Crusius belonged to one of the new online subcultures that embraces the “Great Replacement,” a conspiracy theory claiming that White people are being selectively “replaced” by non-White immigrants, a gradual “invasion” intended to wipe out White civilization, orchestrated by a cabal of nefarious “globalists” and Jews.

Widely popular among the new generation of White nationalists, the idea is largely credited to a 2012 book of the same name by French conspiracy theorist Renaud Camus, who had coined the term in previous writings. “The great replacement is very simple,” Camus has said. “You have one people, and in the space of a generation you have a different people.” Camus’ thesis quickly spread in White nationalist circles online and was a favorite topic of discussion in far-right online spaces such as 4chan and Reddit. Since then, the idea has served as a throughline linking Tarrant’s anti-Muslim massacre in Christchurch, Bowers’ alleged attack on Jews in Pittsburgh and Crusius’ alleged attack on Latinx people in El Paso with the torch-bearing marchers in Charlottesville.

In the bowels of this online culture are participants who turn terrorism into a game; who “score” brutal attacks according to body count, the race of the victims and media coverage. Eventually, some extremists began planning terror attacks with these “scores” in mind – live streaming them while they were underway.

All this underlines how far these attacks are from being “isolated incidents .” A 2019 Anti-Defamation League report found that the deadly attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue for which Bowers will soon stand trial – itself inspired by previous mass shootings – was followed by a wave of anti-Semitic violence in the United States that resulted in at least 12 White supremacists being arrested on suspicion of engaging in terrorist plots, attacks or threats against the Jewish community. The report noted that “many of the offenders were inspired by previous white supremacist attacks.” It added that “many of the arrested individuals cite – and apparently seek to mimic – previous anti-Semitic murderers.”

But the fact that these incidents appear isolated is no accident: It is a deliberate strategy of the right, developed over the last four decades, to foil law enforcement, protect leadership from conspiracy charges for crimes committed by followers and make the movement harder to track. The idea of sparking change through terrorism is often traced to the late ’70s, to the late leader of the neo-Nazi National Alliance, William Pierce. His book, “The Turner Diaries,” a fictitious account of the exploits of a band of White supremacist revolutionaries, was intended to be a blueprint for people identifying as White warriors.

In the early days, right-wing groups openly banded together to create a movement. One of the earliest of these was the Northwest neo-Nazi gang The Order, which assassinated Jewish radio show host Alan Berg and undertook a robbery spree of banks and armored cars that netted them roughly $4 million.

But the fallout from those crimes drove these extremist groups to decentralize, according to J.M. Berger, an associate fellow with the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. After the FBI broke up The Order and the group’s leader, Robert Mathews, died in the ensuing standoff, federal authorities went after all of these organizations, charging more than a dozen White supremacists altogether with seditious conspiracy and other charges. While an all-White jury acquitted all of them, it became clear to White supremacist leaders that they were vulnerable to law enforcement as long as they maintained organizational ties with the people carrying out the “revolution” they all advocated.

This was explicitly laid out by one of these leaders, a man named Louis Beam, who was a top lieutenant in the Aryan Nations organization in northern Idaho. Writing in his magazine The Seditionist, in an essay titled, “Leaderless Resistance,” he advocated the formation of independent cells of militias that could spring into action when needed. And he encouraged “lone wolf” attacks by violent believers – attacks that would undermine public confidence in the ability of a democratic society to keep them safe and secure.

The lone-wolf strategy made a significant mark in the 1990s with a handful of horrifying terrorist attacks, such as the bombings of the Oklahoma City federal building and the Summer Olympics in Atlanta. As Berger has documented, it then took on a new life with the rise of the internet and social media in the first decade of the 21st century. A team of researchers from University College London and other institutions found that, despite the appearance of acting independently, these perpetrators were in fact highly connected ideologically and were linked to one another both online and in real life. As FiveThirtyEight wrote of the findings:

“It’s easy to look at the stats and describe these people as loners – 40 percent were unemployed at the time of their attack; 50 percent were single and had never married; 54 percent were described as angry by family members and people who knew them in real life. But the analysis also showed that these same people were often involved in ideological communities – communities built online and offline, where future terrorists sought (and often found) support and validation for their ideas. Thirty-four percent had recently joined a movement or organization centered around their extremist ideologies. Forty-eight percent were interacting in-person with extremist activists and 35 percent were doing the same online. In 68 percent of the cases, there’s evidence the ‘lone wolf’ was consuming literature and propaganda produced by other people that helped to shore up their beliefs.”

Scott Stewart, a former vice president of the geopolitical analysis firm Stratfor, explains that White supremacists and jihadists were early adopters of the internet, citing the White supremacist website Stormfront and the jihadist website Azzam.com as early examples. In those early days, White supremacist websites were cautious about calls for violence in order to avoid being suspended. More recently, however, they’ve moved to less-patrolled platforms like Gab and Discord – sites linked to several recent high-profile plots and attacks, including one by a neo-Nazi terrorist organization called Atomwaffen Division and another by the neo-Nazi group Vanguard America. Vanguard had primarily existed online prior to Aug. 12, 2017, when the group showed up in force in Charlottesville. The man who drove his car into that crowd of protesters, killing Heather Heyer and injuring dozens of others, was photographed that day with members of the group, though Vanguard has denied that he was a member.

“Unlike older White supremacist websites,” Stewart says, “these websites are totally unfiltered.”

FBI Director Christopher Wray, second from right, testifies during a Senate Homeland Security hearing in 2017.Image: Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Only in the past year or so has FBI Director Christopher Wray indicated that the agency views the new White supremacist extremism, with its less formal modes of organization, as among the most substantial domestic terror threats. “For us,” he said, “we assess that the greatest threat to the homeland is certain things that cross between both the jihadist inspired and the racially motivated violent extremist side, which is you have lone actors, typically, who are largely radicalized online and choose – sometimes very quickly go from despicable rhetoric to violence.”

But for law enforcement, attempting to prevent this kind of terrorist violence has become far more complex. The shockingly lethal attack in Las Vegas three years ago illustrates both the challenges to law enforcement – and law enforcement’s failures.

Stephen Paddock’s attack on an outdoor concert in Las Vegas in 2017 was never officially deemed a terrorist attack, though in his 10-minute slaughter before he shot himself, Paddock killed 58 people and injured 869. It was the worst mass shooting in modern American history. Understanding the evidence that his attack was ideologically motivated terrorism – and why officials never recognized it as such – goes a long way to explaining the limitations of law enforcement’s approach and the limitations in the way domestic terrorism is defined.

The massacre was a mystery: Paddock had left behind no manifesto, no explanation for the mass death.

The void of connections between Paddock and any radical movement confounded the agencies investigating the attack – the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department and the FBI. In August 2018, Las Vegas police closed their investigation, issuing a 187-page report concluding that Paddock acted alone and that his motivation remained elusive. The FBI’s report, issued in January 2019, also concluded that it could not determine a motive for Paddock’s attack. “I don’t think they did that thorough of an investigation,” survivor Christine Caria said of the FBI’s three-page report. “It seems like it was really fast.”

The police report was emphatic that, despite receiving 2,000 investigative leads, 22,000 hours of video and 252,000 images, “nothing was found to indicate motive on the part of Paddock or that he acted with anyone else.” It asserted that “there was no evidence of radicalization or ideology to support any theory that Paddock supported or followed any hate group or any domestic or foreign terrorist organization.”

To Daryl Johnson, a former Department of Homeland Security domestic terrorism analyst who served as a consultant to this project, those results signify a problem with how law enforcement sees domestic terrorism. He’s combed through the reports and believes their inconclusive outcomes were the result of antiquated frameworks that have little to do with the realities of modern domestic terrorists – such as the insistence on organizational affiliation.

“It’s important to note that most right-wing domestic terrorists today do not belong to terrorist organizations with defined membership,” Johnson has written. “So when authorities state Paddock acted alone or had no known group membership, it’s entirely possible that he still had a social or political motivation, as well as embraced extremist beliefs.”

Like many of his lone-wolf predecessors, Paddock didn’t have a lot of friends. Many of those who knew him, though, agreed that he had a thing about guns and the Second Amendment and harbored a deep fear that the government would attempt to take them away.

Although Paddock left no manifesto and acted alone, Johnson could easily trace the connection to a distinct ideological strain – the 1990s conspiracy theories about a nefarious New World Order plot by a cabal of mostly Jewish elites to enslave mankind.

Johnson points to Paddock’s intense involvement with gun ownership. According to the Las Vegas police investigators, Paddock had begun collecting guns and became increasingly paranoid about them. In a single year starting in October 2016, he purchased at least 55 weapons, most of them rifles, to complement what was already an arsenal of 29 guns.

One acquaintance recalled him defending the Second Amendment “with an incredible degree of vigor.”

Another thread was his extreme disdain for the federal government. Paddock’s brother later told investigators that part of Paddock’s motivation for taking a job with the Internal Revenue Service was his desire to avoid paying taxes, which he loathed deeply: He worked for the IRS in order to learn how to hide his income, his brother said.

Multiple people, including a real estate broker with whom Paddock had dealings, described how he hated the government and hated paying taxes, even moving property ownership from California to Texas and Nevada in order to avoid them. Those beliefs were a bedrock for a radical anti-tax movement that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, when Paddock was at the IRS.

Others who had dealings with Paddock described his affinity for right-wing conspiracy theories about the U.S. government. As the Daily Mail reported, a sex worker he had taken up with said that Paddock would “often rant about conspiracy theories, including how 9/11 was orchestrated by the U.S. government.” Another witness told police that she heard Paddock, just days before the shooting, ranting about 1990s armed Patriot movement standoffs with federal officers.

Looking at all the evidence, Johnson believes mental illness played a role, but violent anti-government extremism was the catalyst. He said it was plausible that Paddock may have been following a right-wing playbook, aiming to provoke an overzealous government response like a crackdown on gun ownership, “thus igniting a violent counter-response by the civilian population.”

“The Paddock case is odd in that if there were the same number of links to ISIS or Al Qaeda ideologies, there would be no question that the government would highlight them and call him an Islamist terrorist,” said Michael German of the Brennan Center, another expert on domestic terrorism consulted for this study, by email. “But here, law enforcement tried to hide and downplay his many links to far right groups/ideology. If you are going to characterize someone like Muhammad Abdulazeez” – the alleged radical Islamist responsible for the lethal attack on Chattanooga, Tennessee, military installations in 2015 – “as an Islamist terrorist, then I think you have to call Paddock a far-right terrorist.”

A series of arrests in domestic terrorism cases by FBI agents in 2020 indicate that the agency is putting some weight behind Wray’s insistence that the agency now views “racially motivated violent extremists” as the nation’s most significant domestic threat. The arrests included members of the neo-Nazi terrorism organization The Base, charged with planning acts in Virginia and Georgia in January, as well as nationwide arrests of members of the fascist band Atomwaffen Division, for planning and committing local acts of domestic terrorism against journalists, in February.

These were each preemptive arrests, and each involved aggressive monitoring of the behavior of right-wing extremists in corners of the internet where they believed they were secure. They serve as indicators that the agency may finally be catching up to the nature of the threat it is charged with preventing. Another came in May 2019, when Michael McGarrity, then the FBI’s counterterror chief, told Congress that of the bureau’s hundreds of open investigations into “racially motivated violent extremism,” “a significant majority are racially motivated extremists who support the superiority of the White race.”

However, there are also clear indicators that the FBI’s efforts in improving in these areas remain hampered by its conservative culture and outdated views about the nature of domestic terrorism. The FBI acknowledged to Reveal that “Individuals affiliated with racially motivated violent extremism are responsible for the most lethal and violent activity and are responsible for the majority of lethal attacks and fatalities perpetrated by domestic terrorists since 2000.” And yet the bureau said more than 80% of its 5,000 open counterterror investigations still relate not to homegrown extremists, but to the “international” threat – a category that sweeps up Islamist domestic terror threats as well, thanks to tenuous ties or even expressions of allegiance to foreign jihadis. Arrests, too, emphasize the Islamist threat, with 121 Islamist arrests in 2019, according to the FBI, versus 107 related to domestic extremists.

The bureau’s insistence on using more generic language – “racially motivated violent extremists” – to describe what primarily is far-right White nationalist terrorism suggests that the FBI, especially under Wray’s leadership, has been reluctant to name the White nationalist threat. It also indicates that the agency may have not fully let go of the controversial claim that “Black Identity Extremists” pose a significant terrorist threat. That emphasis, exposed in 2017, triggered harsh criticism from Senate Democrats.

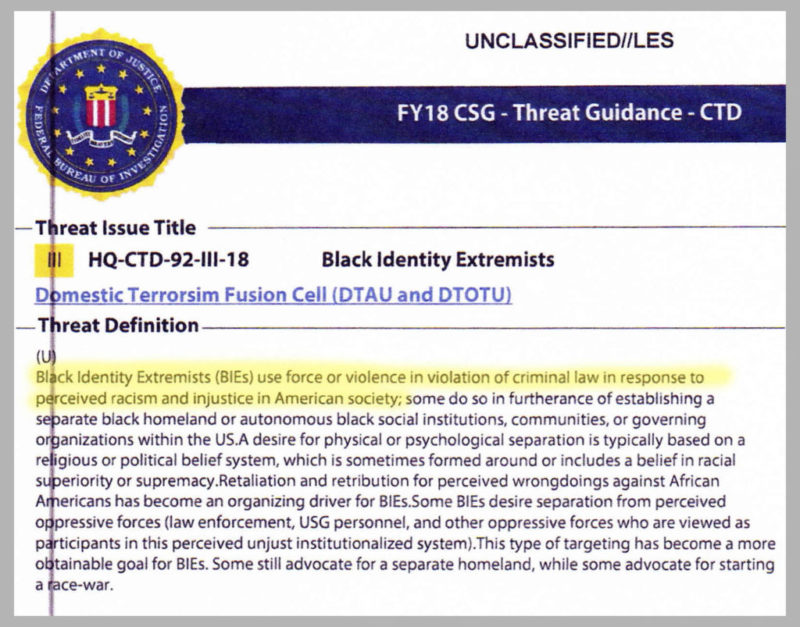

Another set of FBI counterterror documents uncovered in August 2019 by journalist Ken Klippenstein illustrates that even though the bureau has dropped formal use of the category “Black Identity Extremists,” its counterterrorism strategy still designates a similar category as a threat. As the documents – titled, “Consolidated Strategy Guide,” and covering fiscal years 2018-2020 – showed, the FBI folded the pressing White nationalist terror threat into an umbrella term, “Racially Motivated Violent Extremists.” It then divided that threat into two categories: Black and White.

In its 2018 strategy guide, the FBI still listed “Black Identity Extremists” as a “priority domestic terrorism target” along with White supremacist extremists.

Excerpt of an FBI counterterrorism strategy guide leaked to journalist Ken Klippenstein at TYT. Though the FBI came under fire when its use of the term “Black Identity Extremists” was made public in August 2017, the term still appears in its 2018 guidance.

The following year the two designations were combined into a category called “Racially Motivated Extremism.” By then, “White Racially Motivated Extremists” were rated a “medium” threat, while the document says the threat from “BRME (Black Racially Motivated Extremist) lone offenders and small cells is likely to remain elevated.”

As Klippenstein reported, the documents indicate that the FBI effectively viewed the Black Lives Matter movement as a terrorist threat. “The FBI judges BIE (Black Identity Extremist) perceptions of police brutality against African Americans have likely motivated acts of premeditated, retaliatory lethal violence against law enforcement,” one document reads. “The FBI first observed this activity following the August 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the subsequent acquittal of police officers involved in that incident.” The documents also exposed the FBI’s plans to counter this perceived threat, including the use of undercover employees and confidential informants through a program the agency dubbed “Iron Fist.”

Our exhaustive 12-year catalogue of domestic terror plots and attacks show just how far off the mark the FBI’s framework is. Violence from Black extremists has been, on rare occasions, a potent threat, as one incident from late 2019 illustrates – David Anderson and Francine Graham’s Dec. 10 attack on a cemetery and a kosher deli in Jersey City, New Jersey, in which four people were killed and three injured. Yet this attack is among only a handful in our 12-year database that could even arguably be classified as a form of Black nationalist terrorism. Those incidents are completely overshadowed by the 164 involving far-right extremists – including 52 incidents involving White supremacist ideologies.

“There are many in law enforcement who do take these domestic, right-wing and White nationalist threats seriously,” said J.M. Berger, the terrorism expert. “But it’s a complicated field of study. The organizations are small and fragmented, and they cooperate across ideological lines in complicated ways. It’s really hard to understand the landscape, and it requires investment to build expertise, and support from policy makers and politicians. It’s not clear whether that can happen in the current political environment.”

Stan Alcorn, Darren Ankrom and Soo Oh contributed to this story. It was edited by Sarah Blustain, Esther Kaplan and Matt Thompson, copy edited by Nikki Frick and Stephanie Rice and fact-checked by Maha Ahmed, Hannah Beckler, Nikki Frick, Richard Salame and Nina Zweig.