More than four years have passed since Aaron Gach, a sculptor and installation artist, was detained at San Francisco International Airport. He was interrogated by U.S. border agents, and his cellphone was searched. He still doesn’t know why. “It has absolutely had a chilling effect on myself and my art practice,” he said. “They wouldn’t tell me why I was stopped or why I was detained.”

Gach is one of tens of thousands of Americans caught up in an effort by the Department of Homeland Security to collect personal information about travelers at land borders and airports. To further this goal, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the DHS agency responsible for policing America’s borders, relies on secretive units called Tactical Terrorism Response Teams, documents from an ongoing Freedom of Information Act lawsuit reveal.

A CBP spokesperson told The Intercept and Type Investigations that the teams, which are trained to conduct counterterrorism interrogations, currently operate at 79 ports of entry and in all 20 of the Border Patrol sectors nationwide. The units consist of CBP officers and Border Patrol agents who work closely with CBP’s National Targeting Center, which gathers and vets intelligence. Since its inception in 2015, the TTRT program has expanded its scope beyond counterterrorism, the spokesperson added, to include other areas such as “counterintelligence, transnational organized crime as well as biological threats.”

Between 2017 and 2019, the documents show, the units detained and interrogated more than 600,000 travelers — about a third of them U.S. citizens. Of those detained, more than 8,000 foreign visitors with legal travel documents were denied entry to the United States. A handful of U.S. citizens were also prevented from entering the country, which civil liberties advocates say violated their rights. Lower court and Supreme Court rulings affirm the constitutional right of U.S. citizens to freedom of movement and the ability to enter and leave the country.

Very little is known about how the secretive units operate, and CBP declined to respond to detailed questions for this story. The more than 1,000 pages — which include emails, training materials, and travelers’ complaints, most of them heavily redacted — offer a broader picture of how the program works as well as the type of information that CBP collects from travelers. The documents were released to the American Civil Liberties Union and the legal advocacy organization Creating Law Enforcement Accountability and Responsibility, or CLEAR, last year as part of a FOIA lawsuit that sought information on how the teams operated and whether constitutional and privacy protections were being violated.

Among the pages are several complaints sent to CBP by U.S. citizens, including Aaron Gach, who only discovered that TTRT agents were responsible for his detention after The Intercept and Type Investigations showed him the documents. “This at least gives some validation to my feeling at the time that my stop felt targeted and not random at all,” Gach said.

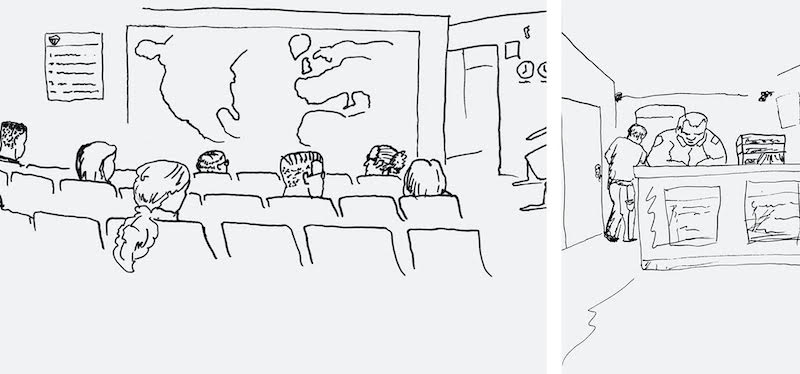

Two sketches Gach made while waiting to be questioned by TTRT agents at San Francisco International Airport in February 2017.Image: Aaron Gach

A Fishing Expedition

Gach was traveling home from showing his work at an art show in Belgium in February 2017 when he was stopped in the San Francisco airport. As Gach tells it, after waiting in a secondary holding area, two agents led him down a “dark, narrow, and grimy corridor” and seated him at a desk in a corner with a surveillance camera on the wall behind him.

The two officers, who said they were from CBP, questioned him about his art practice, how often he traveled for work, the show he had attended in Brussels, and who he had associated with there, including their phone numbers and email addresses.

As the interrogation continued, Gach said, he began questioning the two agents about his rights as a U.S. citizen, especially after they told him that he could not leave until they had searched his cellphone. “Do I have a choice in the matter?” he asked.

“Of course, you have a choice, but we can also be dicks and just take your phone as part of our investigations if we see fit,” one of the agents said, according to Gach. “Your phone and its contents are part of your personal effects, which are subject to examination when crossing any border into the U.S.”

Throughout the interrogation the two agents kept their tone jovial, which Gach said he found even more unsettling. If he did not unlock his phone for a search, according to Gach, the agents said they would confiscate his computer, hard drives, and other personal effects. “As a professor and as an artist, most of my work happens on my computer and on my hard drives,” he said. “I never consented to the search, but I did give them my cellphone.”

The reason for Gach’s detention is redacted in the documents. But a few hours before his arrival in San Francisco, the documents show, an analyst from the National Targeting Center sent an email to the TTRT at the airport requesting that Gach be detained and questioned. Emails show the agents discussing “open source” intelligence about the artist before his detention — presumably information compiled from public social media profiles and websites that led to him being flagged. While names and personal information are redacted, Gach and his lawyer reviewed the documents and confirmed he was the subject of the emails.

“Based on some of the info we found in open source, he may be uncooperative,” the analyst wrote to a TTRT supervisor shortly before Gach was detained. “Interesting character though. We’re looking forward to reading the closeout!”

“I have no idea what that means,” Gach said, after reading the emails. “I’m a practicing artist and I have a public presence. I give lectures and write articles.” Gach said he wonders whether the political nature of his work made him a target. A professor at California College of the Arts, he is also founder of the Center for Tactical Magic, an art collective that frequently criticizes U.S. policy, focusing on such issues as government surveillance, civil liberties, and police brutality. At the time Gach was detained, President Donald Trump had recently issued a controversial travel ban aimed at travelers from predominantly Muslim countries. But Gach was flying from Belgium, which wasn’t included in the ban.

After Gach unlocked his cellphone and handed it over to be searched, the agents finally let him go. Shortly thereafter, Gach filed a complaint against CBP regarding the invasive search with the help of the ACLU and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a privacy watchdog organization. But to date he’s received no response, he said, as to why he was detained or what was done with the information collected from his cellphone.

After viewing the documents, Adam Schwartz, a senior staff attorney with EFF who helped file Gach’s complaint, said it looked like the TTRT agents were on a “fishing expedition.” “What is crystal clear is that they search people’s phones for any reason or no reason and that’s what they did to Aaron.” A CBP spokesperson said the agency does not comment on specific inspections.

Acting on Instinct

The Department of Homeland Security is not only the country’s largest law enforcement presence, it has also become America’s largest collector of domestic intelligence, said Rachel Levinson-Waldman, deputy director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

“The NSA gets a lot of attention and rightly so, especially post-Snowden,” said Levinson-Waldman. “But if you think about DHS, it really dwarfs any of the other agencies. It is just massive, and it is holding tons and tons of data.”

Unlike other law enforcement or intelligence agencies, CBP has been given the authority by Congress to conduct warrantless searches, which it uses to collect enormous amounts of personal information, often from U.S. citizens. Within 100 miles of any U.S. land or coastal boundary, CBP can detain, question, search, and seize property with fewer restrictions than law enforcement in the interior of the country. The area encompasses some 200 million people and some of the country’s largest cities, including Houston and New York City.

“They can’t just detain any person on the street with essentially no pretext and question them,” said Scarlet Kim, one of the ACLU lawyers who filed the FOIA lawsuit. “But at the border where the restrictions are much looser … it becomes this zone where they can pump people for information.”

The TTRTs are an extension of Homeland Security’s massive push to collect intelligence about people on U.S. soil and those abroad applying for visas to enter the country. The task force first came to the attention of the ACLU in 2017, according to Kim, when a Somali man and lawful permanent resident, Abdikadir Mohamed, was detained by TTRT agents and interrogated at John F. Kennedy International Airport. The Intercept wrote about Mohamed’s case and the nearly two years he spent in immigration detention before a judge determined that the TTRT agent had had no valid reason for detaining him.

The same year Mohamed was stopped at the airport, Homeland Security officials briefly mentioned the TTRTs twice in testimonies before Congress. The special units work at some of the nation’s largest border crossings and airports, they testified, and look for travelers identified within the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Database, commonly known as the watchlist, or for those “suspected of having a nexus to terrorist activity.” TTRTs denied more than 1,400 people entry into the United States in 2017, testified Todd Owen, then-executive assistant commissioner for the Office of Field Operations at CBP, during a subcommittee hearing for the House Committee on Homeland Security.

Kevin McAleenan, then-commissioner of CBP, said in a 2018 interview with a military publication that the TTRTs could target anyone for questioning. “The Tactical Terrorism Response Team concept was a conscious effort … to take advantage of those instincts and encounters that our officers have with travelers to make decisions based on risk for people that might not be known on a watch list, might not be a known security threat,” he explained. One of the goals, said McAleenan, who would go on to become acting secretary of DHS, was that the agents make “watchlist nominations that devolve from a good interview at the border.” The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment about CBP agents using the interrogations to nominate people to watchlists.

“They have free rein to target folks that have never presented a security threat or red flag for the government — even put them on a terrorist watchlist,” said Kim, who added that the most surprising revelation from the documents was the number of U.S. citizens — more than 180,000 — who were questioned by TTRTs between 2017 and 2019. At least 14 of those U.S. citizens were ultimately denied entry into the United States. The reasoning behind the extreme measure is redacted in the FOIA documents. When CBP was asked under what circumstances TTRTs could deny entry to U.S. citizens, the agency declined to comment, issuing the following written statement instead: “Applicants for admission bear the burden of proof to establish that they are clearly eligible to enter the United States.”

The limited reporting that has come out about TTRTs suggests that CBP’s use of the secretive units has at times been politically or ideologically motivated. In May, ProPublica wrote about two U.S. immigration attorneys in El Paso, Texas, who were interrogated by the terrorism unit in 2019 and asked about their religious beliefs and opinion of Trump. Documents provided to ProPublica showed that agents suspected them of assisting Central American migrants traveling in caravans to the U.S. border, which DHS surmised were being organized by “Antifa,” an obsession shared by Trump and right-wing media at the time. Several other U.S. activists, journalists, and attorneys were also targeted in a secret database for interrogation at the border, and dossiers were created regarding their activities.

Another concern is racial profiling, since agents often rely on their “instincts,” as McAleenan described, rather than probable cause when detaining people. Gach noted that while waiting to be questioned by TTRT officers, he appeared to be the only white person among the two dozen other travelers who had been detained. “My biggest concern is that this kind of thing is happening unchecked to a lot of people who I think are more vulnerable than me,” Gach said. “There has to be some sort of accountability.”

After U.S. citizens, the top three nationalities targeted by TTRTs, according to the documents, were Canadians, Mexicans, and Pakistanis. For those denied entry to the United States, the top three included Canada, Iran, and Venezuela. The documents do not break down the denials or encounters by racial category.

Database Upon Database

The Intercept and Type Investigations submitted several questions to CBP about the task force, including whether the agency keeps its own list of potential terrorist suspects, what the agency does with the information it collects from electronic device searches and interrogations, why it targets so many U.S. citizens, and whether it has protocols in place to prevent racial profiling.

The agency declined to comment other than to reply in a written response that CBP “strictly prohibits profiling on the basis of race or religion.”

While CBP would not elaborate on its intelligence gathering, much of what it collects goes into a massive database it administers called the Automated Targeting System. The TTRT units often act on requests from CBP’s analysts to interrogate certain individuals at airports and land borders to gather more information about them and their associates. Much of this information is poured back into the burgeoning ATS database, which includes data from at least 14 other databases within DHS, the FBI, and the Department of Justice, including immigration enforcement data, as well as the Terrorist Screening Database and other watchlists, according to a 2019 DHS Data Mining Report to Congress. CBP also continuously monitors social media sites, according to a 2019 DHS Privacy Impact Assessment.

“The DHS databases are sort of like Escher’s stairs. It’s database upon database and they all seem to interrelate,” said Levinson-Waldman, who is co-authoring a series of reports on DHS, privacy, and civil liberties for the Brennan Center. “I don’t even know how it would be quantified. I don’t think DHS has even quantified it.”

All this information is used to search for patterns and associations based on secretive algorithms to create a “risk assessment” for every foreign traveler and U.S. citizen, said Levinson-Waldman. CBP can change its criteria for risk at any time, which target certain travelers for increased scrutiny. Levinson-Waldman cited hypothetical examples of people who might be flagged, ranging from married couples traveling from Turkey to anyone who has flown from Syria. “We really have no idea,” she said.

“It’s essentially a black box algorithm,” said Hugh Handeyside, an attorney with the ACLU who has spent years litigating civil rights issues around the “no-fly list,” which bans anyone on the list from flying over or within U.S. airspace. But unlike the no-fly list, Handeyside said, there is no redress process for anyone flagged by the ATS database to challenge incorrect information or clear their name. Once targeted, a person can be subjected to interrogation and invasive searches every time they travel, and in a worst-case scenario, be prevented from entering or leaving the United States. “It imposes all of the same consequences, essentially, as placement on a watchlist but there’s not even a nominal redress,” he said.

Gach said he hasn’t been stopped again in the few times he’s traveled since the incident in 2017. But as a precaution, he now has a computer and cellphone that he only uses for travel. “Those are costs I can’t easily afford but I felt it was a necessary measure,” he said. “I feel anxious and apprehensive every time I travel now.”