Elvis had a simple request for the judge. Could she call his lawyer again?

“There’s no reason for me to call back, sir. I called and he didn’t answer,” Judge Joy Merriman told the Guatemalan detainee who was attending the hearing as part of his asylum application. “I’m not going to give him a second chance.” His lawyer had asked to appear in court by phone, which the judge allowed. She had called the lawyer and gotten his voicemail.

“The court has very limited time and resources,” the judge said. “I still have 40 more cases this afternoon. My interpreter, the Department of Homeland Security’s attorney, my legal assistant, they all need to take a lunch break, because this is a very heavy docket.”

It was a small moment in a long sequence of indignities that Elvis had faced since he fled gang threats at home and was picked up by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents while crossing the Texas border with his then-pregnant wife Wendy in February of 2019. He was one of the detainees caught up in the widening crackdown by CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) under the Trump administration. But the problems didn’t stop with the detention: Elvis’s asylum effort came at a time when a slew of policy changes and Department of Justice rulings have snarled the court system in myriad ways.

In 2019, we set out to document the fallout from those changes, observing New York City’s immigration courts every single day for three months. When we began reporting this story, we knew the courts were struggling to keep up with the influx of cases and the pressure the Trump administration was putting on them. At the time, the administration had just set a case quota for all immigration judges to complete within the year — an effort to deal with the case backlog that had grown in New York State from about 65,000 uncompleted cases in fiscal year 2015 to roughly 124,000 in fiscal year 2019. We also knew that judges were setting bonds higher and that nationwide, being granted asylum was becoming harder. We wanted to see why, and how.

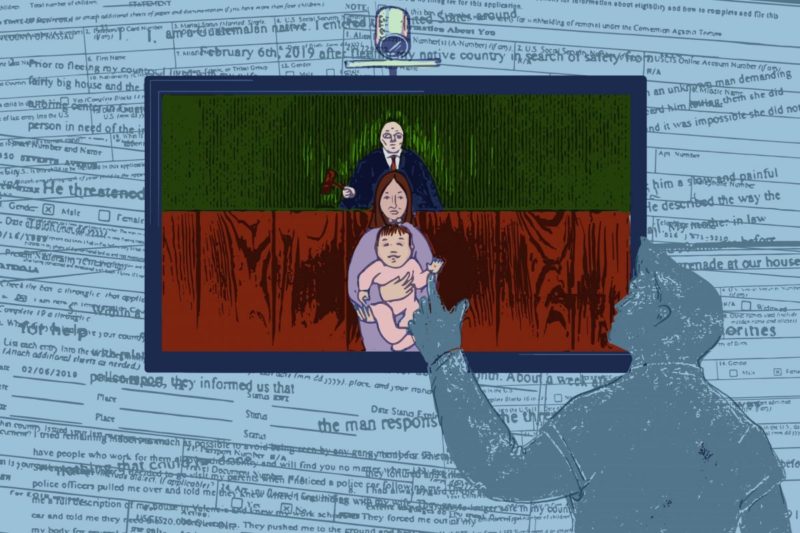

Image: Alex Charner for Latino USA.

We hired six reporters to take turns surveying New York’s immigration courts from when they opened until when they closed, five days a week, for three months. Their mandate was to try and watch as many individual immigration court proceedings as they could, and to document how the system was working — and how it wasn’t. Over that period, they were able to observe more than 200 hearings, which greatly informed this episode of Latino USA.

Our reporters witnessed a system clearly overwhelmed and overburdened by the logistical task of holding hundreds of hearings per day. One of the hurdles to asylum claims we witnessed was pressure on judges from the DOJ and Trump administration to push cases forward quickly, leaving immigrants and their lawyers little time to prepare evidence. The court’s scheduling system was also rife with errors, leading many people to miss their court dates when they were rescheduled without notice or to travel far distances to attend a hearing that was canceled that day. We observed the hearings of immigrants who, after years, had their court cases randomly reopened due to a ruling by Jeff Sessions. The court’s videoconferencing system — which is being used more frequently due to a growing detention population — would often malfunction, which sometimes led to cases being rescheduled and immigrants spending longer in jail for reasons out of their control. We also witnessed an overall decline in judges’ abilities to make decisions on a humanitarian basis, the result of a series of policy changes and DOJ actions, which chipped away at judicial discretion.

These problems had serious real-world impacts on the immigrants and their cases. During one hearing, an ICE prosecutor announced they had lost a woman’s file, forcing her to start her case again. We witnessed detained immigrants get their hearings pushed back a month after the video-teleconferencing system they were using to appear in court broke down. In another hearing, we heard from a man who had spent about a month in detention because the court had sent correspondence, saying that he was free to leave detention if he paid his bond, to the wrong address. In the hearing it came out that he had sent the court a notice that he had moved to a new address — a fact that was verified when the judge flipped through his file and found the slip of paper.

“I apologize to the client, I apologize to the attorney,” the judge said.

Our reporters faced considerable pushback from ICE attorneys, court staff and immigration judges. On one occasion, an ICE attorney stopped a court proceeding to send an email to a superior, asking if our reporter was allowed to be in the courtroom. John Martin, the Justice Department’s local press officer assigned to the immigration courts, eventually sent a department-wide email letting judges know that they should expect our presence in the court — which are open to the public with some limitations — for a number of months.

When we heard Elvis’s story, we knew we had to tell it, and joined with Latino USA producer Alissa Escarce to follow him and his wife, Wendy, for six months as they wound their way through the immigration court system. Elvis’s experience in immigration courts reflects other cases we witnessed throughout this project. He fled a violent gang in Guatemala, was represented by an attorney who, in the middle of his case, was suspended from the practice of law for a year because of misconduct towards his immigrant clients, was held for months for minor procedural glitches, and was eventually denied asylum without clear explanation by a recently hired immigration judge.

At the end of the hearing where he was ordered removed back to Guatemala, the judge asked him if he wanted to appeal. After months of detention, he said no. He no longer trusted the court system nor felt he had any agency in his fate.

“I do not wish to appeal,” he told the judge, knowing he would leave this country without his wife and child. “What for? It would be useless.”

Listen to Elvis and Wendy’s story here:

Ralph Ortega, Phoebe Taylor-Vuolo, Hannah Beckler, Irene Spezzamonte, Grace Moon and Irene Tang contributed reporting to this project. This project was created by Documented, in partnership Latino USA and with the nonprofit newsroom Type Investigations’s Wayne Barrett Project.