The simple act of breathing has been a challenge for residents of the Glades, a small rural community in Palm Beach County, Florida, for as long as 13-year-old Kil’mari Phillips can remember.

In fourth grade, Phillips’ teacher always kept the classroom’s blinds closed so her students wouldn’t see the fire. One day, she forgot.

“Do you see this?” a classmate, seated by the window, asked Phillips. “Am I crazy?”

Even from the far side of the classroom, Phillips could see giant flames engulfing acres of sugarcane fields outside.

“That’s when everybody started screaming,” Phillips remembered. Students from other classrooms rushed in when they heard the cries from down the hall. “Everybody thought they were gonna die.”

The Palm Beach County school year coincides with the seasonal agricultural practice of sugarcane burning. Before harvesting, leaves around the cane are ignited and burnt off like newspaper, revealing the sugar-rich stalks, which are about 70 percent water. This decades-old practice fills the air with smoke, soot, and ash. The result is the kind of particulate matter pollution that has been linked to a litany of adverse health effects — including, most recently, a heightened risk of dying from COVID-19. In June, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that jurisdictions consider suspending agricultural burns during the pandemic. Nevertheless, massive burns in the Glades continued throughout this spring’s harvest season and look poised to resume in October.

Phillips knows that the burning season’s begun when her breathing gets more difficult and her friends’ asthma flares up. It’s become a marker of time.

“It became so normal to us because it’s been happening all our lives,” she said.

Plumes of black smoke rise from sugarcane burns near Clewiston, Florida.Image: Patrick Ferguson, Sierra Club Organizing Representative for The Stop Sugar Field Burning Campaign

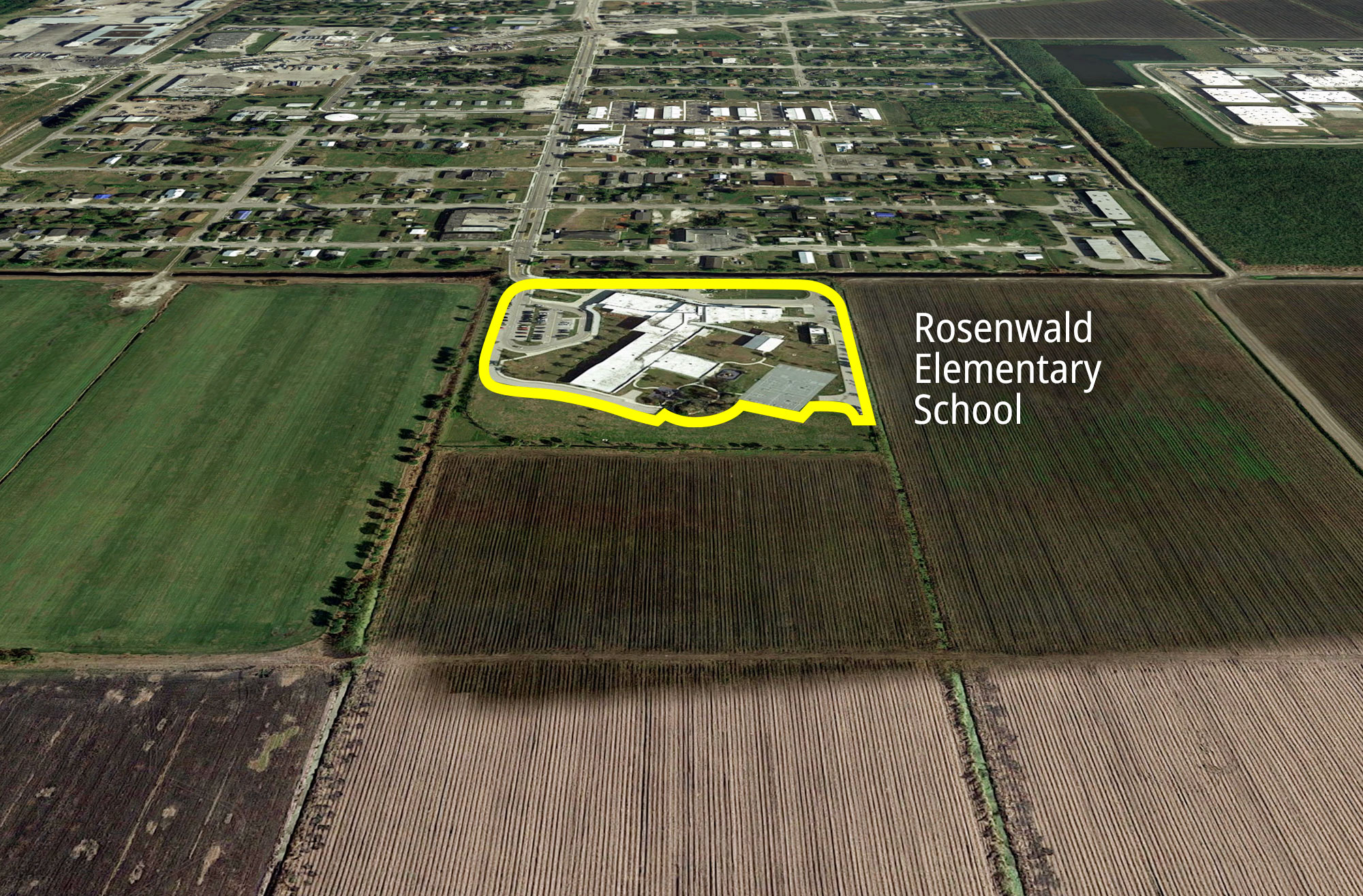

Phillips has since learned that her school district itself facilitates the harvest, leasing a sugarcane field adjacent to Rosenwald Elementary School in the town of South Bay to U.S. Sugar, one of the biggest sugar producers in America. About a hundred yards from Rosenwald — which Phillips attended from 2011 to 2017 — 7.8 acres of cane are processed during the harvest season, despite widespread concerns about dramatic, polluting burns like the one that terrified Phillips and her fourth grade classmates. (A U.S. Sugar representative said that “internal protocols” prevent burning from taking place on its nearby acreage during school hours — and that those protocols have been in place for more than a decade.) According to the latest lease, signed in 2017, U.S. Sugar pays the school district for the cane grown on the land and offers students “opportunities” in agricultural education.

Pollution from the seasonal burn spreads far beyond Rosenwald. Two miles away at the Hattie Fields preschool, 4-year-old Kennedy McKenzie’s asthma attacks leave her sick for two weeks out of every month during the school year, according to her mother, Letoni Moore. Five miles down the road from Rosenwald, in Belle Glade, former school nurse Anne Meehan had to stock a half dozen nebulizers in her closet to treat sick students every year before she retired in 2001. The devices were in use “all day long,” Meehan recalled.

Ten miles north, in Pahokee, students have carried trash bags over their heads to protect themselves from falling ash when they walk to school, according to Mariya Feldman, a former teacher. Theresa Staley, another former teacher, said she suffered such strong allergic reactions that she had to quit her job and move.

Image: Patrick Ferguson, Sierra Club Organizing Representative for The Stop Sugar Field Burning Campaign

There is clear scientific evidence that sugarcane burn emissions are hazardous to human health. As a result, most other states and countries that employ the method are working to phase it out in favor of mechanical harvesting processes. The archaic practice persists, however, in the rural towns of the Glades, where about a quarter of the nation’s sugarcane is produced.

The community is located just 40 miles from Mar-a-Lago and the ostentatious wealth associated with coastal Palm Beach County, where ornate and gilded mansions rise out of the ground instead of acres upon acres of cane stalks. The small towns that sit just off the southern shore of Lake Okeechobee are a world apart. The largest town, Belle Glade, is known as “Muck City,” in reference to the marshy land where sugarcane grows. While Palm Beach County is majority-white, Belle Glade is 60 percent Black and has a median household income that is less than half of the county’s overall. More than 40 percent of its residents live in poverty. Besides sugarcane, the Glades has exported a bumper crop of elite football players: NFL All-Pro Fred Taylor, Super Bowl MVP Santonio Holmes, and first round draft pick Kelvin Benjamin. Some attribute this athleticism to the fast-paced practice of hunting rabbits that rush out of the sugarcane fires.

The most unique features of the Glades are the giant flames accompanying the seasonal burn. A Sierra Club analysis of Environmental Protection Agency data estimates that the practice releases over 3,000 tons of hazardous air pollutants in the region every year, including carcinogenic chemicals like formaldehyde, benzene, and acenaphthylene. According to a 2016 study by researchers at Florida International University and the University of California, Merced, particulate matter pollution in the area was 15 times greater during the harvest season than it was at other times of the year.

Belle Glade residents wearing masks walk down a street off of Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard, as COVID infection rates in Florida reach record highs.Image: Jerry Rabinowitz

It’s no surprise then that a pandemic involving a respiratory disease would take an outsized toll on this community. The mortality rate from COVID-19 is nearly 80 percent higher in Palm Beach County than it is in Miami-Dade County, which has more than three-and-a-half times the caseload. Infection rates have been high not just in densely populated urban areas, but also in the particulate-choked Glades, where documented infection rates in some zip codes have been nearly three times higher than Palm Beach County’s rate overall.

The seasonal burn casts a long shadow over the Glades. The hoods of cars are faded due to ash buildup and nebulizers are ever-present in the community during the harvest season. Thousands of people in the region are employed by two of the biggest national sugar producers — U.S. Sugar and Florida Crystals — in a region that has suffered from high unemployment for decades. The sugar growers also fundraise for charitable causes, securing food, clothing, and household supplies for residents.

Public agencies at the county, state, and federal level have declined to phase out sugarcane burning, despite growing concerns about the adverse health effects of the practice expressed by both public health researchers and Glades residents themselves, as well as a class action lawsuit currently underway in the region. This neglect has left this low-income, predominantly Black community acutely vulnerable to respiratory illness.

A yearlong joint investigation by Grist and Type Investigations has found that the School District of Palm Beach County has leased the land adjacent to Rosenwald Elementary to U.S. Sugar for harvesting since 2002, despite consistent concerns raised by parents, students, and teachers about the effects of the burn; that the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services has for decades maintained discriminatory zoning rules that ban burning only when smoke drifts into wealthier areas of the county; and that public officials have referred resident complaints about the burn to the sugar industry itself.

A sign near a Florida Crystals plant south of South Bay, Florida, touts the brand’s commitment to organic products and green energy. Florida Crystals and Domino are two subsidiaries of West Palm Beach-based American Sugar Refining, Inc.Image: Jerry Rabinowitz

On a windy afternoon last fall, Phillips sat on her front porch with a young puppy in her lap, just 300 feet from Rosenwald and its fields of fire, momentarily resigned about the noxious air quality in her community.

“They’re killing people by doing this,” she said. “It’s taking innocent people’s lives for no apparent reason.”

‘A Fair Deal’

The incident in Phillips’ fourth grade classroom was not the seasonal burn’s most extreme intrusion into Rosenwald. On February 6, 2008, plume after plume of smoke billowed into the school. Administrators faced a dilemma when deciding how best to respond, according to internal correspondence: “Would the evacuation expose students to even more smoke from the sugar can [sic] burn or would keeping them in the school expose them to less smoke than the evacuation?”

By the end of the day, six students had been hospitalized and nine more had been treated by paramedics on-site.

As the community grappled with the fallout from the emergency, it was not widely known that the school district was actively collecting revenue from growers starting fires like these. Six years earlier, Rosenwald had quietly become the hub of a partnership between the sugar industry and the Palm Beach County School District.

The month before the incident, in fact, the school board was considering renewing the pact. “The question we may get now from the Board is whether this is a good/fair deal,” wrote a lawyer for the school district to another official in an email dated January 9, 2008. But at the school board meeting two weeks later, Joseph Moore, the district’s chief operating officer at the time, recommended the lease be renewed. The estimated revenue was projected to be $7,000 per year over the next five years. The safety and health of students was not mentioned in any internal correspondence provided to Grist and Type Investigations after a public records request, and the school district’s lease renewal with U.S. Sugar ultimately took effect three weeks after the evacuation.

Sugarcane ash covers the hood and windshield of a car in the Glades.Image: Patrick Ferguson, Sierra Club Organizing Representative for The Stop Sugar Field Burning Campaign

Claudia Shea, director of communications for the School District of Palm Beach County, did not respond to questions sent over several months about the district’s lease with U.S. Sugar; complaints from teachers, parents, and students about health concerns regarding the burn; or allegations by teachers that they are discouraged from speaking against cane burning at school. Shea ultimately provided a statement saying that, because agriculture is the primary land use in the region, it is impossible to locate schools “not in immediate proximity to these agricultural operations.” Shea also said that “the School Board has no authority to regulate agricultural activities of the region” and that the federal, state, and local agencies tasked with permitting and regulating the burns “ensure a healthy learning & working environment” at district schools.

Initially, the lease agreement also included an educational program called Sharing Our Agricultural Roots (SOAR) that helped students plant gardens of cherry tomatoes, broccoli, cabbage, and spinach. “Far beyond the educational aspects of what school gardens contribute is the self-esteem that they provide,” reads a program description from 2011, which was provided Grist and Type Investigations in response to a public records request. The description does not note the fact that the burn curtailed the amount of time that students could spend outdoors, tending to these gardens.

The hazards that the seasonal burn brings Rosenwald and its students are openly acknowledged by some stakeholders. On its website, the architecture firm contracted by the Palm Beach County school board to modernize Rosenwald emphasizes that its new design prevents students from having to walk outside during the school day: “Sugarcane fields are burned sending hazardous pollutants into the air. The heavy smoke and ash prohibit outdoor play, keeping the children inside throughout the school day many times during the year.”

The school district has also budgeted for an extra janitor to clean the “ash and muck” at Rosenwald and 11 other schools in the Glades. Teachers and students throughout the region say that the smoke is an ever-present concern. When Brittany Ingram, a former teacher at Belle Glade Elementary School, asked her students what would improve their community for a class assignment, she recalls several students writing “clean air” in their journals. In March 2017, she decided to distribute flyers around the school to raise awareness about a community event calling for mechanical harvesting as an alternative to the burn. Soon after distributing the flyers, however, she says she was reprimanded by her supervisor.

Rosenwald Elementary School in South Bay is adjacent to nearly eight acres of sugarcane stalks. Students are often unable to play outside due to smoke from sugarcane burns.Image: Google Earth

At Pahokee Middle School, Dayan Martinez became accustomed to always seeing a handful of asthmatic students sitting in the main office while their peers were exercising during P.E. Martinez taught sixth grade meteorological science, but he stayed quiet when it came to discussing the clouds of smoke that would form outside of his own classroom. He wasn’t a Glades native, and was wary of raising concern about a practice so deeply associated with many residents’ livelihoods.

“Sadly, you don’t ask many questions sometimes,” he said.

Rosenwald’s current lease with U.S. Sugar, signed in 2017, expires in 2022. The lease renewal estimated that revenue increased slightly, from $7,000 to $12,000 every year. The SOAR gardening program was omitted from the most recent agreement. Instead, it states that the sugar company’s partnership benefits Rosenwald by “affording them the opportunity to be involved in agricultural events sponsored by U.S. Sugar.”

‘We Already Know’

Dozens of scientific studies link exposure to sugarcane smoke to a litany of adverse health outcomes, according to a literature review currently being conducted by researchers at the University of Florida’s department of environmental and global health. Among the maladies associated with the practice are chronic kidney disease and increased risk of fetal death.

“We already know that particulate matter is hazardous,” said Eric Coker, a professor in the department. “Particulate matter can actually affect almost every organ system in the body, from neurologic to cardiovascular to respiratory to reproductive.”

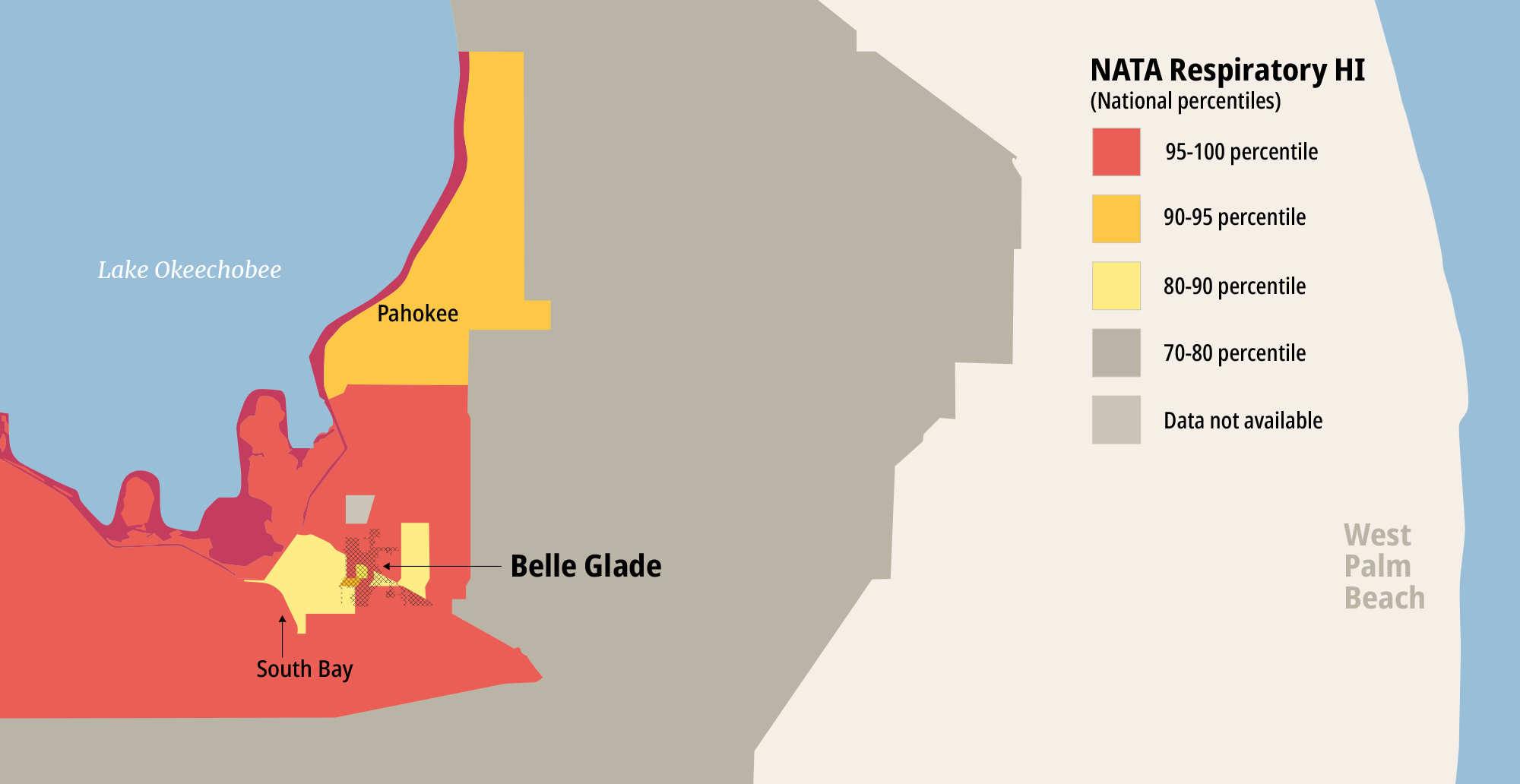

Thanks to months of sugarcane burning every year, much of the Glades region falls within the top 20th percentile of an EPA index of the most hazardous areas in the U.S. for respiratory health. Image: Grist / EJSCREEN

As a result of these hazards, sugar-producing regions in Brazil, India, and Thailand are taking steps to phase out the burn. In Louisiana, growers primarily use mechanical harvesting, instead of burning, to harvest their crop. Palm Beach County is an anomaly. And because of this, Glades residents say that they suffer unduly from ailments like asthma, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer.

The regulation of sugarcane smoke in Florida involves four different federal, state, and county agencies that permit and monitor the burns and air quality. Ultimately, they’re tasked with ensuring that pollution does not exceed federal air quality standards. The EPA’s environmental justice mapping tool, which combines demographic and environmental indicators, places the Glades within the 80th to 98th percentile in its index of the most hazardous areas for respiratory health in the U.S. However, even though the respiratory risk in the Glades is higher than in most of the country and surrounding areas, it still doesn’t violate legal standards established under the Clean Air Act, according to the EPA. Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection, which is responsible for monitoring the state’s compliance with the Clean Air Act, also said that Palm Beach County meets national air quality standards. In a recently filed class-action lawsuit, residents dispute those conclusions.

Smoke from a sugarcane burn appears over a strip mall in Belle Glade.Image: Patrick Ferguson, Sierra Club Organizing Representative for The Stop Sugar Field Burning Campaign

In 1978, Palm Beach County passed the Environmental Control Act, which authorized county commissioners to regulate pollution. But agricultural industry stakeholders insisted on and were granted an exemption for pollution generated by their activities, according to Jim Stormer, who worked on the county health department’s air pollution control program from 1990 to 2015. Even if sugarcane burning created air pollution, the county had no power to force sugarcane farmers to comply with the law.

In the 1990s, the EPA introduced a new standard to measure hazardous particulate matter in the air: PM 2.5. This type of particle, named for its size, is especially harmful because it can get lodged deep in the lungs. Scraping together grants, Stormer teamed up with researchers at the University of Florida to collect data detailing the chemical composition of sugarcane burn emissions to submit to the EPA. Stormer also offered support to researchers at Florida International University in determining the percentage of hazardous emissions in the Glades that could be attributed to sugarcane burning. One of those studies found that ambient levels of harmful particulate matter increase 15-fold during the harvest season — and that a significant portion of that pollution could be sourced definitively to sugarcane burning.

But without an epidemiological study that shows a causal link between the burn and the adverse health effects reported by Glades residents, regulation is unlikely, Stormer said.

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, or FDACS, did choose to regulate the practice nearly 30 years ago — but only in instances when the burn’s smoke drifts into Palm Beach County’s more densely populated and wealthier regions. On a typewritten report dated September 1992, the department mapped the county into four zones, spanning from the coastal Zone 1 in the east to Zone 4, which encompasses the Glades and other western parts of the county.

When the wind blows toward the more urban areas to the east, the agency prohibits sugar growers from burning, forcing them to either wait to harvest or use the alternative method of “green harvesting,” where leaves are mechanically removed instead of burned off. Zone 4 is currently the only area where burning is always permitted, no matter which way the wind blows.

A recent burn in Belle Glade fills the sky with soot and ash.Image: Patrick Ferguson, Sierra Club Organizing Representative for The Stop Sugar Field Burning Campaign

“You’ve got 1.4 million people living in Palm Beach County but only probably 30 or 40 thousand of them in Belle Glade,” said Rick Roth, a sugar farmer and state representative, explaining why mitigation measures don’t apply to the Glades. “That’s why we have the regulations that try to minimize the amount of sugarcane soot going east.”

He added that it takes 30 percent longer to harvest sugarcane mechanically, rather than using the burn: “It’s really a matter of trying to just do it as cheaply as possible.”

Outside Contacts

For the past five years, a handful of Glades residents have gathered regularly to address the dangers of the harvest burn. A “Stop the burn” sign greets them at the door when they arrive at the nondescript office on Main Street in Belle Glade.

“We are inching too slowly,” said Kina Phillips at a meeting last August. She had come straight from her job as an office coordinator for a local doctor and was still wearing her peach-toned owl-print scrubs. Kina, Kil’mari Phillips’ mother, is at the center of the fight against the burn in the Glades and has spoken at conferences about her concerns for her community.

In 2015, Shanique Scott, an entrepreneur and the former mayor of South Bay, where Rosenwald Elementary School is located, contacted the Sierra Club about setting up a local campaign that could pressure the sugar industry to be better neighbors and minimize the impact of the burn. Scott teaches dance and had long watched her students fall ill, huddling over nebulizers in class during the peak winter months of the burning season.

Sugarcane fields line the roadway leading into the town of South Bay.Image: Jerry Rabinowitz

Glades residents like Scott and Kina Phillips found an eager out-of-town ally in Steve LaPorte, a retiree who spends his days boating nearby. LaPorte was fed up with cleaning ash off the boat he keeps on a freshwater creek near Lake Okeechobee, about an hour’s drive west of the Glades. Since 2014, LaPorte has painstakingly documented the burns and smoke plumes he sees on any given day.

“I’m personally fed up,” LaPorte said. “I just don’t understand how [Glades residents] can put up with this, being targeted on a daily basis.”

LaPorte and Scott have contacted local government agencies multiple times over the years to inquire about particularly smoky burns. On some occasions, public officials have turned around and shared their inquiries with paid representatives of the sugar industry.

Scott met with FDACS officials at a local restaurant in November 2017 to inform them of one such event, in which she filed a complaint to the Florida Forest Service (an agency FDACS oversees). She says she was subsequently contacted by U.S. Sugar to follow up on the complaint. According to notes from that meeting provided by the Sierra Club, officials said that they had no idea how her phone number was shared, and that the incident would be investigated. (A spokesperson for FDACS told Grist and Type Investigations that the department has no information regarding an investigation into the incident, since it happened under a previous governor’s administration.)

It wasn’t just the forestry office that appeared to be sharing resident complaints with industry. In April of the following year, LaPorte asked the health department to measure the ash in his neighborhood. Randall Miller, a former Department of Health employee then working as a consultant, wrote him back in response. Miller explained that he was reaching out on behalf of his client, the Florida Sugar Cane League, which represents South Florida sugar farmers.

Smoke from a sugarcane burn darkens a clear sky near South Bay.Image: Patrick Ferguson, Sierra Club Organizing Representative for The Stop Sugar Field Burning Campaign

“They are interested in trying to better understand your concerns about pre-harvest burning and to see if we can determine how you and your community may have been affected yesterday,” Miller wrote. LaPorte emailed the health department requesting that his information not be shared with “outside contacts.” A health department spokesperson said they had no knowledge of how LaPorte’s request was shared.

Miller can accurately claim to have spent decades monitoring the burns. He worked at the Palm Beach County Department of Health with Jim Stormer from 1981 to 2016, according to promotional materials for his business. He founded Miller Environmental Solutions within a year after he left government, and the sugar industry soon became one of his clients.

In July 2017, Miller and U.S. Sugar collaborated on a presentation “combatting the Sierra Club’s anti-cane burning efforts” in Palm Beach County. It claimed that sugarcane burning was a well-regulated practice and that the county’s air quality was good. Judy Sanchez, the communications director at U.S. Sugar, shared the PowerPoint file with a health department official from a neighboring county, asking if a similar presentation would be effective in their community.

The attached slides claimed that there were zero complaints about sugarcane burning during the 2017 harvest season. In fact, three such complaints were made to FDACS from fall 2017 to spring 2018, according to sugarcane smoke and ash complaint logs obtained by Grist and Type Investigations through a public records request.

In a written statement, Sanchez wrote that the presentation offered an overview of the regulatory framework in the region, and that the Glades region “enjoys some of the best air quality in the state.” It was developed, she added, “as part of regular and ongoing communications/engagement with our neighbors and our community. ”

Local activists in the Glades have reported that their complaints filed to Florida government agencies have been referred to the sugar industry, including Clewiston-based U.S. Sugar. Image: Jerry Rabinowitz

The Palm Beach County Department of Health said that it has not incorporated any presentations from Miller into the resources it provides to the community. Miller, who also defended sugarcane burning and the Glades’ “very good, above-average air quality” in a 2019 op-ed for the Palm Beach Post, declined to comment.

‘The Hazard Zone’

In June 2019, the Berman Law Group, a firm based in nearby Boca Raton, filed a class-action suit against sugar companies operating in the Glades, alleging that the pre-harvest burn is causing significant damage to residents’ health and property. Local power brokers have been quick to condemn the effort.

“We see this lawsuit for what it really is: a money grab that attempts to pit neighbor against neighbor and harm our way of life,” read a combined statement from the mayors of Pahokee, Belle Glade, South Bay, Clewiston, and Moore Haven posted to Facebook.

This June, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint alleging that smoke from the burn exposes them to a wide variety of hazardous or carcinogenic pollutants at concentrations that exceed national air quality standards throughout seven different communities affected by the burn. The complaint calls these areas “The Hazard Zone.”

Smokestacks overlook fields near the Sugar Cane Growers Cooperative of Florida sugar-processing facility in Belle Glade.Image: Jerry Rabinowitz

Over five years of air modeling conducted by experts hired by the law firm, PM 2.5 levels in the Glades exceeded national air quality standards across 16.3 percent of the roughly 5,000-square-mile region they modeled, the complaint states. In one extreme case, Pahokee’s levels measured 5.7 times the national standard.

If the suit proceeds into the discovery phase, the plaintiffs also say that they will present new epidemiological data showing that Glades residents are 2.5 times more likely to be hospitalized for respiratory illness, compared to Florida residents overall.

Both the lawsuit and the COVID-19 pandemic — and in particular the burgeoning connection between high levels of particulate matter pollution and elevated mortality rates from the virus — have increased pressure in the region to shift over to mechanical harvesting. On April 27, more than 200 environmental groups, religious organizations, local businesses, and other organizations called on FDACS Commissioner Nikki Fried to end the pre-harvest burn in the Glades.

While Fried has not echoed this call, in October 2019 she announced what she said were the first major changes to sugarcane burning regulations in nearly three decades. The second phase of this effort was announced earlier this month. It includes the implementation of a training program for burners and a revision of the zones set up in 1992, which allowed burning to take place in the Glades no matter which way the wind blows. This change, Fried’s director of communications said, will “reduce potential smoke impact to all communities.” The Sierra Club, however, argued in a statement that the changes appear to “do little to protect Florida residents living in and around the Glades.” The revision will take effect in January 2021.

The burn appears likely to proceed as usual this fall, despite Fried’s reforms, the class-action suit, and a still-raging pandemic.

Still, opponents of the practice are not giving up. At a virtual town hall hosted by the Poor People’s Campaign in May, Kina Phillips noted her concern for her daughter Kil’mari’s future in explaining why she’s still trying to end the burn.

“A lot of people ask me why I’m in the fight,” Kina told the virtual audience of nearly 100 people. “I had to fight because I didn’t want to leave that burden on my kids and generations to come.”