Near the banks of the North Thompson River in British Columbia, about 400 miles northeast of Vancouver, the Tiny House Warriors village announces itself with a hand-painted sign attached to wooden stakes: “Unceded Secwepemc Territory.” The area is quiet and remote, with tall stands of spruce and cedar forming part of the world’s largest inland temperate rainforest. At the entrance to the village, a pile of logs creates a makeshift barricade. Beyond it, a cluster of five small wood-framed homes sit on trailers, their walls decorated with colorful murals depicting elements of the Secwepemc people’s history and culture.

About half a dozen people live in the village, but those numbers are frequently swelled by visitors, and in mid-December, the site was bustling with activity. Flora Sampson, a tribal elder, gave lessons on the Secwepemc language to camp participants, together with her granddaughter. Others performed songs on deerskin drums and told stories about the recent history of Secwepemc land struggles. Earlier in the year, residents made daily trips to the nearby river to honor and celebrate the thrashing, silvery salmon and trout migrating upstream.

“Like my grandpa George says, our culture flows from the land, our language flows from the land,” said Kanahus Manuel, who together with her twin sister Mayuk founded the Tiny House Warriors village in 2017. “When we resist and stand up and fight back, we’re saving ourselves from extinction.”

Kanahus and Mayuk Manuel stand near the Red Bridge in Kamloops, B.C. In September, Mayuk was injured and later arrested following a scuffle between protestors and Trans Mountain Pipeline security personnel in Blue River. Image: Aaron Hemens/HuffPost

As much as the Tiny House Warriors village has been a hub for maintaining Indigenous culture, it has also been a hub of resistance. The homes sit on a road alongside a construction site related to a massive expansion of the federally owned Trans Mountain Pipeline, a 1,150-km (710-mile) pipeline that carries 300,000 barrels of tar sands diluted bitumen every day from Alberta through British Columbia to an endpoint on the Canadian coast outside Vancouver. First proposed by the energy company Kinder Morgan in 2013, the expansion project would place a new pipeline alongside the existing one, almost tripling the system’s total capacity to 890,000 barrels per day.

Canadian officials are relying on the project to move the country closer to its goal of becoming a global “energy superpower,” as then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper pledged in 2006. At the center of his plan was the development of Alberta’s tar sands, enormous underground reserves of sand, clay, and oil spanning an area approximately the size of Florida. In the following years, energy companies proposed a series of new pipelines across Canada and the United States to deliver the high carbon-emitting oil from the tar sands to refineries and markets abroad, including the Trans Mountain expansion, Keystone XL, Northern Gateway, Energy East, and Enbridge Line 3.

Today, roughly 3.5 million barrels of tar sands are mined daily, nearly all of it shipped to U.S. refineries. Opponents of tar sands development, however, view it as a fulcrum for the rapidly accelerating climate crisis. The Northern Gateway and Energy East pipelines were canceled in 2016 and 2017 in the face of protests, and the Biden administration revoked the construction permit for Keystone XL last year. Construction of Line 3 was finally completed in September 2021, after overcoming a large opposition movement that saw over 900 arrests in protests across Minnesota.

Construction of the Trans Mountain Pipeline runs through a residential area in Vavenby, B.C. The construction of the path is part of a massive expansion route of the federally-owned pipeline.

Image: Aaron Hemens/HuffPost

For now, the Trans Mountain expansion is the only major tar sands pipeline battle currently at hand. The Canadian government has gone to extraordinary lengths to ensure its completion. “Right now, we’re prisoners to the American market,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in 2019 when announcing the project’s approval. Construction of the expanded pipeline began later that year, and the government hopes it will be up and running by fall 2023.

But the project has run up against determined opposition from First Nations groups and environmentalists, as well as municipalities, student groups, and some labor groups and politicians. Since the project’s proposal in 2013, protesters have staged dozens of actions to block construction along the pipeline’s route, resulting in over 300 arrests. Well over a dozen legal challenges have been mounted since the project was first announced, including by numerous First Nations, like the Tsleil-Waututh Nation.

The Tiny House Warriors village has been a prominent flashpoint in the conflict. Nearly half of the pipeline expansion’s proposed route lies within the territory of the Secwepemc Nation, which, like nearly all First Nations in British Columbia, has never relinquished its land to the Canadian government by treaty, land sale, or surrender. Secwepemc opponents of the project have argued that its construction violates their right to govern their own territory. By establishing a small village in the project’s path, the Tiny House Warriors have staked claim to land they argue belongs to their people.

In recent years, the Canadian government has been working to acknowledge its legacy of colonialism and heal its relationship with Indigenous people. However, the government and pipeline companies have fiercely opposed Indigenous land claims in court. In particular, they’ve used court-ordered injunctions to force First Nations peoples off their land through police enforcement, according to researchers at the Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations-led think tank at Ryerson University. These injunctions, which can prevent protesters from blocking pipeline construction and other commercial activities such as logging and mining, have enabled the government and energy companies to make an end run around Indigenous land claims. This dynamic is playing out vividly at the Tiny House Warriors village.

“Basically everything about the legal system is skewed against Native people,” said Pam Palmater, an Indigenous Mi’kmaq lawyer, Ryerson University professor, and activist. “Federal and provincial governments and even corporations use the justice system, they weaponize it against First Nations, land defenders, Indigenous people in a multitude of ways.”

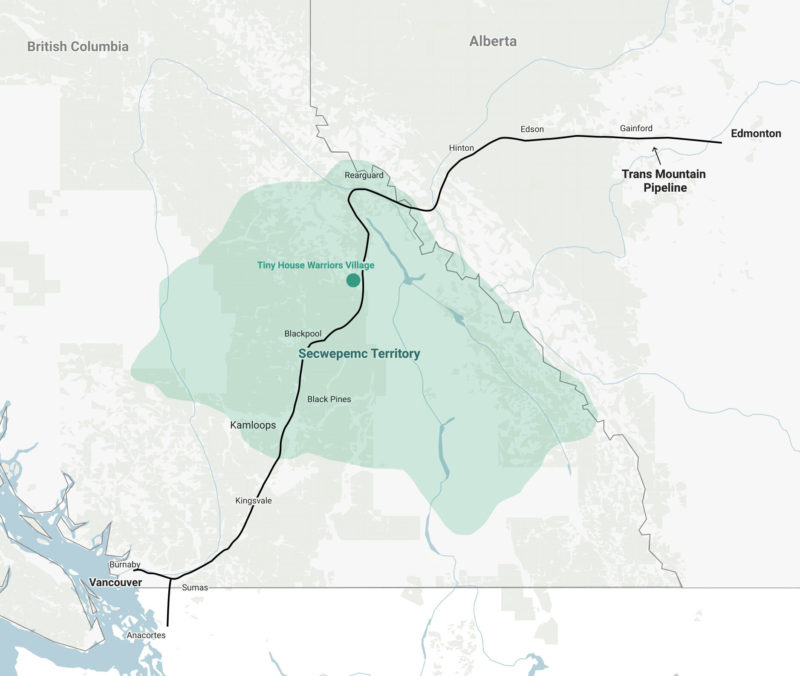

The pipeline route runs through through Secwepemc Territory.

Image: HuffPost

The Tiny House Warriors village was first established in 2017, after a traditional Secwepemc assembly declared its opposition to the Trans Mountain expansion, arguing that the project posed a threat to the local ecology and their land. But there are other motivations as well. Village inhabitants say the impending influx of construction workers to the site will pose a safety risk to women in the area; a 2019 report by Canada’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls found “substantial evidence” that temporary worker camps increase violence against women in nearby communities.

Tensions have risen steadily in recent years. In 2017, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the country’s federal law enforcement agency, formed a special unit called the Community-Industry Response Group to address issues of crime, national security, and public disorder surrounding energy projects in British Columbia — including protests in opposition to Trans Mountain and the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which is being built in a separate part of the province and is being blockaded by the Wet’suwet’en people and their supporters. In October 2019, a C-IRG officer fractured Kanahus Manuel’s wrist, she said, while arresting her on an access road about 37 miles north of the Tiny House Warriors village on charges of intimidation and mischief. An RCMP spokesperson said that following her arrest, Manuel was assessed at the local hospital and taken to a larger hospital, and that no evidence of a broken wrist had been provided to police. The spokesperson also said that a broken bone would trigger an investigation by the Independent Investigations Office of British Columbia, a civilian-led police oversight agency, and that no such investigation was launched. Manuel and a fellow protester were later acquitted of all charges in connection with the incident, and Manuel has filed a federal lawsuit seeking damages. The RCMP spokesperson declined to comment on the lawsuit.

The conflict intensified in July 2021 when workers began preparing a swath of forest to make way for a camp that would house up to 550 pipeline personnel for the duration of the Trans Mountain expansion’s construction. As part of that, the workers set up fencing near the Tiny House Warriors village and installed a high-tech surveillance system with cameras that appear to be monitoring the tiny homes, according to civil liberties advocates who visited the site.

“This is an area where we walked down to the river for more than three years to offer prayers,” Mayuk Manuel said. “And then they go and clear-cut the area and put us under 24-hour surveillance.”

In September 2021, several members of the Tiny House Warriors attempted to create a blockade using a large red cloth to stall semi-trucks hauling logs from the worker camp. On the following day, a security guard contracted by Trans Mountain tackled an unidentified Indigenous woman as she approached a security communications post at the construction site, sparking a melee between the protesters and pipeline security personnel. Videos of the incident obtained by Type Investigations and HuffPost show that in the ensuing scuffle, a security guard forcefully pinned Mayuk Manuel to the ground with his knee. Following a further struggle, she and the other protesters were able to escape.

Members of the Tiny House Warriors display red dresses and cloth to honor missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls along the perimeter of a camp that houses 550 Trans Mountain Pipeline workers in Blue River, B.C. Image: Aaron Hemens/HuffPost

Police later arrested five Indigenous protesters, including Mayuk Manuel, in connection with the incident. The British Columbia crown counsel charged them with varying combinations of assault, assault causing bodily harm, mischief, and other charges. No pipeline workers were arrested or charged in connection with the incident.

A Trans Mountain spokesperson said the company “respects the right to peaceful, lawful expressions of opinions,” and that it is “committed to ensuring our workforce demonstrates our core values of safety, integrity, and respect.” However, according to the spokesperson, the protesters had initiated the conflict by breaking through fencing, throwing rocks and debris at workers, and damaging equipment, thereby jeopardizing the safety of workers. “The events of September 15, 2021, were not activities of peaceful protestors but were premeditated attempts to stop work and damage equipment,” the spokesperson said.

Trans Mountain says it “strives to be a good neighbor” and ensure that its workers are courteous and respectful to local communities during construction. The Tiny House Warriors, however, view the presence of pipeline personnel at the site as a provocation.

“Our direct action happened in self-defense,” Kanahus Manuel said. “This entire situation illustrates exactly why we created our tiny homes village to begin with — to protect against the violence the Canadian government is bringing on our people here, especially our women and two-spirit people.”

The Tiny House Warriors village is located beside a camp that houses 550 Trans Mountain Pipeline workers. Image: Aaron Hemens/HuffPost

The Tiny House Warriors’ struggle stems from a two-pronged effort by Indigenous people in Canada to assert authority over their land in recent decades — by strengthening their stature within the country’s legal and political systems, but also outside of them, based on Indigenous values and systems. On the first front, First Nations won rights and protections under the Canadian constitution in the early 1980s, after which many groups began pursuing aggressive legal campaigns to assert sovereign rights and title over their traditional territories.

In a seminal 1997 case, the Canadian supreme court affirmed Indigenous groups’ right to claim use and occupation of their land if they could prove they had occupied it before the “assertion of Crown sovereignty,” among other criteria. Another major decision came in 2014 when the supreme court sided with the Tsilhqot’in people over British Columbia after the provincial government granted a commercial logging license on traditional Tsilhqot’in land, further establishing Indigenous ownership of land in British Columbia that First Nations people had not given up via treaty.

Indigenous groups have used these precedents to mount challenges to similar projects across Canada. In the case of the Trans Mountain expansion, First Nations groups including the Secwepemc have filed a number of legal challenges, arguing that the Canadian government failed to properly consult First Nations and infringed on their land titles when it approved the project. One of these lawsuits, brought by the Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh and Coldwater First Nations, significantly delayed the start of Trans Mountain’s construction, though the project was ultimately allowed to move forward. Meanwhile, court-ordered injunctions have enabled corporations and the Canadian government to combat on-the-ground resistance to projects like the Trans Mountain expansion, allowing construction and resource extraction to continue while larger legal questions of Aboriginal land title wind their way through the court system.

In 2014, a court granted Kinder Morgan’s application for an injunction covering the Trans Mountain expansion. The company had argued that the protests surrounding the project threatened to cause delays and uncertainty, costing the company millions of dollars in revenue. In 2018, the supreme court of British Columbia agreed to grant a new, province-wide injunction forbidding anyone from obstructing or impeding work on the Trans Mountain project and empowering police to arrest anyone who comes within 5 meters (about 16 feet) of the work site. Most people who are found guilty of violating the injunction are subject to seven to 28 days in jail, though in one recent case, prosecutors are seeking up to 60 days of jail time for someone who was convicted of violating the injunction.

Image: Aaron Hemens/HuffPost

Even so, Kinder Morgan moved to cancel the project that year, citing opposition to the project from British Columbia’s provincial government, though Indigenous critics of the project say their own opposition played a central part as well. But Trudeau swept in to buy the project for $3.5 billion ($4.5 billion Canadian) in an effort to keep it alive.

Miriam Galipeau, a spokesperson for Natural Resources Canada, said the Canadian government considered the environmental, social, and economic impacts the Trans Mountain expansion project would have, including the impact to Indigenous rights and interests, and ultimately determined the project was in the public interest. “Indigenous communities have diverse views about natural resource development in their territories,” Galipeau said. “We respect those diverse views, as well as the right of all people to voice those views in a safe, responsible and lawful way. We are committed to maintaining strong and enduring relationships with Indigenous communities through ongoing dialogue, established relationships and helping communities navigate matters related to accommodation measures, or any other project-related issues.”

“No relationship is more important to the government than the one with Indigenous peoples,” Galipeau said. “We recognize that some Indigenous peoples are in support of this project, while others are opposed.”

The Trans Mountain spokesperson said the pipeline expansion project has involved “unprecedented levels of involvement, and shared decision making, with Indigenous peoples and communities,” which have led to route changes, new construction techniques, and economic opportunities for local communities. “Through job creation, procurement opportunities, partnerships, and involvement in the environmental management and oversight process, long-term legacy and economic benefits for Indigenous peoples are being created,” the spokesperson said.

Indeed, opposition to the project is not uniform among Indigenous people. Some First Nations-led groups are making a play to purchase an equity stake in the pipeline. Meanwhile, according to Trans Mountain, as of November 2021, 67 Indigenous communities along the pipeline route have signed mutual benefit agreements with the company worth $580 million; those agreements often include financial compensation, job training programs, and a role in contract procurement. Simpcw Resources Group, a construction company owned by a Secwepemc band, the Simpcw First Nation, for instance, partnered with construction firm ATCO Structures to operate three pipeline worker camps in interior British Columbia — including the camp that has been contested by the Tiny House Warriors.

Nicole Plato, a spokesperson for the Simpcw Resources Group, shared a 2020 joint statement from Simpcw Chief Shelly Loring and Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Chief Rosanne Casimir in which they expressed their support for the Trans Mountain expansion project and called on the Tiny House Warriors to end their protest. “By providing opportunities for our people, we will continue to strengthen our economy in a way that still respects and honors the importance of Mother Earth for future generations,” Loring said in the statement.

But some Indigenous leaders who have signed such agreements have publicly insisted that the agreements do not necessarily mean they support the pipeline project. A few have noted that the economic poverty that afflicts native communities makes these deals difficult to pass up, while others have expressed a sense of the project’s inevitability, Vice News reported.

However, it is often economic interests, rather than concerns over the environment or land rights, that ultimately win out. One reason injunctions have been so effective in combating Indigenous land claims is that judges base their decisions, in part, on the extent to which each party will be impacted if the project moves ahead — a legal test known as the “balance of convenience.” In a precedent-setting 2004 case, a judge wrote in an opinion that the balance of convenience “tips the scales in favor of protecting jobs and government revenues, with the result that Aboriginal interests tend to ‘lose’ outright pending a final determination of the issue, instead of being balanced appropriately against conflicting concerns.” By and large, courts have viewed energy projects’ potential economic losses as a greater harm than the potential violation of Indigenous rights.

Even though Indigenous groups can also apply for injunctions, those efforts have seldom been successful in recent decades. Despite the increasing recognition of Indigenous rights in the courts, judges have granted Indigenous applications for injunctions against corporations only 19%of the time, according to a review of over 100 injunction cases since 1974 from a 2019 report by the Yellowhead Institute. By contrast, an updated August 2020 count shows that courts have granted injunctions against Indigenous people sought by companies and governments 81% and 90% of the time, respectively. The Yellowhead Institute’s research shows that corporations are filing injunctions with increasing frequency.

“When considering the injunctions brought before them by resource companies, courts tend not to pay any heed to constitutionally-protected Indigenous land claims,” said Shiri Pasternak, an assistant professor of criminology at Ryerson University and one of the report’s co-authors.

These injunctions can often include orders to authorize police enforcement of their terms, leading law enforcement officials to arrest pipeline protesters who violate the court orders. In the past two years alone, police have carried out major operations against a number of Indigenous protest groups, including Haudenosaunee people in Caledonia, Ontario, and Gitxsan people in northern British Columbia, for violating injunctions. Police have disrupted a Wet’suwet’en blockade of the Coastal GasLink pipeline three times since January 2019 — most recently in November 2021. “The incident you are referencing was the RCMP enforcing the Supreme Court injunction, as required by law,” the RCMP spokesperson said in response to a question about these operations. “Enforcing these injunctions are not optional for the RCMP, nor can we delay them indefinitely.” In deciding to grant Coastal GasLink’s requests for injunctions against the Wet’suwet’en people, the judge found that because stopping the pipeline would result in a “loss of employment opportunities” and a loss of tax revenue and economic growth, it passed the balance of convenience test.

Molly Wickham (Sleydo’), a Wet’suwet’en opponent of the Coastal GasLink project, said injunctions have become a cudgel that police, energy companies, and Canadian officials have been able to use to force Indigenous people off their rightful land. “[Injunctions] are being used as a tool to eradicate and diminish our rights as Indigenous people and our laws that we are upholding. And as a result, we’re spending time in jail or having to be dragged through this court process that’s costing thousands and thousands of dollars,” she said.

Construction of the Trans Mountain Pipeline runs through in a neighborhood in Vavenby, B.C. Image: Aaron Hemens/HuffPost

The consequences of the conflict over the Trans Mountain pipeline go beyond Indigenous land rights. Environmental experts have long warned that expanding production of the tar sands will lock in further increases in global temperatures, increasing the frequency of extreme weather events at a time when climate change is already wreaking devastation on ecosystems and human societies throughout the globe.

British Columbia has been particularly hard hit by extreme weather. Last summer, a “heat dome” caused over 500 heat-related deaths and untold numbers of animals to perish across the province. Then, in November, ferocious storms caused flooding and mudslides across the region, with the costs to repair the damage making it the most expensive climate disaster in British Columbia’s history, according to the Insurance Bureau of Canada. Along the route of the Trans Mountain expansion, construction sites and equipment stockpiles were buried by the November landslides, causing massive delays.

In April last year, Trudeau pledged to reduce the country’s carbon emissions by 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030, and Canadian officials say the country is still on track to meet its climate goals. Natural Resources Canada said the revenues generated from the Trans Mountain expansion project will be used to fund Canada’s clean energy transition. “Canada is committed to achieving net-zero by 2050,” said Galipeau, the Natural Resources Canada spokesperson. “Our government has committed to capping emissions from Canada’s oil and gas sector in a way that is compatible with our climate objectives.” But Trans Mountain opponents say the government’s support for the pipeline expansion flies in the face of its environmental commitments.

“Someday I’m going to have a hard time explaining to a young person that as climate disasters, wildfires, and heat waves, and landslides and floods raged literally all along the route of this pipeline, a prime minister who claimed to be a climate champion continued to try building a pipeline that would enable a major expansion of this country’s most polluting industry,” said Peter McCartney, a climate campaigner for the Vancouver-based Wilderness Committee, which opposes the project.

Climate-induced setbacks, combined with regulatory delays and on-the-ground opposition, including by the Tiny House Warriors, have continued to delay construction of the Trans Mountain expansion and caused its estimated cost to balloon to $16.8 billion ($21.4 billion Canadian) — nearly triple the project’s 2017 estimated price tag of $7.4 billion Canadian. In February 2022, the Trudeau administration announced that it would not provide additional public funding to the project. Instead, it has pledged to secure remaining funds from public debt markets or financial institutions, with a goal of placing the pipeline in operation by fall 2023. According to Politico, however, Trudeau’s cabinet recently approved a $10 billion Canadian loan guarantee for the pipeline after it secured funding from a group of unnamed Canadian financial institutions — though the Department of Finance argued that the move does not reflect new public spending. The worker camp near the Blue River is now open, according to Trans Mountain.

Kanahus Manuel, a member of the Tiny House Warriors, sits in front of a tiny home located in the Tiny House Warriors village in Blue River, B.C. Image: Aaron Hemens/HuffPost

For now, residents of the Tiny House Warriors village will continue to resist, despite the injunction. Others are doing so as well. Farther downstream from the Tiny House Warriors encampment, where the Fraser River meets the Pacific Ocean and where the Trans Mountain pipeline sends oil out for export, the Tsleil-Waututh Nation and other Indigenous peoples and environmental groups have also been rallying in opposition to the project and pressuring the insurance companies underwriting it — including Liberty Mutual and AIG — to cut ties. So far, 18 major international insurance companies have either chosen to rule out insuring the project or are unable to do so because of their policies.

Opponents also plan to continue using blockades and other nonviolent direct actions to slow down the project in hopes of ultimately forcing its cancellation. By standing in the way of the Trans Mountain project, the Tiny House Warriors and other Indigenous groups are following in the footsteps of similar pipeline protest movements across North America. And with the demise of Northern Gateway, Energy East, and Keystone XL in recent years, political momentum seems to be shifting to their side. If the Canadian government similarly decides to throw in the towel on Trans Mountain, it would be a hugely consequential victory for environmentalists, as well as for Indigenous people for whom this conflict is part of a longer-term struggle for self-determination over their ancestral land.

“Every day, we are striving to become independent, strong, thriving Indigenous nations,” Kanahus Manuel said. “The power that Indigenous people have is often found in being on the ground, in being out on our land — and that also happens to be the biggest threat to this pipeline.”