Geology, as a discipline, often involves the study of “deep time”: the profound magnitudes of history, a billion-year continuum on which continents drift and break apart, and the climate sways from ice to fire and back again. But the work at USGS can also come down to crucial moments, not so much gee-whiz as oh-shit: A seismic wave from far away hits a laboratory instrument, signaling the onset of an earthquake, and there’s a narrow interval in which to issue an alert. “You might have 20 seconds or 120 seconds, it isn’t much for you and I,” Reilly told the audience at AGU. But for a gas utility, this could be the margin needed to shut things down and prevent a series of explosions. The same is true for tornado warnings, flood alerts: Every minute, every second, counts.

That’s where Reilly seems most comfortable—in the zone of near and consequential outcomes, measured and assessed with extreme precision. As a logistical engineer at NASA, he’d been responsible for multi-staged tasks that require months of planning and for which the margin of error could be razor thin. “You get one shot to get it right, and if you don’t get it, you’re stuck,” says Danny Olivas, who was Reilly’s partner for his eight-hour spacewalk in 2007. More serious mistakes, of course, could be fatal. On his first mission in 1998, Reilly was in charge of choreographing the transfer of thousands of pounds of supplies and equipment to the Mir space station. “He did that just masterfully,” says Terry Wilcutt, the flight’s commander. “He can take a complex task and break it down into executable pieces and then it just goes smoothly.”

James Reilly, NASA astronaut, in 1997.Image: NASA

But what USGS scientists do is in a sense the opposite of logistical engineering: Much of the agency’s research is based on stitching together a diverse array of data and observations, both in the lab and in the field, in order to better understand the planet. That’s true whether scientists are estimating petroleum reserves in the Permian Basin or the rate at which glaciers are melting in Montana. Doubt is often pervasive, and USGS scientists must think very carefully about how to address it. “You have to be comfortable with the uncertainty, or at least not paralyzed by it,” says one former scientist at USGS.

Reilly’s arrival at the agency brought a clash of cultures, then, between the spacemen and the modelers. “He really cannot grasp that dealing with climate science is not an engineering problem,” says the scientist, who has worked closely with Reilly.

Reilly, who is in his early sixties, holds a PhD in geosciences, but he’s had no previous management experience in federal government nor was he a very active member of the research community. Indeed, before he was appointed by President Trump, few at the agency had even heard of him, according to interviews with USGS employees. Following his stint at NASA, he served as dean of the school of science and technology at a for-profit, online university and started a consulting firm; all while leaving little public record of his political leanings or personal beliefs. At the time of his US Senate confirmation hearings, one headline stated, “Nominee to lead USGS is hard to read.” Reilly even cracked a joke about his atypical career path at the Geological Society meeting, speaking as the first astronaut ever to lead the agency. “How did I get either of those jobs?” he asked. “I have no clue and I’m not asking.”

In fact, Reilly’s name had been floated as a possible candidate by his good friend Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, another former astronaut who happened to have contacts in the Trump administration. In addition to flying on the final Apollo mission, Schmitt has made a name for himself as an outspoken critic of climate science. In 2018, during a panel discussion, Schmitt was asked about his doubt that human beings are causing climate change. “There is no evidence,” he said. “There are models. But models of very, very complex natural systems are often wrong.”

Model-bashing has been a favorite pastime among those who deny that humans are the primary drivers of climate change. This makes perfect sense, since it’s the models that dictate action: They show what might happen if we continue down our current path and hint at how we might avoid it. If the models can’t be trusted, or if their scope is limited, then the future is unknowable; and if the future is unknowable, then what’s the case for regulation? That’s why the most heavily polluting industries have been incentivized to focus on climate models’ flaws, in much the way that commercial interests have tried to shower doubt on research into the long-term health effects of asbestos, smog, and cigarettes (among many other things).

Indeed, a network of conservative think tanks, including the Heritage Foundation and the Heartland Institute, have consistently pushed the notion that climate models are defective, which has in turn become a central talking point at the White House. In 2018, the Heritage Foundation told The New York Times Magazine that 66 of its employees and alumni had joined the federal government. Schmitt happens to be a former board member and policy adviser at the Heartland Institute. William Happer, a professor emeritus at Princeton who has compared climate models to Enron’s accounting practices—and described those who believe in them as members of a “cult”—also has close ties to Heartland, and was, until recently, a top Trump adviser.

Reilly’s own efforts to constrain the use of models have been insistent, and his steadfast aversion to the long view seems also to apply to USGS itself. Several government employees I interviewed for this story said they’d gotten the sense that Reilly views climate models as the mishandled tools of a broken, antiquated institution—and one that’s filled with broken, antiquated researchers. More than a dozen current and former employees told me that his tenure at the agency has been both morale-crushing and hostile, especially for the agency’s longest-serving scientists. These claims may be addressed in a report focused on Reilly from the Inspector General’s office at the Department of the Interior that is set to be released later this month. According to multiple sources who served as witnesses for the IG, Reilly has effectively purged the agency of senior-level employees who had been close to his predecessor; while elevating a former NASA employee to serve as his deputy director, and intervening to install a former astronaut and friend, C.J. Loria, as director of the Earth Resources and Observation Science Center. “There are people in the survey whose careers he has destroyed,” says one senior USGS employee interviewed by the IG’s office.

A separate report, related to an age-discrimination case, has already been completed by the department’s Office of Civil Rights. In 2019, a 63-year-old woman who had worked for the federal government since the early 1980s complained that Reilly had ordered her duties stripped the year before, because he knew she planned to retire and wanted to “speed it up and make it happen.” Reilly denied the allegation, but the Office found in the employee’s favor at the end of August and said USGS must take corrective action and provide documentation of whatever disciplinary measures are adopted. (In response to requests for comment about the Office of Civil Rights report and the IG report, a USGS spokesperson provided the following statement: “Independent, unbiased science is foundational to the USGS and critical to the 21st Century global challenges we face. Dr. Reilly has endeavored to uphold scientific principles by strengthening operational standards, challenging norms, encouraging internal debate and pushing the organization to greater heights to meet those challenges.”)

Several witnesses in the age-discrimination case told investigators they’d heard Reilly grouse about all the “gray-haired” people at the agency, and imply that younger people should be hired in their place. The director had even said as much in public. A few days before Reilly spoke at the AGU meeting, he’d been asked to sign a stack of 40-year certificates, honoring his veteran employees. “The good news is, people love their jobs, they come to work and they are still there,” he told the audience during his conference presentation, in reference to that paperwork. “The bad news is, they’re still there. No, I’m kidding!”

Meanwhile, about 20 scientists from the upper echelons of USGS had convened with Reilly on the sidelines of the conference. Many were meeting the director for the first time. But he seemed less interested in honoring their years of service than lamenting the absence of younger scientists, according to a person who was present. That person recalls that Reilly looked around the room, and noted that the agency is just too old. (Reilly declined to comment on this episode.)

“This was the moment, when he’s sitting there with the senior scientists … and telling us we were redundant and useless. That’s when I realized we were really screwed,” the attendee says. “That was my light bulb.”

In May 2019, at a meeting with his G-7 counterparts in France, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency made a provocative announcement. It was tucked into a joint statement of environment ministers released after the summit, just beneath a recap of the Trump Administration’s plan to withdraw from the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. The US pledged to “re-examine” climate modeling on an ongoing basis, it said, in such a way that “best reflects the actual state of climate science in order to inform its policy-making decisions.”

A government spokesman later clarified, “Currently, there are no specific efforts [of this kind] underway at EPA.” As for specific efforts of this kind in other parts of government, the spokesman didn’t say.

In fact, the language from the summit closely mirrored Reilly’s thoughts on what to do at USGS. Hints of his proposal would come to light a few weeks later, when the New York Times published a front-page story saying that Reilly had ordered his agency to narrow its horizon for climate projections to 2040. In an all-employee email sent the next morning, and obtained by WIRED, Reilly disputed that account: “As you should know there has been no such directive given,” he wrote. The agency had embarked upon an effort to “develop and refine” how the Department of the Interior uses climate models for decision-making, the email said, and related guidelines would be issued soon. “In the meantime, keep doing the great work we do in the Survey and remember: science has no politics.”

But new reporting from WIRED and Type Investigations—including conversations with more than 20 current and former government employees, and a review of several hundred pages of internal documents—reveals a more extensive effort to reframe the way that USGS scientists use modeling in their research. It’s true there was (and is) no hard cutoff for projections: Reilly’s draft directive on the subject, circulated among senior staff this past July and obtained by WIRED, suggests that projections run to 2045, “as an initial assessment range.” Still, Reilly has made it very clear that he wants to keep the focus on that narrow frame whenever possible; and in pursuit of this agenda, he has overlooked the guidance of his staff scientists in favor of a highly-unusual relationship with an outside contractor.

The push appears to have begun soon after he was confirmed. According to emails obtained through a FOIA request, that’s when Reilly began laying the framework for a partnership with the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, a nonprofit consortium of colleges and universities that manages the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The center is one of several institutions that develop models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and other climate researchers. Reilly paid a visit to its Colorado campus during his second week on the job. By the end of 2018, USGS was in discussions with the consortium about a possible contract to review climate models.

As the details were being worked out, Reilly sought advice from the consortium on the internal policy memo that he’d prepared for Zinke, which floated his proposal for new, department-wide guidelines on the use of climate modeling. Every five years a team of USGS and NCAR scientists would evaluate the latest data to revise those models, the memo said. The idea would be to provide DOI with the tools needed to respond to climate change “within a statistically manageable range of possibilities”—i.e. on a 10-to-20-year horizon.

Scott Rayder, a former chief of staff at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who was then a senior adviser at the consortium, responded with his feedback. “This looks stellar,” he told Reilly. “I think this is a huge step forward.”

Three months later, on March 19, NCAR was awarded a non-competitive $40 million contract to advise USGS on a wide range of issues including “models, observations, computational resources, data services, and education and outreach.” Though the language in the contract is expansive—in theory it could encompass just about any USGS initiative—Reilly would, in private emails, clarify his interest. In a message dated May 7, he asked Rayder to confirm the scope of work: “Will this agreement cover and operate in a way to support our 60-month review of climate change models?” Rayder responded that he thought it would. (In a written statement, the consortium said Reilly’s memo was “consistent with the briefings he received from NCAR scientists.”)

According to multiple USGS sources Reilly’s handling of the memo violated agency norms. “It may have run afoul of regulations prohibiting the sharing of non-public information,” says Debra Sonderman, who was the procurement executive at DOI for nearly three decades before she retired in 2017. Policy memos, which USGS rarely drafts, are not typically shown to outside entities particularly during the early stages of their development. Members of the private sector are not supposed to be involved in their production, says Sonderman.

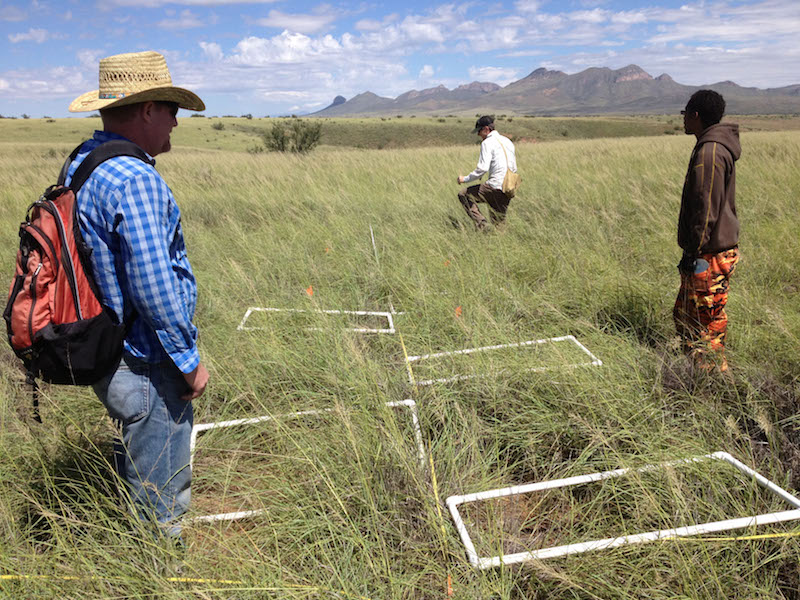

A USGS field crew measuring the density of grasses in southern Arizona. Image: Miguel Villarreal / USGS

The size of the contract is also noteworthy: According to federal contracting data going back to 2008, USGS has only worked with the consortium in charge of NCAR on a few occasions and for far smaller sums. Its largest contract with the consortium was a one-year, $60,000 research and development project in 2009. USGS said all federal regulations were followed in pursuing the non-competitive award.

A consortium spokesperson said the group’s researchers frequently provide guidance to federal agencies on a variety of climate-related issues. But the spokesperson added, “We do not necessarily know how our comments will ultimately be used, and whether a particular memo … is for internal policy or another purpose.”

In a written statement to WIRED, Reilly echoed what he’d written in his all-staff email, that he has not issued “any directive that restricts the development or use of climate models by USGS researchers or limits projections of climate impacts past 2040.” He also said, “USGS will continue to use all accepted models and scenarios” and to “assess the entire range of reference scenarios from best-case to worst case in its scientific studies.”

Yet when Reilly assembled a team of his own top climate researchers to draft a white paper on modeling in 2019, not long after the Times story was published, some within the agency understood it as a means of building scientific cover for a plan to narrow the time horizon. “We were all very much painfully aware of the 2040 thing,” says one of the scientists tapped for that assignment.

The white-paper team had frequent phone calls with Reilly as he tried to guide the process, and tried to explain the rationale for making long-term projections. Reilly wasn’t interested. “He didn’t want to understand it,” says the scientist who was on the team. “He wanted to justify his position.” During one exchange, Reilly asked the scientists to cut a relatively benign sentence that read: “To fulfill their missions successfully, natural resource managers often must consider future risks including those stemming from climate change.” In another, according to the scientist, Reilly raised questions about a graph showing a set of IPCC models and what might happen under different emissions scenarios—a version of the “Spaghetti Chart.” Reilly went into his spaceman spiel: He said there were so many variables going into these scenarios, the scientist recalls, that it would be impossible even to make a statement about them, let alone a policy decision. (USGS said that the agency’s fundamental scientific practices were followed during the development of the paper.)

This represented a fundamental misunderstanding of what these models are designed to do, according to that scientist. It’s not about making firm predictions of what will happen in the year 2100—of course you can’t do that. It’s about preparing yourself for the full range of potential outcomes, and understanding how they might depend on decisions that we make today. “You very clearly can say something,” the scientist explains. “You can say we are going to be significantly worse off if we don’t do something.”

The white paper, titled “Using Information from Global Climate Models to Inform Policy Making—The Role of the USGS,” was quietly published in June. Reilly’s meddling appears to have been shrugged off. The paper highlights the utility of modeled scenarios that project 100 years or more into the future. “Examining a range of projected climate outcomes,” it says, “is a recommended best practice.”

In late-October 2018, not long before Reilly gave his “who the heck am I?” speech to the AGU, an interagency fight broke out among some of the federal government’s leading climate scientists and administrators. The Fourth National Climate Assessment was on the verge of being released, and a set of political appointees were pressing for some last-minute changes. In particular, officials at NOAA, led by chief of staff Stu Levenbach, wanted to dispense with any broad-brush overviews of the report’s key findings, including italicized phrases such as “ climate change is expected to cause growing losses to American infrastructure and property,” and “climate change increasingly threatens Indigenous communities.” Instead, these officials argued, the summary should emphasize the full range of possible outcomes by enumerating them separately for each emissions scenario. (Levenbach declined to comment for this story and referred questions to the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy. OSTP did not respond to requests for comment.)

Some members of the advisory board for the US Global Change Research Program, which coordinates and oversees the National Climate Assessments, worried that the proposed changes would make the document much less useful and accessible for non-scientists. According to one member, the board felt that the changes pushed by Levenbach might also end up misleading readers on important points, such as the degree to which the assessment actually focuses on climate projections.

“It created some tense moments,” another board member told me. At that point, the program’s acting chair was Virginia Burkett, a USGS veteran of more than 30 years. Burkett is an internationally recognized climate scientist—she was part of the team that won the Nobel Prize for the IPCC report in 2007—and has always tried to keep her distance from political entanglements. “As a scientist,” she said in a 2014 interview, “I think you lose credibility if you become a table-banging activist.” But when the last-minute request for edits came in from NOAA, Burkett stood firm. “Virginia, as the chair at the time, you know pushed back pretty hard,” the board member said.

In the end, Burkett’s faction held the line and none of the requested changes were put into the report. But according to the senior USGS employee, Reilly was deeply dissatisfied with the process and the way Burkett handled it. (Burkett declined to comment for this story.) In 2019, he told Burkett that he would be replacing her as program chair. Her successor turned out to be Wayne Higgins, a NOAA climate scientist who had been involved in negotiating the requested changes on behalf of Levenbach. “She paid a big price for sticking her neck out,” said a former government scientist who was intimately involved in the Fourth Assessment. USGS said Burkett was replaced because it was time for another member agency to chair the research program.

Despite these machinations, and however much the Trump administration tried to spin the Fourth Assessment, they arrived too late to make a difference. Much of the work on that report had already been completed by the time Trump took office; and so—just like the climate curves on Reilly’s “Spaghetti Chart”—the short-term outcome was never really in question. It’s only by looking forward that one can spot the bigger dangers: The Fifth National Climate Assessment is due out in 2023, and if Trump is reelected, his Administration will get to shape what is arguably the most important policy document on climate change produced by the federal government. In the meantime, Reilly’s plan to re-examine—and perhaps restrict—the use of climate models will have had a chance to gestate further. And all along the way, the hottest-ever years on record will continue to accumulate. This past May, in the midst of the pandemic, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere surpassed 417 parts per million. It was the first time this has happened in at least three million years.

If Trump loses, though, then Reilly will almost certainly be out; and there’s no way to know for sure how the next administration—and the next USGS director—might approach these problems. That’s what happens when you’re doing geoscience on a political timescale: The future only lasts until the next election.