M. was midway through her 12-hour shift in late March, sorting financial documents in a cavernous Long Island warehouse, when a supervisor stopped by and handed her a flyer. Several days earlier, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo had signed an executive order shutting down most businesses, but M.’s warehouse had remained open because its purpose — mailing and shipping — was defined as essential.

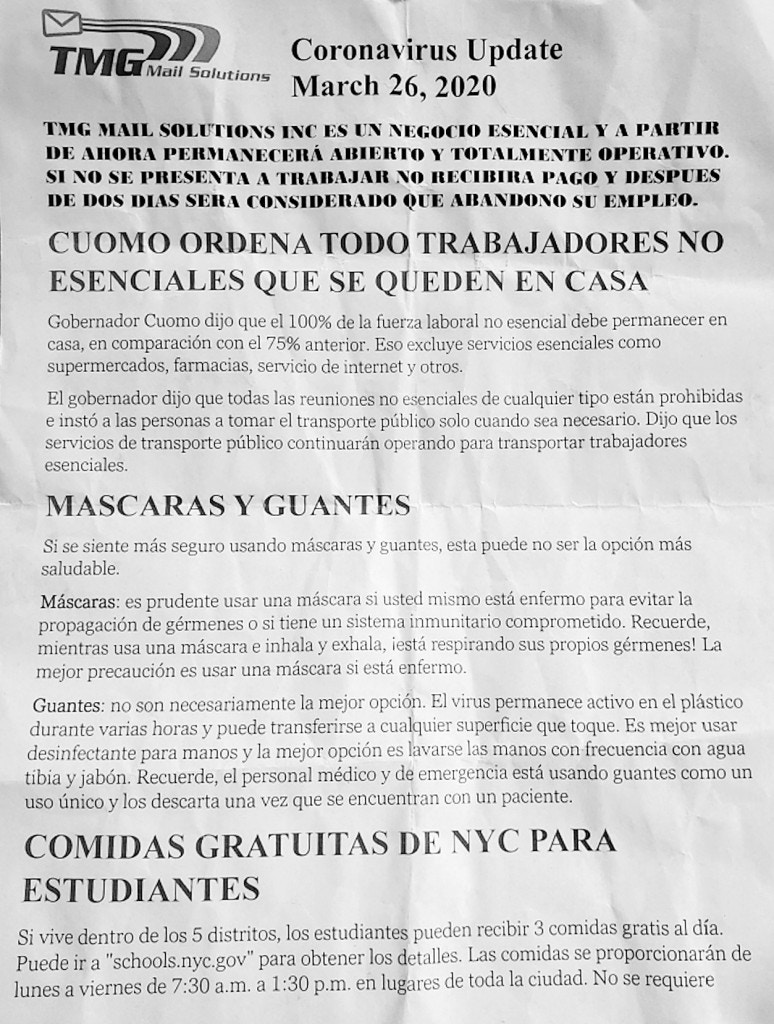

The flyer, written in Spanish, discouraged workers at TMG Mail Solutions, a mailing and printing contractor for businesses, from wearing gloves and masks unless they were sick or had compromised immune systems. In bold letters, the notice also warned, “If you don’t show up for work you will not be paid and after two days you will be considered to have abandoned your job.”

So the next morning, when M. woke up with a slight fever, she went to work, putting in another 12-hour shift without wearing a mask or gloves. She said that the company had not instituted any social distancing measures, and that she ate her lunch in a crowded cafeteria, sharing a table with approximately 10 other coworkers. Within a week, she would go to the hospital and, a few days after that, be diagnosed with Covid-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus strain that has brought the world — but not M.’s warehouse — to a grinding halt.

The warehouse is leased by Broadridge Financial Solutions, a global financial services company with almost $4.4 billion in revenue last year, that employs thousands worldwide. But even as Broadridge was taking precautions to protect its own employees in the warehouse, its vendor, TMG, was taking a hardline approach that endangered its workforce. Not only were TMG workers discouraged from staying home when ill or protecting themselves, according to several employees, they also weren’t notified when their colleagues got sick.

The coronavirus crisis arrived at one of the busiest times of year for the mail and shipping warehouse — with long, grueling hours for employees. Type Investigations and The Intercept interviewed 14 current and former workers at TMG, nearly all of whom shared the same sentiment: They were scared to push back against the company because they needed their jobs.

“What can we do?” one worker said. “We are intimidated. We are afraid to be out of work. We have to pay rent, so we have to keep going.”

The Intercept and Type are not identifying the current TMG workers interviewed for this story by name because they fear retaliation.

A Broadridge spokesperson, Gregg Rosenberg, said that the company had been informed that TMG employees had tested positive for Covid-19, and that Broadridge had “mapped their contacts and notified any of its employees that were in direct contact with instructions to self-quarantine.” He said TMG is expected to notify its own employees.

TMG did not answer questions regarding whether any of its employees had tested positive and, if so, whether it had notified other workers. Another worker told The Intercept and Type Investigations that they were told to quarantine by a supervisor, but that when TMG was presented with a doctor’s note to the office, remarks by a supervisor at TMG suggested the worker’s job was in jeopardy. James T. Prusinowski, a lawyer representing TMG, did not respond to that specific allegation. He said the company “categorically denies any allegations or inferences that it did not take the necessary and appropriate actions or follow CDC guidelines concerning its employees related to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Among the services Broadridge offers is investor communications, which includes the printing and shipping of financial documents — quarterly reports, proxy statements — from the Brentwood, New York, warehouse. Many of the people who do this work are Latina immigrants like M., who earn $13 an hour as employees of TMG, whose office is next to the warehouse and whose partnership with Broadridge goes back decades.

Workers have long shifts year-round, several employees said, but especially during the period from March to May they call “el proxy” — when proxy statements, government-mandated informational documents for shareholders of publicly traded companies, are printed and mailed. Workers said that, during el proxy, shifts can last up to 14 hours and some could go months without a single day off. One former employee said that during the five months she worked for the company last year, three people fainted while on the line. (TMG declined to address that allegation, and Broadridge said it was unaware of it.)

On Tuesday, the law firm of Getman, Sweeney & Dunn filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court against TMG and Broadridge, on behalf of the estimated 200 TMG employees at the warehouse, alleging that TMG failed to properly compensate employees for nonstandard work hours and overtime, as required by New York labor law. (A lawyer for TMG said the company adheres to all labor laws. Broadridge representative Rosenberg said “the company was unaware of such allegations and would refer you to TMG who pays their employees directly.” Neither company responded immediately to requests for comment after the lawsuit was filed.)

The day after she awoke with a slight fever and went to work anyway, M. felt warmer, but she again went in, determined to make it through another shift. She was again not provided a mask or gloves, and said that the company still hadn’t taken any social distancing measures. She spent her lunch break at a full table.

“I kept working because they said if we didn’t keep working, we would be fired.” she said. But, by the afternoon, M. could barely stand. Her body was burning up. She told her supervisor that she would have to miss work.

At home, she collapsed on her bed, where she spent the next four days battling a fever and body aches. She was coughing up blood. Soon, her mother and husband were suffering symptoms as well. A week after she’d received the flyer, M. and her mother went to a local hospital to be tested for the coronavirus. M. shared a letter from the hospital stating that she needed to be excused from work. Four days after her visit, the hospital called to tell her that they both had contracted Covid-19. M. said she subsequently called TMG and notified them of the results. M. fears she won’t be allowed to return to her job when she fully recovers.

The flyer from TMG.Image: Provided to Type and The Intercept

Prusinowski, the attorney representing TMG, did not respond specifically to questions about the flyer, but wrote that the company “has not altered or amended its policies and procedures to the detriment of its employees during this current health and economic crisis.” He also said that the company “has and continues to comply with all applicable labor laws including those relating to hours and days of work and safety protocols.”

Rosenberg, of Broadridge, said that the company works with multiple vendors and had requested that all of them provide sick and quarantine pay for employees, as Broadridge does, and that he was not aware of the policy outlined in the flyer warning workers that they could lose their jobs if they missed two days of work.

As M. wrestled with her illness, rumors of a Covid-19 outbreak circulated among TMG workers, fed by the latest absences. “All of us are talking about coronavirus,” said K., a TMG employee. “All of us are scared.”

With cases of the coronavirus mounting across the country, K. decided to do her own research, and discovered that two of her coworkers — not including M. — had indeed contracted Covid-19. When reached by The Intercept and Type Investigations, both workers said that they had the disease and that they had shared their test results by phone with TMG. One worker could only speak several words in a row before pausing and gasping for air.

Another said that they had alerted the company during the last week of March, the same day M.’s fever set in. Guidelines for employers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that “if an employee is confirmed to have COVID-19 infection, employers should inform fellow employees of their possible exposure.”

Asked about workplace safety during Covid-19, Rosenberg, the Broadridge representative, said the company was “taking the most stringent precautions possible to continue to keep all associates healthy and safe,” which included decreasing production staffing by half to enable social distancing and disinfecting the work spaces multiple times a day. The cafeteria was closed on March 27, he said, and box lunches were provided starting March 29. Rosenberg added that the company’s Brentwood warehouse, along with another smaller, nearby facility, have onsite medical staff for associates and would treat workers with illnesses that emerge onsite regardless of whether they were employed by Broadridge or a contractor.

The threat posed by Covid-19 to warehouse workers has been the animating force in recent protests by Amazon workers, who have criticized the company’s efforts to protect them. Last Monday, Amazon workers staged a walkout at a Staten Island warehouse. (That same day, Amazon fired one of the central worker organizers, claiming he violated social distancing rules; the worker and activists regard the firing as retaliatory.) Recently, Amazon has agreed to some changes including a $2 raise and paid sick time for workers who have contracted Covid-19 or been asked to self-quarantine. Workers told the news media they viewed the changes as insufficient.

At TMG, workers are, if anything, more vulnerable. All of the eight current workers interviewed by The Intercept and Type Investigations said that, in the absence of paid sick leave and with the threat of being fired after missing two days, they felt pressured to keep showing up for work.

On March 18, Cuomo signed legislation that, effective immediately, guarantees paid sick leave for employees who have Covid-19 or have been ordered to quarantine. The Intercept and Type Investigations reached out to the New York State attorney general’s office, which is monitoring the treatment and safety of employees during the pandemic, for guidance on whether TMG or Broadridge may have violated the law. The attorney general’s office would not comment on the legality of Broadridge and TMG’s conduct, but a spokesperson said the office is now looking into the allegations and speaking with TMG workers.

Recently, following The Intercept and Type Investigations’s inquiries with Broadridge about workplace safety, staff from the company handed out gloves, masks, and hand sanitizer gel to TMG employees, according to a current worker. A Broadridge representative also announced that, beginning on April 6, the temperatures of all warehouse workers would be taken by Broadridge and anyone with a fever would be sent home. For K., the new measures were welcome news — but they came far too late. “This is what they should have done a long time ago,” K. said, “before everyone became infected.”