Once, Valee Taylor and Renee Stewart’s family was among the largest Black landowners in North Carolina’s Orange County, a rectangle of farm country running north from Chapel Hill.

In the 1930s, after a life of sharecropping, the siblings’ grandfather, Berea “Burrie” Corbett, turned $40 worth of gold coins his parents had given him into a 1,300-acre tobacco farm in tiny Cedar Grove, becoming a pillar of the local Black bourgeoisie. He built a church and a school for the local Black community.

Taylor and Stewart had helped run the farm during high school and college. After careers in law enforcement and pharmacy, respectively, they decided to return to the family business. In 2009, aided by a loan from the US Department of Agriculture, they launched a high-tech aquaculture operation in a 10,000-square-foot building that stood where their grandfather once grew tobacco. Taylor Fish Farm’s organic tilapia soon turned up in grocery stores around the South and was the first Black-owned farm to supply food to the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The siblings enjoyed rapid success until a series of natural disasters forced them to take production offline and the USDA delayed their request to defer loan payments. Stewart lost the 80-acre tobacco farm she’d posted as collateral and developed a heart condition from the stress; her doctor, she recalls, “worried I was going to take my life.” Taylor had a nervous breakdown that landed him in the hospital.

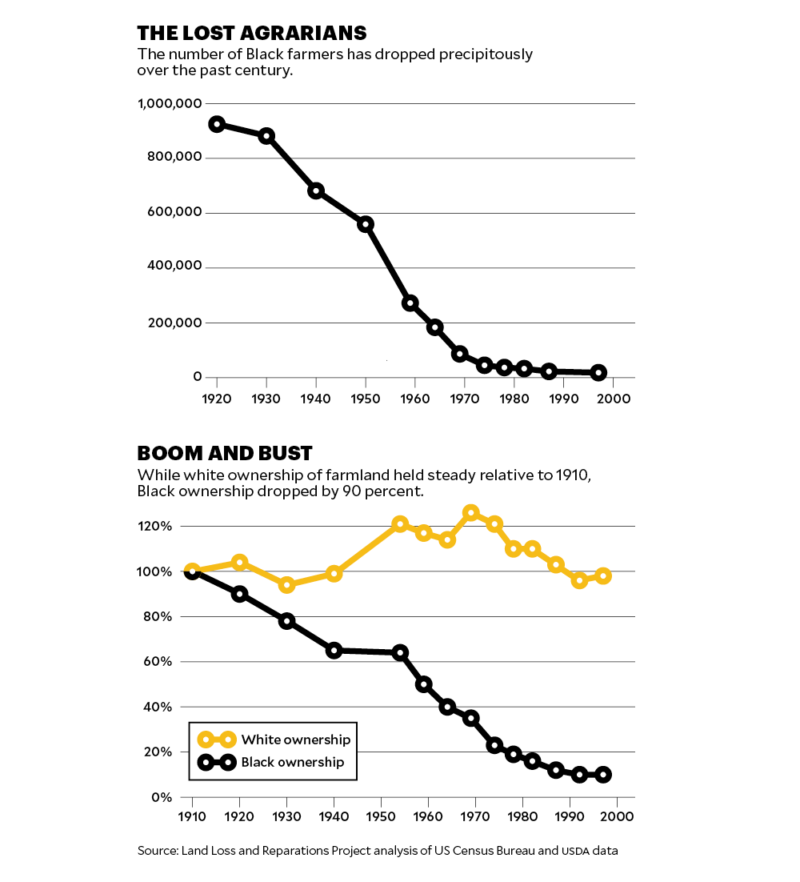

It’s easy to think of this as a one-off story of personal calamity. But what happened to Taylor and Stewart is distressingly common among Black farmers, who have lost more than 90 percent of their land since 1910—16 million acres, a landmass roughly the size of West Virginia—in part due to widespread discrimination by USDA bureaucrats who refused them loans, acreage allotments, and other forms of support that white farmers in similar situations easily obtained.

Black ownership of farmland peaked in the early 20th century. And while you might assume the New Deal, the civil rights movement, and President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs helped Black families build on that land base, “it was the opposite,” says Pete Daniel, a historian and the author of Dispossession: Discrimination Against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights. “A lot of the reason for that was in the Department of Agriculture and how its programs were racist. The people who carried them out were trying to get rid of Black farmers,” Daniel says. The people in charge at the USDA’s headquarters in Washington “never took action against any of the bureaucrats who were racist and abusive, so they were complicit with this behavior.”

In 1965, the agency’s first civil rights director was appointed to try to clean up its entrenched discrimination. President Richard Nixon later established an entire office dedicated to the task. But in the years since, the department’s civil rights office has been ineffective at best and actively biased at worst, according to our analysis of thousands of pages of documents and interviews with 29 current and former department employees. Far from safeguarding farmers’ and even its own employees’ rights, the civil rights office has instead often buried or ignored their complaints. Agency officials who attempt to change that pattern have found themselves sidelined. “Doing right” when it comes to USDA civil rights enforcement, one employee tells us, “is a lonely, lonely, lonely business.”

The Trump administration intensified the civil rights office’s dysfunction, putting officials in charge of the office and its legal counterpart who’d cut their teeth seeking to undo civil rights protections in other realms. Although President Joe Biden has voiced support for civil rights enforcement at the agency, USDA staff and food justice advocates for victims of discrimination say his plan just dusts off promises that were broken during the Obama years. “It’s just a gargantuan power structure that’s pretty unshakable,” Daniel says. “But that doesn’t mean we can’t try to fight.”

Renee Stewart and her brother, Valee Taylor, stand in the building that used to house Taylor Fish Farm.Image: Photography by Madeline Gray

With about 85,000 employees working across 17 subagencies, the USDA is one of the largest federal departments. It oversees the Forest Service and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (what used to be called food stamps), loans for rural businesses and infrastructure, farm credit, and even some low-income housing.

The modern USDA took shape under the New Deal, as Southern Democrats used their enormous influence to ensure that all those new federal programs wouldn’t challenge segregation. As documented in political scientist Ira Katznelson’s 2005 book, When Affirmative Action Was White, they made sure that federal resources would be distributed under “local control.” Through the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, which was designed to pay farmers to curtail production, the government established county committees that helped determine and distribute farm subsidies. Plantation owners and other Southern elites controlled these committees and the many other farm programs initiated by the New Deal—always ensuring that most of the money ended up in the hands of powerful white men. The USDA’s central role in this pattern of discrimination would earn it the nickname “The Last Plantation” among Black farmers.

By the mid-1960s, civil rights activists had trained their sights on this Jim Crow farm system, running Black candidates for spots on USDA county committees that distributed enormous amounts of farm aid. In 1965, the US Commission on Civil Rights released a scathing report that documented ongoing entrenched discriminatory practices throughout the USDA’s Southern offices. The same year, Agriculture Secretary Orville Freeman responded by appointing the department’s first civil rights director, William Seabron. It was mostly symbolic: Seabron drew up an aggressive reform plan, which included integrating the local committees, but department officials by and large ignored his recommendations.

Many of the USDA bureaucrats were under the sway of deep-seated Southern interests, personified by Rep. Jamie Whitten, a segregationist landowner from the Mississippi Delta who cultivated allies and spies within the department. As a powerful member of the House Agriculture Appropriations Subcommittee, he killed department reports on Black farmers and farmworkers and statistical agencies that studied poverty. When Congress debated expanding food stamps in Whitten’s deeply impoverished home state, he said if “hunger is not a problem, nigras won’t work.” He assured a Mississippi administrator in the county committee system that he could ignore integration orders from Washington and entered a passage in a congressional report arguing that Freeman couldn’t enforce civil rights laws. Lacking the appetite to challenge the lawmaker known as the “permanent secretary of agriculture,” Freeman told reporters that he had two bosses: “One is President Johnson. The other is Jamie Whitten.” With no mandate or power, the office would later descend into mismanagement and chaos.

Image: Mother Jones

President Nixon pushed for moderate civil rights reforms in part to drive a wedge between labor and civil rights groups. As part of that effort, he created the USDA Office of Civil Rights. But this merely gave an official name to a body with no real power. Only a few years later, when Earl Butz was secretary, 80 percent of its staff was moved to unrelated work—an overt signal of the administration’s abandonment of civil rights. This established a pattern at the department. As Daniel puts it, since its inception, the office has “been told not to do anything and has the personnel within it that can ensure that nothing will be done.”

This legacy of deliberate inaction persists. Local USDA offices originally established to defend white supremacy still garner hundreds of discrimination complaints against themselves every year, advocates and farmers say, and the department almost never resolves them in favor of the complainant or punishes employees for wrongdoing. The systemic attack on Black farmers is partly why 98 percent of commercial farms are now owned by white people, and the agency’s loan programs mostly enrich large, white-owned farms. The USDA even named its Washington headquarters after Whitten—in 1995. According to Lloyd Wright, who headed the civil rights office under President Bill Clinton, “It doesn’t matter who’s running the damn plantation because it doesn’t change very much.”

Wright at least tried to change it, supporting what would become the largest civil rights settlement in US history. It resulted from a landmark class-action lawsuit, Pigford v. Glickman, filed on behalf of Black farmers who experienced discrimination from department employees between 1981 and 1996, when the civil rights office had effectively stopped investigating discrimination complaints. For decades, wrote the judge, who ruled in their favor in 1999, “the Department of Agriculture and the county commissioners discriminated against African American farmers when they denied, delayed or otherwise frustrated the applications of those farmers for farm loans and other credit and benefit programs.” The $1 billion settlement, he continued, was “a first step of immeasurable value.”

Valee Taylor was one of more than 33,000 claimants in the ultimate settlement. In the early 1980s, he’d applied for a $325,000 Farm Service Agency (FSA) loan administered by the USDA. But the agency denied Taylor on the grounds that he had no farming experience, even though five generations of his family had been farmers, and he’d worked on the family farm in high school. Though they won the legal battle, individual farmers received little from Pigford; a typical payout was about $50,000, which neither relieved most plaintiffs’ debts nor helped them regain their land. And the case sparked substantial resentment among some conservatives, white neighbors, and local USDA staff who thought Black farmers had been paid off by the Democratic Party or given a backdoor form of reparations.

When the Obama administration settled with a new class of Pigford claimants in 2010, right-wing commentator Andrew Breitbart covered the case obsessively, describing the settlement as a Democratic “vote-buying scheme.” In March 2010, Breitbart published selectively edited video clips that made it seem like Shirley Sherrod, the head of the USDA’s Rural Development office in Georgia, had admitted to discriminating against a white farmer. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack immediately fired Sherrod. When the rest of the video emerged, making clear Sherrod had done no such thing, Vilsack offered her another post within the USDA which she declined. (She sued Breitbart for defamation and settled out of court.)

Pigford also highlighted internal divisions in the department. “We had a small group of people who supported Pigford and all of the class actions we settled,” agrees Joe Leonard, the USDA’s civil rights director under Obama, and “a large amount of people who did not.” In 2002, three years after the first Pigford settlement, Congress reorganized the civil rights office, renaming it the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights (OASCR, often pronounced “Oscar” within the division). But while Vilsack would say the case “helped close a painful chapter in our collective history,” the resentments linger. According to one former civil rights office employee, “The USDA employees who were around [during Pigford] still have the same anger that Black farmers got something they didn’t deserve.”

Taylor and Stewart’s grandparents Berea “Burrie” Corbett (center) and Nannie Corbett (right) at their family’s tobacco farm in Cedar Grove, North Carolina, in the 1930s.Image: Photograph courtesy Valee Taylor and Renee Stewart

Taylor and Stewart’s parents had met in 1952, when their father, Jerry, was attending North Carolina Agricultural and Tech State University, and their mother, Scnobia, was at school nearby. Jerry became one of the Army’s first postwar Black pilots. In 1968, he went to Vietnam and the rest of the family moved to Cedar Grove. Life in the 3,000-person town was a profound culture shock for Taylor and Stewart after a childhood spent in integrated military schools. Their mother became involved in local civil rights organizing, and together with their cousins, the siblings were at the forefront of Orange County’s long-delayed school integration. Their white neighbors burned crosses in their yard, shot at them when they collected mail, and hung their German shepherd from a tree.

One morning, when Taylor was 12, the school bus driver pulled over to allow Klansmen to drag him outside for refusing to sit where Black students were expected to sit. “They were looking for that uppity [n-word] that wouldn’t sit on the back of the bus,” Taylor recalled. “They were trying to kill me.” When the bus arrived at school, Taylor was suspended for fighting back. The next day, his mother made him return to school, and a caravan of Taylor and Stewart’s aunts and uncles followed the school bus, shotgun barrels sticking conspicuously out of their truck windows, in case the Klan was tempted to try again. The violence he endured as a child left Taylor diagnosed with PTSD later in life.

In 2007, after having worked for 20 years as a parole officer, Taylor was itching to return to his family’s roots. North Carolina was moving away from tobacco farming, and he and Stewart, then working as a pharmacist, wanted to build something lasting, a farm their children could own 50 years down the road. They applied for a series of FSA loans totaling $600,000 to get things off the ground.

Their idea was unique: raising tilapia in a sustainable, recirculating system they’d developed with two aquaculture experts at nearby North Carolina State University. “Tobacco was going out and we thought it would be a good transition,” Stewart says. “We thought it would flourish.” Taylor spent several months learning how to raise fish indoors and maintain the elaborate filtration and oxygenation systems they require.

Yet from their first meetings with the FSA, things seemed off. After two years and what seemed like interrogations from nearly every FSA loan officer in the state, Taylor and Stewart got their loan—but hardly on optimal terms. They were forbidden from applying as a limited liability company, which left them with significantly higher debts if their business failed. For collateral, they had to post Stewart’s house as well as the 80-acre farm she owned. When they went to Raleigh to sign paperwork, a white FSA employee asked Stewart whether she was using a marijuana farm as collateral, leaving her in tears. “I don’t know where it came from,” Stewart recalls, “except if he felt that if Black folk are making it, you’ve got to be doing something illegal.” After the farm was up and running and Taylor and Stewart established a network of grocery and live market buyers for their fish, one of their customers told them that their FSA loan officer had disclosed details to him about their debt, they said—leaving them at a competitive disadvantage, as the buyer subsequently timed all purchases to their installment dates.

Nevertheless, the business began to take off, attracting news coverage and gaining a large share of Whole Foods’ Southern and mid-Atlantic tilapia sales by 2014. North Carolina State University brought farmers from overseas to tour Taylor Fish Farm as a model they could copy back home. But disaster struck in 2014, when an ice storm hit Orange County, followed by a hurricane, knocking production offline for months. While insurance eventually covered the losses, it took a year for the payments to arrive. Meanwhile, their annual $100,000 FSA loan payment was coming due.

In October 2015, according to USDA documents pertaining to a later investigation, after months of requesting disaster assistance from the FSA, Taylor and Stewart emailed their loan officer at the time, saying they couldn’t make their February 2016 installment and asking to defer payment by one year. It shouldn’t have been hard. In response to the 1980s farm crisis, Congress passed legislation requiring the USDA to offer struggling farmers an opportunity to restructure their debt. But FSA fulfills this policy with little oversight, and in practice, Black farmers aren’t given the same accommodation white farmers receive. While Taylor and Stewart were hurting for cash, Taylor says, the FSA wrote off $1 million in debt for a white friend of his. The siblings’ loan officer even told them how one of his clients successfully postponed repayments by restructuring 16 times. Taylor asked the FSA for a reasonable disability accommodation for memory loss caused by his PTSD. He requested the loan officer communicate with him by email rather than by phone, copy Stewart on their correspondence, and meet in person for any necessary paperwork—something, Taylor says, the loan officer did not consistently do.

In early January 2016, the siblings met with the loan officer, who they say told them their application was complete. (Later, when asked about this by USDA investigators, the officer denied having said it.) Under FSA policy, loan officers are required to send applicants a 30-day notice if they’re missing any application materials. No such notice was ever sent, but in late January, the officer called Taylor to request more information. When Stewart quickly sent it, the officer said he couldn’t promise to review their application before their payment was due in February. The due date came and went, meaning that going forward, any restructuring would now include liens on all of Taylor and Stewart’s assets.

Over the next several months, the loan officer wrote the siblings roughly once a month, requesting more information—about their finances; a fish-processing outbuilding they were erecting; the grant supporting that expansion; forms that became outdated during the wait and now had to be filled out again; and how they’d managed to stay current on another loan if the farm had run at a loss.

Finally, in June, the officer declared their application complete. But now that their loan was over 90 days delinquent, the FSA would only restructure it if Taylor and Stewart provided additional collateral worth $850,000. The siblings refused the deal. They filed a complaint with OASCR, alleging that the FSA had intentionally delayed processing their loan restructuring, which constituted discrimination due to race, sex, disability, and their status as Pigford complainants—something Taylor and Stewart had made clear from their first communications.

That July, a bank loan they’d applied for was approved for $670,000—enough to get back on their feet and even expand. But according to Taylor and Stewart, the FSA said its loan had to take priority, effectively blocking the new loan. Simultaneously, Taylor was diagnosed with prostate cancer. His doctor told him his body couldn’t handle the stress of fighting both cancer and the FSA. So the siblings let it go. In 2019, Taylor Fish Farm closed for good. It seemed like the history of what had happened to so many other Black farmers had repeated itself. “They take minority farmers [who] put up everything they have,” Stewart says. “They set you up for failure, and then they take your property.”

Taylor and Stewart didn’t hear back from OASCR until May 2017, 11 months after they’d filed their complaint. After submitting more information to an investigator, they didn’t hear anything until September 2018, when they were emailed a short list of follow-up questions and given about a week to respond. They wouldn’t receive a verdict until September 2019, more than three years after they’d filed their complaint. In OASCR’s final decision, the agency’s adjudicator took the loan officer’s word on virtually every point and dismissed the majority of their complaint.

The entire process struck the siblings as absurd. According to an internal memo we obtained, at least one OASCR official thought so, too. In a 12-page document from November 2018, Queen Kavanaugh, a senior equal opportunity specialist at OASCR’s Center for Civil Rights Enforcement who wrote final agency decisions, identified numerous violations of USDA protocol in the Taylor Fish Farm case. She noted that OASCR’s investigator had contacted Taylor directly instead of his lawyer. While Taylor had made seven claims of discrimination—including the FSA refusing to accept his loan payments, reneging on promised debt relief due to natural disaster, and failing to accommodate his disability—OASCR deemed only one worthy of investigation. “What is a USDA employee supposed to do when there is a stark conflict between the USDA mission statement…and the way program discrimination complaints are processed?” Kavanaugh wrote in an email to an OASCR official accompanying the memo.

When we spoke, Kavanaugh confirmed she wrote the memo, with the hopes of showing higher-ups how cases were being mishandled. A Baltimore native, she had joined the USDA when she was 49, after an earlier career working in a personal injury law practice as well as a brief stint as a Baltimore police officer in 1973—part of the first class of female patrol officers in the city’s history. That experience, as well as childhood memories of attending a civil rights march with her grandmother, where a white woman spat in her face, had left her with the conviction that challenging authority was an obligation.

When she started at the USDA in 1998, Kavanaugh served as an agriculture complaints examiner, traveling state to state to investigate farmers’ claims. Informed by her experience conducting investigations, she was shocked by how the Washington office handled them. She says she watched OASCR managers artificially inflate the number of complaints coming in by accepting cases that should have been addressed at the local level so they could automatically dismiss them, creating the appearance of progress and garnering managers promotions and bonuses. Meanwhile, the process for investigating legitimate complaints was so shallow that it was nearly impossible for complainants to prevail.

In a statement, a USDA spokesperson disputed claims of data manipulation and assertions of discrimination at the agency, and said that OASCR processes all complaints of discrimination according to its regulations.

“Here’s how the investigations are done,” Kavanaugh explains. “I’m a farmer. I apply for a loan, never get it, get jerked around, so I file a complaint. I use the complaint form, but I don’t understand it. I put in information that I think will be helpful, and I think that when they get my complaint in Washington, I’ll have a chance to explain more fully what happened to me.” Instead, she says, when investigators get around to reviewing complaints, they typically send complainants written questionnaires, which may not cover pertinent information, but which, after complainants sign them, become their main testimony in the investigation. Those “affidavits,” Kavanaugh says, are then sent to the USDA employees accused of discrimination—employees who typically control the files documenting the case and can ensure it supports their version of events. Investigators, according to Kavanaugh, don’t do much more probing because it’s too time-consuming. When Kavanaugh did ask additional questions as an investigator, she says a supervisor chastised her, calling her reports late because she spent too much time “always being critical of what was going on in the state offices.” That is, Kavanaugh was digging for evidence of discrimination instead of moving the cases along.

“Nobody is checking the law or trying to come to an understanding to see if this [employee] is telling the truth,” she says. “Nobody is trying to understand what happened. So based on the way we do investigations, by sending out these questions, it’s guaranteed to be a finding of non-discrimination.” That might be a problem if OASCR actually saw its mission as determining whether discrimination occurred. “But the purpose of our job isn’t that,” Kavanaugh says. “It’s to shuffle complaints through in 30 days or less so the numbers go down.” (The USDA spokesperson stated that this characterization of the complaints process was “incorrect.”)

Kavanaugh’s description echoes a common complaint among OASCR employees we interviewed: Civil rights enforcement during the past few administrations boiled down to a fixation on numbers. During the Bush administration, OASCR made just one finding of discrimination among more than 14,000 USDA complaints from the public. Between 1999 and 2009, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released at least 10 reports chronicling the USDA’s failure to address complaints, as well as low morale within OASCR, which, witnesses told Congress, was rife with mismanagement and discrimination problems of its own.

When President Barack Obama took office, Vilsack vowed to overhaul the complaints process. The new ag secretary and his OASCR head, Joe Leonard, declared that “a new era for civil rights” had come to the agency. By the time he departed in 2017, Vilsack claimed success, citing record-low customer and employee complaints, including a 70 percent drop in complaints about FSA’s lending programs.

But interviews with 19 current and former OASCR employees, and a trove of USDA data, show that those claims were untethered from reality. One former high-level employee described his “high hopes” when Obama took office: “Finally, you know, maybe you had an administration that would come in and really clean up these civil rights issues—make it fair, do the right thing. And it was almost the opposite.” While Vilsack boasted that his department had cleared out the massive backlog of 14,000 complaints that had amassed during the Bush administration, in reality, almost all were closed without restitution for the complainants.

Former civil rights chief Lloyd Wright, who worked briefly under Vilsack before leaving in frustration, described OASCR as functioning like “a closing machine,” ferreting out “every little nick and corner they could find as a reason to close a complaint, or not accept them to begin with.” Rather than investigate and assess the substance of complaints, upper management disqualified them for technical reasons, like being turned in late or incomplete. In Vilsack and Leonard’s OASCR, numerous rank-and-file employees say that top managers became obsessed with reporting numbers that made the department look good. As one longtime employee remarked of how complainants’ cases were handled, “They’re not cattle, you know. They’re real people.”

Two former high-level OASCR officials say Leonard personally pressured them and other supervisors to fudge the numbers. “Let’s say if I gave him the numbers and there were 350 cases,” says a career civil service administrator who held a number of high-level appointed positions in federal government before working for Leonard, “he would get upset. He would say that’s not accurate. And he would go [to one of my colleagues] to say it was 100 cases.” That sort of pressure, another official says, meant OASCR’s statistics were manipulated at every stage of the complaint process. In an emailed statement, Leonard said claims that he or any of his staff altered the number of civil rights complaints are “an absolute falsehood.”

“After I refused to hide those numbers, I was blackballed,” the first administrator adds, echoing grievances made by a number of other OASCR employees who say they were sidelined for speaking out.

In its 2016 report to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, USDA staff acknowledged their records about complaint numbers were not reliable, writing, “USDA has struggled maintaining data integrity.”

Much of the problem, according to nearly every employee we interviewed—including Leonard—stems from the improper entanglement of the Office of General Counsel (OGC) with OASCR’s work. By definition, the OGC is the USDA’s legal defense arm, meant to protect the agency against lawsuits and complaints, including civil rights grievances. That puts its role in direct conflict with OASCR’s, and it’s why federal law mandates a firewall between the two divisions. But multiple employees we spoke with claim that the OGC has involved itself in adjudicating discrimination complaints since at least the late 2000s, when two GAO reports documented such line-crossing. Under the OGC’s pressure, says one OASCR employee, complaints are frequently weakened to the point that complainants don’t stand a chance of winning. “They want people to take a complaint and dilute it, so if it has six issues, reduce it to two,” one of our sources says. If the employee finds discrimination, “They’ll tell you, ‘This is not discrimination. Go and rewrite it.’”

Other employees say managers send complaints to the OGC to get them thrown out. “Even if someone has a compelling case,” one says, “it goes to OGC and OGC figures out a way to draft some language up that basically denies or closes out the complaint.” Even Leonard acknowledged this, telling us the OGC makes “all the decisions.” He adds, “There was supposed to be a separation between OGC and civil rights, but nobody’s ever told them there was one.” (A spokesperson for the USDA stated that the two agencies maintain a firewall, and that the OGC does not encroach upon OASCR’s processing of complaints.)

The problems extend to the employee civil rights complaint process as well—from the Forest Service to Rural Development to OASCR headquarters itself. A 2015 investigation by the federal Office of Special Counsel found “OASCR has an unusually high number of complaints filed against its own leadership” and “almost half of these complaints were not acted on in a timely manner.”

When one OASCR employee who says he was sexually harassed by a high-level manager went to submit a complaint, he tells us, the woman he filed it with said he was making a mistake. “She was just like, ‘Yeah, baby, I wouldn’t do that. I would just leave that alone.’” He filed it anyway and lost his job within months. As Lesa Donnelly, vice president of the advocacy organization USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, testified in 2016 to a House oversight committee conducting a hearing on sexual harassment within the Forest Service, “I question how the Office of Civil Rights can address systemic and institutional issues of discrimination when they are not capable of managing their internal personnel problems and violations of civil rights.”

During the Obama years, Queen Kavanaugh joined several of her OASCR colleagues in deciding they “were not going to play the numbers game” of inflating and dismissing complaint counts to foster the illusion of progress. “When you see cases where people are being hurt, but the people whose job it is to do something about it won’t, that’s something I just can’t shut up about,” Kavanaugh says. “Especially when a lot of people being hurt were in the struggle to get the Civil Rights Act in the first place.”

She tried to alert her supervisors to problems, at first assuming they simply lacked experience in how investigations should be done. She made a PowerPoint presentation for one supervisor, laying out the legal implications of two federal appeals court decisions involving complaints that originally went through OASCR. Both times, Kavanaugh says, “the federal court of appeals examined our procedures and made a determination that what we have is not a proper administrative procedure, but some sort of executive fiat.” But when she pointed this out to more senior staff, she says, “this was all ignored.”

So she went higher. Between 2015 and 2019, she reached out to numerous federal authorities. She emailed information to the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, citing a Harvard study that found “a general sense of hopelessness for change” among OASCR employees, and distrust of OASCR by other USDA agencies. She helped draft a letter for the federal employees’ union, offering a side-by-side comparison of claims Joe Leonard had made about civil rights accomplishments and her reasons why they weren’t true. She wrote the Senate agriculture committee, requesting that they condition their recommendation about any new USDA secretary on the nominee’s willingness to address OASCR mismanagement. She wrote both Vilsack and his successor, Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue, describing how investigations were intentionally stacked against complainants.

And when she wrote her memo on Taylor and Stewart’s case, she didn’t think she could change the outcome. Instead, she hoped the record might work its way up the departmental ranks, since she’d lost all faith that OASCR could reform itself. It had become clear, she says, “that they don’t really want to investigate these complaints at all.”

Instead of any intervention, she says the case was taken away from her. Ever since she’d begun speaking out, she’d been sidelined, reassigned to busywork while her old responsibilities were distributed to contractors. In 2019, she was put on disciplinary probation after emailing colleagues a sharply worded critique of an outgoing manager, who she said had distorted program complaint figures and blackballed OASCR employees who refused to play along. In an official letter of reprimand about this incident, Kavanaugh’s direct supervisor said she’d humiliated OASCR and distracted from “mission critical responsibilities,” and if she did so again, she could be fired. (A USDA spokesperson declined to comment.)

In January 2020, Kavanaugh retired early, convinced nothing she did would change the civil rights office she once believed in. “I was so fed up,” she says. “It was obvious to me that there was nothing I could do.”

The building that once housed Taylor Fish Farm now sits empty.Image: Photography by Madeline Gray

Under president Donald Trump, Shawn McGruder, who’d worked for five years in the OGC and reached a top management position, was named executive director of OASCR’s civil rights enforcement, solidifying the convergence of the two offices. Under her watch, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission rejected OASCR decisions on employee discrimination complaints by the dozens. By 2018, the USDA’s reversal rate was over 50 percent higher than the average across all federal agencies. And although USDA employees filed 522 complaints in 2018, OASCR’s office of adjudication made only one finding of discrimination.

The same year, a new problem emerged. An email account established in 2015 to receive incoming program complaints had been left unmonitored by OASCR staff, meaning people who claimed they were discriminated against in applying for things like food stamps were sending their complaints into a void. It also meant many people lost their legal rights to press a civil rights grievance, one employee explains, because their cases weren’t processed in time. McGruder would tell staff that a “glitch” had caused the office to lose or fail to respond to some 20,000 emails, two employees tell us.

But we unearthed documents that appear to indicate that by the end of the 2017 fiscal year, the email account had actually received about 63,000 emails, only 22,000 of which had been opened. When staff became aware of the problem during the next fiscal year, 111,000 emails were opened in what seemed a frantic effort to catch up.

“I am an elderly disabled woman,” read one email sent to the account. “My snap benefit is my only source of providing food and nutrition.” “I just need an appointment asap,” read another, from a complainant who’d recently lost a foot to gangrene. (McGruder wrote in an email that the mailbox was established before her tenure, and that, except for during a government shutdown, “at no time during my tenure did any mail go unattended.”)

The continued dysfunction in OASCR has taken a toll on its staff. “Many of us loved what we did—we loved our work,” says one high-level employee. But “when you try to do the right—when you do the right thing and then you are trapped, discriminated [against]—it’s like a career death walk.” A 2019 survey of federal employees by the Partnership for Public Service ranked OASCR the third-worst federal agency to work at out of 420. The only two agencies to rank worse had recently seen mass firings and deep budget cuts.

In the early days of 2020, some OASCR employees and outside civil rights advocates saw signs of hope in the Democratic presidential primary field. Sen. Elizabeth Warren released a wide-ranging plan to address discrimination at the USDA that included a vow to “radically restructure the office that handles civil rights” by creating an independent oversight board and a civil rights ombudsman, and ordering the Department of Justice to investigate the civil rights office. The plan also detailed reforms for the complaint process and ending OGC interference. (The Warren campaign had solicited input on its plan from two of this article’s authors, Nathan Rosenberg and Bryce Stucki, who are both analysts for the Land Loss and Reparations Project.)

The plan Biden floated, by contrast, downplayed past problems and heralded the “historic progress” on civil rights and inequality accomplished by the “Obama-Biden” administration. The plan didn’t include policies to address specific wrongs perpetrated against Black farmers, but rather offered general policies to help nonwhite farmers. And then Biden announced he had selected Vilsack for a second term as secretary of agriculture.

Black farmers and civil rights organizations were outraged. Lawrence Lucas, president emeritus of the USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, told the nonprofit food news website the Counter that Vilsack “has inflicted enough suffering…This brings tears to my eyes.” In a letter to Biden the same week, former USDA Civil Rights Director Lloyd Wright wrote: “Mr. Vilsack had 8 years to address Black farmer and Black employee issues and he failed. It is very clear who understands and supports Black farmers in this country and it is not Mr. Vilsack.” Michael Stovall, a Black farmer and Pigford claimant, told Politico, “It’s very disappointing they even want to consider him coming back after what he has done to limited resource farmers and what he continues to do to destroy lives.”

Vilsack has declared he will “continue the important work of rooting out inequities and systemic racism in the systems we govern and the programs we lead.” A backgrounder that the Biden transition team sent to reporters repeated the claim that Vilsack had reduced a backlog of 14,000 complaints from the Bush years, and that his department received the lowest number of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaints on record, even though the USDA’s own data showed an increase compared with the early 1990s.

The agricultural industry and organizations representing large-scale farmers, such as the American Farm Bureau Federation, were largely pleased with Vilsack’s nomination. His supporters have defended his civil rights record in several newspaper interviews, pointing to, among other things, his creation of the department’s Advisory Committee on Minority Farmers. Some also claimed he was undergoing what amounted to a political awakening. “Mr. Vilsack is changing along with the conversation,” wrote Art Cullen in a New York Times op-ed.

But others see little reason to believe Vilsack has changed. “I don’t see why all of a sudden he’s going to fall in love with civil rights,” says Kavanaugh. While Vilsack has promised to expand outreach to Black farmers and address “inherent legacy barriers”—promises he also made during the Obama administration—he hasn’t said anything specifically about the USDA’s civil rights complaint process. And unless the civil rights office is completely overhauled, advocates say, the discrimination will continue. “Nothing is going to change,” says Kavanaugh, “until you get an administration that will wipe out this existing way [of handling complaints] and do something different.”

What Lucas and others want is clear: an end to blatant and widespread discrimination; accountability for the malfeasance that has harmed thousands of farmers, employees, and customers; and financial and legal restitution for those who’ve been harmed. Along those lines, the stimulus bill that passed in March included $4 billion in debt relief for farmers of color. A recent Senate bill co-sponsored by Warren, Cory Booker, and Kirsten Gillibrand would create an independent review board to provide oversight of the civil rights process at the USDA.

For Taylor and Stewart, who’d once hoped to grow old on their farm and pass it on to their children, what’s at stake is the future of families like theirs. When Taylor speaks to young Black farmers—“all bright-eyed and ready to conquer the world, like I was”—he finds himself dismayed by the obstacles they’ll face. “You know in the back of your mind, unless we straighten out the USDA, they’re not going to have a chance,” he says. “The USDA just seems like a machine that eats up Black farmland.”

“It’s a wonder we were able to succeed as long as we did,” adds Stewart. “I never would do it again.”