This article contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault.

On the night of June 5, 2017, a soldier stationed at Camp Lemonnier, a sprawling U.S. military base in the sun-bleached African nation of Djibouti, started her first shift with Alpha Company. She wasn’t happy about the new assignment. Transferring to Alpha Company meant joining a team without anyone she knew. There was also talk of sexual harassment within the unit.

Around midnight, she reported for duty at a guard post, where she found herself alone with a male noncommissioned officer who outranked her. He told her that he had been watching her for almost nine months, ever since a pre-deployment ceremony at which he decided that he wanted to “eat her pussy.”

The harassment made her uncomfortable, but she didn’t protest, because she was afraid that the soldier would become violent, she later told military investigators. When it was time for her to rotate to the next post, around midnight, he said she should stay, then stood up and told her to “suck his dick.” She told investigators that he “was not taking no for an answer.” He warned her that if she reported him, no one would believe her, because she had less military experience. Fearing for her safety, she began masturbating his penis before he forced it into her mouth.

The incident is one of 158 cases of sexual crimes — including rape, sexual assault, and abusive sexual contact — involving U.S. military personnel in Africa that were reported over the past decade, according to criminal investigation records from the Army, Navy, and Air Force that The Intercept and Type Investigations obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

While many of the files are heavily redacted, making it impossible to identify the military personnel involved, they nonetheless shine a light on the operations of U.S. Africa Command, or AFRICOM, whose commanders and troops have been embroiled in a long series of scandals. Even more striking is the fact that the number of incidents described in the files are more than double the Pentagon’s official sexual assault figures for the African continent, highlighting the degree to which the military has failed to properly track cases of sexual offenses, thereby masking the overall severity of the problem.

The Pentagon’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office, or SAPRO, compiles annual reports to Congress that are supposed to include all reported cases of sexual assault involving U.S. military personnel. Between 2010 and 2020, the year of the most recent report, the Pentagon lists just 73 cases of sexual assault in the AFRICOM area of operations. Yet the files obtained by The Intercept and Type Investigations show that military criminal investigators logged at least 158 allegations of sexual offenses in the AFRICOM area of operations during that same period.

The case files reveal that these charges of sexual misconduct involving U.S. military personnel occurred in at least 22 countries in Africa — including 13 nations that do not appear in the annual Pentagon reports. Some of the allegations accuse members of the military; others recount attacks on U.S. personnel by civilians on or near U.S. outposts.

“Those numbers have made me ill,” said Erin Kirk-Cuomo, who served as a combat photographer in the Marine Corps and founded the nonprofit advocacy group Not In My Marine Corps to highlight the issues of sexual assault and harassment. “And I would imagine there are at least five times that number of assaults — just from what we know about unreported sexual assaults in general.”

AFRICOM is not unique. The problem of sexual misconduct in the military is chronic and widespread, with overseas deployments posing particular dangers. One study found that women with “combat-like experiences” in Afghanistan and Iraq had significantly greater odds of reporting sexual harassment or both sexual harassment and sexual assault. The Pentagon estimates that roughly 20,500 service members experience sexual assault each year, according to the latest Pentagon survey, but only 6,290 official allegations of sexual assault were made in 2020, according to the most recent SAPRO report. This year, the Government Accountability Office also found that the Pentagon had failed to document up to 97 percent of allegations of sexual assault of its civilian employees.

U.S. Airmen from the 449th Air Expeditionary Group load pallets of medical and humanitarian aid supplies, to be delivered to the Somali people, onto a U.S. C-130J Super Hercules bound for Somalia at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti Tuesday, Oct. 17, 2017.Image: Staff Sgt. Gustavo Castillo/U.S. Air Force via AP

The Department of Defense notes that survivors of sexual assault are often reluctant to come forward for a variety of reasons, including a desire to move on, maintain privacy, and avoid feelings of shame. Yet troops say that even when they do speak out, they often face a military culture and command structure that doesn’t take their allegations seriously and a military justice system that provides little accountability. Only a small percentage of cases are ever prosecuted, and they rarely — about 0.9 percent of the time, according to 2020 statistics — result in convictions for sexual offenses.

Most of the 158 reports identified in the AFRICOM files represent cases in which a member of the armed forces, or someone assaulted by them, wanted to seek justice through the military system. The fact that many of these reports may not be included in the Pentagon’s official records highlights how the military has failed to properly track sexual assault cases and take appropriate action to address the problem.

“I’m not surprised at all,” said retired Col. Don Christensen, a former chief prosecutor for the Air Force who is now the president of Protect Our Defenders, an organization dedicated to combating sexual assault in the military. “Their tracking process is very flawed. You see incomplete data, cases that aren’t tracked. You have missing information and reports that don’t seem to add up.”

A Pentagon spokesperson, Maj. César Santiago, said the Defense Department collects data on sexual assault to inform “policy, program development, and oversight actions” around the issue. “Each year, the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office aggregates data on reports of sexual assault, analyzes the results, and presents them in the Department’s Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military,” Santiago said in an email.

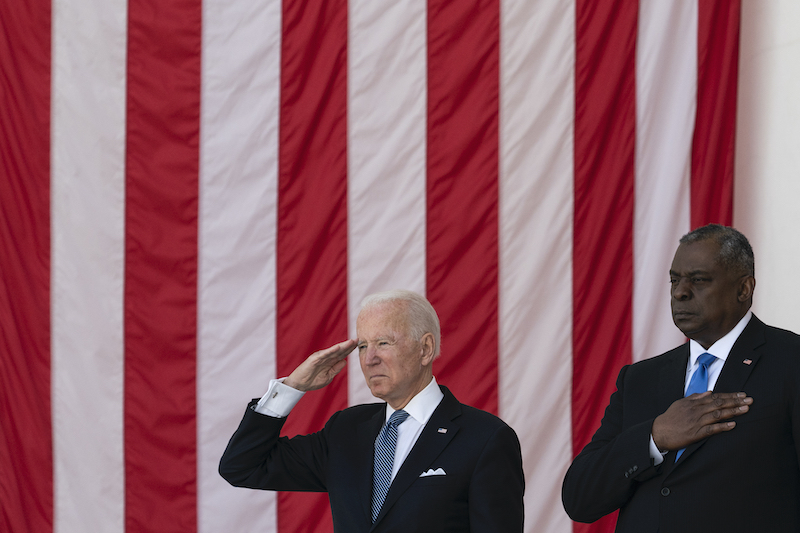

President Joe Biden salutes as Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin places his hand over heart during the playing of "Taps," during the National Memorial Day Observance at the Memorial Amphitheater in Arlington National Cemetery, Monday, May 31, 2021, in Arlington, Va.Image: Alex Brandon/AP Photo

The findings by The Intercept and Type Investigations come as the Biden administration makes combating sexual assault in the military a major policy goal. In January, as his first directive in office, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin issued a memorandum calling on senior Pentagon leaders and top generals to “battle enemies within the ranks” and wipe out the “scourge of sexual assault.”

Currently, commanders decide whether to charge a suspect with a sexual crime and whether a case should result in a general court-martial. Critics note that the system is rife with conflicts of interest. The situation is akin to a corporate executive deciding whether a case involving the sexual assault of one employee by another should go to trial. The military’s mostly male senior officers — who generally lack formal legal training — often doubt survivors, side with the accused, and may pressure survivors not to bring formal charges. There are just a tiny number of court-martial convictions of sex crimes.

On July 2, the Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault, established by Austin at President Joe Biden’s direction, recommended taking cases outside the chain of command, a change military leaders have long resisted. The commission recommended that independent judge advocates, reporting to a civilian-led Office of the Special Victim Prosecutor, should decide whether to charge an alleged perpetrator of sexual assault and whether that charge should result in a court-martial.

Both Biden and Austin have backed the proposal.

“I strongly support Secretary Austin’s announcement that he is accepting the core recommendations put forward by the Independent Review Commission on Military Sexual Assault (IRC), including removing the investigation and prosecution of sexual assault from the chain of command and creating highly specialized units to handle these cases and related crimes,” Biden said in a statement last week. “For as long as we have abhorred this scourge, the statistics and the stories have grown worse. We need concrete actions that fundamentally change the way we handle military sexual assault.”

It will be up to Congress to amend the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, a leading voice on the issue, also has bipartisan support for a bill that would take prosecution decisions out of the chain of command for major crimes, including rape and sexual assault.

Austin has made the collection of data a centerpiece of his efforts. His January memo directed military leaders to undertake a “frank, data-driven assessment” of sexual assault and harassment prevention programs. “A primary focus should be on how you are conducting oversight to ensure programs and policies are being executed on the ground,” Austin wrote. “Please ensure this assessment includes relevant data over the past decade, victim support efforts, and advocacy.”

A March 2020 report by a military advisory committee lamented, however, the “difficulty in obtaining, uniform, accurate, and complete information on sexual offense cases across the military.” This may help explain the discrepancy between the Pentagon’s annual figures and the AFRICOM files obtained by The Intercept and Type Investigations, a situation that has been advantageous to the military overall.

“They know that transparency and accuracy make them look worse,” Christensen said. “Often people give up and quit looking for this information, so it’s a win-win for them.”

The night after the alleged assault at the guard post in Djibouti, the female soldier said the same man attempted to assault her again. According to the case file, he tried to kiss her, then said that he wanted a relationship with her and that he would “shower her with gifts.”

After that, the female soldier filed an official complaint, which led to a military protective order prohibiting the man from contacting or communicating with her. Army investigative documents note that an officer believed there was probable cause that a sexual assault had occurred, and the case was referred to a commander to consider disciplinary or administrative action. It’s unclear whether any further action was taken in the case. Because the names of the troops involved are redacted in the case file and the SAPRO reports contain few details, it’s also unclear whether this case is one of the 73 allegations of sexual assault included in the Defense Department’s annual figures.

But the prevalence of these cases at AFRICOM highlights the degree to which military leaders have created a culture in which indiscipline and criminal behavior have been allowed to flourish at the command.

The command’s first chief, Gen. William “Kip” Ward, was investigated for spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on lavish travel and was demoted in 2012 after the Pentagon’s inspector general found that he had engaged in “multiple forms of misconduct,” including misuse of his position and wasting government funds.

In 2013, Maj. Gen. Ralph Baker, the commander of a counterterrorism force in the Horn of Africa, was removed from his job on charges of sexual misconduct. Baker had “forced his hand between [an AFRICOM senior policy adviser’s] legs and attempted to touch her vagina against her will,” according to a criminal investigation file obtained via the Freedom of Information Act. (Demoted to the rank of brigadier general, Baker was allowed to quietly retire.)

Maj. Gen. Joseph Harrington, the commander of U.S. Army Africa, was sacked and stripped of a star after he exchanged a large number of Facebook messages — 1,158 of them between February 12, 2017, and June 3, 2017 — with the spouse of an enlisted soldier. Air Force Lt. Col. Denis Paquette, the commander of a secret U.S. drone base in Tunisia, was dismissed from military service after carrying on a relationship with an airman and impeding the investigation that resulted. Troops stationed at Paquette’s drone base had gained a reputation for heavy drinking and hard partying.

Failures in military leadership in Africa have had fatal consequences. After four U.S. soldiers were killed in a 2017 ambush in Niger, a Pentagon investigation called attention to “a general lack of situational awareness and command oversight at every echelon.”

With little outside oversight, Camp Lemonnier has been the location of a high percentage of alleged sexual assaults of U.S. military personnel on the continent. A former French Foreign Legion outpost that has expanded from 88 acres to nearly 600 acres, Camp Lemonnier serves as a key hub for American counterterrorism operations in Yemen and Somalia. It is the largest U.S. base on the continent, hosting about 5,000 U.S. and allied personnel.

Alleged crimes at Camp Lemonnier, according to the AFRICOM files, include the following:

- In 2013, an investigation by Navy criminal investigators “revealed allegations of a history of sexually inappropriate comments and behavior” by an Air Force staff sergeant who harassed and touched female subordinates, including an instance in which he unzipped the blouse and forcibly spread the legs of a subordinate while she was on duty at a guard shack.

- In March 2015, a soldier allegedly plied a 20-year-old specialist with more than the allowed two alcoholic drinks, followed her back to her quarters, and sexually assaulted her. For weeks, the soldier continued to harass the specialist, walking into her quarters uninvited as well as kissing and touching her. She said she went along with it for fear of upsetting their professional relationship but eventually reported the incident. The final report by Army investigators notes that the allegations “could not be substantiated or refuted,” and the case was closed.

- In August 2015, a Navy chief yeoman reported that she was “hit, bit, and choked” as well as sexually assaulted by a U.S. Army staff sergeant.

- In April 2016, a specialist with the Army’s 2nd Battalion, 124th Infantry said that while sitting outside her quarters to use the Wi-Fi, another soldier began chatting her up and invited her to his room. When she declined, the soldier grabbed her hand and began pulling her away, eventually lifting her up and carrying her to his quarters. There, he proceeded to kiss her and grope her and tried to pull down her pants. She was able to escape when the perpetrator’s roommate walked in. The perpetrator then walked back to the specialist’s quarters and tried to kiss her again, then took her hand and attempted to place it on his penis, according to criminal investigative files.

- In June 2017, a Navy Exchange massage therapist said that a master-at-arms third class demanded “extra services” from her. She refused to perform any sexual acts and reported him. During the investigation, another massage therapist, a civilian, said the same man had groped her during a massage and also asked for “extra services.” After the massage therapists declined to provide further information, Navy investigators closed the case.

All of these incidents, whether the alleged victim was a civilian or a member of the military, are supposed to be included in the Pentagon’s Defense Sexual Assault Incident Database and listed in the annual SAPRO reports to Congress. But it’s not clear whether they are. The annual reports do not tell the whole story.

According to the SAPRO accounting over the last decade, sexual assaults involving U.S. military personnel were reported in nine African countries: Djibouti, Ghana, Kenya, the Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. John Manley, an AFRICOM spokesperson, touted the “wealth of data” in the SAPRO reports, which he said represented “all [Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention program] reporting throughout DoD.”

But the AFRICOM files obtained by The Intercept and Type Investigations include cases not just from those nine nations, but also from 13 others: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Ethiopia, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Morocco, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, and South Sudan. Those 13 countries do not appear anywhere in the annual reports.

“Overseas, it’s like the Wild West,” said Kirk-Cuomo. “In these deployed situations, there’s no oversight, and people feel like they can get away with it. There is no tracking. There is basically zero data on sexual assaults coming out of any of these places.”

Image: Vicky Leta/The Intercept

The redacted information in the investigative files makes it difficult to match the 73 cases in the Pentagon’s annual SAPRO reports with the 158 cases in the AFRICOM files. Whether some cases that occurred in Africa are logged elsewhere in SAPRO data is unclear because AFRICOM doesn’t track sexual assaults and the Pentagon declined to provide raw data or clarify the discrepancies. More than two years after The Intercept and Type Investigations first requested an interview with a representative from SAPRO, Santiago, the Pentagon spokesperson, replied, “Unfortunately, we do not have anyone available.”

One case that was omitted from the official Pentagon filings was an alleged assault of a soldier in Senegal.

On February 13, 2015, the soldier, who was supporting the U.S. response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, left a dinner with co-workers to return to her hotel in Senegal’s capital, Dakar. While walking past a group of young men, she reported that one of them grabbed her and slammed her into an alley wall. Another pulled down her pants. The men “were laughing and appeared to be joking as they were groping her and digitally penetrating her,” according to the file. The woman believed she was gang raped as well, although she had difficulty recalling details of the latter part of the assault.

The AFRICOM files include a copy of an Army criminal investigation report detailing the allegations. But Senegal is not mentioned in any of the Pentagon’s annual reports on sexual assault from 2010 to 2020.

“U.S. Africa Command has no record of these allegations,” said AFRICOM spokesperson Manley.

The AFRICOM files highlight the ways in which the military can actively discourage survivors of sexual assault from coming forward with their allegations.

Survivors of sexual assault said they felt reluctant or afraid to aid investigations, pressured to change their accounts, and constrained by their chain of command, according to the AFRICOM files. Some thought that they would not be believed and doubted that reporting an assault would lead to a positive outcome. Others were ignored, laughed off, suspected of exaggerating, or accused by leadership of lying about the abuse.

“Women are regularly treated like they’re the problem,” said Amy Braley Franck, who served as the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention program manager for U.S. Army Africa from 2015 to 2018. “They aren’t cared for, because the system doesn’t operate properly. And there’s no oversight.”

Members of the military who want to report a sexual assault say the system for doing so is difficult to navigate, even at the largest and best-resourced U.S. base in Africa. “In Djibouti, the Navy SHARP office is supposed to have a full-time staff member on the camp — which sometimes they do, but sometimes they don’t,” said Braley Franck. “Several times, I called their hotline number to get somebody to take care of a service member — because that was their responsibility — and nobody answered their phone.”

A spokesperson at Camp Lemonnier did not respond to repeated requests for comment about the allegation.

For instance, a soldier who reported being sexually assaulted while deployed in Africa, and who spoke to The Intercept and Type Investigations on the condition of anonymity, said she was unaware of even how to locate SHARP personnel or military criminal investigators on her base.

“Everyone thinks it’s just so easy to go talk to a SHARP representative or CID, but it’s not,” the soldier said.

The soldier highlighted another issue that has plagued the military: the failure of military leaders to take sexual assault seriously.

After she reported being assaulted, she said her superiors disregarded her allegations — although Army investigators later corroborated her claims. And it wasn’t her first such experience. Referring to a prior assault, she said she was frustrated by the process of seeking justice. “I learned that in the end nothing really happened, and I was told the defense would be able to change the story,” she said. The experiences left her embittered toward her superiors and skeptical of the military justice system.

“So many bad things happened when I did do the right thing, so I’m worried about what would happen if I did it again,” she said. “Leadership is not taking any accountability. If your soldiers are abusive, are acting like perverts, you need to put a stop to it. But leadership looks at it like, ‘Not my business. Not my problem.’”

The soldier was assaulted at Camp Lemonnier along with an Army specialist. The specialist, whose name is being withheld by The Intercept and Type Investigations, told Army criminal investigators that a delivery person from a local hardware vendor assaulted them as they were unloading supplies in April 2014 — grabbing them, grinding on them, kissing them, and licking their necks. They repeatedly shoved him away and shouted “No!”

“He was a creep and felt us up,” the specialist said.

But when the women reported the incident to their platoon sergeant, he brushed them off.

“Our sergeant’s response was, ‘I don’t give a fuck, write your congressman,’” the specialist told investigators.

The specialist said their commanding officer later joked that the locals liked “to play grab-ass with my soldiers.”

The soldier corroborated the specialist’s account in contemporaneous testimony to criminal investigators and in recent interviews with The Intercept and Type Investigations. It is unclear whether their case is included in the Pentagon’s annual figures. But years later, the specialist is still angry about the response from her commanding officer. “It really pissed me off,” she said. “At first, I couldn’t believe that it was just written off. But it happens all the time.”

The specialist was never the same after her report of the assault was shrugged off, according to the soldier who was assaulted alongside her. She went from a model soldier to one who didn’t care.

When she redeployed to Fort Polk, Louisiana, later in 2014, the specialist started smoking marijuana, even though she knew she might fail a drug test. When she did fail, she didn’t mount a defense, accepting a less-than-honorable discharge to expedite her departure from the Army.

Hers is a common story. A 2016 Human Rights Watch investigation found significant evidence of less-than-honorable or “bad” discharges being meted out to military personnel who reported sexual assault. And a Rand study released in February found that sexual assault doubled the odds that a service member would separate from the military in the ensuing 28 months. The research also showed that service members who said they were sexually harassed were 1.7 times more likely to leave the military over the same time span.

“The services are losing at least 16,000 manpower years prematurely subsequent to sexual assault and sexual harassment in a single year,” the Rand researchers wrote. “Furthermore, members who separate from service because of sexual assault or sexual harassment are likely forgoing considerable compensation relative to continuing their service; indeed, some victims likely give up hundreds of thousands of dollars in lifetime earnings.”

When a Navy criminal investigator asked the specialist what the worst part about the assault by the delivery person was, she didn’t mention the details of the crime itself. Instead, she said, the worst part was “knowing your leadership did not care.”

This betrayal was the hardest lesson of her military career.

“You think it’s enemies — people overseas — that you’ll need to fight,” she told The Intercept and Type Investigations. “You realize later that you don’t only have to fight enemies overseas, but also the people around you.”

If you have information about sexual assault in the U.S. military, email Nick Turse via nickturseTI@protonmail.com.

Research assistance provided by Darya Marchenkova.