“I didn’t think he would call the police,” Clark said of his friend’s boyfriend. “But I do know she’s a woman. Ain’t no man got no business beating a woman like that.”

More than three months later, Clark remains in jail, locked in close quarters as a pandemic rages. For 23 hours a day, Clark said, he is confined to a large dormitory-style barracks alongside dozens of men, unable to maintain any kind of social distancing. The Pulaski County Regional Detention Center, which is holding Clark, reports that there are not currently any confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the facility, and that all employees and detainees are given face masks. But with the virus spreading rapidly through prisons—some 57,000 incarcerated people had tested positive as of July 7, and at least 651 prisoners have died, according to The Marshall Project—Clark, who is 62, worries about his safety. He doesn’t think he should have been jailed for his offense, given the risk of catching the virus.

“I’m a nonviolent offender,” he said. “People that work here, they interact with the outside. They can transport Covid to me, and I’ll never get to see my kids again.”

That a minor incident could have outsize consequences on Clark’s life is a story that is sadly familiar to him. Four years earlier, Clark was arrested on a drug possession charge and sent to prison just as a child welfare case was unfolding against him and his then-girlfriend, Nicole. While a journey through either of these two broken systems—the criminal justice system or the child welfare system—would have been fraught, the combination ensnared Clark in an impossible predicament. Struggling to navigate the two bureaucracies, as well as an unforgiving Clinton-era child welfare law, Clark lost three of his children—for good; his parental rights were terminated. It was a loss so profound it unraveled Clark, setting him on the path that led to his rearrest in early May.

Clark’s saga began in 2016, a decade after he and his immediate family moved from New Orleans to Arkansas to escape the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. At the time, he was living with Nicole and their two children in a two-bedroom apartment near a park in Fort Smith. Clark relished the small moments of fatherhood: reading Charlotte’s Web to his daughter Kabrina before bed, or making his son Kendrick’s peanut butter and jelly sandwich the way he liked it, with a smidgen of maple syrup in between the two gooey layers. When B.J. would allow it, Clark also spent time with his daughters from that relationship. Clark, who had spent years of his own childhood in foster care, wanted to be present for his children in ways his biological parents had not been for him. And for a while he was.

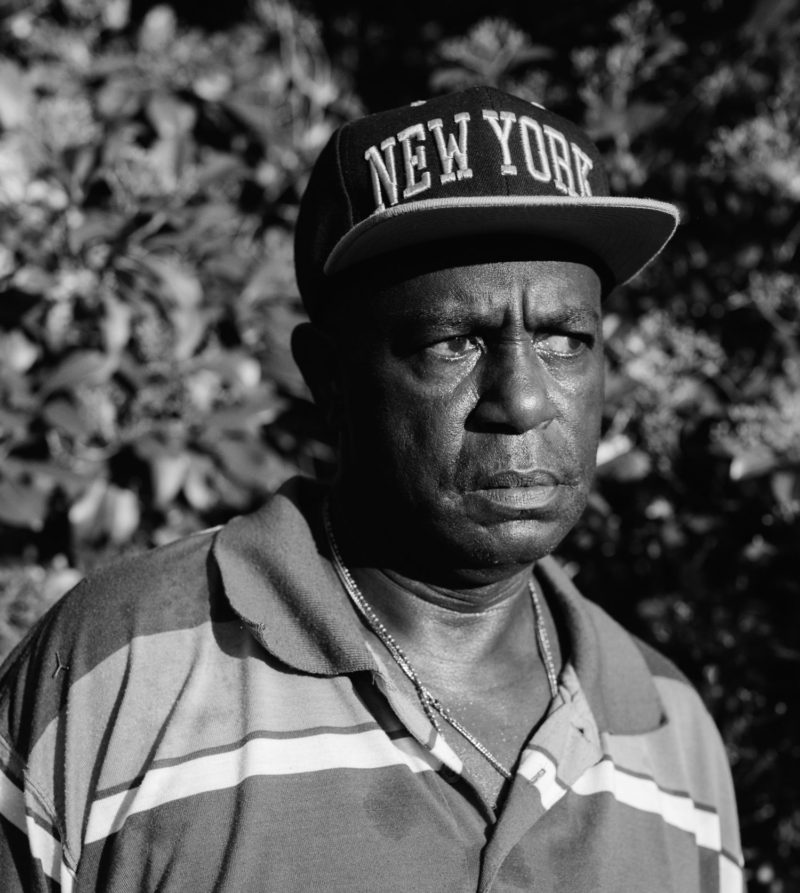

Image: Rana Young / Type Investigations

Then, in March of that year, when Nicole gave birth to their third child, Kendall, she tested positive for marijuana. The newborn did not have traces of it in his system, but under Arkansas’s Garrett’s Law, enacted in 2005, the fact that he had been exposed to drugs meant that doctors had to report Nicole to the state police or the Division of Children and Family Services (DCFS). The DCFS began an investigation into the family and ultimately opened a protective services case, in which the agency monitored the family for signs of child maltreatment and gave the parents a case plan to follow. Nicole and Clark, who had also admitted to smoking marijuana, were ordered to attend a Department of Human Services (DHS) meeting, remain drug- and alcohol-free, and allow DHS case workers into their home for drug and alcohol screenings.

During their first visit to the DHS, Clark and Nicole played with their children while a social worker observed. They also submitted to drug tests and passed, Clark said. As long as the investigation remained open, both parents had to submit to random screenings. “We gotta do this together,” he told Nicole. They made a pact to abstain from drug use, and for a while they were successful. “I was negative, she was negative,” Clark said.

Then, a month later, in April 2016, a caseworker dropped into the family’s home for a follow-up visit. According to the subsequent DHS report, Nicole tested positive for methamphetamine, amphetamines, and marijuana. Clark, who said he hadn’t so much as smoked marijuana since the case file was opened, wasn’t home during the visit and wasn’t tested. Yet the DHS removed their three children on grounds of “neglect” and “environmental issues,” citing the mother’s drug use and the poor, unsanitary condition of the home, including “electrical outlets without covers, bed bugs in the corner of the ceiling, pull-out sofas…on the floor,” according to the DHS report. A neighbor called Clark to tell him his children were being removed, and he arrived, drenched in sweat and out of breath, just as Kendall, Kabrina, and Kendrick were being loaded into a van.

“What’s wrong?” he recalls asking the DHS representative. “I made it here. I ran all the way from 11th Street. I got here as fast as I could.” But the DHS case worker said he was too late and proceeded to take the kids away. She only allowed Clark to say goodbye.

Image: Rana Young / Type Investigations

Since that day, Clark’s three children with Nicole have been somewhere in the foster care system; he does not know where. He has not seen them. But he pines for them. In his back pocket, he carries two photos of Kendall, the only tangible remnants of his youngest child; in his memory, he carries the early mornings he spent on the sofa watching TV with Kendrick, who was 5 the last time they saw each other, or the afternoon dance-offs with his daughter Kabrina, who was 4.

“I want my kids back, I don’t really care about nothing else,” Clark said, during one of our many conversations about his fight to win back his children.

“If I get my kids back it will feel like a thousand pounds of pressure been relieved off me,” he added. “Really, because in my mind, that’s all I live for.”

When the DHS removed Clark’s children—Kendall, Kabrina, and Kendrick—they joined the ranks of the nearly 443,000 kids in the United States foster care system. In many cases, eager parents are on the other end, working hard to get their children back, and for years, Clark was one of those eager parents. But his battle was more complicated than most because it was waged at the crossroads of the child welfare and criminal justice systems, which have disparate missions and rarely communicate well with each other.

In the spring of 2016, shortly after his kids were removed from his home, Clark served a little more than a year behind bars for drug possession. “I was damaged,” Clark says of that time. “I was at my lowest point.” Instead of pressing his attorney to fight the charges, he opted to go to prison on the theory that serving the time could be an opportunity to get his life in order, so he could be present for his children when they came home. “I’m going to take my lick,” he told himself; then he would “come on back and be that standup guy I’m supposed to be.”

But far from an opportunity to prepare for his kids’ return, prison turned out to be the wedge that drove him further away from them. The problem wasn’t just that Clark missed his children desperately, that he worried about how scared they must be; it was that, while in prison, Clark’s child custody case moved forward—without him.

What made this situation particularly challenging is that Clark’s custody case was up against an unforgiving time line. This time line was set some two decades earlier, in 1997, when President Bill Clinton signed the Adoption and Safe Families Act, or ASFA. The law requires state foster care agencies to begin terminating parental rights whenever a child has lived in foster care for 15 of the last 22 months, with very limited exceptions. Since then, some states have decided to do it even faster. In Arkansas, where the child welfare system has been mired in problems, the time line is only 12 months. Lawmakers say they passed the ASFA to offer permanence to children perennially bouncing between foster care placements and group homes, but it has also made it extremely difficult for incarcerated parents to maintain rights to their own children.

Mass incarceration affects millions of families in every state across the country, yet families in some states fare worse than others. Arkansas has the fastest-growing prison population in the country, a trend that has had a tremendous impact on families there. More than 100,000 children in Arkansas have experienced parental incarceration, or nearly one in six kids, making Arkansas the state with the highest proportion of children affected by this country’s system of mass imprisonment.

Incarcerated parents across the country face a higher likelihood of losing their parental rights than parents in child welfare cases accused of serious abuse. In 2018, The Marshall Project analyzed nearly 3 million DHS child welfare cases, finding that in one out of eight, incarcerated parents lost their parental rights, regardless of the seriousness of their crime. According to the data, at least 32,000 incarcerated parents had their children permanently removed between 2006 and 2016 without being accused of physical or sexual abuse; instead, many separations were tied, in part, to poverty. Nearly 5,000 of those cases involved parents who appear to have had their parental rights severed as a result of their imprisonment alone.

Child welfare policy has often been polarizing, with theories as to the best method to protect children swinging wildly over the last 50 years from solutions privileging removing kids from the home to those prioritizing family preservation—and back again.

In the early 1990s, the pendulum was swinging hard in the direction of family separation. For a decade or so prior, the emphasis had been on family reunification, with child protective services required to make “reasonable efforts” to avoid unnecessary removal of children from their families. But critics believed this approach led social workers to try too hard to keep children in their homes, even in dangerous situations. Protecting children and giving them permanence—not necessarily with their birth family—became the dominant national narrative.

The campaign to pass the ASFA emerged out of this anxious moment. It was spearheaded by Hillary Clinton, then the first lady, and Republican Senator John Chafee of Rhode Island, with strong bipartisan support. The ASFA amended the Child Welfare Act by limiting “reasonable efforts” and speeding up the adoption process to make it easier to remove children from abusive households. Its supporters harbored some harsh ideas about the kinds of families who wind up in the child welfare system.

“We will not continue the current system of always putting the needs and rights of the biological parents first,” Chafee said before the Senate. “It’s time we recognize that some families simply cannot and should not be kept together.”

Senator Mike DeWine, now the Republican governor of Ohio, who authored language narrowing the scope of “reasonable efforts” in the bill, directly attacked the idea of seeking to keep natal families together. “Too often, reasonable efforts…have come to mean unreasonable efforts,” he said on the Senate floor. “It has come to mean efforts to reunite families which are families in name only. I am speaking now of dangerous, abusive adults who represent a threat to the health and safety and even the lives of these children.”

The bill passed almost unanimously, with Hillary Clinton presiding over the signing ceremony.

Now, some two decades later, opinion about the success of the ASFA remains divided. Among its supporters, the ASFA is hailed as a landmark child welfare effort. “ASFA established for the first time within federal policy the principle that maltreated children must be ‘the paramount concern’ of the child protection system,” Cassie Statuto Bevan, professor of social policy and practice at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote in an article. Statuto was a staffer on the Ways and Means Committee that oversaw passage of the ASFA. She believes it remains a “highly successful law” that has produced “a significant decline in the average time between removal of a child from his/her home and termination of parental rights.”

Yet this newfound speed can also pose a problem. Throughout the country, thousands of parents have lost their parental rights as a result of the ASFA’s time line. Child welfare advocates say the ASFA, in practice, encourages states to remove children without sufficient cause from their families, especially poor families in which allegations of poverty-related neglect—not abuse—are paramount.

“The biggest problem in the system is the confusion of poverty with neglect and the racial bias,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. “The premise of ASFA was, ‘Oh, this vast family preservation conspiracy is forcing children to languish in foster care,’ and that’s nonsense,” he said. “It was the lack of family preservation that forced, and forces, children to languish in foster care.” Federal data shows that parental rights terminations consistently outrun adoptions.

This is the world in which Kenneth Clark found himself when his kids were removed from his home.

During his year in prison, Clark tried hard to stay on top of his child custody case. But he quickly ran headlong into the iron walls of both the prison and foster care systems. Once, during the early days of his sentence, the DHS transported him the half mile to family court for a June 2016 hearing, during which his kids were formally made wards of the state. But that, said Clark, was the last of the DHS’s efforts to comply with its obligations.

When asked for comment on its efforts in Clark’s case, the DHS said that it is not allowed to discuss individual foster care cases, but did say that its protocol is make it possible for the incarcerated parent to attend case service meetings and visitations “as they would with all parents…as allowable and available.”

In September 2016, still in jail, Clark received a DHS notice alerting him to a video conference for a hearing regarding alleged maltreatment of his infant son—specifically, regarding the agency’s allegations of neglect and unsanitary living conditions. The hearing was scheduled for October. “I showed it to the officer,” Clark recalled. “They said someone would get me. It never happened.” His failure to appear or request a continuance meant that his name was added to the Arkansas Child Maltreatment Central Registry, a DHS list of people found to be negligent or abusive of minors.

Around the same time, and without warning, Clark was transferred first to a jail in Malvern, then to a facility in Calico Rock, Ark., over 200 miles from Fort Smith. He said he stopped hearing about his children’s status and was not informed about—or transported to—any subsequent custody hearings. During that period, two other, crucial hearings took place, including a permanency planning hearing, during which the judge began the process of deciding Clark’s children’s fate. At that hearing, in March, without Clark present, the court set two conflicting plans for the children: While continuing to work towards reunification, the court set a parallel goal of moving the kids toward adoption.

Two months later, the DHS set that second goal in motion. In May 2017, Clark received notice that the agency had petitioned the court to terminate his parental rights.

At the time, Clark had just been released to a reentry program—a year before his sentence was up, because of good behavior, he said—and he was taking steps to get back on track. But with the arrival of the termination petition, his world flipped upside down. He suddenly became one of hundreds of formerly incarcerated parents across the country struggling with the challenges of reentry while fighting to preserve their parental rights. That petition, if granted, meant that Clark would permanently end the legal parent-child relationship, and his children would be eligible for adoption.

While the ASFA narrowed the scope of “reasonable efforts,” it did not do away with them altogether. According to the Federal Children’s Bureau, child welfare agencies are supposed to provide services that are “accessible, available, and culturally appropriate” in order to help families remedy the conditions that brought their children into the foster care system. Clark, according to his attorney, could reasonably expect the State of Arkansas to send notice of court hearings to the correct address, give him a case plan to complete, provide him assistance to complete the case plan, and assign an attorney to represent his interests. Yet almost none of that happened. “Reasonable efforts,” it turns out, aren’t strictly defined in federal law, giving states the power to determine what they consider reasonable on a case by case basis.

Clark did not receive a DHS case plan to help guide his reunification with his children. (He later learned that the case plan had been sent to his former home address while he was incarcerated.) But even if he had gotten one, the road to completing a case plan while behind bars would have been extremely difficult. Incarcerated parents rarely have access to the reunification services typically required by the courts, such as parenting classes, drug and alcohol abuse treatment, mental health care, or vocational counseling.

Moreover, despite petitioning for visitation while in Calico Rock prison, Clark says he never received a reply. His next attempts, while in a state-mandated reentry program called Quapaw Hidden Creek, were hobbled by a tangle of rules. The six-month program—which is considered to be incarceration, albeit more flexible—was meant to offer people returning from prison a combination of structure and support, a safe place to live, and a chance to focus on their sobriety while also trying to secure a job. Clark had hoped to use this time to sit down with a social worker from the DHS and make a plan for reunification. But without an appointment, the agency didn’t need to make efforts to get him there, and the initial restrictions of the reentry program barred him from leaving the grounds except to go to work and scheduled court appearances.

The DHS did not take these restrictions into account, so the ASFA clock continued to tick. The May 2017 petition to terminate his parental rights noted that Clark’s children had been in foster care for 12 months, reaching Arkansas’s deadline, and the parents hadn’t made significant progress to rectify the problems that had resulted in the children’s removal. Clark was found to have failed to provide reasonable support and maintain regular contact with his children, effectively abandoning them. The petition further argued that Clark had not complied with his DHS case plan—which, of course, he had never received. (The petition also noted that Nicole, the mother of his three kids, had failed to successfully meet her case plane. Clark and Nicole had broken up early in his prison sentence. She moved, her phone was disconnected, and they had not been in touch.)

The petition arrived like a meteor from outer space. Desperate not to lose his kids, Clark says he tried reaching the DHS before the court hearing, in June. Those calls, he says, were never returned. A staffer at Quapaw eventually led him to Dee Ann Newell, founder of Arkansas Voices for the Children Left Behind. Newell, who had witnessed countless terminations of parental rights and knew the system well, took Clark on as a client. “Fathers are the least important in the whole system,” Newell said. “It’s a huge statement on our system and society on whether a father is worthwhile.”

Newell encouraged Clark to work around his restrictions—specifically, the requirement that he not leave Quapaw Hidden Creek—by writing a letter to the DHS. The agency had left Clark, a parent eagerly trying to reunite with his children, relegated to pleading his case on a piece of paper. He asked the DHS to “show mercy.” He explained that “during my incarceration, my hands have been tied somewhat,” but that while in prison he had completed parenting classes, a domestic violence program, a six-week behavior class, and other wellness courses. Now, he wrote, he planned to continue his sobriety, secure a job, and seek opportunities to prove himself as “a father and a productive member of society.” He pleaded for reunification with his children. “I love my children greatly and am in the process of making serious life changes so that I may provide a stable, drug free Christian environment for my children.”

After mailing his letter, Clark continued to follow the exacting steps of his reentry plan. He was required to wear an ankle monitor and submit to biweekly drug screenings, and he wasn’t allowed to have a cell phone. Still, he moved forward. He started a job at De Wafelbakkers, a frozen pancake purveyor, in June, trekking 14 miles to work the night shift in the sanitation department. During the day, he attended substance abuse meetings and GED classes; during the weekend, he went to church. At night, he worked, his earnings automatically placed into a savings account. He paid $98 a week in rent to Quapaw and withdrew $30 every two weeks for living expenses. The rest he saved to prepare for his release.

On June 28, 2017, Clark was scheduled for the hearing that would determine whether he would lose his parental rights. Clark had not been assigned any legal representation for an entire year, even though he had a right to an attorney at each stage of the proceedings. So when he arrived in court for his hearing he asked for a public defender, which he was granted. The court rescheduled Clark’s hearing, ordering him to return in 16 days—a notably short amount of time to prepare for getting his children back. At the same time, the court terminated Nicole’s parental rights.

When Clark returned to court, it was evident that the brief time his lawyer, DeeAnna Weimar, had been granted to prepare would shape his hearing. She had failed to get various essential documents like pay stubs, proof of clean drug screenings, certificates of completion of various classes, letters of support, and a list of restrictions imposed by his reentry program that had prevented him from completing portions of his case plan—anything that would have bolstered his chances of reunification. Nonetheless, Weimar pulled together what evidence she did have to argue that Clark should be reunited with his children. (Through an assistant, Weimar declined to comment for this article.)

At the heart of Weimar’s argument was the claim that the DHS had failed to do its part to make “reasonable efforts” to reunite Clark with his children, as required by federal law. Clark could reasonably expect the State of Arkansas to send notice of court hearings to the correct address; to give Clark a case plan to complete; to provide him assistance to complete the case plan; and to assign him an attorney—but almost none of that happened. Weimar asked the court not to terminate his rights and instead offer the services that should have been offered before.

The DHS representatives who were on hand for the trial appeared unmoved by these arguments. They countered that Clark had abandoned his children and called for his parental rights to be terminated. A DHS caseworker, Chelsea West, testified that she had offered Clark services—but then admitted that she had never contacted him while he was in prison, or at Quapaw, to offer services. She also claimed she hadn’t known where Clark was, though the DHS had obtained the sentencing order; the agency thus knew exactly where he had been sent.

As for the DHS lawyer, Katharine Hughes, she largely doubled down on these arguments; she ignored the DHS’s responsibility to put forth reasonable efforts to reunite the family and instead insisted that Clark should have found a way to get in touch with his children, that his incarceration constituted abandonment.

“Whose fault is it that you were incarcerated for that time?” Hughes asked.

Clark took responsibility, saying, “It was mine.”

Image: Rana Young/Type Investigations

Then Clark tried his best to make his case. “I think it would be in the best interest of my children to live with me,” Clark pleaded. “I’m ashamed and I’m embarrassed for what I took my kids through. And the man I am today, I’m not that man that I was a year ago.” He noted that the department had consistently clean drug tests for him that they failed to introduce and stressed that he had persisted in seeking custody despite DHS’s failure to offer him help.

The question of time, the issue at the core of the ASFA, hovered over the proceedings. “How long do your children need to wait before they get to have permanency?” Hughes asked Clark. He explained that he would be released from Quapaw in two months, and that by then he would have things in order for his children. But Hughes remained unmoved. “So, the kids should at least wait until September, and then however long it should take you to get everything set up, get your house set up, get everything ready for the kids?” By this point Clark and his children had been separated for close to 15 months, and it didn’t strike Clark that two more months was unreasonable given the DHS’s admission that it had failed to hold up its side of the plan.

Aubrey Barr, the court-appointed attorney who represented his children, shifted to a line of questioning about his financial status that child welfare advocates describe as common. She wanted to know how much he earned on his job, and he answered $10.25 an hour, at the time nearly $2 an hour above the state minimum wage. Barr recommended that Clark’s rights be terminated, and then, as a final twist of the knife, asked the judge not to allow a final visit.

That judge, Annie Powell Hendricks, applauded Clark for his strides—and then told him that his children deserved permanency and it was in their best interest to terminate his parental rights. “I think your children are adoptable. They’re young and happy children with no physical or medical conditions, who are in pre-adoptive homes,” she said. (The judge was wrong. At the time, Clark’s son Kendrick, then 6, had been reported by the DHS to have behavioral problems and was in therapeutic foster care; a boy in his situation—a Black child, who isn’t an infant, with reported behavioral issues—will almost certainly have more trouble finding a permanent home.)

Hendricks argued that the issues that put the kids in state care hadn’t been remedied. She argued that there was no proof Clark could provide appropriate housing for the kids; no proof that he had completed drug and alcohol treatment in prison or had mitigated the risk of harm from an unrelated domestic violence complaint back in 2014. It was as if Clark’s testimony and paperwork for the prison drug treatment program, the domestic violence program, and the job at De Wafelbakkers didn’t exist. That Clark was due to be released from the reentry program soon and was well positioned to have housing and transportation in place did not appear to carry any weight at all. The ASFA alarm had rung.

“The Court is going to find abandonment, because it has been fifteen months,” the judge ruled. She briskly denied Clark a final visit.

During the hearing, Clark’s lawyer had tried to argue that Arkansas’s Act 993, a new law that clarified the role of child welfare for children of incarcerated parents, articulated the “reasonable efforts” language in a way that exposed the DHS as negligent in Clark’s case. The law says: “The Department of Human Services shall: Involve an incarcerated parent in case planning; Monitor compliance with services offered by the Department of Correction to the extent permitted by federal law; Offer visitation in accordance with the policies of the Department of Correction if visitation is appropriate and in the best interest of the child.” The law was passed on April 7, 2017, three months earlier. Unfortunately for Clark, it had yet to go into effect.