At a casino in the small coastal town of North Bend, Oregon, dozens of law enforcement officers and corporate security personnel gathered for a two-day training on how to wage propaganda battles against protesters. The November 2018 event was organized by the National Sheriffs’ Association, one of the country’s largest law enforcement organizations, and hosted by the Coos County Sheriff’s Office, which has spent years monitoring opposition to the Jordan Cove Energy Project — a proposed liquid natural gas pipeline and export terminal that the Trump administration has named one of its highest-priority infrastructure projects.

The cost of the event, however — totaling $26,250 — was paid by Pembina Pipeline Corp., the Canadian fossil fuel company that owns the Jordan Cove project.

In fact, for nearly four years, Pembina was the sole funding source of a unit in the sheriff’s office dedicated to handling security concerns related to Jordan Cove — despite the fact that there is not yet any physical infrastructure in place to keep secure. The pipeline and terminal cannot begin construction without approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which is scheduled to vote on whether to license the project in February. Yet between 2016 and 2020, the department’s liquid natural gas division, known as a “combined services unit,” spent at least $2 million of Pembina’s money. The energy company put the funding on hold in April 2019 but left open the possibility that the arrangement could be revived in the future. Pembina and the sheriff’s department are currently discussing how they may continue to work together, and Coos County Sheriff Craig Zanni said he expects the partnership to be renewed.

In addition to hosting the law enforcement training, the unit used Pembina’s funds to purchase riot control equipment, monitor the activities of Jordan Cove opponents, and coordinate intelligence-gathering operations with private security companies that also worked for Pembina. Local residents, environmental activists, and tribal members have staged rallies and sit-ins and participated in public hearings in opposition to the project, which they say would exacerbate the global climate crisis, damage vital waterways, and violate Indigenous sovereignty. Dozens of property owners could see their land seized via eminent domain.

Law enforcement agencies often receive funding for equipment via corporate-backed professional associations and private foundations — a practice that civil liberties groups have criticized as enabling private influence with little oversight. The arrangement between Pembina and the Coos County Sheriff’s Office was unusual, however, given the department’s scrutiny of activists engaged in First Amendment-protected speech in opposition to its corporate benefactor.

“It’s stunning. It’s the complete opposite of how the police have presented themselves in recent history — that they are neutral parties positioned above the political fray,” said Jeff Monaghan, a criminology professor at Canada’s Carleton University who studies police surveillance. “This is a public police force that has essentially opened up a private, corporately funded wing and, in doing so, is entrenching itself on one side of a very complicated political debate.”

The Coos County partnership is an extreme example of a trend in policing that has gained momentum across the United States — particularly since thousands of protesters from around the world gathered at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota in 2016 and 2017 in an effort to halt construction of the Dakota Access pipeline. Corporations are developing creative means to funnel millions of dollars to local law enforcement groups, and this funding has often been paired with increasingly elaborate private security and propaganda operations.

An investigation by The Intercept and Type Investigations, based on more than 15,000 pages of documents obtained via open records requests from the Coos County Sheriff’s Office and the city of Portland, sheds light on the fusion of public and private interests working to monitor and stymie opposition to the Jordan Cove Energy Project. The documents also reveal new details about a network of private actors profiting off the suppression of protest movements nationwide, among them veterans of the Dakota Access pipeline campaign who have since contributed to the policing efforts around Jordan Cove.

The global consulting firm Teneo led Jordan Cove-related communications and intelligence operations on behalf of Pembina, producing regular reports on the activities of opponents and helping coordinate the efforts of federal, state, and local law enforcement, including the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and county sheriff’s offices, the records show.

At the November 2018 training paid for by Pembina, one workshop was led by employees of Delve, a Washington, D.C.-based opposition research firm affiliated with the national Republican Party that worked alongside police during the Dakota Access pipeline protests.

Another was led by former consultants for TigerSwan, the defense firm hired to oversee security of the Dakota Access pipeline that came under fire for its militaristic approach to protesters. The two former consultants enlisted to train Oregon law enforcement had previously attempted to organize pro-pipeline counterprotests, according to leaked audio recordings, encouraging dangerous tactics and at one point dangling the prospect of anonymous donations from oil companies.

“Pembina and other corporations are trying to build out the infrastructure now to lock us, as a planet, into using big reserves of fossil fuel,” said Brendan McQuade, assistant professor of criminology at the University of Southern Maine and author of a recently released book on police fusion centers. “The most distressing element of these documents is that they show the police both locally and nationally lining up, in a rigid way, behind corporations carrying out fossil fuel extraction.”

Purchasing Police Power

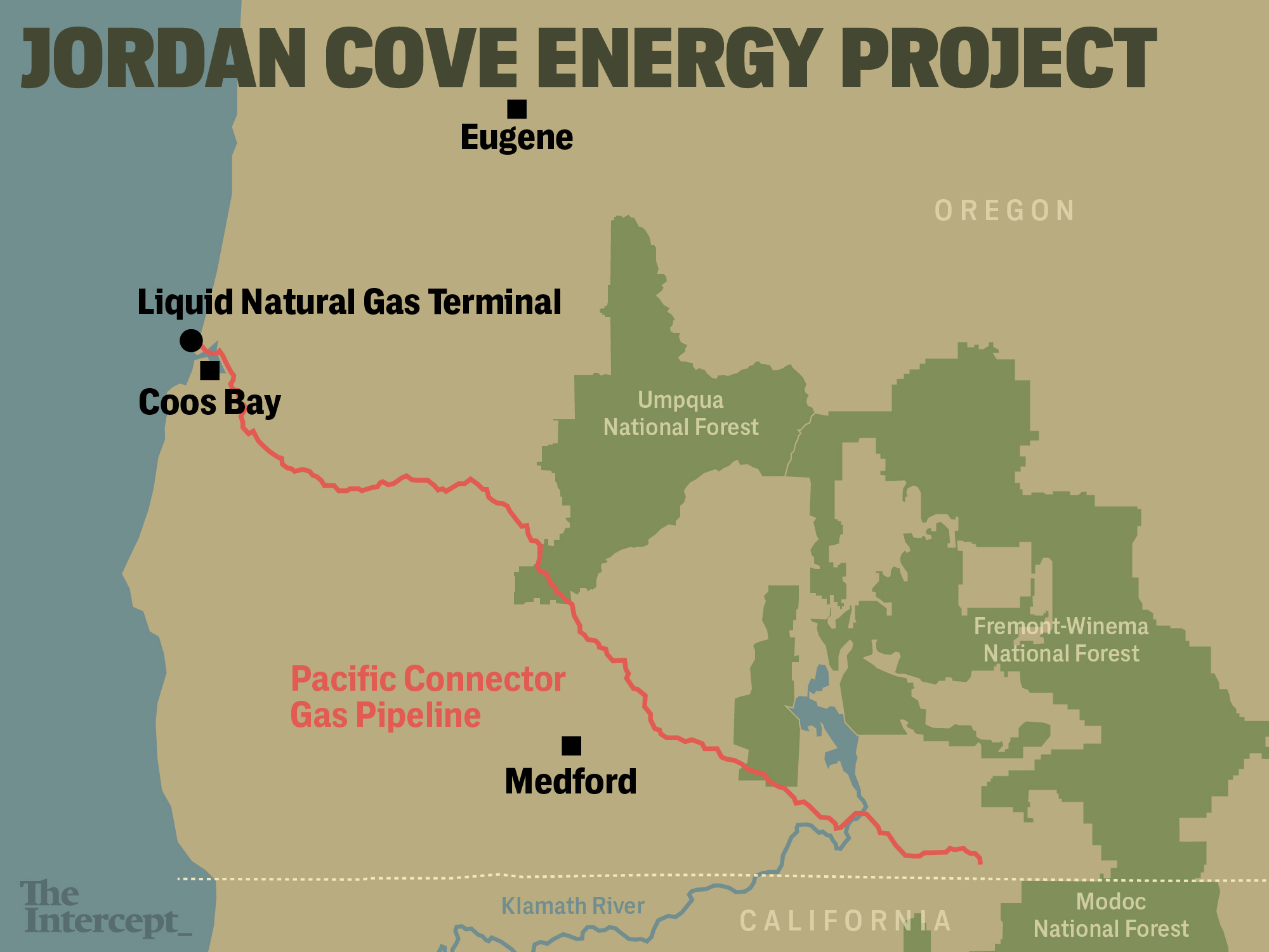

First proposed in 2005, the Jordan Cove Energy Project has become one of the longest-running battles in the country between the fossil fuel industry and opponents of new hydrocarbon energy infrastructure. If built, the project would transport 438 billion cubic feet of natural gas per year from the Jonah Field in Wyoming, the Piceance Basin in Colorado, and the Uinta Basin in northern Utah. The 233-mile Pacific Connector gas pipeline would snake beneath five major rivers as it pumps natural gas to a new export terminal at Coos Bay, where the gas would be chilled and liquefied before being carried to Asian markets on massive tankers.

Image: Soohee Cho/The Intercept

In 2016, landowners in the pipeline’s proposed path successfully lobbied the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which provides permits for the construction of natural gas infrastructure, to deny an application to build the project. The agency asserted that developers had not proven the need for it. Pembina reapplied a year later, in the wake of Donald Trump’s election.Since then, Trump has appointed individuals to the five-member commission who are more in favor of fossil fuel projects than their predecessors, including Neil Chatterjee, who previously served as energy policy adviser to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. A decision by the FERC is expected on February 13.

In the meantime, grassroots environmental groups have helped rally tens of thousands of people to submit comments opposing Jordan Cove to state and federal permitting agencies. The Karuk, Yurok, Klamath, Tolowa Dee-ni’, Siletz, and Round Valley tribes have all passed resolutions opposing the project.

On a misty morning in August, Larry Maghan, a retired Bureau of Land Management biologist, stood on the shores of Coos Bay overlooking the proposed site of the Jordan Cove export terminal. The land on which he and his wife, Sylvia, have lived for more than 30 years is in one of the proposed paths of the Pacific Connector pipeline, and a portion of it is threatened with eminent domain.

“This project would be a disaster not just for us, but for our entire area,” Maghan said. “It’s almost unthinkable that our local police force would be so invested in it.”

The LNG division of the Coos County Sheriff’s Office was established in December 2015. At the time, the Jordan Cove project was owned by the energy infrastructure company Veresen, which Pembina acquired in 2017. Coos County Sheriff Zanni said the department expected Jordan Cove to create an array of security needs. Coos Bay is popular with anglers, crabbers, and recreational boaters who would share the space with giant LNG carriers, and he believed the terminal could become a target for terrorism.

According to county expenditure records, the Pembina-funded sheriff’s unit spent at least $1.2 million on salaries, benefits, and overtime between 2016 and 2020. The sheriff’s office also used money from Pembina to acquire equipment and technology that would allow deputies to monitor environmental activists and respond forcefully to potential protests. Last year, the department spent $48,250 of Pembina funds on an acoustic sound cannon and paid for repairs to a Mine-Resistant Ambush-Protected tactical vehicle — a type of armored vehicle first developed for the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan that police have also used in the streets of Ferguson and at Standing Rock. The department also purchased social media archiving software and a drone.

The sound cannon was a response to what happened at Standing Rock, according to Zanni, who said he wanted a “more humane way” to deal with protesters that would avoid physical confrontation. As for the MRAP, the armored vehicle the department had obtained via the federal government’s surplus military property program was in a state of disrepair. Zanni said the vehicle had “technically nothing” to do with Jordan Cove. “It’s called leveraging for the better of the community,” he added.

Zanni described the sheriff’s office as “severely underfunded.” The department used to rely on proceeds from timber harvests on federal land to pay its bills, but that funding dropped dramatically in recent decades.

When Pembina discontinued funding in April, the sheriff’s office had enough remaining money for the unit to finish out the year. In December, the department was forced to absorb four deputies whose salaries had been paid for by the company (a fifth deputy retired). Pembina did not respond to requests for comment, but a spokesperson for the company told local press that it had adjusted its spending while awaiting permits to build.

The sheriff’s department met with the company in January to review the unit’s expenses and discuss a future agreement. A follow-up meeting has been scheduled for the coming weeks. “We’re going to move forward, basically,” Zanni said.

He pointed to the 2005 Energy Policy Act as justification for the unit. The federal law requires fossil fuel companies to come up with a cost-sharing plan with public agencies that have “responsibility for security and safety” at LNG export terminal sites. Zanni shrugged off the fact that the export terminal has not been approved or built yet. “As businesspeople, they’re pretty confident they’re going to get permission to do that,” he said of Pembina. “My argument is I need the resources before it’s going to be built.”

But, if the agreement is renewed, it may be invalid under Oregon law. In 1998, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against a similar arrangement in Klamath County, Oregon, where the sheriff’s department had entered into an agreement with the timber corporation Weyerhaeuser to provide security services on the company’s land.

“Providing specialized law enforcement services to Weyerhaeuser has no logical relationship to a sheriff’s statutory responsibility to ‘Defend the county against those who, by riot or otherwise, endanger the public peace or safety,’” the court ruled. “We are persuaded that a sheriff lacks the express or implied authority under Oregon law to enter into an agreement to provide security services for private entities.”

“The court was pretty clear in saying that Oregon law sets out the general authority for governing bodies, and these types of contracts between corporations and police agencies don’t fit into that general authority,” said Kelly Simon, a staff attorney at the Oregon chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. “Contracts like this that are biased and create special-interest groups in government bodies — they are not authorized because the police’s authority is to protect the public fairly and equally.”

Zanni said the Coos County Sheriff’s Office has had contracts with federal agencies like the Bureau of Land Management as well as private timberland owners that occupy areas that the office otherwise wouldn’t have the resources to patrol. “Our contracts specifically say if there’s a law enforcement public safety need for that officer, we don’t care what you’re paying us for, he’s going to go handle that,” Zanni said.

Image: Alex Petrowsky for The Intercept

Public-Private Surveillance

Given that the Jordan Cove pipeline and export terminal haven’t been approved or built yet, the Pembina-funded unit of the Coos County Sheriff’s Office spent a considerable portion of its time and resources monitoring opponents of the energy project, according to email exchanges between law enforcement officers and Pembina employees.

Coos County Sheriff’s Deputy Bryan Valencia, whose work was funded by Pembina, operated the email list of the Southwestern Oregon Joint Task Force, an intelligence-sharing group that included officers from the FBI and Bureau of Land Management, as well as state and local law enforcement. The task force, which was set up to monitor “the extremist agenda in southern Oregon,” according to Zanni, circulated posts from activists’ social media accounts and campaign emails sent by grassroots environmental groups such as Southern Oregon Rising Tide, Rogue Climate, and 350 Eugene.

In January 2019, Valencia distributed information to the email list about pipeline opponents who had indicated on Facebook that they would attend a demonstration and permitting hearing in North Bend.

“As of this afternoon there are 98 people RSVP’d to attend the rally and Department of State Lands Meeting,” Valencia wrote. “There are another 384 showing ‘interested.’ Most of the names are recognized as residents spread across the other three pipeline counties. There are a few recognized local names associated with previous rallies.”

“There is no criminal nexus at this time,” Valencia acknowledged.

Indeed, the heightened law enforcement scrutiny occurred even though project opponents have mostly refrained from disruptive protests in favor of lobbying, public comment hearings, and peaceful demonstrations.

The most dramatic action came on November 21, when dozens of people occupied Oregon Gov. Kate Brown’s office in Salem, demanding that she make a statement opposing Jordan Cove. Brown spoke to the protesters but declined to issue a statement. “I’m not putting my finger on the scale one way or another,” Brown said. After more than nine hours, state police arrested 21 people, but the district attorney declined to file any charges.

Jordan Cove opponents said the surveillance was disturbing but unsurprising. “This should clarify for anyone who still doubts which side the cops are really on and who they are invested in serving,” said Holly Mills of Southern Oregon Rising Tide.

“We want to know what’s going on, what’s being planned, and if there’s potential for someone to jump in and create a problem,” Zanni responded. “There are radicals on the protest side; there are also radicals on the other side. Extremists of any sort are dangerous.” As an example, he pointed to protests and counterprotests 200 miles away in Portland involving left-wing anti-fascists and the right-wing hate group the Proud Boys.

Overall, however, he acknowledged that extremists are “not a big element of Jordan Cove’s opposition” and underlined that he is not for or against the project.

But whether or not Zanni took a side, the Pembina funding supported surveillance of pipeline opponents. Valencia spent about 10 percent of his time monitoring social media while he was part of the LNG unit, Zanni said. After the Pembina funds ran dry, the deputy was transferred to the corrections division and his intelligence-gathering ceased along with the department’s work with the extremism task force.

Throughout its collaboration with Pembina, the Coos County Sheriff’s Office was also receiving a steady stream of intelligence from Teneo. The security and public relations firm founded by former aides to Bill and Hillary Clinton helped orchestrate public relations for Pembina while also employing its “risk advisory” division — led by former New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton — to keep tabs on Jordan Cove opponents, according to emails, intelligence reports, and notes from agency planning meetings.

Teneo personnel provided daily and weekly reports to Pembina on pipeline opponents’ activities, which the energy company’s in-house security officer routinely shared with the sheriff’s office. A January 2019 intelligence report, for example, featured screenshots of activists’ social media feeds and cited a “flood” of letters to the editor and op-eds opposing the project. “These compelling storylines will facilitate local groups’ fundraising and outreach efforts to national groups, bolstering the resources at their disposal while also risking the inclusion of national groups willing to pursue more dangerous tactics that would threaten JCP and Pembina,” the memo stated, encouraging “active communication efforts to counter their narrative.

Teneo representatives also met directly with members of the sheriff’s office “to compare notes on monitoring activists” and informed the department that they would begin having “eyes on the ground” at local events pertaining to Jordan Cove.

The company appears to have become integrated into law enforcement operations. In February 2019, Teneo helped organize a meeting featuring representatives of the National Sheriffs’ Association, the Oregon State Sheriffs’ Association, and local sheriffs from counties the pipeline would pass through to coordinate their operations. The next month, at a multiagency planning meeting regarding Jordan Cove organized by the FBI’s Portland division, Teneo delivered an intelligence briefing to the officers and agents in the audience.

“It’s become very normal for private corporations to be on the same team as law enforcement entities and feeding information,” Carleton University’s Jeff Monaghan said. “But in this case, the private entity is actually the one coordinating the fusion of different law enforcement entities. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

In one instance, Teneo Managing Director Jonathan Wackrow asked Coos County Staff Sgt. Doug Strain to classify information the sheriff’s office gathered related to Jordan Cove as “protected critical infrastructure information” by sharing it with the Department of Homeland Security and the Oregon TITAN Fusion Center — part of a national counterterrorism intelligence-sharing network. Doing so would prevent public disclosure of the sheriff’s intelligence-gathering activities based on the 2002 Homeland Security Act, Wackrow wrote.

“We need to formalize this information and ensure that all of the information is labeled as [protected information],” wrote Wackrow, who is also a frequent law enforcement commentator on CNN.

Monaghan expressed alarm that a statute passed in the wake of September 11, ostensibly to protect U.S. infrastructure against attacks by groups like Al Qaeda, would be repurposed this way. “The utilization of that statute is being directed by a private corporation working for a resource company, which is actively directing surveillance activities of a public police agency,” he said. “Clearly, this is not about terrorism, it’s not about national security — it’s about domestic policing.”

- ‘It’s become very normal for private corporations to be on the same team as law enforcement entities and feeding information. But in this case, the private entity is actually the one coordinating the fusion of different law enforcement entities. I’ve never seen anything like it.’

According to Zanni, Teneo overstepped its role, and the sheriff’s office eventually stopped working with the security firm. He said Teneo attempted to direct the department’s activities. “They wanted us to be subservient to them and they were going to show us how to do security for them,” he said. “Not in my county.”

Teneo did not respond to requests for comment.