This year, as politicians, voting rights advocates, and elections experts call for a sharp increase in the use of mail-in ballots to prevent the spread of Covid-19, many more voters could find, like Romo, that their votes don’t count. That’s because significantly expanding vote-by-mail also expands the universe of ballots that get scrutinized by officials, and past experience shows that more scrutiny means more ballots get discarded, sometimes for good reason but sometimes by mistake.

“Just by the sheer volume — and just assuming there’s a constant error rate — we’re going to get a significant increase in just the number, the absolute number of rejections,” said University of Florida political scientist Michael McDonald, who specializes in U.S. elections. “There are going to be many thousands, if not millions, of people who are going to be having problems with their mail ballots.”

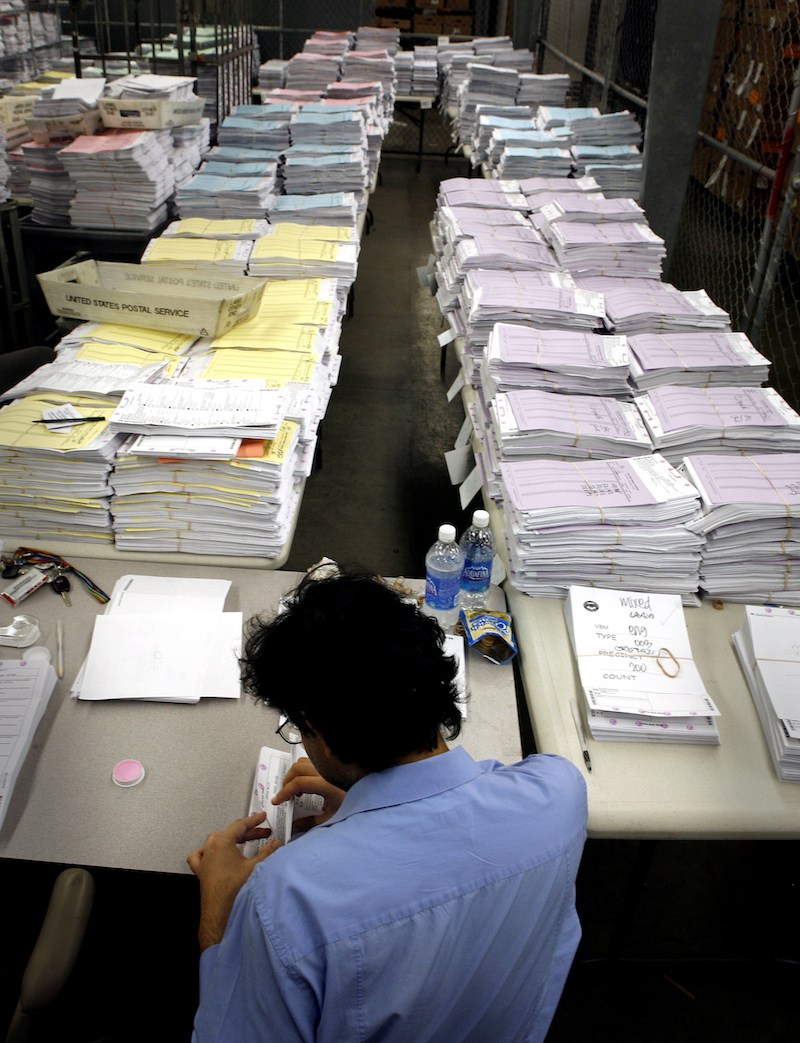

An election worker sorting by-mail ballots in California.Image: Mark Boster/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Inconsistent signature matching rules are just one risk that accompanies voting by mail in the United States. Unlike regular ballots cast at a polling location, ballots cast by mail are inspected before being counted. They can be rejected by election officials for a number of reasons: lateness, errors on the attached form, lack of signature, and a lack of witnesses, among others. Voters who might otherwise have asked a poll worker for help might make mistakes on the ballot they fill out at home, causing their vote not to count.

According to a new calculation by The Intercept and Type Investigations, over 950,000 votes were rejected by officials in the last presidential election, based on data released by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. This includes more than 300,000 domestic mail-in ballots and more than 600,000 provisional ballots cast at the polls. The risk of rejection varies widely by state. In the 2016 election, the mail-in ballot rejection rate in Georgia was roughly 30 times higher than the mail-in rejection rate in Wisconsin. This figure includes both domestic absentee ballots and ballots from military personnel and citizens abroad.

The five states that currently hold all-mail elections — Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington — didn’t count between 0.7 and 0.9 percent of mail-in ballots received. New York, on the other hand, which received far fewer mail-in ballots relative to its voter turnout, didn’t count ballots it received at a rate up to almost eight times higher than those other states.

Some of the most populous states in the country also had the highest ratio of rejected ballots compared to the size of their voting population, the analysis by The Intercept and Type Investigations of rejected ballots in 2016 across all relevant ballot types — provisional, absentee, and overseas military and civilian — found. A recent lawsuit in New York, where 2016 vote-by-mail ballots were rejected at nearly five times the median rate for the country as a whole, shows some of the pitfalls that may await.

The hurdles that accompany vote-by-mail logistics are not insurmountable. The states that vote entirely by mail have carried out elections for years without major problems. Research shows that states where vote-by-mail has expanded have seen a modest increase in voter turnout, and voting rights advocates are unanimous about the benefits of giving voters more options to cast their ballot.But with potentially millions voting by mail for the first time, especially amid the coronavirus pandemic, jurisdictions accustomed to a trickle of mail-in ballots will get a flood. Over half of U.S. states received fewer than 10 percent of their 2018 votes by mail, including populous states like New York and Texas, according to an analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice. Several of the country’s largest jurisdictions will be among the many trying to quickly scale up their vote-by-mail infrastructure to emulate systems that took other states, like Washington, years or even decades to create. Voters who don’t receive absentee ballots in time — like many in Georgia last week — may still show up in person, meaning that the existing in-person infrastructure cannot be abandoned or aggressively consolidated. As the New York Times pointed out, administrators will, in essence, have to conduct two simultaneous elections.

Reducing the risk of valid votes being thrown out will require heroic efforts on the part of election administrators, who will be tasked with reviewing far more votes than ever before. Already, teams of experts and advocates have formed to safeguard the process, but they will need to work quickly, and receive political support, to be successful.

Denise Roberts headed to her Tioga County, New York, polling place early on November 8, 2016, to avoid the lines. But her name wasn’t listed in the poll book. It didn’t make sense, she recalled in an interview with The Intercept and Type Investigations. She had moved to the area several years ago and voted at the same fire station just 12 months before. She even had a paper card from the county Board of Elections confirming that she was registered at her current address.

The poll workers told Roberts that her registration was inactive, and she would have to vote using an affidavit ballot, known in other states as a provisional ballot. Rather than being counted automatically, the ballot would, like Romo’s, be scrutinized after Election Day by elections officials, who would determine whether her vote was legitimate.

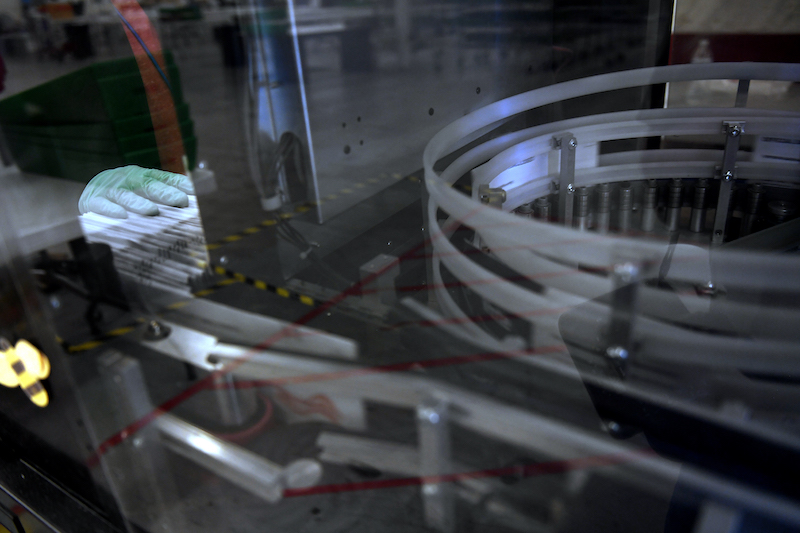

An election worker prepares to load vote-by-mail ballots into a sorting machine at King County Elections in Renton, Washington on March 10, 2020.Image: JASON REDMOND/AFP via Getty Images

Roberts wondered if the fact that she was a black woman in a 95 percent white, rural county had come into play. “It was humiliating,” she said. “I didn’t believe what had just happened.” Then the same thing happened to Roberts’s daughter-in-law Angela, who lived with her. Despite being properly registered at the address where they lived, the Robertses had no confidence that their affidavit ballots would be counted. Their suspicions were correct.

The Robertses were later deposed in a voting rights lawsuit that John Powers of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, who represented the plaintiffs, called a “canary in the coal mine” for efforts to expand vote-by-mail in the 2020 election. It revolved around the state’s practice of moving people from an “active” registration list to an “inactive” registration list if certain trigger events occurred. One of those events, crucially, is the return of a single piece of election mail as undeliverable.

At the time, the names of “inactive” registrants in New York weren’t sent to the polling place, and these voters were required to cast provisional ballots. This year, they will be provided to poll workers, per a federal court order, but they will still be required to vote provisionally. That means their votes can be rejected due to errors on the ballot or, occasionally, for no clear reason whatsoever. That was the case with the Robertses, whom officials ultimately admitted had been wrongly disenfranchised due to administrative error. The state’s apology was little comfort for Denise Roberts. “I never expected to experience that my voting rights would be taken away by somebody making a decision,” she said.

Marc Meredith, a University of Pennsylvania political scientist who was an expert witness in the case, calculated at the time that New York had a higher rate of rejected provisional ballots compared to the total number of votes than any other state in the U.S. In addition to tens of thousands of people who relocated within the state, in 2016 roughly 45,000 people cast provisional ballots with their registered addresses, suggesting that they had very likely been improperly deemed “inactive” by the state. Tens of thousands of erroneously deactivated voters were thus funneled into an administrative process in which their votes had a good chance of being discarded. In the 2016 general election, only about 51 percent of the provisional ballots cast in New York were ultimately counted.

Relying on undeliverable mail as a way to maintain accurate address lists can be highly problematic. “We have uncovered, over the course of time, significant issues with the consistency of the information that we get from the post office vis-à-vis who’s at this location and who is not at the location,” testified New York City Board of Elections Executive Director Michael Ryan, the top election official in the city. He told lawyers in the case that quotidian problems can have disastrous results, especially in urban areas: If the center lock is broken in the bank of mailboxes of a large apartment building, for instance, the postal worker won’t be able to leave the mail there, causing everyone in the building to become “inactive” unless they go to the post office in person to collect their mail within 14 days.

“Quite frankly, it has caused us to have little faith in the overall reliability of the quality of information that we get from the post office,” Ryan said, adding that the moves to inactive status disproportionately affect people who live in multiunit buildings. Ryan complained that to avoid this “unintended consequence” of New York’s registration laws, he tries not to send mailings unless they are critical. Missing virtually any piece of mail — even a letter confirming a voter has been moved back to “active” status — can cause a voter to be kicked off the “active” list if the post office cannot deliver it. In her opinion, Judge Alison Nathan found “the central proxy that the State uses to determine whether a voter has moved has serious problems with its reliability.”

New York’s mail delivery problems bode poorly for the state’s ability to ramp up vote-by-mail in time for the November election, experts said. Some voters won’t receive mail-in ballots to which they are entitled, and other ballots will likely end up in the wrong voters’ hands.

The same is true for other states unaccustomed to regularly interacting with voters that way, said Charles Stewart III, an elections expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “The vote-by-mail states are doing a lot of mail business with their voters; they’re sending a ballot every election, they’re sending voter information guides every election, they’re interacting with their votes a lot by mail. And one consequence of that is that their voter rolls are very clean,” he said. “Whereas the purpose of the voter roll in New York is not to do a lot of mail transactions with voters, that’s not why it was constructed. And so you’re suddenly putting a burden on the voter list that it wasn’t designed to bear.”

This machine, used in Colorado, can automatically verify some signatures, but not all of them. And many election offices don't have such time-saving machines.Image: Joe Amon/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Mail-in and provisional ballots can be rejected for legitimate reasons, such as a would-be voter lacking eligibility. They can also be rejected for more contentious reasons, many of which involve human error: failing to sign the ballot, failing to have a witness where required, or making a mistake on the form that goes alongside the ballot.

The most common reason in 2016 was the one that invalidated Maria Fallon Romo’s ballot: a perceived mismatch in the signature between the ballot and the voter registration, according to a report by the Election Assistance Commission. In many states, the criteria used to reject those ballots are poorly defined and left to the discretion of untrained election workers.

It is a fraught effort: Signatures can vary depending on age, health, disability, writing utensil, and even noise and stress levels. Though signature matching helps election officials confirm the identity of someone casting a ballot from home, rather than from a polling place, election experts said the effectiveness — and accuracy — of signature checks vary widely by state. Some states, like Colorado, have detailed guidance on how to examine a voter’s signature, based on scientific principles of forensic document examination. Other states do not. Research has shown that laypeople are three and a half times more likely than trained forensic document examiners to incorrectly identify signatures as nonmatching. Laypeople are also more likely to reject authentic signatures than to make the opposite error and accept forged signatures.

Research has also shown that voters of color and language-minority voters are more likely to have their mail-in ballots rejected by elections officials. Voters whose native language uses non-Latin characters display greater signature variability, which officials might interpret as attempted forgery. Voters of color might also have less information about how to cast a valid ballot; a 2014 study found that election officials were less likely to answer Latinx voters’ questions compared to white voters’ questions.

- In the 2016 general election, only about 51 percent of the provisional ballots cast in New York were ultimately counted.

In recent years, the lax standards around signature matching have been subject to repeated legal challenges. In 2019, the 11th Circuit Court lambasted Florida’s signature-matching law on the grounds that it subjected vote-by-mail and provisional voters to “the risk of disenfranchisement.” The state lacked uniform standards for what counted as a signature match and didn’t require any training or qualifications for ballot inspectors. By allowing each county to apply its own procedures, the court’s majority wrote, Florida is “virtually guaranteeing a crazy quilt of enforcement.” Florida has since enacted legislation requiring formal signature-matching training for elections supervisors as part of a reform package.

Florida has an appeal process to defend against unfairly discarded ballots, but notifications for rejected ballots come far too late to take part in it. The problem can affect even sophisticated voters like former Rep. Patrick Murphy, D-Fla., whose ballot was rejected and who didn’t get a chance to appeal. The court therefore found the appeals process to be “illusory” in some circumstances.

Experts say that’s why it’s better to count votes the first time around. “People aren’t going to go back after an election to fight for their ballot to count given everything they have going on in their lives and given the fact that the election was already decided,” Powers said. “They have too much on their plate to play election lawyer and track this down when it seems like an academic exercise.”

The National Vote at Home Institute, an organization that advocates for policy changes to make it easier to vote by mail, encourages all states to adopt modern, flexible, and voter-friendly appeals processes.

“There are risks on both sides here,” said Stewart, the elections expert at MIT. “I think the right way to think about this is to think about the risks on both sides and to try to mitigate both the health risks of voting in person and to mitigate the risks of having ballots rejected.”

In March, as deaths from the Covid-19 pandemic began to mount, election officials and advocates gathered by phone to plot a solution. Clearly, many thousands of people would not want to vote in person in upcoming primaries or in November’s general election, but most states weren’t ready for a huge surge in vote-by-mail. For Amber McReynolds, CEO of the National Vote at Home Institute, this is a critical moment. Her group has developed a plan calling for centralized or regionalized mail operations, tighter coordination with the post office, and improved signature verification processes.

Election officials are working quickly, she said: “They’re trying to find solutions to very difficult problems. [But] in many ways, they have one hand tied behind their back because of outdated laws and policies.”

Expanding vote-by-mail is popular among voters from both parties, and both Republican and Democratic governors and secretaries of state have mailed millions of voters absentee ballot applications, allowing them to apply to vote by mail in the primaries. It would not only reduce the risk of disease transmission between voters, but it could also help protect poll workers, 56 percent of whom were older than 60 in the 2016 election, according to a survey of over half of poll workers nationwide, and many of whom interact with hundreds of people on Election Day. Apparent elections-related transmission of the virus has been observed in Wisconsin and Florida after they held in-person elections this spring.

Many states are already planning for a large vote-by-mail component in November and the first half of 2020 has seen a flurry of legislative activity around the moves. In some states, voters need a valid excuse for voting by mail, though in some cases the requirement is being waived in light of the pandemic. (Seven Republican-led states have expanded no-excuse vote-by-mail for elderly voters only, a demographic that often favors Republicans.) But, the charge for a massive increase in voting by mail isn’t being led by lawmakers themselves, McReynolds said. “Voters are choosing in exponential numbers to sign up to get a ballot at home this year,” she said. Officials need to be prepared.

Kim Wyman, Washington’s Republican secretary of state, and her elections director have spoken with top election officials from all 50 states and Puerto Rico in order to share lessons from Washington’s successful all-mail elections. The Center for Tech and Civic Life, Center for Civic Design, Brennan Center, National Vote at Home Institute, and other nongovernmental organizations drew up detailed road maps for election administrators to scale up vote-by-mail in their states. Academics from Stanford and MIT launched a joint project to identify and disseminate best practices. And task forces of experts and political functionaries are putting forward plans, hosting webinars, and convening conference calls.

Many of the plans involve reducing existing barriers to voting by mail, such as the demand that voters have an excuse or allowing Covid-19-related excuses and removing the requirements in some states for a witness or notary to sign the ballot. Experts are also calling for less error-prone signature-matching procedures, improved appeal processes, expanded ballot return options, prepaid return postage, and acceptance of ballots postmarked by Election Day. Administrators may be able to implement some of these fixes without changes to state law and within existing budgets, but others may require legislative action, and the apportionment of additional funds.

In April, the Brennan Center for Justice recommended that Congress allocate “at least $4 billion to ensure all elections between now and November are free, fair, safe, and secure.” In March, the center had estimated that prepaid postage alone would cost roughly $500 million. There is scant indication that the Republican-controlled Senate will appropriate anywhere near the amount being requested by Democrats. And if Congress does appropriate that money, the National Vote at Home Institute’s McReynolds is doubtful that it could even be used to fund expanded capacity. State and county budgets have been devastated by the coronavirus pandemic, she said, and in many cases they will need federal relief just to implement the election plans they developed pre-coronavirus, to say nothing of expanding their existing infrastructure.

If and when states receive the money, the supply chain will need to be activated: Companies that print bulk mail for existing vote-by-mail states like Colorado have said they will need financial commitments months in advance of November in order to expand their production capacity. A machine to automatically insert ballots into envelopes can cost up to $1 million, for instance, and vendors won’t purchase extras without guarantees that states will contract them to produce bulk mail. Vendors and officials will need to design and deploy systems to track, monitor, and sort the massive volumes of paper. “This three-month period, we’re really in a critical time,” said McReynolds.

- Some states, like Colorado, have detailed guidance on how to examine a voter’s signature, based on scientific principles of forensic document examination. Other states do not.

There is also the question of whether the underfunded and overworked U.S. Postal Service can handle millions of additional pieces of election mail without errors; though it is not clear yet whether mail services or election administrators were responsible, there were problems this spring when people who requested mail-in ballots in Georgia and several other states did not receive them in time. In Wisconsin, for instance, boxes full of undelivered absentee ballots were discovered after the election, potentially thousands of voters did not receive their ballots in time to vote, and other ballots were mailed but never postmarked, thus potentially becoming invalid.

In an email, a spokesperson for the U.S. Postal services told The Intercept and Type Investigations that the agency will be ready in November. “The U.S. Mail serves as a secure, efficient and effective means for citizens and campaigns to participate in the electoral process, and the Postal Service is committed to delivering Election Mail in a timely manner,” she wrote. Knowing that Covid-19 will prompt more people to vote by mail, she added, “we are conducting … outreach with state and local election officials and Secretaries of State so that they can make informed decisions and educate the public about what they can expect when using the mail to vote.”

This fall will be a stress test of the U.S. election system, as administrators working with decimated budgets attempt to handle a massive increase in voting by mail while maintaining in-person voting options. With many state legislatures prohibiting officials from processing absentee ballots before Election Day, delays in generating results are likely. There is concern that irregularities and delays could undermine public confidence in the outcome of the election, a problem made worse by Trumpian allegations of widespread fraud.

Throwing out too many ballots may be just as dangerous as throwing out too few, experts said. As Marc Meredith noted in the New York lawsuit, “Making potential voters less certain that their ballots will count makes it less likely that they will vote.”