violation.

In a statement, Pfizer said it “cannot be certain of the accuracy, validity, and significance” of the USGS study results and that it is “important to consider whether there were other contributors” of pharmaceuticals to the environment. Pfizer said it “is committed to responsible manufacturing practices that minimize the potential environmental impact.”

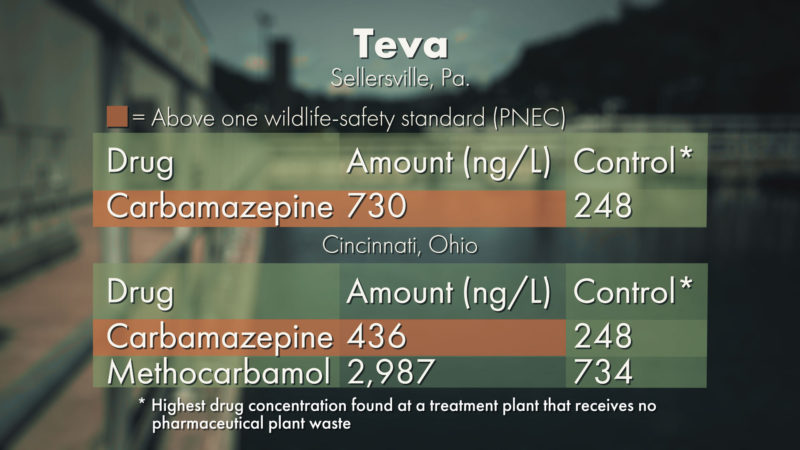

Overall, at four out of seven wastewater treatment plants included in the investigation, at least one drug was detected above its predicted no effect concentration. In addition to the drugs found at Barceloneta and Morgantown, the USGS detected carbamazepine, used to control seizures, at wastewater facilities in Sellersville, Pa., at 1.7 times above levels safe for wildlife, and in Cincinnati, Ohio, at just over safe levels, as calculated by academic scientists.

Image: ALEX HOGAN/STAT

His research is one of a few studies to directly examine the impact of drug pollution from a manufacturing facility in the U.S. It was conducted in part using effluent from the Hobart treatment facility. Schoenfuss also found that the effluent made adult fish develop smaller livers, potentially making it more difficult for them to clear toxins from their bodies, and it caused fish larvae to grow shorter and take longer to escape predators. The results show that harm to animals can be caused by drug pollution at concentrations found in the environment.

Mallinckrodt said it had no comment on the findings.

Altering animal behavior can affect the long-term survival of fish populations, scientists warn. “It’s the difference between reproducing or not; even life and death,” Brodin said. “All it takes is a little bit of misbehavior and you are done for.”

Larsson, at the University of Gothenburg, said regulators must pay closer attention to industrial drug leaks. “There is an urgent need for greater transparency and control over emissions from manufacturing,” he said.

In March, the European Union called on industry to improve manufacturing methods to tackle pharmaceuticals in the environment, but the U.S. hasn’t taken similar action. A handful of states, most recently New York, have established programs financed by the drug industry to take back and safely dispose of unused drugs. And in August, the Environmental Protection Agency prohibited health care facilities from flushing down the drain pharmaceuticals regarded as hazardous waste, such as chemotherapy drugs. These initiatives can help curb drug pollution more generally, but not releases from manufacturing plants.

“The effects [of drug pollution] are fairly local at the moment, but if we don’t clean, it will build up to higher and higher levels, especially really persistent drugs,” said Brodin. “It will just keep adding up.”

This article was reported in partnership with Type Investigations, a nonprofit newsroom.