Data analysis by Sinduja Rangarajan and Taylor Eldridge.

Carolina Ciru told herself it was going to be okay when she saw the flashing blue lights in her rearview mirror on a Friday afternoon in February. Ciru, a 42-year-old Honduran immigrant, had been stopped before while driving near her home in Lawrenceville, Georgia. The last time, she’d told the officer she didn’t have a driver’s license, and he wrote a ticket and told her to find someone to drive her home. But this time was different. Ciru was arrested for driving without a license, a misdemeanor. She was handcuffed, put in the back of a police cruiser, and delivered to the Gwinnett County Jail in Lawrenceville. Her 22-year-old daughter, Valerie, tried to pay bail but was told her mother would not be allowed to leave.

Three days later, Ciru was driven three hours south to the Irwin County Detention Center, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility. In May, she told me over a video call that she was certain ICE would release her. “They have to let me out of here,” she said. “I think they will.” Ciru, who has diabetes and a pacemaker for a heart condition, had arrived at Irwin just as the pandemic was approaching; by the time we talked in May, the coronavirus was spreading inside the facility. Her health conditions put her at clear risk. “I should not be here during this,” she said. “I should not be here at all.”

Ciru lived with her partner and her five children about 30 miles east of Atlanta. She had been in the United States for 25 years, most of them in Gwinnett County. “Gwinnett is my home,” Ciru said. “It is where everything in my life is.” Her 13-year-old twins and teenage son were at home with her partner, as was her 20-year-old son, who is autistic and prone to seizures. “Nobody else can keep him safe,” she said. “I am the one who cares for him.”

Inside Irwin, Ciru had befriended a group of women from Gwinnett County who had also been detained by ICE after being arrested by local police. Monica, who was born in Uruguay, had been picked up on a domestic assault charge, even though she said she was defending herself from her abusive husband. Camila, a Dominican woman, had been charged with credit card fraud and turned over to ICE as she awaited trial. (I have changed their names at their request.)

The Gwinnett County Jail.Image: Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images

All of them were in immigration detention not because federal agents had staked out their homes or caught them in a workplace raid, but because Gwinnett County Sheriff Butch Conway had sent them there. For more than a decade, Conway has deployed his deputies as de facto immigration agents and turned his jail into a depot for undocumented immigrants headed for deportation. In the last decade, Conway’s agency has identified more than 21,000 people to hand over to ICE. Since 2017, Gwinnett, Georgia’s second-most populous county, has helped to detain more immigrants than any other county except five counties in states along the US-Mexico border.

“Honestly,” Ciru said, “my issue isn’t with ICE, not my first issue. My issue first is with the cops up there. The police up there they treat us like we’re nothing.” Camila told me, “Up in Gwinnett, they hunt for immigrants.”

About 267,000 noncitizens were deported by ICE last year. That number was driven in large part by local sheriffs like Conway; 70 percent of ICE arrests originate in the criminal justice system, mostly in jails. And as President Trump’s war on immigrants has expanded, sheriffs have become some of its most enthusiastic foot soldiers. In Gwinnett and more than 140 other counties, ICE has authorized and trained sheriff’s deputies to assist it. In most of these counties, local officers use federal databases to check the immigration status of people booked into local jails and then place warrantless immigration holds on noncitizens who may be deportable. Since 2017, the number of sheriffs who have agreed to participate in this program, known as 287(g) for the section of the federal code that created it in 1996, has spiked. Most are in rural counties across the South and Southwest. In addition, hundreds of other sheriffs comply voluntarily with ICE’s requests to keep immigrants in custody for up to 48 hours until agents pick them up. Texas now requires its jails to do so, and lawmakers in several states, including Georgia, have barred counties from imposing “sanctuary” policies that curtail ICE’s access to local detainees.

While cooperation between local law enforcement and ICE has grown, so have efforts to frustrate these initiatives. Civil rights activists and advocates for immigrants say sheriffs’ collaboration with ICE encourages racial profiling, discourages immigrants from using public services, and turns any interaction between noncitizens and the police into a potential conduit to deportation. Since Trump took office, hundreds of counties and several states have passed ordinances prohibiting jails from complying with ICE requests unless presented with a warrant signed by a federal judge to detain a person. California’s 2017 “sanctuary state” law set new limits on ICE’s ability to use local jails to identify and detain noncitizens. At a 2018 meeting with California mayors and sheriffs, Trump described it as “a law that forces the release of illegal immigrant criminals, drug dealers, gang members, and violent predators into your communities.” In June, the Supreme Court declined to hear the administration’s challenge to the law.

Jails’ role in detaining immigrants has increasingly become a local political issue. Amid public pressure, more than 20 law enforcement agencies, mostly in urban counties, have ended their 287(g) programs in the past three years. In 2018, voters in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, which includes Charlotte, kicked out a sheriff who’d participated in the program. In June, the sheriff in Athens, Georgia, who had honored warrantless detainer requests even without a 287(g) agreement, lost to a primary challenger who had described the effects of local ICE collaboration on immigrant communities to the Appeal as “almost a level of terrorism when people are living in fear to the point that they will not ask for help.” Now, in several other counties, sheriffs who have stood behind 287(g) agreements or otherwise assisted ICE are facing credible challenges in November. The fight has also come to Gwinnett County.

The American sheriff holds a peculiar office. Most of the country’s more than 3,000 sheriffs are elected and often not accountable to a county executive and thus have no real oversight beyond voters who typically keep reelecting them. (As of 2014, one-third of the sheriffs who had overseen the nation’s 200 largest jails had held office for 15 years or more.) In some jurisdictions, deputies make arrests. But their main job is running local jails and they have overseen vast expansions of the pretrial detention system. They often operate jails with near impunity; reports of abuse, negligence, and unchecked violence abound. Some big-city sheriffs oversee budgets of more than $1 billion. Amid calls for systemic shifts in policing and incarceration, sheriffs are now facing long-overdue scrutiny.

Butch Conway, whom voters have elected six times over a quarter-century, has played the role of the iron-fisted good-old-boy sheriff with relish. In 2000, he created a riot control team for the county jail; according to a lawsuit filed by 83 former detainees, the unit was used to viciously punish rulebreakers. In January, a former deputy on the riot control team was indicted for allegedly punching a detained woman in the head. When a woman complained about poor medical care inside his jail, Conway posted on Facebook, “If you don’t like the way we run the Gwinnett County Jail, stay out of it.” In 2018, the Department of Justice ordered him to repay nearly $70,000 in asset forfeiture funds he’d used to buy himself a muscle car.

But Conway’s signature feat has been wholly extracurricular; detaining suspected undocumented immigrants is not part of his job description. Conway even let ICE set up its own office inside the jail to supervise and streamline its work. At a 2018 visit to the White House, Conway boasted about the tens of thousands of “illegal aliens” that had been identified inside his jail. “We’ve cooperated with our partners with immigration the 20-plus years I’ve been sheriff,” Conway told Trump. “We’ll continue working with ICE and we certainly appreciate everything that you folks are doing for us. We need the help.” Even the coronavirus hasn’t slowed Conway’s commitment to detaining immigrants. Earlier this year, ICE limited its detention operations, picking up fewer people inside the country, including from Gwinnett County Jail. Nevertheless, Conway’s deputies flagged more detainees than ICE could pick up.

Conway has said that his goal in cooperating with ICE is to ensure public safety. “The only interest I and this agency have had in immigration is when someone commits a crime,” he told reporters at a press conference in January. Two months later, he re-upped his cooperation agreement with ICE for the third time. This one had no expiration date. “I would deport citizens if I could,” he said earlier this year. “A lot of the illegal aliens that we identify and hold for ICE, they’re preying on their community.”

The data doesn’t bear that out. Forty-five percent of the 4,200 people whom Conway’s jail helped detain for ICE between January 2017 and July 2019 were arrested by local police for driving without a license, or other traffic violations such as failure to use a blinker, or running a stop sign. An additional 7 percent of the county’s ICE detentions stemmed from DUI charges, according to our analysis of county data. The remaining 48 percent were charged with, but often not convicted of, other misdemeanors and felonies; rather than going through the criminal court system, which may have meant bonding out before trial, they were moved to ICE detention.

Conway has insisted that his zeal for detaining immigrants is not racially motivated. “I’m not racist. Never have been,” he told reporters earlier this year. Yet he has made no secret of his views on race, policing, and politics. In 2015, he said anti–police violence activists were “domestic terrorists” who advocate murdering cops. The following year, he signed on as a leader of Trump’s Georgia campaign team. In July 2019, Conway invited an anti-immigrant activist named D.A. King to a panel discussion about the 287(g) program. (King, the founder of a Georgia organization that the Southern Poverty Law Center has called a hate group, was reported to have once said that undocumented immigrants are “not here to mow your lawn—they’re here to blow up your buildings and kill your children, and you, and me.”) In 2019, a reporter for the online magazine Filter found that Conway had “liked” the Facebook page for the New Confederate Army, which promotes Southern secession.

For generations, Gwinnett County has been a bastion of white conservative political power. But that is changing—just as Conway is moving on. After a quarter century as sheriff, Conway announced early this year that he would not run for reelection, citing personal reasons. He tapped his chief deputy, Lou Solis, to succeed him. (Solis’ bio notes that he served as the Georgia State Patrol’s Spanish-speaking hostage negotiator.) Neither responded to requests for an interview, but Solis recently called the 287(g) program “priceless” and argued that deporting immigrants keeps residents safe.

In 2016, Conway ran unopposed and won 97 percent of the vote. Yet the easy path to the sheriff’s office that Conway long enjoyed may no longer be open to Solis. Due to immigration from Asia and Latin America and a growing Black population, Gwinnett has gone from being 90 percent white in 1990 to 36 percent white today. Flags from more than 100 countries hang in the lobby of a local high school, one for each country its students’ families immigrated from. “We are the most diverse county in the southeast United States,” the head of the local Chamber of Commerce recently told Georgia Trend Magazine. “We are the prototype community for the future.”

Two Democrats, both Black police officers, are running against Solis. Curtis Clemons and Keybo Taylor have pledged to end the county jail’s collaboration with ICE. “I believe that the goal of the current sheriff and others is to keep out immigrants, to keep Gwinnett County homogeneously white and conservative,” Clemons told me. He also said he’d immediately disband the riot control team and try to shrink the jail’s population by limiting the use of cash bail. “There’s no evidence that the 287(g) program has done anything good, anything to affect crime, anything to keep anyone safe,” Taylor said. “It has created an atmosphere of severe distrust and made immigrants less safe.” If Gwinnett County’s demographic and electoral trends are any indication, the winner of the Democratic primary runoff in August will likely succeed Butch Conway.

Sergeant Arelis Rivera was hired, in effect, to deal with the problem that Conway created. When I met her, she was working for the police department in the city of Norcross, one of Gwinnett County’s 10 local police agencies. Shortly after Rivera joined the department in 2013, Norcross’ then–police chief called her his “secret weapon.” A big part of her job was to build trust between police and Latinos, who are nearly half of the city’s 17,000 residents.

As a police officer, Arelis Rivera tried to build trust with the Latino community.Image: Lynsey Weatherspoon for Mother Jones/Type Investigations

Norcross is a liberal place. Its voters helped Hillary Clinton win the county in 2016. Two years later, they overwhelmingly supported Stacey Abrams for governor and helped elect two Democrats as county commissioners, the first in over 30 years. In 2018, Norcross joined Welcoming America, a network of cities that have committed to being sanctuaries for all immigrants.

When I met Rivera in her office last summer, her cellphone and landline rarely stopped ringing with calls from residents asking for help—towing a broken-down car, fighting off a mean-looking dog, assisting elderly residents with overgrown shrubs that violated the city’s stuffy ordinances. Rivera, who is Puerto Rican, hails from Chicago. She has a master’s degree in education and is the president of the Atlanta chapter of the Latino Peace Officers Association. But even all of her dedication and hustle could not overcome the mistrust wrought by years of Conway’s collaboration with ICE.

Rivera invited me to join her on a Saturday morning while she volunteered to conduct a survey of residents with a group of housing advocates. While most of the teams were easily gathering responses, Rivera, who’d worn her uniform as she said she always did when out in the community, was striking out. Among the 70-some doors she tried, only six or seven opened. “They see me, they look through the window and they don’t want to open the door,” she said as she stood outside another door. She kept knocking. A Latina girl, maybe 8 years old, looked through a window onto the walkway where we stood, and quickly shut the blinds and turned off the lights. “They can’t see the difference between me and an ICE agent. It’s very hard right now. I can’t really do my job,” she said. “We have nothing to do with immigration.”

She was right. Norcross doesn’t enforce federal immigration laws. Neither do any of the county’s city police departments or the Gwinnett County Police Department, which is separate from the sheriff. Conway’s deputies don’t patrol the streets making arrests, yet because none of Gwinnett’s cities operate their own jails, their cops must send arrestees to the county jail, where they may be flagged and held for ICE. Last year, the county police department produced two videos, one in English and one in Spanish, that appeared to explicitly rebuff Conway’s practices. They explained that the department’s policy “prohibits bias-based profiling of individuals or communities based on their known or unknown citizenship status.” Yet even though police departments in Gwinnett County do not actively pursue noncitizens, they still inadvertently wind up abetting ICE.

Rivera said she and some colleagues chose not to arrest people for minor violations, such as driving without a license, which undocumented immigrants have to do, since Georgia won’t issue licenses to them. But not every officer is like Rivera, and cops can’t exercise the same discretion over arrests for more serious crimes like aggravated assaults or shootings. From 2017 to mid-2019, the county jail put ICE holds on about 350 people who were arrested in Norcross. More than half of them were arrested for minor driving violations.

The flip side of Rivera’s forbearance is that any cop in Gwinnett who wants to target immigrants has a willing partner in the sheriff. A former county police officer told me he had become increasingly worried about racial profiling by local police since Trump took office. “People feel they can do it,” he said. “There are those officers where I am sure they say, ‘I’m going to find someone,’ and then they go make a stop.” This is not a new concern about 287(g) agreements: The former executive director of the ICE Office of State and Local Coordination told a conference of police and sheriffs in 2008, “If you don’t have enough evidence to charge someone criminally but you think he’s illegal, we can make him disappear.”

But proving that a police stop was the result of profiling is nearly impossible because cops can usually produce a legal pretext to pull anyone over. In Ciru’s case, police say she was pulled over for veering into the oncoming lane, though she believed she was stopped because she is Latina. Sometimes, however, profiling is obvious. Among the Obama Justice Department’s charges against the notorious Phoenix sheriff Joe Arpaio was that he pushed the aggressive profiling of Latino drivers, who were funneled through his jail into ICE detention. Arpaio was found guilty of criminal contempt of court in 2017 after he continued to profile suspected non-citizens. A month later, Trump pardoned him. (In August, Arpaio lost his bid to run again for his old job.)

Rivera, who no longer works for the Norcross Police Department, said she did all she could to distance herself from the county sheriff: “We have nothing to do with immigration, and we try to tell people that as much as we can.” But Conway’s jail has a long reach. Camila, one of the women Ciru met in immigration detention, had been put in Gwinnett County Jail in January after she was arrested by Norcross police on suspicion of credit fraud. The officer who had investigated the tip that set in motion the events that could lead to Camila’s deportation was Arelis Rivera.

The threat of deportation because of an interaction with the cops has transformed life in Gwinnett County and the counties that surround it. On a Thursday afternoon, about 10 minutes from the police station where Rivera worked, a flock of children streamed from a bus, chattering in Spanish and English, into the front office of a housing development in Norcross and greeted Maurie Ladson, their after-school literacy teacher. The organization Ladson works for, Corners Outreach, runs four sites like this. The children’s drawings taped to the walls mostly displayed hearts and stick figures and palm trees. But some were heavier. “If I could change the world I will gif everyone papers so they can go everywhere. My family needs papers so I can talk with them,” read one. Ladson said about a third of the 23 kids in her middle school group, most of whom are citizens, had a parent or another adult they live with detained or deported by ICE in the last five years.

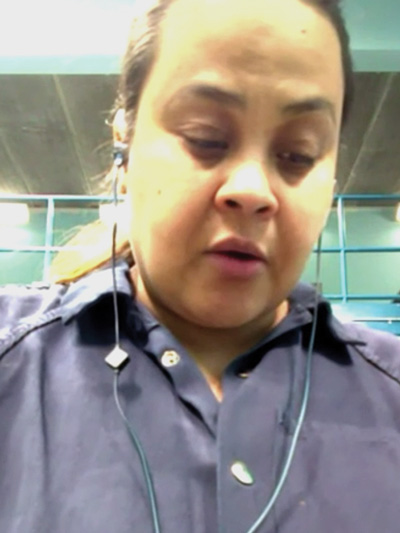

Carolina Ciru in ICE detention

“This is something that’s part of all of their lives all of the time,” she told me. “They’re completely aware of what’s happening. Most kids just know their parents will be home that evening. These kids know it’s always a possibility that won’t be true.” One mother who arrived to pick her kid up said she’d walk an hour to the grocery store, rather than risk driving. Another said she used to drive until her husband was arrested for a traffic violation and then detained by ICE. She didn’t know if he’d be deported.

When Ladson and I spoke again a few months later, more kids’ relatives had been detained. “We’re dealing with serious trauma,” she said. “It spares nobody. It sends the message, clearly, that immigrants aren’t part of this community. And it means that these kids are not safe if their parents are not.”

In the parking lot of a housing complex not far from Ladson’s program, a taxi driver named Raul was waiting for a fare. He told me that most of his clients were immigrants without licenses who fear that driving will get them deported. Almost all of his morning and afternoon fares were trips into and out of Gwinnett County. “I see it as a service to my community,” he said.

Among the many immigrants who use the services of people like Raul is Edy, a Mexican immigrant in his early 40s who lives with his wife, Gaby, and their kids in DeKalb County, just south of Gwinnett. When I met him, Edy was working in construction in Gwinnett, and he made a rule of almost always taking taxis to work. Sometimes he spent $250 a week on rides, a serious burden for his family of seven. But he knew what could happen if he was pulled over. Seven years ago Gaby’s sister was stopped, found without a license, and deported.

DeKalb County, which covers part of Atlanta, has a growing immigrant population but life there is profoundly different than it is right over the county line. In 2014, its sheriff’s department significantly limited the extent to which it would comply with ICE. Last year, ICE detained just 343 people from DeKalb, mostly people for whom the agency had a warrant. Neighboring Fulton County, which also has a large immigrant population, detained 210 people at ICE’s behest. Together, that’s nearly 1,800 fewer people than ICE plucked from the Gwinnett County Jail in the same year.

On the day I visited his home last summer, Edy was running late, so he decided to make an exception and drove to work. When he wasn’t back by 4:30 p.m., Gaby started calling him every few minutes. “This is the thing I hate the most,” she told me as we sat in the living room of their apartment on Buford Highway, the thoroughfare between Atlanta and Gwinnett County. “Every time my son or Edy drive to Gwinnett, I can’t really relax until they’re home.” At 5:15, the front door opened and Edy walked in. There’d been traffic, he said. He told me quietly that the drive back from work had been terrifying. Police were everywhere, and all he could think about was getting stopped and not seeing his kids again. He sat down at the kitchen table and cried.

The costs of taxis were accumulating so much that after we met, Edy and his coworkers, almost all of them undocumented immigrants, convinced their boss that their next job should be outside of Gwinnett County. But the new work was in South Carolina. Every Sunday, Edy and his coworkers rode there with a licensed driver. On Friday they came back to Georgia. “I wish he didn’t have to leave every week,” Gaby told me. “But it’s better than driving to Gwinnett.”

For many immigrants in the county, avoiding ICE means avoiding the cops under any circumstances. Monica, who was being held in the Irwin County Detention Center with Ciru, had lived in Gwinnett since she was 6. Yet she’d long felt that she could not seek help from the police or any local authorities. She married an abusive man but refused to call the police because she is undocumented and he is a citizen who could sponsor her for a green card.

In late March, Monica and her husband got into a fight. This time, she said, when he attacked her, she fought back, and he dialed 911 to report an assault. The Lawrenceville officer who showed up cuffed Monica and took her in. A judge granted her bond, but she wasn’t allowed to leave the Gwinnett County Jail. Instead, she was moved to ICE detention in Irwin County. “This is just how it is if you’re illegal,” Monica said to me when we talked. “There’s nothing you can do about it.”

In early June, Carolina Ciru was deported to Honduras. Citing an old drug offense, ICE had refused to release her so she could handle her immigration case from home. Speaking on the phone from her sister’s house in Puerto Cortés, the town she’d left two dozen years earlier, Ciru said that until the moment she was boarded onto an airplane she hadn’t believed that she’d be kicked out.

“I feel betrayed. I have spent my entire life there,” Ciru told me. “I have worked there, I have children, we bought a house there, my children are from there, and because of the racist system that is there, I am gone.”

Ciru’s fears about what would happen to her family if she were expelled had started to come true. “I literally can’t really see how we are all going to survive without her,” Ciru’s daughter, Valerie, told me. “We were keeping everything going but she was at the center.” Valerie had to quit her job to take care of her autistic brother, David, and her own two kids. Ciru’s partner, Gabriel, had decided to send his twin stepchildren to stay with their aunt in Florida because he had to work and couldn’t take care of them while school was out due to the coronavirus.

On a recent afternoon, David walked out of the house alone and wandered up the road—he’d left to find his mother. On the walk, he had a seizure. The police brought him back home. Gabriel apologized for leaving him unsupervised. “I told them that he is usually with his mother, but that she is gone.” An officer asked where she had gone. He replied, “Immigration got ahold of her, because she was pulled over by the police.”

This story was reported in partnership with Type Investigations.

Notes on data methodology: In examining this data from Gwinnett County, our goal was to determine how many people were placed on ICE holds after being charged with minor traffic violations. We classified each offense a person was charged with either as a minor traffic offense, driving under the influence of alcohol or other substances, or other charges. Minor traffic offenses included charges such as driving without a license or insurance, speeding, broken headlights, and failure to use seatbelts. This list did not include any charges that involved physical harm, such as hit and run incidents. The category of other offenses included charges such as aggravated assault, but also nonviolent charges such as probation violations or failure to appear in court. Some people were charged with multiple offenses at once. We categorized these cases by their primary, or most serious, charge. For example, if someone was charged with a broken taillight and drunk driving, we counted them under DUI. If a person was simultaneously charged with DUI and aggravated assault, we counted them under other.