When Kishore Sharfudeen—a soft-spoken father of two from the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu—joined the hosiery manufacturer SNQS International Socks as a personnel manager in 2001, a new world opened up to him. Eight years as a junior lawyer had left him disillusioned, and his new employer, based in the city of Coimbatore, seemed to offer an easier living supplying European brands like Primark and H&M with knitted socks.

His main tasks were looking after the factory’s approximately 300 workers—mostly young women from villages across Tamil Nadu—by making sure their workplace and living accommodations met Indian safety and health norms. “I learned so much at that place,” recalled Kishore of his five and a half years at the factory when we met on a late September morning in the lobby of my hotel in Coimbatore. “It was a precious experience.”

It’s rare to hear praise about a sector that has long been synonymous with hyper-exploitative sweatshop conditions, but SNQS was an outlier, he said. While the workers were only paid minimum wage, or around $40 a month, he took pride in making sure the factory and the hostel were in good condition and that the workers ate a healthy diet and had enough free time to rest between shifts.

In fact, Kishore’s subsequent experiences in the industry made him realize just how unusual that was. The sock factory didn’t typify basic standards of safety and competence. As he would soon learn, it was about as good as things got.

Kishore entered the fast-fashion industry at a time of great transformation. The new millennium had brought with it an age of “corporate responsibility,” and Western brands from Gap to Benetton pledged to push their suppliers to respect international labor standards, prevent accidents, treat workers with dignity, and not use child labor. Amid these promises, the “social audit”—also known as the “ethical audit”—was born.

Modeled after financial audits, which hold companies’ books to basic accounting criteria, the social audit would be an analogous instrument to monitor and remedy worker rights abuses in global supply chains. Developed by NGOs and industry associations such as the American Apparel Manufacturers Association and the European Foreign Trade Association and promoted by major international brands and retailers, the social audit would nonetheless differ from today’s financial audits in two crucial ways: It would be voluntary and market-driven.

That means that it would offer factory managers an opportunity to have their workplaces inspected and would reward factories that maintained high standards with a competitive edge over their unaudited rivals. But the auditors would be employed by loosely regulated for-profit inspection companies that would compete for auditing contracts—a feature that Dr. Carolijn Terwindt, an independent legal expert on corporate accountability, says can undermine the certifications’ entire cause. “Financial audits are better regulated than social audits,” she said, “even though financial audits merely deal with monetary risks, whereas social audits are about people’s lives.”

Among the handful of auditing protocols adopted in the garment sector, the SA8000 standard is considered the toughest. Created in 1997 by the New York–based worker rights NGO Social Accountability International (SAI), it enjoys a reputation as one of the most stringent audits in town. In addition to baseline safety, wages, health, and other labor standards, the SA8000 expects a company to pay workers a living wage—not just the minimum—within two years of its first certification. Kishore said successfully getting an SA8000 as a factory manager “was like a feather in your cap”—and a near guarantee for orders.

Participating in programs like SA8000 has become a necessary part of doing business in the global garment industry. But interviews I conducted in the second half of 2019 with dozens of auditors, consultants, factory managers, and garment workers in India reveal that the social auditing industry is just that: an industry. My investigation paints a bleak picture. Audit firms put profits before workers. They aren’t held accountable by the nongovernmental organizations tasked with monitoring their work. Their inspections have failed to signal safety and labor violations, so tragic factory fires and accidents remain common.

That’s because there are flaws built into the social audit model. Since the audits are paid for by the companies being audited, firms have little incentive to protect workers. According to my interviews, the reports they create are consistently misleading. They are also inaccessible to the very people they claim to serve: Workers don’t have the right to know about the violations auditors might have found on the factory floor.

And yet retailers and clothing brands such as Gucci, Amazon, Walt Disney, and Walmart hold up their work with the audit industry—which includes SA8000 and a half dozen of its competitors—as a sign of their ethical commitment. The NGOs and industry groups that run and supervise these programs are now pushing for their adoption in supply chains as disparate as food and electronics. This means suppliers can no longer do business with big brands without these certifications.

Rana Plaza, an eight-story commercial building, collapsed in Bangladesh in 2013, killing over 1,000 people.Image: Mohammad Asad/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images

The social audit was born more than two decades ago and has since morphed into a global industry dominated by about a dozen multinationals competing for auditing contracts. Every year, inspectors from giants such as the French Bureau Veritas, the UK firm Intertek, and TÜV Rheinland in Germany audit thousands of companies across Asia and the subcontinent. To do so, firms must first obtain accreditation from the certification’s architect; if their chosen seal of approval is the SA8000, that involves applying for a license with SAI and, if granted, paying SAI an annual commission. To ensure its own standards are met, SAI is supposed to intervene if auditing firms prove sloppy or otherwise unfit for the job.

But there’s another layer to the complex auditing process. Manufacturers like Kishore’s sock company seldom go directly to the auditors for a review. Instead, they hire an external “certification consultant”—essentially a coach—to get them audit-ready, put them in touch with approved inspection firms, and see the process through.

Kishore was an exception: While seeking to obtain a certification for the sock factory in 2006, he decided to skip the consultant and go straight to RINA, an Italian inspection company authorized by SAI to hand out SA8000s that had an office near his factory. The auditors who showed up at Kishore’s doorstep on the morning of the inspection “were really impressed” with the state of the facilities, Kishore recalled, “and said everything looked perfect.”

They were so impressed that a few weeks later, RINA Managing Director for India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh K.T. Ramakrishnan called Kishore from RINA’s Indian head office in Mumbai to offer his congratulations. Then, he offered him a job as a SA8000 auditor.

Ramakrishnan, a mechanical engineer by training, liked to describe his job as “aimed at social justice and equality, consideration to humanity, and a motivated effort to ensure growth.” Kishore took him up on the offer, but not for any “social intention,” as he put it. “I have my job for my earnings,” he told me, “for my family.” The starting salary of $746 per month was nearly a third more than the sock factory’s, so the decision was an easy one.

It would not feel easy for long.

THE BLOW-UP

His own role wasn’t quite what he’d imagined, either. Per the SA8000 protocol, auditors were meant to be fact finders who, guided by a long and detailed checklist, follow a standardized evidence-collection routine: a factory tour in the morning, a bookkeeping review session after lunch, and worker interviews in the afternoon. But as he observed his colleagues interacting with management, he soon realized that, more than fact finders, they were salesmen too. What they were selling, Kishore came to understand, was a certification experience that was positive, relatively painless, and, crucially, would make clients want to hire RINA over a competitor when their next audits were due.

A latecomer to the auditing field, RINA was aggressively pursuing clients in South India at the time, with considerable success. Under Kishore’s manager, Subburaja Ayyasamy—a clever salesman who headed up the Tirupur office at the time and led RINA’s expansion across the South—the Tirupur office grew from a dozen SA8000 clients in 2006 to well over a hundred in 2010.

“Ramakrishnan praised our office for being great at marketing,” Kishore recalled, “but we got our clients by compromising all the norms.” Only a fraction of the health and safety hazards he saw while walking around clients’ premises made it into the reports to SAI, he said.

The document review sessions were as unnerving as the tours. Browsing through the documents, Kishore—who, trained as a lawyer, had a sharp eye for detail, and knew the industry from his years at SNQS—quickly concluded that many of the books were largely forged.

Sometimes, he said, fire and safety training records showed names of workers who, according to the attendance sheets he had just looked at, were not even present that day. Other times, the records he reviewed showed eight-hour workdays in factories where he understood 12-hour days to be the norm. From committee meeting minutes and wage stubs to appointment letters and overtime records, “most of the time, it was all cooked up,” Kishore said.

In a 2016 auditing guide, SAI notes that the credibility of its SA8000 certificate has suffered from “the inability or unwillingness of auditors to recognize” double books and false wage-hour records.

What’s more, Kishore had expected to be dealing with personnel managers, like himself in his former role. Instead, he encountered consultant after consultant, each hired by the factory to help them get certified. And they never seemed to enforce standards, as they claimed. Rather, per Kishore, their job was “to fake it.”

Interviews with workers were the most awkward part for Kishore. The purpose of these sessions is to verify details about wages and hours, and inquire about sexual harassment, union busting, and other forms of discrimination or abuse. But the auditors he observed in his first month “only asked them some leading shallow questions,” Kishore recalled, “like, ‘How’s your family doing?’ and ‘Everything fine here at work?’” The workers had “clearly all been instructed by their managers to tell us everything was fine.”

The whole audit ritual seemed like one big charade, and once he began conducting audits on his own, he was unwilling to play along.

Kishore’s main tasks were surveillance audits—which, under the SA8000 standard at the time, factory managers had to submit to every six months after their first certification. Officially, these audits come unannounced, but in reality, consultants hired by factories often plan the dates with auditors—a claim corroborated by former colleague Nikhil Shah. To Kishore’s annoyance, consultants often changed the audit dates at the last minute when they needed more time to prepare their clients, which would “totally mess up my schedule,” he told me. He complained about the problem in an e-mail to Ayyasamy in March 2009.

Kishore understood that for many suppliers, violations such as excessive overtime were hard to avoid because of the unpredictable order volumes and deadlines that Western brands often imposed. To deny these companies their certificate on these grounds would only make it harder for them to grow and stabilize their business. So, as a compromise, Kishore resolved to adopt a more practical audit mindset: for example, to accept false books without a fuss “as long as they at least looked perfect,” he told me. “If you ask for the real records,” he clarified, “you couldn’t pass any factory.” He also didn’t mind turning a blind eye to minor violations—an incomplete first-aid box or missing dust masks–if management promised to fix them later.

Even so, “he had too much of a letter-of-the-law mindset for RINA,” recalled his former colleague Shah in a phone call. “He kept clashing with [his managers] and the clients and the consultants about what issues to put in the reports and what to leave out.” For the consultants, said Shah, “the growth of their business depended on their success in getting companies certified with minimal efforts.” Kishore’s habit of demanding more-than-average improvements from clients undermined this success. “They wanted him to be more business-minded.”

Activists in Bangladesh demand safe workplaces for garments workers.Image: Mamunur Rashid/NurPhoto via Getty Images

RINA’s bottom line depended heavily on the goodwill of the consultants, though. That’s because these middlemen would handpick auditors for their clients and negotiate the terms on their behalf. RINA knew how to spin this dynamic to its advantage. To pursue new clients, the company ingratiated itself to the consultants by paying them “marketing fees” that could reach 10 percent of auditing revenue for every client sent their way, according to three people who worked in the industry.

As a result, said Shah, the vast majority of RINA India’s social audit clients came via a small handful of consultants: an arrangement that made RINA dependent on the very same people whose work (and clients) they were supposed to judge rigorously.

Kishore was confronted with the dark side of this arrangement: If the consultant found RINA’s audit was too harsh, he could simply take all his clients to a more lenient rival. This power dynamic, Kishore said, made some consultants so confident of RINA’s cooperation that they barely tried to make their clients look compliant.

So when, on March 23, 2009, Kishore e-mailed Ayyasamy to complain about the consultants, claiming that some of them sent him to factories “where I can’t even find traces [of] SA8000,” he was essentially told to just get on with the job.

The immense pressure to cut corners started to wear Kishore down. “I just couldn’t work my conscience,” he told me. Shah, whose main job at RINA’s Mumbai office was to review audit reports from across the country, noticed that “Kishore’s reports were noticeably more robust and detailed” than his colleagues and “usually found more problems.”

Shah shared many of Kishore’s concerns with RINA’s liberal audit style. One problem he observed was the practice of sending fewer inspectors to the factories than required in order to lower expenses. “I have come across SA8000 reports in which my name has been included as a team member,” Shah wrote in a 2008 e-mail to Ayyasamy and Kishore. “Please verify with me if I am available on that date. I can not be at two places on the same day!” (Almost two and a half years later, Shah warned his colleagues via e-mail that adding names to audit reports, in spite of “the numerous times that the south office has been informed to discontinue” the practice, was “turning out to be [a] recurring—yet unnecessary—nightmare.”)

Another tactic RINA used to save money was to undercount factory workers, a move that under SA8000 rules allowed auditors to spend fewer days on an inspection, according to Shah and Kishore. Shah worried about the practice at the time, “because obviously auditors risk missing out on important violations or safety risks if they don’t have enough people on-site.”

Copy-pasting findings from one audit report to another was another way to save on costs, said Kishore and Shah. Even RINA staff in Italy noticed. “Any company certified by Tirpur [sic] office has the same documentation, use the same forms,” wrote a colleague from RINA’s head office in Genoa named Achille Tonani in an e-mail to Ramakrishnan in January 2011. “[Two] companies have a supplier control plan identical to the last 20 company reviewed by me in the last months.… Is it possible?”

Kishore’s anxiety soared on January 18, 2010, when, after nearly two and a half years on the job, he had his most antagonistic client encounter yet. That day, he audited a knitwear manufacturer in Tirupur that had been given a clean slate by his manager six months earlier.

The place was a mess: missing fire extinguishers, obstructed exits, and workers visibly exposed to chemical fumes. (All these violations are mentioned in leaked e-mails between RINA and SAI.) He was alarmed at how young some of the workers looked and discovered that the firm withheld workers’ overtime pay.

But instead of providing Kishore with the age proofs and wage stubs to prove him wrong—as they must, under SA8000 protocol—management “threatened to report me to Ayyasamy,” Kishore said to me. “I told them to go ahead and failed them.”

Desperate for an intervention, Kishore reached out to his boss in Mumbai three days later. He forwarded Ramakrishnan a heated e-mail exchange between himself and Ayyasamy, in which he lamented “the quality of audits being done and the compliance level of many of our clients.”

But the audit was the least of Ramakrishnan’s worries. More significant to RINA’s bottom line was the firm’s relationship with its certification consultants—a relationship Kishore’s auditing style was gravely undermining.

Of the consultants Kishore had angered with his demanding auditing style, a man named A. Faizall was the most imposing. A Tirupur-based business graduate with a long red beard, Faizall had special status at RINA at the time, according to Shah and Kishore, because of his large network of clients and the business he brought to RINA. To this day, Faizall remains active in the Indian certification industry.

Kishore thought his relationship with Faizall was basically cordial. Little did he know that Faizall would write a letter to Ramakrishnan, who was still running RINA India, on January 19, 2010, accusing Kishore of “demanding favors” from manufacturers and threatening to fail their audit if they didn’t pony up. The threat implicit in Faizall’s letter was that he would take his clients to a competitor if Kishore didn’t make it easier for clients to pass audits; Kishore believes the letter was part of a ploy to get him fired.

Faizall, on his part, claimed in a recent interview in Tirupur that he didn’t remember why he wrote the letter. He didn’t recall thinking Kishore had ever extorted his clients, either. His only lasting impression of Kishore was that “he was a practical man.” Ramakrishnan and RINA declined to comment on whether they’d received credible corruption allegations regarding Kishore; Shah found the idea of Kishore extorting clients extremely unlikely.

Ramakrishnan’s e-mails to Kishore grew harsher and colder in tone. Without offering specifics, he wrote Kishore on April 24, 2010, that he had received “unfavourable feedback from consultants and clients,” accused him of lacking a “spirit of team work,” and urged him to focus more on RINA’s bottom line.

Kishore countered his boss with the warning that RINA could lose its credibility if it refused to change course. “If SAI does a surprise visit” in any of the factories he had warned him about, “the credibility of RINA will be stripped forever.” When, a few months later, Kishore received an e-mail from Rochelle Zaid, a senior director at SAI in New York, it briefly looked like his prediction was right. Someone had filed a complaint to SAI about RINA’s sloppy auditing practices in Tirupur, Zaid wrote, and recommended Kishore “as a resource who can share some of the information regarding these allegations.” Was he willing to speak?

Kishore felt conflicted. He wanted SAI to intervene, but by coming clean to SAI he would breach his nondisclosure agreement with RINA, giving it a perfect excuse to fire him. He didn’t end up having to decide. When he came home from work on August 30, his wife handed him his termination letter, delivered earlier that day by a courier. RINA had fired him for not meeting its productivity expectations.

Kishore, now unemployed with nothing to lose, decided to file his own complaint with SAI. In the following months, he sent SAI dozens of audit reports and internal communications with evidence that RINA routinely falsified company information, sent too few auditors to their clients, copy-pasted content from one report to another, and regularly allowed consultants to inspect their own work as members of RINA’s auditing teams.

A year passed; SAI investigated, cleared RINA of wrongdoing, and closed the case in an e-mail to Kishore on October 6, 2011. It justified its decision by arguing that copy-pasting of audit content does not necessarily harm the quality of audit reports; that it only found one case where an auditor had been erroneously double-booked, and that RINA had updated its conflict of interest policies and fixed the consultant-doubling-as-auditor problem.

What SAI neglected to mention was that what most alarmed Kishore—that to shorten inspections, auditors undercounted the number of people working in their clients’ factories—had caused concern at SAI as well. In fact, after SAI had reached out about the issue months earlier, Ramakrishnan instructed his team via e-mail to correct their records, “with particular reference to the actual workforce and the man days utilized.” The organization in charge of accountability, then, knew it had a problem; but instead of penalizing the auditor, it kept that knowledge to itself, allowing RINA to resume business as usual.

THE DISASTER

On September 11, 2012, a massive fire broke out on the ground floor of Ali Enterprises, a garment manufacturer in the Pakistani city of Karachi. Just a few weeks earlier, RINA auditors had declared the company safe and sufficiently compliant with the SA8000 standard; more than 250 workers noticed the flames and the smoke too late. Trapped behind barred windows and locked emergency exits on the top floor—where most of them had gathered to collect their wages—and without access to functional fire extinguishers, they perished. In a reconstruction of the fire, researchers from Forensic Architecture, a research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London, have shown that a functional fire alarm alone would have been enough to dramatically reduce the loss of life.

Image: The Nation

The dysfunctional fire alarm was one of many egregious safety hazards that the auditors should have required their client to get fixed. The absence of exits on the top floor and evidently falsified fire and safety training records were others. When, in the wake of the tragedy, human rights groups demanded to see this audit report, both SAI and RINA demurred, citing confidentiality. RINA maintained that on the day of the audit, Ali Enterprises had been compliant with the SA8000 standard.

The European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, an NGO based in Berlin, obtained a copy and showed it to survivors and former workers of Ali Enterprises. They found it full of inaccuracies: In affidavits submitted to a German court in a 2015 lawsuit against the German retailer Kik, workers seeking compensation from the Ali Enterprises buyer pointed out that the photos accompanying RINA’s audit report—all supposedly screened by the auditors on the day of the audit—were at least six years old and claimed that the building, with its cracked walls, broken ceilings, and barred windows, felt like a “jail can.” In 2019, the court dismissed the suit because of statutory limitations.

SAI commissioned its own investigation into the fire in 2012, whose results echoed many of the workers’ claims. It found that the auditors missed or ignored many obviously dangerous safety violations and had accepted fire safety training records that were evidently fake. It also found that Ali Enterprises employed hundreds more workers than RINA claimed it did.

Kishore had warned SAI over a year before about RINA’s dangerous auditing practices. He had told SAI that he believed RINA undercounted the number of workers at its clients not by accident but by strategy. SAI didn’t listen. After such a tragedy, would the American NGO finally sever ties with the Italian auditor?

Not quite: SAI suspended RINA only from auditing in Pakistan. Everywhere else, workers still depend to this day on these audits to keep them safe.

Half a year later, tragedy struck again, when the Rana Plaza factory complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh, collapsed, killing more than 1,134 garment workers and maiming thousands more. This time, it was RINA’s competitor the German market leader TÜV Rheinland who was found wanting. During an audit commissioned by BSCI—an auditing competitor favored by Amazon and European brands like Mango—TÜV Rheinland auditors had found the workspace of their client, a garment manufacturer housed in the Rana Plaza complex, safe, with “strong construction quality,” just months prior to the collapse. In reality, the building was not safe at all; the top three floors were built illegally, according to local authorities cited in The Guardian shortly after the disaster.

Neither SAI nor its peers suspended TÜV Rheinland. In 2018, the company conducted around 10,000 social audits, mostly in Bangladesh, India, and China.

Financial incentives are a big part of the problem with social audits. But workplace culture—including the widespread use of nondisclosure agreements—contributes, too. As Kishore learned, auditors risk losing their jobs if they decide to tell workers about the safety violations in their workplaces. “Full transparency and workers involvement are an absolute must for any monitoring initiative,” says Mark Anner, an associate professor of labor and employment relations at Pennsylvania State University. “As long as workers are not driving the oversight efforts and can’t even scrutinize the reports, these auditing firms will continue to create a very distorted picture of progress that puts workers at risk and crowds out efforts for more sustainable and effective mechanisms for decent work.”

To make things worse, well-connected consultants like Faizall act as masters of the auditing universe, an attitude largely fueled by their position as middlemen between auditing companies and their clients. Of the 13 auditors I asked about the role of such consultants, 11 expressed frustration with consultants’ power over their employers and their frequent attempts to dictate what auditors can include in their reports. This kind of top-down pressure compels many auditors to act as Kishore had: become “practical” about audits, weigh “intent” of their clients against the actual violations they found, negotiate with their managers on what compromises to make.

An auditor who asked to be referred to as Shree offered a typical example of such a compromise: “When I tell my manager that the fire safety training records look fake or that the overtime records don’t add up with the wage stubs, he usually tells me to take it up with the consultant who got us the client and tell him to fix the paperwork to make it look consistent.”

Ultimately, it’s the office managers who decide what does—and doesn’t—go into the audit report. And between double books, scripted interviews, and dodgy deals with consultants, dangerous factories appear benign, even ethical, on paper. There’s even a term some auditors use to describe this process: “eye wash.”

Workers sometimes have their own reasons, absent management pressure, to play along with the “eye wash” and deny working overlong hours: Overtime offers them a chance to bring their wages a bit closer to totaling a living wage, which the Asia Floor Wage Alliance puts at $390 a month in India. The SA8000 is the only social auditing scheme that requires companies to pay employees a living wage within two years of certification, but it’s vague on what that means. In leaked audit reports of two garment factories in Tamil Nadu, the living wage was calculated so that it ended up at $60 a month at one factory and $80 at the other. The auditors reasoned that their client, by paying their lowest-paid workers just over the legal minimum of $120, not only met SA8000’s living wage requirement but exceeded it by $60 and $40 respectively.

Some auditors might try to extract the truth from workers with original questioning techniques. But, perversely, they risk inflicting extra stress on workers. “Many workers are so scared of audits,” said Shree. “Sometimes they start crying when I just ask them for their names” or “give answers to questions that they’ve been told come next.”

I got a taste of this anxiety myself during a group interview with three workers from a Tirupur-based garment factory RINA had audited. I met the women in one of their homes; initially, they were open about how their managers expected them to lie to auditors about wages and hours. But when I asked how much overtime they actually made, the atmosphere in the small brick room immediately turned tense. After exchanging some anxious looks, one of them turned to my interpreter and asked her what all three of them wanted to know: “Is she a buyer?”

Once we had reassured them that we would not expose their boss or try to get his SA8000 withdrawn, the women admitted what two of their colleagues had already told us earlier that day: that many women in their factory work 12-hour days and that their workweeks often exceed 65 hours.

Many auditors and consultants I spoke to blamed the brands, rather than the factory managers, for the prevalence of fraud and eye wash. They pointed to the detrimental impact that rock-bottom prices, rushed deadlines, and the lack of order security have on wages, excessive hours, and production pressure. “Factory owners always complain about how every year brands want to reduce the price,” a consultant from Bangalore told me.

“You want the same order? Brands tell them, you have to do it for less next time.”

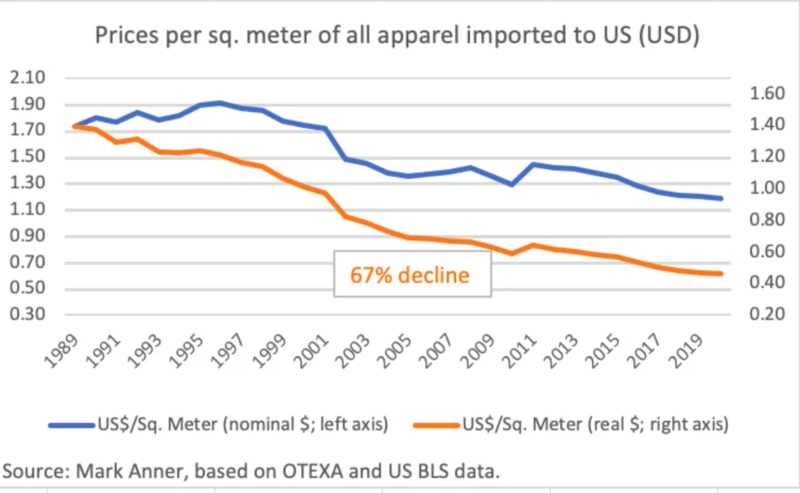

Mark Anner wasn’t surprised by these comments. For the past couple of years, Anner has extensively investigated Western brands in Vietnam, Bangladesh, and India. After surveying and interviewing hundreds of workers and factory managers in these countries and studying international trade data of the past two decades, he concluded that “predatory” pricing worsens work conditions.

“I found that buyers’ squeeze down on price, their obsession with speed to market, and the dramatic fluctuations in order volumes to directly contribute to below-subsistence wages, forced overtime, union avoidance, and extreme, sometimes violent pressure on workers to meet unrealistic production targets,” he told me over the phone.

Anner noted that instead of audits, workers need transparent, binding monitoring accords between brands and unions. Under such agreements, he said, “if brands fail to meet their obligations there should be mechanisms in place for workers to hold the brands to account.”

Four former SAI employees whom I contacted in the process of reporting this story said they left the organization precisely for this reason: The certification system, thanks to its corporate-driven structure and its lack of transparency and worker involvement, benefits businesses more than workers.

Far away in South India, Kishore reached a similar conclusion. After his stint at RINA came to an end in 2010, he started his own legal advisory practice, which he still runs today. He advises companies throughout South India on personnel management and signs off all his e-mails with his business motto, “It is better to prepare and prevent than to repair and repent!!,” which, he said, was inspired by his time at RINA.

SAI declined to comment on Kishore’s account or on his allegations about the consultants, but insisted its certification is the best-equipped to minimize the “brand pressure, cheating, and corruption that is seen in the social auditing industry today.”

Many of Kishore’s former managers stayed on in the industry: Ramakrishnan and Ayyasamy, for example, have both joined SAI’s competitor WRAP, which was created by an American trade group and remains popular with US brands. RINA continues to conduct audits for SA8000, WRAP, and other several certification protocols.

Faizall, who continues to help clients across India obtain such certificates, does not believe brands will ever pay suppliers enough to fulfill the supposedly ethical demands of these standards. When I asked him how, given these structural limits, he views the role of auditing companies, NGOs, and consultants like himself who run and operate in the system, his answer was straightforward.

“It’s all about business,” he said, “No one is here to do service.”