INIAKUK LAKE, Alaska — Iniakuk Lake is five miles long and a mile wide. Located inside the Arctic Circle just south of the Brooks Range, it sits in the middle of one of the largest roadless regions in North America. It is not uncommon to see bears and wolves roaming its sandy shores, especially in the pre-dawn light of a northern summer. Thick black spruce forest dominates the hillsides, and many of the nearby peaks remain unnamed. In mid-June, I walked with John Gaedeke, the owner of an exclusive tourist lodge at Iniakuk, to a spot about a mile from the lake’s outlet where the future of his family business hangs in the balance.

That, Gaedeke said, pointing toward the confluence of two rivers, a branch of the Alatna and the Tobuk, “is where the bridge proposal is.”

For nearly 50 years, Gaedeke’s family has catered to visitors willing to pay upward of $10,000 for the pleasure of spending three nights in what is considered one of the quietest places on earth.

John Gaedeke is a lodge owner at the remote, fly-in Iniakuk Lake Wilderness Lodge. The proposed Ambler Road would pass a few miles from the south end of the lake that the lodge sits on.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

“If you had dust clouds from the road down there and then the noise of the traffic it would be just like any other place,” Gaedeke told me. “It would pretty much be the end of business as we know it here.”

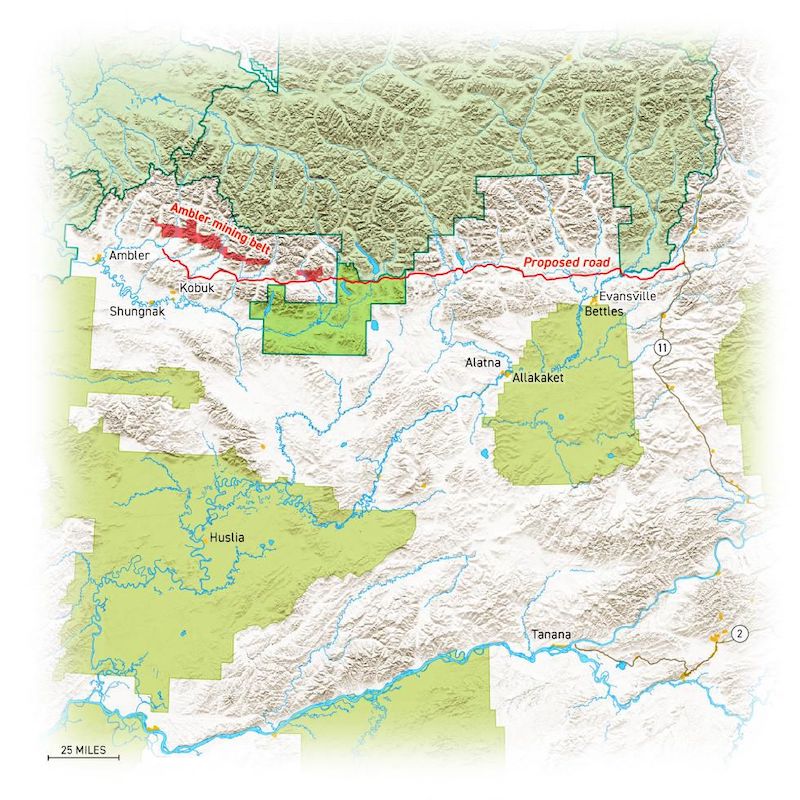

Last summer, in the final months of the Trump administration, the Department of the Interior approved a 211-mile industrial access road that would run across much of interior Alaska to the Ambler mining district, a massive but remote deposit of high-grade copper and zinc. Ambler’s underground riches are so highly prized that when Gates of the Arctic National Park was created in 1980, the Alaska delegation made sure a provision for possible road access across the park was written into the legislation. The last time a road of this size was built through an undeveloped part of Alaska was in the early 1970s when the 414-mile Dalton Highway was put in to connect Prudhoe Bay, on the north slope of Alaska, with an existing network of roads near Fairbanks.

Ambler Road is similarly ambitious — and equally fraught environmentally. The road would ultimately enable the extraction of more than 43 million tons of copper and zinc over at least 12 years, creating thousands of jobs, say the Ambler mining interests, and pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into state coffers. But even before the first load of copper is removed, the road itself would irrevocably transform a vast region of Alaskan wilderness, potentially disrupting the migration patterns of the state’s largest caribou herd and polluting some of the state’s most important spawning grounds for salmon and whitefish. It would also threaten the way of life of Alaska natives who have lived in the region for thousands of years and depend on those resources as their primary food source.

The Alatna is “the main tributary for life and water down to all of the people on the Koyukuk River,” Gaedeke said. “So they’re pretty worried about that crossing.”

It was on similar grounds that President Joe Biden, on his first day in office, put a temporary moratorium on oil and gas development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The Trump administration had rushed the lease sale, downplaying scientific evidence of the social and environmental impacts. Biden’s dramatic reversal of a project Donald Trump had made a keystone of his energy policy was celebrated by the conservation community, who saw it as a clear signal that Biden was prioritizing the environment over the needs of industry.

But the Biden administration has been conspicuously silent on the Ambler Road project, showing no intent to interrupt the approval process despite vocal opposition from multiple groups in Alaska. Indeed, when it comes to mineral and rare earth production, Biden and his predecessor are closely aligned. If the road is built, it will pit the administration’s green-energy agenda against promises it has made to protect ecologically sensitive regions.

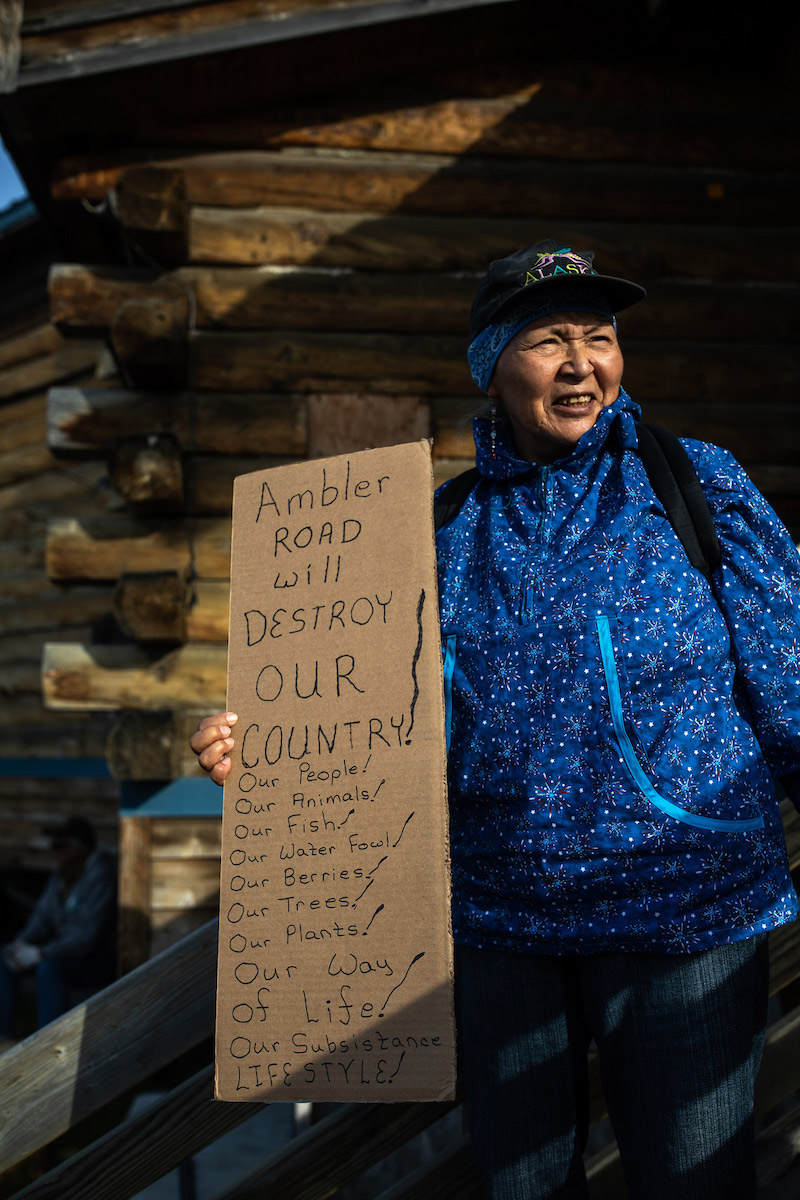

The Ambler Road would not only impact Gaedeke’s family business, it would also threaten the way of life of Alaska natives who have lived in the region for thousands of years.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

In early June, the Biden administration announced that it was establishing a task force to address the supply of critical minerals and emphasized the need to scale up domestic production to “meet national and global climate goals.” Large quantities of rare earth metals and other minerals, including copper, are needed for electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines and batteries — all critical to achieving the administration’s ambitious green-energy goals. Over the next few decades, global demand for copper is expected to soar by as much as 270 percent, with the needs of manufacturers outstripping supply by 2050, according to one estimate.

These goals, however, are banging up against other promises. Biden signed a presidential memorandum on January 26 that reaffirmed his commitment to engage with tribes on development projects that would affect their land and way of life. Deb Haaland, the first Native American secretary of the Interior, has stressed the importance of that consultation process. “I want the era when tribes were on the back burner to be over,” she told a group of Indigenous journalists in March on her first day in office.

The Tanana Chiefs Conference, a consortium of 37 federally recognized tribes, many of them in the affected region, says the previous administration already failed the consultation test. The conference passed a resolution last year, noting that the road “will have a negative impact on Native subsistence ways and lands,” and that “mining for mere financial gain poses new threats to the survival of our natural and cultural resources.” In high-level meetings with the Department of the Interior, the White House Domestic Policy Council and other federal agencies in the last week of July, the group called on the department to revoke the right of way permit granted under the Trump administration and to halt summer fieldwork.

A pair of sled dogs stand at Iniakuk Lake as the sun sets around 1 a.m. in June.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

Opposition to the road among Alaska Natives, who make up about 15 percent of the state’s 731,000 population and are spread across a vast area rather than concentrated on reservations, is not unanimous. Some Native villages closer to the mining district are more supportive of the project and, one of the state’s largest and most powerful Native corporations, has partnered with the mining company seeking to develop the copper and zinc deposit. But opponents of the road have been vocal.

Five Native villages along the proposed road corridor and the Tanana Chiefs Conference have sued the Department of the Interior over its handling of the Ambler Road environmental impact statement, arguing that the department did not uphold its obligation to meaningfully consult with tribes. A second lawsuit, brought by nine environmental groups, alleges that the Department of the Interior did not have key information it needed, including detailed mapping of wetlands for a 50-mile portion of the road, to adequately carry out its analysis. The environmental groups are also calling for the right of way permit for the road to be revoked.

After meeting with the Department of the Interior and White House officials in July, Natasha Singh, general counsel for the Tanana Chiefs Conference said, “We hope Biden is not going to defend President Trump’s failed process.”

But that is precisely what the Biden administration appears poised to do.

Officials at the Department of the Interior have continued to process permits for predevelopment work this summer, including geotechnical drilling at proposed bridge sites on three major rivers, allowing the road construction to move toward its intended start in 2024. That work continues in spite of the allegations in both lawsuits that the Trump administration cut corners in the environmental review process to hasten approval of the road project, skipping important steps.

But the Trump administration went further. According to documents obtained by POLITICO and Type Investigations, and interviews with several current and former Interior employees, the Bureau of Land Management Alaska’s state director, who was hired in 2019 and previously worked for GOP Representative Don Young, downplayed the significance of subsistence hunting and fishing during the Ambler environmental review and pushed career employees to modify their findings that showed the potential for widespread environmental damage. Instead, he urged them to stress the project’s potential benefits to the economy and public health. One Interior Department employee who worked on the environmental impact statement said that as a result of the state director’s involvement, environmental safeguards in the final document were significantly watered down.

“He sanitized it,” the employee, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, told me.

Haaland, who said during her confirmation hearing that the United States needed to reduce its dependence on foreign suppliers of critical minerals and that mining can be done responsibly, declined to be interviewed for this story. The Interior Department also declined to answer detailed questions about the handling of the environmental impact statement, and a spokesperson said the department had “no comment on ongoing litigation.”

P.J. Simon, president of the Tanana Chiefs Conference, who grew up in Allakaket, one of the villages suing the Department of the Interior, says the department should start over. “We know and they know they violated our rights,” Simon said. “But right now, for whatever reason, they’re not addressing this lawsuit.”

"We know and they know they violated our rights.” —P.J. SimonImage: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

The administration’s approach reflects the policy dilemma it now confronts.

Ambler, and other projects like it, represent an opportunity to bolster domestic mineral production, which the administration sees as crucial to transitioning away from a fossil fuel-based economy and reducing dependence on foreign suppliers. And these projects are deeply popular with politicians, such as Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, whose support was key to Haaland’s confirmation.

But federal courts have made clear that those priorities do not outweigh the need to adhere to the environmental review process. On August 18, a judge in Alaska voided permits for a major ConocoPhillips oil and gas development project on the North Slope, also backed by the Biden administration, because the review process was deeply flawed. The same judge has ordered the Department of Justice to prepare a brief by mid-November in defense of the impact statement for Ambler Road.

A History of Environmental Pollution

Officials have known since the 1960s that the Ambler mining district contained substantial reserves of copper, zinc, gold, silver, and cobalt — one of the richest deposits of minerals in the world. But it wasn’t until 2010 that the state began to actively pursue the road project. Partly in response to the crash in oil prices in 2009, Alaska’s political leaders began to advocate for increasing production of minerals as a way to revive the economy; what Governor Sean Parnell called the “Roads to Resources,” which included Ambler and several other mines in the state, was part of that strategy.

But getting federal approval was difficult from the very beginning.

The first application submitted in late 2015 by the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, the state’s publicly owned development corporation, was rejected by every federal agency involved in the analysis, largely because it lacked sufficient detail. The revised application, however, received a significant boost from the Trump administration, which initiated the environmental review process just weeks after taking office. According to publicly available calendars, the mining companies that had worked with AIDEA had early and frequent access to top Department of the Interior political appointees. (Ambler Metals, a joint partnership of a Canadian company and an Australian one, has retained former Interior Secretary David Bernhardt’s firm to lobby on its behalf and spent $110,000 in the second quarter of this year.)

The 211-mile Ambler Road would cut across one of the largest roadless areas in North America, crossing hundreds of rivers and streams, and potentially impacting caribou migration patterns and some of Alaska's most important salmon and sheefish spawning streams. Alaska Natives who have lived in the region for thousands of years are concerned that the road will undermine their way of life and threaten the subsistence resources they depend on. Five villages, including Allakaket and Alatna, have sued the Department of Interior over its handling of the environmental impact statement and approval of the road project. Image: Politico

For the Trump administration, which trumpeted its intentions to mine and drill in even the most ecologically sensitive regions of Alaska, the appeal of Ambler Road was clear. Trump officials recognized that development of rare earth metals and other minerals was one way to revive U.S. manufacturing, a centerpiece of its campaign agenda. Moreover, the rare earths market has been dominated by China for decades, and Trump saw domestic production as a way to push back against a major rival.

In 2017, the Trump administration ordered the U.S. Geological Survey, a bureau within the Interior Department, to publish a roster of minerals considered critical to U.S. economic and national security. One year later, USGS put out a list of 35 such minerals and described Alaska in particular as having a “wide variety of mineral commodities” vital to “national defense, renewable energy, and emerging electronics technologies.” The rush to pull precious minerals out of Alaska remained a priority for the Trump administration until the president’s very last days in office. On January 19, the Department of the Interior announced that it was lifting restrictions on mining development on 28 million acres of land in the state. (The Biden administration has since delayed this decision for two years pending further review.)

In the face of national security concerns and demand for “green technology,” another road in a state the size of Alaska might not seem like a big deal. But Ambler would bisect what is considered some of North America’s most remote wilderness lands. It would permanently destroy more than 1,400 acres of wetlands and cross nearly 3,000 streams, according to an Army Corps of Engineers analysis. The road would also come within a few miles of Walker Lake, a federal landmark in Gates of the Arctic National Park known for being one of the quietest places in North America, and just a quarter mile from Nutuvukti Fen, a rare wetland ecosystem that has been described as “an Arctic ‘Everglades’ of sorts, much smaller but a wellspring of nutrition and enrichment to that region of the Brooks Range.”

“It is one of the last places on the continent where we haven’t built roads,” said Alex Johnson, Alaska Senior Program Manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, which opposes the development project. “A road is a misnomer: It’s an industrial mining transportation corridor.” Johnson and other critics of the project worry that Ambler Road will not only provide access to mines in the Ambler district, but also open up thousands of acres of state and Native land along the road corridor to further exploration and development. Mining companies have already expressed interest in potential reserves outside of the Ambler district.

Whatever one calls it, the environmental consequences of open-pit mining and the roads needed to service an enterprise as large as Ambler are well understood.

Irene Henry outside the Allakaket Tribal Hall after a village-wide meeting on the proposed Ambler Road.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

The world’s largest open-pit zinc mine, known as Red Dog, is in northwest Alaska, about 150 miles from the Ambler district. It is often touted as a model for the Ambler project in part because, like Ambler, it involves a partnership between an Alaska Native corporation and the private sector. But according to data compiled by the state of Alaska and reviewed by Susan Lubetkin, a statistician and independent researcher, in the last 25 years, since the state began keeping records, there have been more than 450 transportation-related spills associated with the Red Dog mine, including the release of 250,000 pounds of zinc concentrate in 2012. These spills took place along a 55-mile gravel access road that connects the mine to a port on the Chukchi Sea, which is only open about 100 days a year; the road has been declared a contaminated site by the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation.

- 'It is one of the last places on the continent where we haven’t built roads.' —Alex Johnson, Alaska Senior Program Manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, which opposes the development project.

Ambler Road would be more than four times as long, multiplying the chances of accidents and spills. During peak production, according to the Bureau of Land Management, there would be approximately 168 truck trips a day. “With nearly 50 years of industrial truck traffic planned on the Ambler Road and with transport of fuel, chemicals, and ore concentrate year round and often in the dark,” the bureau wrote in its environmental impact statement, “it appears likely spills would occur despite precautions.”

Hard rock mining in Alaska has also done considerable environmental damage, according to a 2020 analysis by the environmental group EarthWorks. The study found that four of the five largest mines in the state, including Red Dog, have frequently contaminated nearby waterways and violated the Clean Water Act. “Looking at the track record of major modern hard rock mines in Alaska the water quality impacts are common,” said Bonnie Gestring, the Northwest Program director for EarthWorks and author of the report on Alaska.

The Biden administration has said it will adhere to the highest environmental standards when it comes to mineral development and recently announced that it would seek to permanently block gold and copper mining in the Bristol Bay watershed, one of the state’s most important commercial salmon fisheries. But the administration is not applying the same standard to the Ambler Road project and mining development, which pose similar risks. Construction of the road alone would leave a massive industrial footprint. Fifteen million cubic yards of gravel — a quantity that would cover an area roughly 9,000 acres large to a depth of one foot — would be mined from more than 40 different sites along the road corridor. High levels of naturally occurring asbestos in the region have raised concerns among critics of the project and local residents that the building of the road and subsequent truck traffic could pose long-lasting risks to human health and the environment. Four permanent maintenance stations, 12 communication towers and three airstrips would be installed.

The road would run through the middle of the Western Arctic Caribou herd’s migration corridor and also possibly impact the Teshekpuk and Ray Mountain herds, still an important cultural and subsistence resource for local Native communities. More than two dozen bridges, thousands of culverts, and potential spills or accidents could irreparably harm critical spawning habitat for sheefish (a kind of whitefish) and salmon, according to the Bureau of Land Management’s own analysis.

It would also be built atop increasingly unstable permafrost that is susceptible to rapid thaw and subsidence in an area warming two to three times faster than the rest of the planet, according to a recently published report from the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme. The road development itself, by removing vegetation and clearing the land, would accelerate that process according to the environmental impact statement.

And there’s the unresolved question of whether the road would eventually be opened up to public access for hunting and recreation as happened with the Dalton Highway. Critics of the Ambler Road project see this as an inevitable outcome — even though the state has promised it will remain a private access road — and fear that opening it to further use will have profound impacts on the subsistence resources and the environment.

Mike Spindler, a biologist with The Wildlife Society, an environmental advocacy group, who served until 2017 as manager of the Kanuti National Wildlife Refuge, about 12 miles south of the proposed roadway, said the mitigation measures for the project are insufficient to prevent widespread environmental and cultural damage.

Spindler is convinced the road will eventually be opened to the public and that it will be a pathway for non-native invasive species (a phenomenon that has been seen along the Dalton Highway), as well as a massive financial liability for the state. Some doubt that the road will ever get built and believe the state is wasting tens of millions on a boondoggle; others say the promise that the state will recoup its investment through tolls is unlikely.

“What I see with this thing, if it gets built, is a train wreck,” Spindler said.

AIDEA declined to respond to questions for this story. Ambler Metals did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

One of the central arguments in both of the lawsuits brought against the Department of the Interior is that the environmental impact statement was completed without rudimentary information needed to properly evaluate the road’s impacts. The state has yet to do cultural resource surveys, comprehensive wetland mapping for the first 50 miles of the road, baseline air quality assessments, or sampling of soil to determine the location and quantities of naturally occurring asbestos. Those suing the department argue that much of this work should have been completed before the impact statement was approved. But under an Interior Department directive during the Trump administration that environmental impact statements be completed within a year, much of the baseline work was never done. Even the precise location of the proposed roadway is still a work in progress.

Said Bridget Psarianos, an attorney with Trustees for Alaska, the lead plaintiff in one of the lawsuits: “They’re pretty much drawing lines on a map because they don’t know what’s out there.”

Survival Without Supermarkets

Allakaket is a small Native village of just over 200 people on the banks of the Koyukuk, Alaska’s sixth largest river. When I met P.J. Simon there in June, one of the first things he mentioned was a tributary known as Henshaw Creek, where, in some years, more than a quarter million chum salmon have been known to spawn. Simon lives in Fairbanks now, but he grew up in this part of Alaska and his parents still live there. His family used to set up a seasonal fish camp at Henshaw Creek, and it remains an important resource for the community. It is also one of several salmon spawning streams that would be crossed by Ambler Road.

Late one afternoon, Simon took his father’s flat-bottomed aluminium boat and we made our way about a mile up the Koyukuk to Henshaw Creek, its banks lined with river grass and willows. Eventually we pulled ashore at a spot where the crystal-clear water was a foot or two deep and the creek had narrowed considerably. The cold waters fed by snowmelt and glaciers from the Brooks Range have kept the water temperature relatively stable. Each year, salmon swim more than 500 miles from the mouth of the Yukon River where it meets the Bering Sea just to reach these pristine waters and lay their eggs in the pebbled creek bed.

P.J. Simon sets a net out across a slough of the Koyukuk River to capture returning whitefish and early chum salmon. Allakaket residents worry that road construction and mining spills could lead to polluted rivers in the region.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

In 2017, 360,000 chum salmon — 15 percent of the entire Yukon River run — were counted in July and August at a weir on Henshaw Creek, but since then those numbers have declined dramatically due to a variety of factors, including warming waters and overfishing at sea. In 2019, a spell of hot weather led to a salmon die-off on the Koyukuk before the fish even reached Henshaw Creek. This year, the chum salmon run on the Yukon was the lowest ever recorded, and the state was forced to shut down all commercial and recreational fishing in the region. Counts at Henshaw were abysmally low. Packaged salmon had to be flown in to feed villages throughout the region.

“In Fairbanks, people can get their food stamps and go to Safeway or Freddy’s,” Simon said. “Out here there’s nothing like that.”

According to the Bureau of Land Management’s own analysis, Henshaw Creek is one of several streams that would be “vulnerable to spills and other contamination.” Even small changes in water quality, the bureau concluded, “could have substantial impacts on fish populations.” Salmon have an acute sense of smell, and even tiny increases in copper concentrations, according to a 2003 study, can impair the fish’s nervous system, harming its ability to migrate and avoid predators.

It is only relatively recently that Koyukon Athabascans like Simon, who have lived in this part of Alaska for thousands of years, established permanent year-round settlements. (There are eight villages and about 600 people in the entire Koyukuk River drainage which covers about 35,000 square miles.) Up until the early 1900s, the Native inhabitants lived semi-nomadic lives, moving with the seasons, “always looking for places where there were game and fish in abundance,” as Sidney Huntington, a well-known Native leader, noted in his 1993 memoir of life on the Koyukuk. But even living more settled lives, they remain dependent on the rivers and forests for survival, sometimes traveling for days to hunt dall sheep or caribou. According to data collected by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the average household in Allakaket, one of the eight villages, consumes close to 2,500 pounds of fish and game annually, about 70 percent of it salmon and whitefish.

It’s for this reason that federal lands legislation passed in 1980 includes an entire section, referred to as 810, which lays out a multistep process for identifying and addressing impacts to subsistence. An “810 analysis” is part of most environmental reviews in Alaska, and if it is found that development will “significantly restrict” subsistence use, the Department of the Interior must hold additional hearings in the affected villages and in some cases adopt measures to ensure that traditional land use practices are not adversely impacted.

Under the Trump administration, the role of subsistence in the environmental review process in Alaska was largely viewed as a barrier to development. Political appointees openly questioned decades of research on the impact of oil and gas development on caribou behavior and pressured the Interior Department to scrap its criteria for assessing impacts. The department also disbanded the Bureau of Land Management Alaska subsistence advisory panel, established in 1998 and made up of a cross-section of stakeholders, and transferred its duties to a working group focused on oil and gas development.

“Too Much Emphasis on Subsistence”

Subsistence was a target for Chad Padgett, the newly hired Bureau of Land Management Alaska state director. Under Padgett’s leadership the bureau quietly revised policy guidance on implementation of section 810, slashing the document from 40 pages to about 10, according to an Interior department employee who saw both versions. The memorandum was signed by Padgett this spring, but following inquiries from POLITICO and Type Investigations the changes were never adopted.

Padgett, who spent 10 years working for congressman Don Young, was brought on in early 2019. He had little experience in public lands management and, after he was hired, E&E News reported that he had been “hand-picked” by Joe Balash, a senior-level Interior Department political appointee from Alaska. (Balash had served as Alaska Senator Dan Sullivan’s chief of staff.) The Ambler Road project was one of a handful of top priorities for the department, along with selling oil leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and expanding oil and gas development in the National Petroleum Reserve.

Warren Douglas and Caroline Ticket of Shungnak, seen picking blueberries, are opposed to the Ambler Road development. “All that toxic water, where’s it going? It’s going to us. We’re downriver. It’s gonna kill off all the fish,” says Douglas.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

“It was important for the state,” one Department of the Interior employee who was involved in the early stages of the Ambler environmental impact statement told me. “The administration was being very receptive to the needs of the state.”

Padgett took a personal interest in the Ambler environmental impact statement. The Bureau of Land Management state director would normally be briefed on such a project but allow career employees to carry out their work unimpeded. One Interior Department employee involved in the process told me that Padgett paid an “unheard of level of attention to the EIS” and went over proposed mitigation measures with a “fine-tooth comb.”

According to documents obtained by POLITICO and Type Investigations and interviews with four Interior Department employees, Padgett was dismissive of the project’s potential impact on subsistence hunting and fishing and pressured career employees to modify their language and even delete entire sections addressing the subject. Padgett heavily marked up a draft of the final environmental impact statement, a copy of which was obtained by POLITICO and Type Investigations. “Far too much emphasis on subsistence impacts,” he wrote on the cover page. “Too little positive impacts on economy & public health.” He also chastised the agency for highlighting risks associated with naturally occurring asbestos and the potential degradation of native plant species and the ecosystems they depend on.

Padgett suggested deleting an entire three-page section reviewing the contemporary social science research on the impact of roads and development on subsistence hunting. He also crossed out another long section looking at what can happen to Native communities when they lose access to traditional harvesting areas, which the Bureau of Land Management wrote can have “long-term or permanent effects on the spiritual, cultural, and physical well-being of the study communities.”

In the end, these sections were not deleted but smaller changes based on Padgett’s edits were incorporated. At least three sentences on impacts to wildlife including fish, birds and moose were cut. One sentence that said the road “could affect fish species abundance and distribution not only in individual streams but across the region” was deleted. And in several cases, emphasis was shifted to imply that negative impacts were less certain and potential positive outcomes more likely than the bureau’s analysts had initially stated. In one instance, for example, analysts wrote that leaching of acid rock into waterways “would” affect the quality of sheefish and salmon habitat. Padgett had them change it to “could.”

But Padgett’s involvement went further. After an impact statement is completed, the department still has to publish a final record of decision, which includes measures designed to reduce impacts to the environment and, in cases where wetlands will be impacted, typically some form environmental remediation elsewhere, known as compensatory mitigation, to offset damages. According to the Interior Department employee in Alaska, Padgett modified the recommended series of environmental protections included in the record of decision so that they would be less onerous to the state. He did this by weakening proposed stipulations and by inserting language that would allow the state to sidestep various mitigation measures.

“In effect, what they did was they watered down quite a few of the stipulations for Ambler Road,” the employee told me. “Under Chad’s leadership, they were changed to be more friendly to the proponent.”

A Bureau of Land Management spokesperson declined to comment on questions submitted to Padgett and the agency’s Alaska office. (In August, Padgett was reassigned to a detail at BLM headquarters and resigned soon after. He has since joined Senator Dan Sullivan’s staff as Alaska state director. Attempts to reach Padgett through Sullivan’s office were unsuccessful.)

In another move that caught environmental groups off guard, the Bureau of Land Management and the Army Corps of Engineers, which issues permits when wetlands are involved, determined that no compensatory mitigation measures would be required, a process whereby project applicants must restore or protect habitat elsewhere to offset unavoidable damage associated with the development. According to Psarianos, the Corps had implied all along that it would include compensatory mitigation to make up for the nearly 1,500 acres of habitat that will be permanently destroyed and the more than 17,000 acres of wetlands that will be indirectly impacted as a result of the road project. As late as March 2020, just a few months before the record of decision was published, the Corps and a consulting firm hired by AIDEA were discussing the necessary measures. Even the Environmental Protection Agency, which submitted comments on the impact statement, was inquiring about the status of the compensatory mitigation plan up until the last minute.

But when the final document was released compensatory mitigation had been removed, even for more than 100 acres of impacted wetlands in Gates of the Arctic National Park. Psarianos said conservation groups were shocked by the omission. Even for projects with a much smaller footprint — Psarianos cited a seven-mile road that was part of an oil and gas development on the North Slope — some sort of compensatory mitigation is standard. “It’s unprecedented by all accounts,” she said.

The Army Corps of Engineers said it does not comment on projects in litigation.

The final record of decision was issued on July 23, 2020. In a press release, the Department of the Interior called it a “game changer for our nation’s ability to secure American prosperity and national security.” On January 6, the same day the Interior Department sold oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, it also signed a 50-year right-of-way agreement with AIDEA giving the state permission to build a road across federal lands including Gates of the Arctic National Park. AIDEA has since committed $35 million for predevelopment work, which will be matched by Ambler Metals. And an additional $13 million has been earmarked for this summer’s field surveys and geotechnical drilling.

- Ambler would bisect what is considered some of North America’s most remote wilderness lands. It would permanently destroy more than 1,400 acres of wetlands and cross nearly 3,000 streams, according to an Army Corps of Engineers analysis.

Since Biden took office, the Bureau of Land Management Alaska has continued to advance the Ambler Road project. In July the bureau approved AIDEA’s summer work plan despite vocal opposition from tribes and the Tanana Chiefs Conference who say they were not adequately consulted or given enough time to review the final document. The tribes had wanted AIDEA to complete more of its federally mandated cultural resource surveys for the entire project area before beginning any ground disturbing activities. But the bureau went ahead and authorized a piecemeal approach to the survey work that would allow the state to begin drilling dozens of 50-foot holes to evaluate bridge crossings on three major rivers: the John, the Wild and the Koyukuk.

“TCC and its members continue to be dismayed and frustrated at the manner in which this 2021 work plan review process has been handled,” Simon wrote in a letter to the Bureau of Land Management in late June. The bureau, he wrote, was “only grudgingly willing to listen to Tribal concerns,” and had taken steps to “stringently limit their the tribes opportunities for consultation.”

Whose Voice Will Be Heard?

While Haaland has made it clear that involving tribes in the federal decision-making process is a top priority, she has also said she believes mineral development can be done responsibly and that she will do everything in her power to ensure that Alaskans “have the opportunities they need.”

Murkowski, who provided a crucial vote in support of Haaland’s confirmation, said she did so with the expectation that Haaland would fulfill her promise, “Not just on matters relating to Native peoples, but also responsible resource development and every other issue.”

A 1 a.m. sunset on the edge of Allakaket on the first morning of summer.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

But it’s not a simple matter to determine who speaks on behalf of Native villages, especially when it comes to a project as large and complex as Ambler Road.

One of the most powerful voices in the debate over Ambler Road is the Northwest Arctic Native Association, commonly referred to as NANA, one of Alaska’s 13 regional Native Corporations. NANA has supported the mining development and owns a large percentage of the subsurface rights in the Ambler mining district, including the Bornite copper and cobalt deposit, one of four mine sites where exploration work has begun. NANA, one of the largest employers in this part of Alaska (it owns the Red Dog mine), represents shareholders in the three villages closest to the district: Ambler, Kobuk and Shungnak.

In 2004, NANA formed a partnership with Ambler Metals (then known as NovaGold) that would give them the option to participate as a joint-venture partner or receive royalties from any mining activity. (Ambler Metals, established in 2020, is a joint venture between Trilogy, a Canadian company, and South32, based in Australia.) Willie Hensley, a former NANA executive and prominent Native leader from Kotzebue, the largest city in the Northwest Arctic Borough, who served in the state Legislature, is a member of Trilogy’s board of directors. Other NANA board members and shareholders have spoken publicly in favor of the road and the mining project.

Still, the politics surrounding resource development in the villages near the mining district are divisive, with various entities — the city administration, tribal councils, borough government, native corporations and even families — sometimes at odds with one another.

In the village of Ambler, for example, a messy dispute has broken out over the leadership of the tribal council, with a pro-development faction taking over after holding a controversial plebiscite election in December. Those results have been upheld in a recent ruling by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a bureau within the Department of the Interior, but are being challenged by the original council members who have now been unseated. At a meeting during the recall vote in December, Miles Cleveland, a former NANA board member and the new leader of the tribal council, said the village stood to benefit from the mine and road. “We have a road that is being built to the east and a mine that is going to be developed here in the near future,” he said, according to a recording of the meeting. “We need to work together to get what we want out of those.”

In Shungnak, Crystal Ticket, whose children work in the mining industry and whose father and uncle have been involved in the Ambler Road study, said, “We need that road for access for future deliveries for goods and fuel. … It’s important for future generations to look forward to new opportunities. Hopefully, they’ll hire a lot of Alaskans and give them training.”

The village of Shungnak sits on the upper Kobuk River, about ten river miles downstream of the village of Kobuk and just under ten direct miles from the Bornite mine.Image: Nathaniel Wilder/Politico

The Ambler Road would terminate nine miles from the neighboring village of Kobuk, which has a population of about 140 people. Kobuk would be the closest settlement to both the road and the mining district, putting it at greater risk of environmental and social impacts. Even before the road reaches its end point, it would cross the Kobuk River in Gates of the Arctic, a federally designated wild and scenic river, and more than 20 of the river’s tributaries upstream. Meanwhile, the Bornite deposit, where exploration work has been ongoing, is just 13 miles by road north of the village, not far from a spring that supplies drinking water to local residents. If the area is fully developed — the environmental impact statement identifies four potential mines but there are dozens of prospective sites nearby — open-pit copper mines would threaten the Kobuk River, which supports the largest spawning population of sheefish in this part of Alaska.

Kobuk initially joined the TCC lawsuit challenging the Bureau of Land Management’s approval of the road. But the village recently withdrew from the litigation, despite ongoing concerns about the project’s impacts.

I had intended to visit the village to interview residents about their opinions of the road. But in late June, three days before I was scheduled to fly in, the Kobuk city administrator, Johnetta Horner, who is also a member of NANA’s board of directors, informed me that the trip had not been approved, citing Kobuk’s Covid restrictions. The city and tribal councils, she wrote, do not “agree with anyone coming into Kobuk at this time.”

This seemed like a surprising reversal because I had already gotten approval from the Northwest Arctic Borough — the regional governing body — to visit Kobuk, and Covid restrictions for fully vaccinated travelers had been lifted several weeks before. Residents and nonresidents alike, I was told, had been traveling to the village. With an extra day and a half to spend in Kotzebue, I requested a meeting with NANA representatives and even stopped by its office, a light blue two-story building overlooking the Chukchi Sea. The corporation told me I had to go through the group’s official communications department in Anchorage and refused to make anyone available to meet with me.

In a written statement, NANA said it had not yet taken a position on the road — though it openly supports the development of the mining district — and is “committed to protecting our lands for subsistence use and the responsible development of our natural resources.” NANA has, however, intervened on behalf of the state in both lawsuits challenging the Bureau of Land Management’s approval of the project.

- 'What I see with this thing, if it gets built, is a train wreck.' —Mike Spindler, a biologist with The Wildlife Society, an environmental advocacy group.

Meanwhile, opponents of the project are continuing to put pressure on Haaland to intervene in a process that appears to be moving ahead steadily. AIDEA says it will complete fieldwork over the next several years and begin road construction as soon as 2024.

Simon, the president of the Tanana Chiefs Conference, is hopeful that the voices of its members will ultimately be the ones that matter most. At a community meeting in Allakaket’s tribal hall in mid-June, he referred to Haaland as an “ally” and said the TCC had a lot of support in Washington. On June 30, the conference sent the Interior Department a formal letter asking the secretary to meet with its representatives in Fairbanks and to travel to one of its villages, “To ensure all tribal voices are raised.”

“If Secretary Haaland can come here then that would be a really big thing,” Simon told the room of about 25 villagers. “With our lawsuit we can bring this to the president’s attention. He can, by the stroke of his pen, shut things down. So that’s what we’re hoping for.”

In addition to briefing federal agencies in July, the Tanana Chiefs Conference and leaders from the villages suing the Department of the Interior also met with Murkowski and members of her staff. According to several participants, Murkowski was engaged and listened carefully to what the tribal leaders had to say. More recently, though, Murkowski has pointed to the Ambler project as one that would benefit from the infrastructure bill passed by the Senate in August, which included measures to streamline permitting of critical mineral development. Biden has also embraced policies that would speed up domestic mineral production.

Murkowski’s office did not respond to repeated requests for comment. But her position on Ambler Road has been unequivocal. During Haaland’s confirmation hearing, Murkowski asked a pointed question about whether, as secretary, she would support and defend projects approved under the previous administration, including Ambler Road.

Haaland said she would “follow the law” and consult with Murkowski regularly. “Defending these specific projects would be critically important in following that law,” Murkowski replied.

Haaland had planned to visit Alaska in mid-September, but her office cancelled the trip early this month, citing “rising Covid rates.” A statement released by Haaland’s spokesperson said, “This visit is critically important to the Secretary and to the mission of the Department, and the kind of robust community engagement desired would not be possible given health and safety concerns throughout the regions.” But an Interior Department spokesperson previously declined to say whether Haaland would visit Allakaket or meet with critics of the Ambler Road project.

Silence won’t remain an option for long.

The Department of Justice will have to file briefs in the legal challenges brought by the chief’s conference and the environmental groups by November 12. The Biden administration has a choice. It will have to defend the Trump administration’s handling of the Ambler environmental impact statement, or it will have to take a different path, one with consequences that could undermine its legislative agenda.

Design and project management: Erin Aulov

Development: Beatrice Jin

Editors: Sasha Belenky, Bill Duryea, Andrew McGill, Lily Mihalik

Maps: Patterson Clark

Photo editor: Katie Ellsworth