This feature contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault, rape, and domestic violence which may be disturbing to some readers.

In the years before Nicole “Nikki” Addimando stood trial for second-degree murder, she was a stay-at-home mom, her days filled with preschool drop-offs and singalongs. “A crafty, Pinteresty mom,” said one friend. “The proudest mama on the planet,” said another. In the fall of 2017, Nikki and her two small children, Ben and Faye, were living with Christopher Grover, Nikki’s boyfriend of nine years and the kids’ dad. The family rented a three-bedroom basement apartment on the east side of Poughkeepsie in upstate New York. Nikki, then 28, had worked as a preschool teacher, but when she was pregnant with Ben in 2012, the couple decided she would leave her job to raise him — and, two years later, Faye. With money tight, Nikki found free activities for the kids throughout the Hudson Valley, a stretch of intermittently tony and depressed suburbs: apple-picking, corn-maze-walking, roller-skating.

Nikki skimmed five feet and 110 pounds and wore her curly black hair ironed long and straight. Chris, 30, was only a few inches taller, notable for his bald head and small but muscular frame; he spent his days at a gymnastics studio, where he was a head coach, bringing in the family’s main income. They often struggled on Chris’ wages. On the worst days, Nikki borrowed cash from the kids’ savings to buy essentials, replacing the money later. At night, she sewed baby booties that she sold online for $28 a pair.

Chris was well-liked by the young girls he coached. “An all-around nice guy,” his boss told me. “A diligent father who prioritized his family,” a former gymnast wrote. In his free time, he enjoyed playing video games, watching anime, and practicing tae kwon do. He’d learned to make amateur movies in filmmaking classes at community college. He was close with his parents and his younger brother. On Sundays, he visited them at their rural home north of Poughkeepsie. At first, Nikki went along, but as the years wore on, she took to staying home. She had too many injuries, no more excuses to casually repeat: a tendency to bruise easily, a fall down the stairs, her own relentless clumsiness.

On September 27, 2017, at around 10 a.m., two caseworkers with Child Protective Services arrived at Nikki and Chris’ apartment on Van Wagner Road. Six days earlier, according to CPS notes, an anonymous caller had reported that “on a weekly basis, the mother has had visible bruises to her face and chest.” When the caseworkers arrived, they recorded that Nikki denied being threatened. A caseworker spoke with Chris, who told them he had no criminal history, substance-abuse issues, aggressive behaviors, or mental health diagnoses. The caseworkers talked to the kids. Ben said his parents yelled about adult things, that his father grabbed his mother. “Normal fights,” Chris told CPS. “All parents argue,” Nikki added.

One caseworker asked Nikki if there were weapons in the house. Nikki lied: “No.” The caseworker scrawled on paper and discreetly showed it to Nikki: “Are you safe right now?” Nikki nodded. The caseworkers did not find cause to take immediate action and asked for the names of friends and family who could provide more information. Nikki, terrified her kids would be removed, texted her sister, Michelle Horton, whose contact information she had given to CPS: “Mention no injuries. I’m a good fucking mom. He’s a good dad.”

For six years leading up to the killing of Christopher Grover, the Town of Poughkeepsie Police Department had records that described Nicole Addimando as a victim. The police department in nearby Hyde Park, the Dutchess County Department of Health’s Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner Program, the New York State Office of Victim Services, Family Services of Poughkeepsie, the domestic violence agency Grace Smith House, and the Dutchess County district attorney’s office had all identified or assessed Nikki as a survivor of physical or sexual assaults. CPS had approached her as an at-risk woman. And after Nikki’s trial, 20 community members wrote the judge letters of support for Nikki, saying they had noticed black eyes, bruises, abrasions around her neck and wrists, lesions on her chest, how she winced when she sat, and that she wore scarves and long sleeves in the summer.

But despite having access to these resources, despite the fact so many people knew or suspected she was being abused, Nikki was never able to find safety.

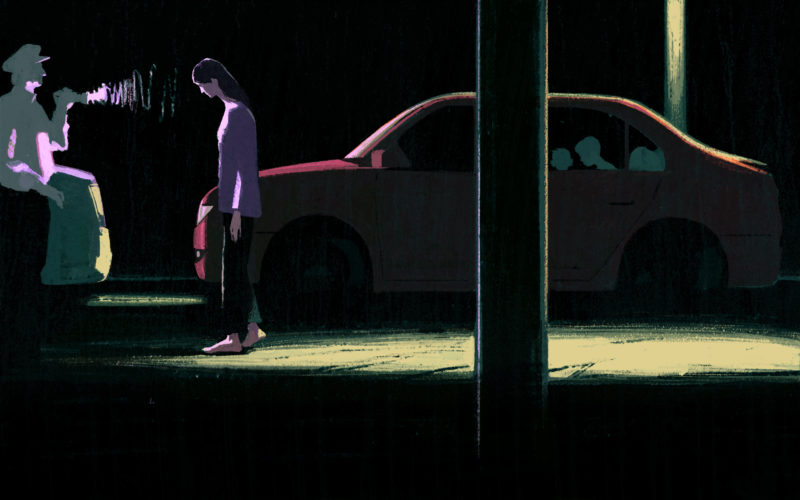

Nikki never denied that in the early morning hours of September 28, 2017, she shot Chris in the temple, pressing the pistol so tight it branded his skin. She then gathered their sleeping children and fled their home. Just after 2 a.m., a police officer pulled up behind a red car stopped at a green light and, assuming the driver had dozed off, hit his air horn to rouse them. He had not expected a young mother would get out and start talking about a body “just laying on the couch.” He listened as Nikki — “crying, shaking” and “distraught,” he wrote in his report — started to detail the events of the night.

In dashcam footage, Nikki stands on the pavement, illuminated by a streetlight’s purple glow. She is slight and shoeless. She tells the officer Chris pulled the gun. They struggled, it fell, and she grabbed it. He threatened her. She lunged and pulled the trigger.

“Oh my God, he’s dead,” Nikki says in the video. “It was self-defense. … Oh my God, it’s over.”

Image: Hokyoung Kim

Nikki told the officer at the stoplight about the CPS visit and Chris’ curiously calm demeanor. She told the officer they’d later had sex, which wasn’t like their usual “really violent” sex, though she still bled into her underwear. “Was it consensual?” the officer asked. Nikki indicated it was not. “But I didn’t fight him.” She clutched her stomach and asked what was going to happen. The officer reassured her: “No one’s taking your kids,” he said. “As of right now, you’re not in any trouble.”

He stepped away, called a colleague, and had a conversation, which was captured on the dashcam, where he relayed a sense of disbelief. “She said [the shooting] was immediately during the struggle,” the officer said. “The more and more she talks, I don’t really think it was during the struggle. I think it was after and maybe emotional.”

At around 2:30 a.m., Nikki’s friend Elizabeth Clifton met her at the stoplight and followed Nikki and the police to the station. Clifton would wait with Ben and Faye while Nikki was questioned. “I’ll be right back,” Nikki told the children. Nine months would pass before they saw each other again.

During Nikki’s initial police interview, a detective read her Miranda rights but assured her the questioning was a formality. “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do,” Nikki told the officers. “I would like to hear your side of the story,” the detective said. Again, Nikki began to relay the events of the evening, intermittently circling back to the past, recalling a paper trail of abuse: There were some exams on file at the local hospital detailing several rapes and assaults. Her therapist, whom she met through a referral from a domestic violence agency, had “a lot of documentation.” There was a detective from a nearby town who was “kind of aware.” About 30 minutes in, Nikki seemed to emerge from a fog. “It’s like — obviously self-defense, right?” she asked.

“I can’t make that determination right now,” the detective said.

“Should I need a lawyer then?”

“Do you have anybody you deal with, or are you just going to pick one out of the phone book?”

Nikki intimated she didn’t know a lawyer offhand. The detective left, and she waited silently for 23 minutes, then knocked on the door inside the room. “Excuse me,” she said. “Can somebody let me know if the kids are okay?”

In the evening, officers handcuffed Nikki and transported her to the Dutchess County Jail. According to a woman incarcerated at the jail multiple times, Nikki would have followed a process: shake out your hair, lift your arms, bend over for a guard in plastic gloves, and trade in your clothes and belongings for an orange jumpsuit, knock-off Keds, a scratchy bedroll, mini soap, and a travel-sized deodorant stick. Most people threw away the deodorant because, counterproductively, its application worsened body odor, but Nikki saved hers. She rubbed it on old magazine pages to extract color for her art: sketches of her and her children, collages of their photos, glued with toothpaste. “We are knit with one another,” she wrote in looping script on one of the collages.

I first heard about Nikki’s case in December 2018, and a month later I met Michelle Horton and Elizabeth Clifton at a coffee shop in Poughkeepsie. The women were nervous and formal. Neither had experience with the legal system nor were they certain how to contend with media interest surrounding Nikki’s case, which made the cover of the Poughkeepsie Journal.

Clifton and Horton had only met after Nikki’s arrest, first speaking on the phone on September 28, 2017. Until then, Horton told me, her family had been “dumb and blind” to Chris’ abuse. Clifton had been Nikki’s confidant. “He was really bad, Michelle,” said Clifton on that initial call. Eighteen months before the shooting, Clifton, a former social worker and Ben’s music teacher, had gently but persistently confronted Nikki. After initial denials, Nikki admitted she was being hurt at home. Later, Clifton says she learned Nikki was physically and sexually tortured on a regular basis. “She always said to me, ‘He’s a good dad, a good coach, and nobody will believe me,’” Clifton told me at the coffee shop. Horton added that, indeed, the prosecution was not convinced by Nikki’s claims and was planning to argue the killing was “premeditated and she planned this.” Horton hypothesized their strategy would be to make Nikki “look like a non-credible slut.”

After that meeting, I began reporting this story in-depth, digging through tens of thousands of pages of documents. I attended nearly every day of the trial and subsequent hearings and spoke with attorneys, experts on sexual and domestic violence, community members, and, after nine months of work, Nikki herself.

On her first day in jail, Nikki was assigned a public defender, Kara Gerry, who began investigating her case. Nikki had admitted to several friends that Chris was abusive, and a handful knew the more gruesome details: A midwife who treated Nikki for genital and bodily trauma; two forensic nurse practitioners who recorded the aftermath of rapes and assaults; Sarah Caprioli, a therapist who worked with Nikki for two years; and Clifton, who had seen bruises, blood, and weapons hidden in the back of a closet.

Gerry reviewed medical records, sexual assault examination records, and photos and spoke with “dozens upon dozens of witnesses who had seen these injuries,” she told me, including a handyman who had repaired a shattered glass door after Nikki had been slammed against it. According to Gerry, Nikki had told the handyman the door had been damaged by a rock before telling Gerry otherwise. “I feel like you become a good judge of character in my line of work,” Gerry told me. “Based on my interviews with the witnesses, I found them very credible.”

Gerry was pitted against Chana Krauss, an assistant district attorney from neighboring Putnam County. (Typically, a prosecutor from Dutchess County, where Poughkeepsie is located, would have handled the case, but since the Dutchess County DA’s office had been involved with investigations concerning Nikki’s victimization, the office recused itself.) Krauss is a compact, energetic 54-year-old brunette with a Brooklyn accent, a penchant for heels, and a 29-year prosecutorial record, primarily focusing on special victims and violent crimes.

Image: Hokyoung Kim

Several potential defense witnesses, unaccompanied by legal representation, submitted to questioning at the DA’s offices under oath. Among them was Caprioli, who has worked with prosecutors in her capacity as a victim’s advocate. She met with Krauss twice and told me she initially believed Krauss was acting in a “spirit of collaboration.” “In the first interview, she seemed understanding and sympathetic, but when I came back for the second interview, her tone was different … she has been going for blood ever since.”

A week before the scheduled grand jury presentation, Krauss moved to have Gerry, who had been preparing Nikki’s defense for almost eight months, removed from the case due to a conflict of interest with a past client of the office. Though Gerry “strenuously opposed” what she called the “11th-hour application,” the judge granted Krauss’ motion. Nikki was then assigned a public defender from a nearby county, but that office was in a state of flux, and Nikki’s attorney would be temporary. Horton told me she and her family felt “the public defender’s office seemed like a very unstable choice.” Within several days, they scrambled to borrow $60,000, mostly from a friend’s retirement savings.

Nikki retained a new defense team, John Ingrassia and Ben Ostrer, who Gerry briefed and to whom she handed over her files. Ingrassia is a slender, rangy former prosecutor, with a specialty in DWI hearings and a reputation as an excellent trial attorney. Ostrer is a relentlessly friendly career defense attorney with white hair and ruddy cheeks and expertise in forensics. When I first met them in a windowless conference room weeks before the trial, the mood was tense. Ingrassia was taciturn and skittish while Ostrer paged through a book called Defending Battered Women on Trial. The men were worried any comments they made to the media could hurt their client. Ostrer would only say the case would hinge on whether or not the jury believed that Nikki was “justified when she pulled the trigger.”

In self-defense cases where a woman has killed a partner, the criminal justice system struggles to categorize her. Ninety-six percent of intimate partner murder-suicide victims are female, and almost all are killed by men with firearms; four women a day die of domestic violence. At first glance, Nikki seemed to skirt the statistics only in her refusal to take a bullet. But in doing so, she was plunged into a system that demands black-and-white categorizations: Offenders kill, and victims die; offenders are monsters, and victims are angels. “So, if your abuser is not a monster and if your victim is not an angel, they are not ‘victim-abuser’,” Leigh Goodmark, a professor of law at the University of Maryland and the author of Decriminalizing Domestic Violence, told me. “Very few people exist on these binaries.”

The government keeps scarce data on this phenomenon, but the advocacy group Survived and Punished estimates thousands of people who have defended themselves from physical or sexual violence have been “disappeared” into women’s prisons. Commonly, a prosecutor challenges their credibility. “Women are not believed,” said Rachel White-Domain, an Illinois post-conviction attorney who works with incarcerated survivors of domestic violence. “Women of color are never believed.”

Survived and Punished’s New York chapter has examined and disseminated the cases of women currently incarcerated for acts of survival, most serving time on murder or manslaughter charges. Kelly Forbes, who emigrated from Trinidad and settled in Long Island, reported that her abusive husband — who had prior convictions for sexual assault and attempted murder — woke her up one night by attacking her with an electrical cord, but she strangled him instead. She is now serving 21 years. Tanisha Davis, a Black single mom from Rochester, had plenty of evidence of the abuse she suffered at the hands of the man she killed, including multiple 911 calls, two orders of protection, and an altercation recorded in a voicemail message minutes before the stabbing. The jury sided with the prosecutor, and Davis was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

But Nikki conformed to the stereotype of the “perfect victim”: a petite, White, suburban stay-at-home mom. She shot Chris eight days before the Harvey Weinstein story broke and the nation began a reckoning with the believability of survivors and the endemic nature of assault and abuse. “It was the beginning of the #MeToo moment, so I was feeling almost hopeful,” Rachel Foran, an organizer with Survived and Punished New York, which provided support to Nikki’s defense campaign, told me.

And then there was the enormous amount of evidence of abuse Nikki had amassed. Caprioli would testify that years earlier, with her help and encouragement, Nikki had begun documenting injuries, planning for a day when she might leave Chris and face a custody battle. After two attacks, Nikki had gone to her local hospital, which ran a state-funded program that allows sexual assault victims to document assault without involving law enforcement. The nurses’ records, gathered by the defense, contained photos of extreme injuries to Nikki’s body and genitals. After three attacks, she had seen her midwife, who recorded a prolapsed vulva, a swollen and bleeding vagina and anus, and bruises on her body. She also had snapshots from Facebook and Instagram, usually posed smiling with her kids, that revealed, upon examination, a black eye obscured by large sunglasses, a bruised breast, a bruised cheek.

Some instances of sexual torture had been recorded and uploaded to Pornhub, a popular streaming site. In 2014, Nikki told a therapist Chris was taping their sexual encounters without her consent. She brought a video to the office, which, the therapist confirmed to me, showed a man who looked like Chris having sex with her as she asked him to stop. By summer 2014, Nikki was seeing Caprioli. She disclosed that Chris had begun watching an increasing amount of torture porn, which he seemed to be trying to mimic (a police extraction report of Chris’ phone, from December 2017, showed many deleted searches for “forced” sex videos). Caprioli found a Pornhub channel that featured Nikki being sexually and physically tormented, took screenshots, and tried to convince Nikki to begin criminal proceedings.

Kellyann Kostyal-Larrier, executive director of Fearless!, an upstate agency that supports survivors of domestic and sexual violence, consulted on Nikki’s case with her defense attorneys. “You had more evidence here of her abuse than I have ever seen,” she told me.

With this evidence in hand, the attorneys entered into plea bargain negotiations. Nobody involved in this case would comment on the offers made by Krauss, except for Ostrer, who said: “None were agreeable to Miss Addimando.” Nikki decided to go forward and make her case before a jury.

***

People v. Addimando began on March 13, 2019, in a wood-paneled courtroom on Market Street, a row of rundown storefronts and municipal buildings in downtown Poughkeepsie. Judge Edward McLoughlin, a former Dutchess County ADA, presided over the room, which, for the duration of Nikki’s trial, was packed: Nikki’s supporters, in purple for domestic violence awareness, sat on one side, and Chris’ supporters sat on the other.

Nikki slumped at a nearby table, pulling the sleeves of her cardigan over her thumbs. In the months before the trial, she had been on electronic monitoring and house arrest, living at her dad’s place; Horton had permanent custody of Ben and Faye; and the sisters, knowing Nikki’s future was uncertain, decided the kids should stay with Horton so as not to risk another upheaval.

Krauss stood before the jury and opened with a text message Nikki had sent to a friend: “I haven’t figured out a way to kill him without being caught so I’m still here.”

“The evidence will show that just five weeks before Christopher Grover was killed by the defendant, Nicole Addimando, she sent that text message. And then on September 28, 2017, everything she said and everything she did was to avoid being caught.”

During a New York State criminal trial in which the accused claims self-defense, the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt the defendant was not justified in using deadly force. To find a defendant justified, the jury must assess whether or not a “reasonable” person in the same circumstances would have also believed themselves to be under lethal threat.

“Before a prosecutor brings a case, they have to have a good-faith belief they can prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt, and once you have that belief, you make the facts fit your worldview,” Goodmark, the University of Maryland professor, told me. “Prosecutors are fairly uninterested in a person’s status as a victim once she becomes a defendant.”

At the heart of any trial of a woman in Nikki’s situation is the question of believability: Do the police, the prosecutor, the judge, and the jury believe the defendant is a victim who, at a crucial moment, protected herself? Or do they believe she is a cold-blooded killer telling convenient lies?

“This isn’t self-defense,” Krauss told the jury. “The evidence will show the defendant, Nicole Addimando, pressed the barrel of the gun on Christopher Grover’s temple when he was asleep lying on his couch, and she shot and killed him in his sleep. That is why at the end of this case, based on the evidence and based on the law, I will ask you to return a verdict of guilty of murder in the second degree.”

Krauss was assigned to Nikki’s case in November 2017. She spent six months, she told me, “living through Nikki’s life,” “investigating … as if she was my victim.” “Individuals around me were saying, ‘It’s so clear she’s full of shit… .’ I said, ‘I need to keep an open mind to the possibility there is truth to something she’s saying.” Krauss decided that Nikki’s narrative of traumatic events was “inconsistent.” The narrative was complicated by Nikki’s disclosures that Chris was not her only abuser.

In interviews, documents, court transcripts, therapy records, and other evidence gathered, Nikki recounted abuse or mistreatment by four men, including a childhood rape, assault by a maintenance worker, an exploitative relationship with a police officer, and the physical and sexual abuse by Chris. Nikki’s involvement with three of these men overlapped at some point between 2010 and 2012, and her memory of the details is muddled. I have attempted to construct the likeliest timeline of events using information collected by both the defense and prosecution and Nikki’s testimony in court, as well as my own reporting and interviews.

In 1992, Nikki, age four, moved with her mother, father, and sister to the Poughkeepsie area. Three-year-old Caitlin Sanford lived across the street in a house that belonged to her mother’s boyfriend’s father, a man she called Uncle Butch. Sanford and Nikki became friends. When Nikki was five, the girls had their first sleepover, cuddled together in Sanford’s bed. They were awoken by Butch. He grabbed Nikki by her calves and slid her, on her stomach, to the end of the mattress. Her small body had only heated the top half of the sheets. The bottom was cold. “Such a big girl, at your first sleepover,” he whispered as he held her down. Then he raped her. Sanford, whom Butch had been abusing since she was a toddler, lay motionless, her eyes shut. Nikki recalled the chilled sheet and the splitting pain of penetration. She woke to the smell of frying bacon and the damp mattress beneath her; Sanford had wet the bed.

According to interviews with Michelle Horton and Sarah Caprioli, Nikki’s mom Belinda found blood in her daughter’s underwear and took her to the pediatrician, who attributed her broken hymen to gymnastics practice. Nikki turned from a free spirit, climbing trees and rescuing sickly birds, to a spooked, jittery child terrified of being separated from her mother. She insisted on wearing a locket with Belinda’s picture inside whenever they were apart. But Belinda didn’t press. In one journal entry, Nikki wrote in pink crayon: “I don’t like unkle Butch anymore.” In another, in cursive pencil: “I have secrets. she won’t care or belive me.”

A 2019 study at an Oregon prison found that prior to adulthood, more than 80% of the incarcerated women had been abused emotionally, almost 70% had been abused physically, and 75% had been abused sexually. A 2015 report by the Human Rights Project for Girls revealed the “abuse to prison pipeline,” a term for the epidemic rates of abuse histories in girls, and disproportionately girls of color, who enter the justice system. In some cases, according to the report, girls were “punished as perpetrators rather than served and supported as victims and survivors.”

For decades, Sanford and Nikki never discussed their shared trauma. But when Nikki arrived at the Dutchess County Jail, she learned that days before, Sanford, heavily pregnant and sober after years of heroin addiction and homelessness, had been released after serving seven months for shoplifting. Had their time overlapped, they would have shared a cell wall. The women had fallen out of touch, but in March 2017, when Sanford’s mugshot went online after an arrest, Nikki took a screenshot and emailed it to Caprioli. “It fucks with me when she’s arrested,” she wrote. “I hate him. He destroyed our chance at a normal life. At age 5.”

On Nikki’s first night in jail, she wrote a letter to her old friend: “Cait, this is important. I know it’s hard to re-live, trust me, I know. But do you remember the first time I slept over? We shared a bed. I know your eyes were closed but I can still picture your eyelids fluttering. Did you peek? Did you see Butch? Did he do it to you, too? If you saw what he did to me, and he did it to you, too, please, break the silence. I love you, always.”

Months later, Sanford visited Nikki in jail. Nikki told her the DA doubted the veracity of her abuse history, including the rape by Butch. “I said, ‘They’re in for a fuckin’ surprise,’” Sanford told me last year, smoking a cigarette on her porch as her children napped. With her newborn in tow, she went to meet the DA’s investigator and recounted what Butch had done. “Not out of some blind allegiance but because it’s the truth,” Sanford told me. She suspected her existence as a child witness was the only reason Krauss had never publicly questioned the early abuse.

Nikki and Chris met in late 2008 when they were both gymnastics coaches in Poughkeepsie. She was 19; he was 21. Their friendship deepened into a romance. Nikki testified that they waited a year to consummate the relationship because she was scared of sex, which caused her to flash back to her childhood rape. Chris, initially compassionate, grew frustrated; she asked him to stop often. One night, she woke to him finishing inside her. Soon, he always kept going, even when she protested.

At the time, Nikki was living with her mother, then separated from her husband, in an apartment complex Belinda managed. Ashamed, Nikki confessed to Belinda that Chris liked “weird things” and that she never felt pleasure during sex. Belinda was fond of Chris. She had often teased Nikki for being “a prude” with “hang-ups.” When Nikki was a teenager, Belinda had once acknowledged her suspicions Butch had abused her daughter. The two never spoke of it again. According to Horton, Belinda, who had been date-raped as a teenager and beaten by a boyfriend when she was younger, considered sexual and domestic violence to be “the risks when you date.” Belinda advised Nikki to keep trying to satisfy Chris. Sometimes you had to do things you didn’t like, she told her. (Belinda died in January 2019.)

According to Horton, Belinda also introduced Nikki to a maintenance worker for the apartment complex. Belinda was friendly with the man, and the two sometimes shared tequila shots at her place. One afternoon, around 2010, Nikki recalled when she was home alone, the worker stopped by to repair some tiling. Nikki says he followed her to her room and tried to kiss her. She resisted. He slapped her, pushed her to the bed, and raped her. Afterward, she was furious at herself; she felt she had not fought hard enough.

On the stand, Nikki recalled Chris’ response when she told him about the worker: “‘Is that your excuse for not wanting to have sex with me? You must like it rough.’” She testified he began to spank, strangle, and restrain her. Nikki later testified the worker, who had keys to all the apartments, assaulted her on at least one other occasion, of which she had only fragmented memories.

“When Nikki and I first talked about this, the impression she gave was it happened regularly,” Caprioli told me. “Traumatic memory is very fragmented. As we worked together, it became clear maybe two or three assaults were from [the maintenance worker], but she would get triggered [when she saw him].”

During this time, people who knew Nikki expressed concern as she grew increasingly distressed, slept and ate less, and exhibited a cascade of injuries. In photos taken in 2011 and 2012, Nikki has a constellation of bruises and bite marks on her body that are similar to photos taken after two separate rapes and beatings in 2014 that were documented by forensic nurses. In records of the 2014 exams, Chris was named as the perpetrator. Did Nikki deny the intensity of the early abuse by Chris or conflate overlapping abuse by Chris and the worker? At trial, the defense’s forensic psychologist, Dr. Dawn Hughes, an authority on trauma, testified she thought Nikki had “absolutely” done “what many women in violent relationships do, not wanting to identify the perpetrator of abuse as her partner.” Overlapping abusive incidents, Hughes said, could “blend together.” Hughes conducted 10 psychological tests, a clinical interview, and 16 hours of evaluation and determined Nikki was a reliable reporter who tended to minimize, not exaggerate, the abuse she had endured.

In 2011, Nikki was studying early childhood education and dating Chris while they both taught gymnastics at the same studio. Around this time, the father of a young gymnast noticed Nikki, then his daughter’s coach, was often visibly hurt. The man, a police officer, confronted Nikki. After much urging, Nikki admitted she was being assaulted but refused to divulge the identity of her assailant.

In what appeared to be a protective gesture, the officer eventually invited Nikki to stay with him as a caretaker for his child. Nikki left her mother’s apartment to live with the officer and his wife, who referred to her as their “eldest daughter.” She continued to date Chris. She thought of the officer as a “father,” she testified, but he began to approach her at night. “It turned inappropriate. He had sex with me.”

“Well, did you have sex back with him?” Krauss asked.

“I didn’t stop him.”

“She was 22, he was 45, and he was a police officer,” Kostyal-Larrier, the domestic violence expert who consulted on Nikki’s case, told me. “What kind of skills, experience, and training do you have that you take a trauma victim into your home and start a relationship with her while holding basic needs — food, shelter, safety — over her head? He exploited her, no different than any other predator.” (The officer did not respond to requests for comment.)

At trial, Krauss characterized the officer as Nikki’s “paramour” and their interactions as an “affair.” The relationship between Nikki and the officer, Krauss said, was further proof Nikki was never abused by Chris. After all, would an abuser let her move in with another man? And would an abused woman have sex outside of her relationship, the revelation of which would surely lead to great bodily harm?

The prosecution’s expert witness, a psychologist named Dr. Stuart Kirschner, said a typical batterer holds his victim hostage. “If he’s a batterer, for lack of a better term, he’s putting her on a really long leash,” Kirschner testified. And a typical victim would not send “condescending” texts to her batterer, as the prosecution showed that Nikki had once done in 2017, during an argument with Chris. By sending such texts, “she’s inviting abuse,” Kirschner testified. Nikki was “walking right into it … it’s provocative.”

In 2012, while living with the officer and dating Chris, Nikki began to have panic attacks. That June, a friend sought services from a local domestic violence agency. Nikki was “very reluctant to tell her story,” the friend wrote in an email to a social worker. The friend, who had observed injuries and a change in Nikki’s behavior, took her to the ER, where she was found to be dehydrated, undernourished, and pregnant. “She is a shell of the person she used to be.”

Nikki, then 23, told Chris about the pregnancy. They moved in together, painted a nursery nook, and assembled a crib. Those months, Nikki testified, were a reprieve during which Chris was “excited and gentle.” She gave birth to Ben in December 2012.

When Nikki was about six weeks postpartum, Chris began to demand sex. Nikki refused. “He grabbed the right side of my face and hit the left side of my face into the doorframe and had sex with me anyway,” she testified. “He said I was a good mom, but he had needs too.” In a snapshot from the time, admitted into evidence, Nikki and baby Ben lie beneath a white blanket, their faces close. A flat, reddish-purple mark runs across Nikki’s left temple.

The snapshot was one of Nikki’s many photographs and documents of abuse entered into evidence. But for Krauss, these items proved nothing. When I asked Krauss about the pictures — of burns on Nikki’s chest and labia and inner thighs, of large red and purple bruises on her cheek and neck — she answered: “You cannot rule out the possibility it was self-inflicted. You cannot rule out the possibility it was foreplay with any one of her other sexual partners. You cannot rule out the possibility she introduced that type of foreplay with her partners.”

After all, was it plausible, Krauss had asked the jury, for one woman to have been brutalized not only by her boyfriend but by others, too, and, on top of that, for her to not remember all the details of these many assaults?

In fact, more than 40 years of research and multiple studies show that abuse begets abuse and that sexual victimization in childhood raises the risk of sexual revictimization in adulthood by up to three times. More than 130 years of research has shown that trauma memories are typically fragmentary, disorganized, and nonverbal in nature. Traumatic stress, it has been shown, tends to enhance the storage of “central details” — those to which a person’s brain attached attention or emotional significance as the event unfolded — like smells or body sensations but not “peripheral details,” like timing or chronology. From an evolutionary standpoint, sensory details might warn of danger later on and allow a person to avoid it while recalling a precise timeline would be useless.

Every man in her life, Krauss told the jury, “they’re all in some way stalking or abusive to her. Think about that when you examine her credibility.”

“That’s a classic tactic but usually for defense attorneys, not prosecutors,” Jim Hopper, a Harvard Medical School teaching associate and expert on the neurobiology of trauma and sexual assault, told me. “Victims are traumatized, beaten down, and have spotty memories. Then defense attorneys point to those very effects to deny the assault happened or, short of that, to blame victims for it … the crime’s impacts on the victim are weaponized to secure the perpetrator’s impunity.”

The criminal justice system — police, lawyers, judges, and juries — often demands a perfect recounting of events that, by their traumatic nature, can make a perfect accounting impossible. In so doing, these authorities may equate normal human responses to trauma with lying.

“The worst way to tell a story is through direct and cross-examination,” Goodmark, the law professor, told me. “On direct, a witness has to be responsive to questions and can’t give the entire context. During cross, which is designed to make you look like an idiot, trauma victims have issues with storytelling.”

Nikki testified that Chris told her if she exposed his sexual attacks, he would tell people she liked it: “He said I would look like a whore.” She feared she would be castigated and faulted, her past exposed, degrading images publicized. At her trial, this is exactly what happened.

On the morning of Nikki’s first day of testimony, March 25, 2019, she sat flanked by her attorneys, trembling uncontrollably. She was called to the stand, sworn in, and seated before the courtroom.

Ingrassia stood at a podium, facing Nikki. She stated her name, date of birth, and educational background. As she said the names and ages of her children, she briefly broke into tears. Then she straightened, grew resolute, and began to answer Ingrassia’s questions. He walked her through the evidence, beamed onto large screens, visible to the jury and spectators. For each photograph, Nikki recounted the cause of her injuries: slammed into a counter, a cabinet, a floor; whipped; kicked; backhanded. An enormous image of her labia, covered in lesions, was broadcast to the court: the result, she said, eyes downcast, of an attack while she was pregnant with Faye. She had been cooking eggs for Ben, who was asleep, when Chris demanded she make some for him, too. “Yes, sir,” she said sarcastically.

“He moved the pan of eggs to the back left burner, and he took the spoon out of my hand.”

“And what happened next after Mr. Grover took the spoon out of your hand?”

“He grabbed my wrist with his left hand and he held the spoon to the flame. … He held it to my skin, and he held it there until the heat ran out.”

Ingrassia then showed the court Caprioli’s screenshots from Pornhub: Nikki naked, bound, hunched, restrained, and gagged.

“Did you consent to that being done to you, Nikki?” Ingrassia asked.

“No.”

Ingrassia asked Nikki to tell him what happened on the night of September 27 leading into the early morning of September 28, 2017.

After the CPS visit, Nikki testified, Chris went to work, and Ben and Faye watched Free Willy. She took them to the park, put them to bed, and sat on the couch, waiting. Throughout the day, she testified, Chris was acting “really calm” and calling her “hun,” which was unusual. She hoped, she testified, that “maybe now that people are watching, this would be the thing that would make him change.” But when Chris returned, she understood that he planned to kill her. The first sign, she recalled, was the “look on his face.” She suggested that they separate temporarily.

In response, Nikki testified, Chris walked to the bedroom and removed his pistol from its box. He cleaned it. He put in several bullets and handed her one to put in, too. Police investigators later extracted deleted searches he made on his phone around 11:30 that night: “When shoot her will they know she was asleep when examining her? Will they know she was asleep when shot? Part of brain to shoot in suicide.”

He showed her diagrams of the human brain, she testified. He pointed out the place to shoot to kill, as well as the place that would allow her to live but without speech or memory. “Wouldn’t that be convenient,” he said. She carried her phone to the bathroom and turned on the shower. He followed her, remarked that shooting her there would cause an echo, and took the phone. Afterward, he sexually assaulted her in the living room. Then she went to soothe Faye, who was crying.

When Nikki returned, she recalled Chris told her to lay atop him. When she believed he was asleep and tried to slip away, he started and pulled the gun from the couch. Nikki pushed him and jumped off, sliding on a rug. The gun fell to the ground. Nikki grabbed it and pointed it at Chris. He asked her if she felt powerful. She did not answer. They were positioned between their children’s room and the door. She could not safely carry Ben and Faye away. She would not leave without them.

“He said, ‘You won’t do it,’” Nikki told the jury. “He says, ‘Here’s what you’re gonna do. You’re gonna give me the gun. I’m gonna kill you. I’m gonna kill myself. And then your kids will have no one.’ As soon as he said he’s gonna kill me and himself and my kids are gonna have no one, I took one step and I lunged and I pulled the trigger.”

“When you pulled the trigger, what were you thinking?” Ingrassia asked.

“I was thinking if it didn’t go off, I was gonna be dead anyway.”

“How were you feeling at that moment?”

“Like I had nowhere else to go.”

Image: Hokyoung Kim

Krauss began her cross-examination. When Nikki and Chris first started dating, Krauss said, Chris was “patient with you sexually” and “very concerned about you enjoying sex. Would that be correct?”

“He used to tell me he was going to make me like it.”

“The things that attracted you to Mr. Grover when you met him and you first started dating, you would tell people he was very kind. Isn’t that accurate?”

“He was.”

“And that he was very caring. Isn’t that accurate?”

“He was.”

Chris was a “goofy” kid, according to Krauss. She presented a photograph of him wearing a pink tutu for a breast cancer fundraiser. There were a multitude of reasons Chris was an unlikely batterer and Nikki was no victim, Krauss argued during cross-examination: Chris didn’t object to Nikki having a home birth with Faye. Chris “primarily did the food shopping.” Nikki kept an “immaculate” vegetarian household and wanted to buy “as many organic foods as possible,” even on a “tight budget,” and Chris never said to her, “You know what, I miss a good hamburger.” Chris allowed Nikki to keep the slim profits, which he called her “play money,” from taking baby portraits and wedding pictures and from her baby bootie business, which she made in her “pretty little sewing room.” “No one prohibited” Nikki from going to therapy. Nikki had “quite the freedom during the day with her mommy friends.” In 2013, Nikki made Chris a sweet card. In 2014, she made another. In 2017, in the days leading up to the killing, during a text-message argument about childcare duties, Nikki had called Chris “an asshole manchild” and “corrected his spelling.” Chris loved his mother, father, brother, and kids; and he was much loved, too. When Nikki was pregnant with Ben, Krauss said, Chris was “very excited” to become a father.

“When you were pregnant with Faye, he was equally excited,” Krauss continued.

Nikki frowned. “He put a burning spoon in my vagina when I was pregnant with Faye,” she said. “Things were very different.”

“The burning spoon incident, you said, was as a result of … a snark comment to him,” Krauss replied.

***

“We were convinced Nikki was seriously and severely abused,” Ostrer later reflected to me. “We did the best we could to present that to the jury, but we were challenged by some evidentiary rulings that prevented us from putting what we believed was some very persuasive evidence before the jury.”

Ostrer and Ingrassia were able to show the jury certain pieces of evidence and argue Nikki was being hurt. However, Krauss’ motions and Judge McLoughlin’s rulings meant the defense was hampered in their ability to tie the assaults to Chris. The forensic nurse examiner was not allowed to testify to the fact Nikki had named Chris as the perpetrator of assaults on the grounds of hearsay. And the Pornhub screenshots shown to the jury were scrubbed of the surrounding text, including the channel name, which included Chris’ surname, as well as a bio of a 29-year-old male with Chris’ main hobbies. Jurors also never saw the image captions: “4 hours of toys and torture tonight. bitch begging for mercy.” They saw only floating images of Nikki, naked and bound.

The links between Chris and the Pornhub material were not shown because they could not be “authenticated,” McLoughlin said in court proceedings. This might have been done through Pornhub records, but neither side obtained any. Krauss and Gerry both told me they had subpoenaed Pornhub but could not remember where they sent the document and never received a response. Ostrer and Ingrassia attempted to subpoena Pornhub weeks before trial, but, bewildered by the corporation’s offshore status, sent the order to an address in Cyprus; Pornhub’s U.S. legal contact is in Florida. After four months of inquiries, Pornhub provided me with a statement that said the corporation has “always been cooperative with authorities for investigations and is willing to assist them in any capacity.”

There was another file of Pornhub images that never made it to court. The file belonged to Jason Ruscillo, a detective from nearby Hyde Park, where Nikki and Chris lived from 2013 to early 2017. In November 2015, Caprioli approached Ruscillo and communicated to him that images of Nikki had been uploaded to Pornhub without her consent. Ruscillo began following Chris’s account and kept a file of his investigation. He met with Nikki and offered to arrest Chris if she signed a deposition, but she declined. In an email to department personnel, Ruscillo identified Nikki’s situation as a “high risk domestic” and wrote that Nikki, “the victim,” was “extremely fearful of her boyfriend” and had refused to sign a deposition “in fear for her safety.”

In 2017, after the shooting, a CPS worker approached Ruscillo. According to her log, he stated that “he took screenshots of several photos of the mother and father engaged in various sex acts and compiled them on a disk for the DA’s office.” But at trial two years later, Ruscillo testified that during his Pornhub investigation, he had never seen a man with the defendant. All of the screenshots shown in court had been taken by Caprioli. Krauss later used the fact that no evidence showed Chris actively abusing Nikki to support her contention Nikki was not abused by Chris.

“If Chris Grover were researching pornography, violent pornography to imitate it, why isn’t he in any of these photographs?” Krauss said during her summations. “If Chris Grover were involved in this and it wasn’t consensual, you would have seen Chris Grover in one of these pictures.”

When I inquired after Nikki’s trial, Krauss said that both the defense and the prosecution had copies of Ruscillo’s file, but Ingrassia and Ostrer said they never received anything. (Ruscillo did not respond to requests for comment.)

Then there was potential evidence that was not pursued by the defense or the prosecution. The jurors had learned Nikki had written an incriminating text on August 16, 2017: “I haven’t figured out how to kill him without being caught so I’m still here,” followed by an “eek” emoji. The message was discovered by police when they performed a data extraction, but they only recovered a portion of the full conversation, so the larger context of the message was missing. The recipient, a friend of Nikki’s, saved the original messages on her phone. I acquired them. In an hourlong text conversation, the two mothers moved on immediately from the message. “I didn’t think one single thing of it,” Nikki’s friend told me. “If I had, I would have … expressed concern.” They continued discussing the challenges of parenting and partnership. Nikki told her friend about how Chris’ family loved the children, how lucky and happy Ben and Faye were.

“Hence why I’m still here … just trying to live it out.”

“But you need to be safe.”

“But my kids also need to have a good life. And a home and family and be provided for. If I can hang on till they’re both in school. Then I can work. And it’ll be different.”

Until then, Nikki texted, she would not leave Chris. She told her friend she had tried to do so a few weeks earlier, and the attempt “backfired … when will I learn lol.” She feared that if she reported Chris and he went to prison, his infuriated family would take the children, and she’d be unable to afford a court battle. “No one will believe it. Everyone loves him.”

After the killing, Nikki also attempted to act in what she thought were her children’s best interests. She refused to put forth some elements that might have been beneficial to her because in so doing, she would have had to allow the DA’s team access to Ben and Faye. Chief among these potentially helpful facts were revelations the children had not always been asleep during the attacks, as Nikki had long believed.

The court did not hear that during the first five months of contact visits at the jail, the children examined their mother’s body, checking for “boo-boos,” according to notes made by Dr. David Crenshaw, clinical director at The Children’s Home of Poughkeepsie, who facilitated these visits. They eventually stopped checking: Nikki has not had any injuries since September 28, 2017.

Crenshaw also wrote that Ben and Faye separately disclosed to therapists and counselors they had seen their “mommy was hurt” and their dad did things to her while “she kept asking him to stop and he wouldn’t.” The siblings defaced a doll, drawing wounds on her legs and anus. At camp, a year after the killing, Ben sketched a sexualized, violent scene of a naked man lying next to a naked wounded woman. Crenshaw sent a scan to an expert in play therapy who, to provide an impartial assessment, analyzed the picture knowing only the artist’s age. The atypical, disturbing image demonstrated that the child had likely “experienced or witnessed explicit sexual contact,” the expert wrote. “The overall picture suggests chaos.”

Throughout the trial, Krauss always returned to her declaration that Chris was asleep when Nikki killed him, which meant that even if Nikki had told the truth about everything else, she had still lied about the exact moment of the shooting. However, the state medical examiner testified it is impossible to ascertain if a person was asleep or awake at the time of death. And the state’s DNA expert testified that Nikki had likely held the gun so briefly she hadn’t left a reliable trace; Chris, the expert said, was the “major contributor” of genetic material. However, by saying that Chris was asleep, Krauss was more able to traverse the issues of imminence and justification at the heart of the self-defense statute. And she created doubt.

“If the jury believed he was sleeping, then they believed [Nikki] was lying,” Ostrer told me.

“If he was asleep, and if what she says happened that night was not truthful, then everything going backward falls apart as well,” Krauss told me.

Ostrer and Ingrassia struggled to demonstrate to the jury the long-proven and repeated patterns of domestic and sexual violence and to educate them on the complexities of coercive control. They both told me they were “surprised” at how Krauss used Nikki’s sexual history to “shame” and “discredit” her. Ingrassia was hesitant to criticize his own work. Ostrer was more willing: “We obviously needed to have a different mindset or convey that to the jury,” he said.

Image: Hokyoung Kim

At jury selection, anyone who acknowledged a history of abuse was removed from the pool, Ostrer and Ingrassia pointed out. “There were a lot of complicating facts in this case that occurred years before the shooting that I think made the case maybe a little more difficult for a jury to comprehend without having those experiences,” Ingrassia said. “The way we look at these cases is a homicide case first and foremost … it had extreme elements and undercurrents and flavors … of domestic violence but at the same time, first and foremost, that’s what it was.”

“You can take the best trial attorneys in the world, and if the lens of understanding domestic violence and sexual violence is not there, it can have catastrophic effects,” Kostyal-Larrier told me. “If it’s looked at as any other murder trial, then you will absolutely miss how you got there to begin with.”

Ingrassia and Ostrer positioned Addimando as a piteous woman upon whom horrors were heaped. They focused on their many witnesses, the medical professionals, and the photographic evidence — especially images of Nikki’s sexual abuse. “You want to talk about making things worse for a woman?” Mary Anne Franks, a professor of law at the University of Miami School of Law, asked me. “The moment sexuality is involved, it changes people’s minds. It does something to their brain.”

The legal system, too, has long bolstered the myth a woman’s engagement — willing or not — in sexual acts is an indicator of her truthfulness. A foundational U.S. legal treatise, Wigmore on Evidence, counsels that “chastity may have a direct connection to veracity.” Until the 1980s, when a woman claimed rape, it was common to parade before the court witnesses to her promiscuity — and thereby challenge her credibility. Spousal rape was legal in some states until 1993, and most states still have exemptions that obstruct the prosecution of rape within a marriage. From 2017 to 2019, a Minnesota woman fought to change the law when she discovered a loophole barred her from pressing charges against her husband, who videotaped himself raping her, because the two had a prior “voluntary relationship.”

In deluging the jury with evidence of so much abuse, Ingrassia and Ostrer also confronted an entrenched human propensity to blame victims — especially sexual assault victims. Multiple studies have shown victim-blaming may increase when the victim and perpetrator are romantically linked.

On April 12, 2019, after four days of deliberations, the jury found Nikki guilty of second-degree murder and illegal weapons possession. She was handcuffed and returned to jail to await sentencing.

The jurors were ushered out, refusing to speak with reporters. Some months later, I tracked most of them down. Two spoke off the record and expressed confidence the justice system worked well, and the forewoman sent me a short email: “Each juror took the case seriously, listened attentively, inspected the evidence in detail, and reviewed the law as read by the judge. I am very grateful to live in a country that allows for a jury trial.”

A week later, I walked, unannounced, into a fourth juror’s office and introduced myself as a reporter covering the trial. “We just didn’t buy her story,” she said. “We didn’t discount that, yeah, she had bruises, the whole burning thing where, yikes! But you had the tools to leave, so why did you kill him in his sleep?” Krauss had told the jury Nikki could have gotten out because “she had the car, she had her debit card, gas, money, children, places to go…options.”

Why did the juror think Chris was sleeping, considering the testimony of the medical examiner, who said such a thing was impossible to prove? “None of it in her little timeline, none of it made sense at all,” the juror said.

Did the juror believe Chris had abused Nikki? “We believed she was abused and possibly rough sex,” she said. “I think [Chris] may have hit, burned, denigrated her. Rape. Maybe they’re in the sex club. But … even though I felt for her, bottom line was, we felt he was sleeping and that she was a master manipulator.”

“She could’ve left that day,” the juror said. She reflected that in her own life, she had stopped drinking alcohol, paid her speeding tickets, and left a boyfriend when he pushed her. “Your life is what you make it. You’re a mom of young kids, and you have to go to prison because of your decisions.”

Why, I asked, would Nikki make the decision to kill her boyfriend?

“That, I can’t figure out…”

Soon after I met with the juror, I interviewed Nikki for the first time at the Dutchess County Jail, where she was awaiting sentencing. She bore little resemblance to the eloquent woman I’d seen on the stand. She struggled to answer my questions or make eye contact. “I’m sorry,” she said in a near whisper, the color drained from her face. “I’m really foggy.” She seemed overwhelmed by the prospect of again verbalizing past events, when the state of New York had argued her own accounts of her most excruciating life experiences were false. “I listened to Chana tell me how it was when it wasn’t that way,” she said. Raw-boned, engulfed in an orange jumpsuit, she sat in her cell all day, reading, drawing, and contemplating how she had gotten there.

She had not reported the abuse while it was happening, she said, because she believed at first “it was kind of normal, and I’m not normal.” In time, she reasoned that because Chris, once her “best friend,” had seemed to change during their relationship, his behavior must be a reflection of her. “If he was that way when I met him, if he held me down and tied me up, I wouldn’t be with him,” she said. Even as the abuse escalated, Chris was well-liked at the gymnastics studio and good with kids. “If he’s only different with me, it must be me,” she recalled thinking. In any case, she had not known how to report the “really fucked up” occurrences that happened in her home. “Who was I supposed to tell, and what was I supposed to say?”

Now, she mainly puzzled over why the criminal justice system had converged to destroy her. “I knew the system was broken, but I thought jurors are human beings,” she said. For that reason, and because she hoped to return to her children, she had testified for days, detailing her greatest humiliations. “I got on that stand, and I finally spoke. It didn’t matter. I wasn’t heard. They didn’t believe me at all.”

In May 2019, weeks after Nikki was convicted, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed into law the Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act (DVSJA), which allows a judge to exercise discretion in sentencing if a claimant can prove the abuse they suffered contributed to their crime. If Nikki were found eligible for the DVSJA, which is retroactive, she would be able to receive as few as five years in prison. The law was applied last September in the case of a woman from the northwestern city of Buffalo. Witnesses saw her boyfriend drag her by the hair, choke her, and punch her and observed her naked with a swollen eye just before she stabbed the man to death. The judge ruled she was not eligible for the DVSJA: The abuse was not “substantial,” he said; the defendant “had options.”

On February 5, 2020, Judge McLoughlin presented the court with his 47-page written DVSJA decision. In it, he stated repeatedly that Nikki had used the battered women’s syndrome defense, a legal approach based on a theory, first articulated in 1984, that explains an abused woman’s actions as the result of a narrow number of “symptoms.” Experts have largely abandoned this method and instead attempt to show the impact of domestic violence on the defendant. “Battered women’s syndrome is a diagnosis that was never made nor proffered as a defense,” Ingrassia told me. “For him to say we put on that defense shows he had a misunderstanding of the evidence before him,” Ostrer added.

McLoughlin denied Nikki relief and cited as his reasoning: Nikki’s “undetermined and inconsistent” abuse history; the “undetermined” “nature of the alleged abusive relationship”; the fact Nikki had a “tremendous amount of advice, assistance, support, and opportunities to escape her alleged abusive situation”; and the fact that on the night of the incident, Chris was “supine.”

Kate Mogulescu, an assistant professor of clinical law at Brooklyn Law School who is working on efforts to implement the DVSJA, told me McLoughlin’s reading of the law was “reliant on misunderstandings, myths, and tropes.” The things the prosecutor and court depended on to determine Nikki’s credibility, Mogulescu said, were “problematic.” “A victim must report to the right people at the right time, have documentation but not too much documentation, and accept assistance in the way that it is offered regardless of the complexity of the situation. … There is no way survivors are going to be able to navigate this.”

Six days later, on February 11, McLoughlin sentenced Nikki to 19 years to life.

“Comments have been made that this verdict would somehow impact domestic violence victims from coming forward,” Krauss told the court. “Well, Judge, shame on those who would make such a statement and shame on them for instilling fear for any real victim to come forward. The system did not fail.”

“It’s clear you’ve been abused by other men,” McLoughlin told Nikki. She may have “reluctantly consented” to “intimate acts you were very uncomfortable with,” he said. “Clearly someone who would make the choices you did is a broken person. … When you boil it all down, it comes to this, you didn’t have to kill him.”

Nikki stood before the room, shackled and shaking visibly. She was permitted to make a statement. “I wish more than anything this ended another way,” she said, through tears. “If it had, I wouldn’t be in this courtroom, but I wouldn’t be alive either, and I wanted to live. … So often we end up dead or where I’m standing. Alive but still not free.”

Throughout it all, every week in room 311 at the Dutchess County Jail, Nikki and her children met, even as they prepared for her to be moved to Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison 45 miles south. Horton and Crenshaw told the kids Nikki’s forthcoming relocation was the “next step toward her coming home.” At the jail, the small family ate Skittles and mini donuts and conjured up an imaginary home in an alternate reality: 560 Together Lane. They crawled beneath the metal table, decorated it with balls of paper and strings of toilet paper, and pretended to be reunited for real, playing out the comforting banalities of domesticity: sleeping, eating, singing. They envisioned living on Together Lane one day and planned a celebration for Nikki’s release. Five-year-old Faye was optimistic, but Ben, seven, was hesitant. He stood in awe of a system that seemed to heap punishments upon them all without cease.

“Who’s more powerful,” he once asked Nikki, when she urged him to remain hopeful. “The people who want you to stay here or the people who want you free?”

A new legal team was working on Nikki’s appeal. Failing that, she could only seek clemency, granted by the governor. When he signed the DVSJA, Cuomo announced that in so doing, “we can help ensure the criminal justice system … empowers vulnerable New Yorkers rather than just putting them behind bars.” In the past nine years in office, however, Cuomo has commuted the sentences of only two women who defended themselves against gender violence — after one had served 17 years and the other 23 years.

I met Krauss at her office in early March. We sat at a dark wood table with a bowl of candies and a vase of yellow roses. The case, Krauss told me, “became all of me.” Nikki had “created this horrible story,” Krauss said, and she was “really grateful the truth came out.” In nearly three decades, she had never given a media interview, but she agreed to talk because she hoped the press would have “the courage to print the truth.”

“The message that’s getting out there is incorrect, and it’s a very scary message,” Krauss said. “It’s instilling fear in other victims to not come forward, that somehow the system failed her and didn’t protect her. I tried to make it clear at the sentencing. There are enormous resources for victims. … Victims have to understand and know that they can come forward and they can leave, and they can be safe. … She just wasn’t a victim.”

Five days later, I met Nikki at Bedford Hills. We sat in a visiting room with violet walls, overlooking dry grass and fences lined with coils of razor wire. A pandemic was hurtling across the globe, and the National Guard had created a “containment zone” around a town 30 miles away. I saw some posted signs but no extra hygiene measures in place. Nikki hadn’t heard much of the news. She mostly sat on her top bunk in a squalid dorm, trying to untangle the past years and understand her current situation.

Within a week, all visitation to the prison would close, and the coronavirus would sweep the facility. By mid-April, Nikki would lose her sense of taste and smell and her pounding head would grow too heavy to lift from her pillow. At the end of the month, a 61-year-old survivor of domestic and sexual violence who had been preparing her DVSJA case from behind bars at Bedford Hills died of Covid-19, the first such fatality of a woman incarcerated in New York. Nikki would recover but would be unable to see Ben and Faye indefinitely; brief daily phone calls would become their only form of contact.

During our March meeting, Nikki wanted to know if there was anything she could have done to make Krauss, the jury, or the judge believe her. Other women inside kept saying she’d been a fool to turn down a plea offer of lesser time. Nikki longed to care for her children, to “go home.” Still, she did not regret having gone to trial. “If I had taken a plea, I would have wondered every single day I served: ‘What if I spoke, what if I was brave?’” she said. “I was not willing to give up the chance to be free, to be with my children. It was the fight for my life all along. It still is.”

Special thanks to deputy editor Sarah Blustain and fact-checker Nina Zweig at Type Investigations for their support of this piece.