On March 28, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency-use authorization allowing the drug to be used in hospitals after disclosing potential risks. The FDA recommended careful heart monitoring and urged hospitals to use the drug “with caution” in patients with a history of heart problems — warnings underscored by the CDC and several leading medical organizations.

The New York State Veterans’ Home in St. Albans, QueensImage: Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

‘No Way in Hell’

New York’s health department did acknowledge in October that three of the four state-run veterans’ homes used hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin or zinc for COVID-19 patients for up to two months.

But, citing “public health law protecting patient privacy,” the agency declined to say which facilities or how many residents were given the drugs. It further declined to answer basic questions about St. Albans, such as whether the home has a heart-monitoring machine.

Other facilities have acknowledged the use of hydroxychloroquine, including the Long Island State Veterans Home in Stony Brook.

Run by the State University of New York, the home said in a statement that it administered the drug to 30 COVID-19-positive residents “after careful consultation with respective residents and their family members.” The facility said it “immediately discontinued” use of the drug in late April after the FDA issued a new drug safety warning.

To date, the state health department has reported 95 resident cases of confirmed COVID-19 at St. Albans, with 43 virus-related deaths, although a list leaked by staff and obtained by THE CITY identified 48 residents who died in March and April 2020. It is unclear how many of those residents received the drug cocktail or whether the death toll includes people like Hutcherson, who died primarily from heart failure.

Across New York, more than 13,000 nursing home residents have died from the virus since the pandemic began, according to the health department. That includes roughly 4,000 residents who died outside of the homes, a figure released only after a report by state Attorney General Letitia James documented undercounting by the Cuomo administration.

Some families interviewed for this story commended St. Albans, saying the staff took good care of the residents. But Parson and others contend that their loved ones should not have been given the experimental treatment due to their age and medical history.

“If they’d told me anything… I would have told him, you cannot give that to my father. He’s 93 years old,” Parson said. “There’s no way in hell I would have let them give my father that medication.”

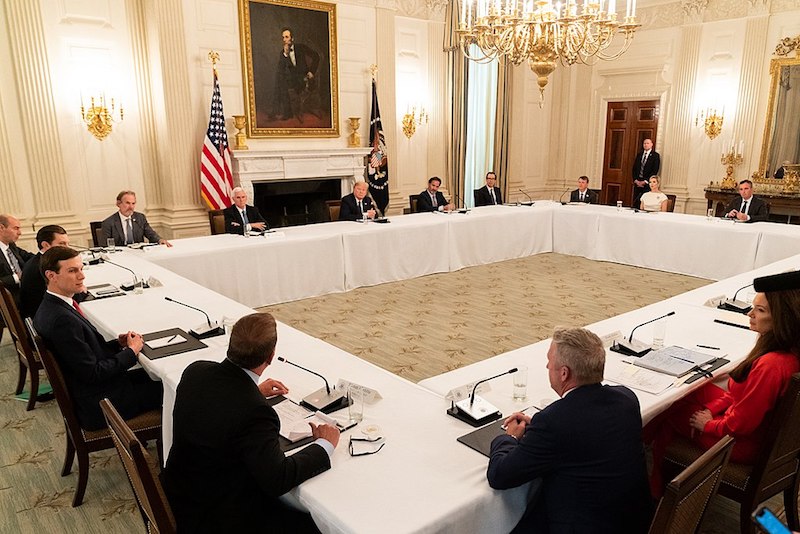

President Donald Trump meets with restaurant executives at the White House, May 18, 2020.Image: D. Myles Cullen/Official White House

Trump: It ‘Doesn’t Kill People’

The hype around combining hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin emerged in March 2020 when French doctors published a study in which six people who received the cocktail recovered from COVID-19. The study, which was not randomized or peer reviewed, did not address geriatric use but stated that “the cost benefits of the risk should be evaluated individually.”

Trump picked up on the results, tweeting on March 21 that the cocktail could be “one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine,” despite skepticism voiced by his own scientific advisors — including Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Trump would later announce that he was taking hydroxychloroquine as a preventative and declare that it “doesn’t kill people,” though he once cautioned that people with heart problems should avoid azithromycin.

Anecdotal reports of success, however thin, offered a glimmer of hope to New York, which had more active COVID-19 cases than any other state in the country.

On March 23, Cuomo, already facing 20,000 cases, signed an executive order allowing people who tested positive for COVID-19 to receive hydroxychloroquine in state-approved clinical trials.

“The president is optimistic,” said Cuomo at the time. “We don’t know, but let’s find out.”

Days later, a group of city and state politicians from Staten Island criticized the move as inadequate in a letter to the governor, noting that the order effectively banned the drugs from nursing facilities except for clinical trials.

Cuomo quickly amended the order, allowing use in nursing homes with subacute care units, such as St. Albans, and lifting the positive-test requirement. Cuomo’s office did not respond to questions for this story.

‘Possible Drug Toxicity’

It’s unknown what guidance, if any, the state gave nursing homes regarding how to administer the medications. Responding to a state Freedom of Information Law request, the health department was unable to locate any such guidance, advisories or requirements.

In an April 2 presentation for health care providers, the department acknowledged a “possible drug toxicity” for hydroxychloroquine.

World War II veteran James Hutcherson died at age 93.Image: Courtesy of Yvonne Parson

The FDA’s emergency authorization, issued the same week as Cuomo’s orders, raised similar questions about safety and efficacy. Two former FDA commissioners openly condemned the move, asserting that the lack of supportive evidence undermined the agency’s credibility.

But growing concerns did not stop the drug’s use. Nationally, new hydroxychloroquine prescriptions were more than three times higher last April, compared to the same month in 2019.

Some doctors, desperate for any possible aid, used both drugs until clear evidence emerged of their ineffectiveness.

One New York-based veterans doctor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly, said the possibility of benefit outweighed the risk. A geriatrician, who also declined to be named, said condemning such use equated to “Monday morning quarterbacking.”

Other doctors used hydroxychloroquine only with heart monitoring or refused to combine it with azithromycin because of the added risk.