THE TRUMP FAMILY IS HARDLY KNOWN for its humanitarian impulses, but for a moment Donald Trump Jr. seemed like an exception. Back in 2010, Trump Jr. and his business partners made a surprising vow to build millions of units of prefabricated low-cost housing for some of the world’s poorest families and ship them to countries across the globe. The company also had what it marketed as a seemingly miraculous solution for helping to power the homes: Along with the housing kits, it would distribute small energy-producing wind turbines that could be affixed to their roofs.

What happened next offers a glimpse into how Don Jr. does business, a topic The New Republic and Type Investigations first investigated for a story last September. We wanted to learn more about former President Trump’s oldest child, who has become a hero to the Big Lie crowd. In that piece, we showed what happened when Don. Jr. and his partners promised to renovate a former naval hospital and to bring a Trump five-star hotel to the town of North Charleston, South Carolina. They left the hospital in a state of disrepair. The hotel was never built. The episode cost taxpayers at least $33 million, and Junior and his partners walked away with a profit. An electrician who witnessed rampant copper stripping told me the fiasco was at times like a “real-life Sopranos episode.”

But the reason Don Jr. and his partners were in North Charleston in the first place was to launch their housing venture, mass-producing and selling the prefabricated homes.

Business plans for the company, newly obtained in the course of our investigation, include Donald Trump Jr.’s photograph and financial projections that indicated hundreds of thousands of homes would be built, creating billions of dollars in revenue. In reality, all we were able to find are a few properties that the company built, including one for the mayor of North Charleston, South Carolina, a major booster of the company, and a handful of kits the company sent abroad.

In the process, they left investors high and dry and sued creditors rather than pay them what they were owed. The company made questionable promises about wind energy turbines, claimed giant losses on its tax returns, damaged a small law firm by failing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal bills, and refused to pay a temporary employment agency for workers the company provided.

Ultimately, one burned customer told us, Don Jr. resembled more “a three-card monte dealer” than a benevolent son of a billionaire trying to make his mark.

“Millions of Houses”

To create the low-income housing they envisioned, Don Jr. and his principal partner—longtime friend Jeremy Blackburn—needed a factory that could produce the parts. They found it in South Carolina. The 158,000-square-foot facility was formerly used to produce housing panels and came stocked with manufacturing equipment made by the Austrian company EVG.

There was a third partner in the business, Lee Eickmeyer, a Washington state farmer, who put in a nearly million-dollar investment and later claimed, in court documents, that he was taken advantage of in a conspiracy to deprive him of his money.

The company’s bold mission captured the attention of a wide range of people, including international officials and Wall Street veterans. “Anyone can have an idea,” says Christopher Jannou, an American expat small-hotel developer living in Zambia, who briefly worked with Trump Jr. in 2010. “What set these guys apart was that equipment. It’s very real and respected.” The EVG equipment pumped out 3-D panels that featured a foam core between wire mesh frames. Once they’re installed, concrete is blown into the panels, hardening them. The technology dates back decades and has applications from mining structures to highway sound barriers. In recent years, fire-resistant 3-D panel construction has become a small but growing part of the housing construction market.

Jannou said he met Don Jr. at Trump Tower in 2010 when Don Jr. was seeking a local American partner in Zambia for his newly formed company, Titan Atlas Manufacturing. Jannou was impressed at first. Don Jr. can come across as “very charming,” he told me. He remembered Junior pointing to the stunning view from his Trump Tower office. “Don said, ‘My dad has built all these beautiful skyscrapers and these gorgeous buildings. I can’t compete with that. But what I can do is go build millions of houses for the poor in the world,’” Jannou recalled.

“[Don Jr.] was desperate to make money on his own. And desperate people do stupid things.”

Jannou’s recollection dovetails with that of former Trump Organization fixer turned whistleblower Michael Cohen, who ultimately became embroiled in assisting Don Jr. with legal issues related to Titan Atlas Manufacturing. “You know why he ended up getting into this business?” Cohen said in an interview. “Because he wanted to be his own man. He didn’t want to be under the auspices or control of his father for his whole life. He wanted to make money on his own. He was desperate to make money on his own. And desperate people do stupid things.”

In 2010, Trump Jr. and Blackburn, who was also Trump Jr.’s partner in the failed naval hospital venture, had just purchased the factory. The two men bought the building and machinery inside it, along with more than 10 acres of land, from Charleston businessman Franz Meier for $4 million in 2010. Meier financed $1 million of the purchase price. Rather than work through banks, Meier accepted a roughly $10,000 monthly payment schedule over 10 years. But after two payments, the checks stopped coming, according to court documents.

Jeremy Blackburn, Don Jr.’s former business partner. Image: Joe Rubin

Meier sued in Charleston and won a default judgment. But Trump Organization lawyer Alan Garten countersued in New York state on behalf of Titan Atlas Manufacturing, claiming that Meier hadn’t properly disclosed patent issues with his panel equipment. The South Carolina judge said that Meier couldn’t collect until the New York case was decided. We asked Garten about his involvement in the case and sent questions for Donald Trump Jr. but did not receive a response.

Even as things got tense, Meier asked the younger Trump to wish his father a happy birthday. Meier tried to work things out with Trump Jr., emailing him and pleading that they settle their differences. “All this means is further time delay and legal expense,” Meier wrote. Trump Jr. responded that “you should rely on your counsel, as will we. The indemnity claim [for the patent issues] is going to wipe out the value of the property and the deficiency.” In other words, You are no match for our deep pockets. The looming New York case appears to have forced Meier into a settlement that multiple sources told us was for far less than was owed.

Meier told me that he didn’t want to discuss the painful chapter. “I have no interest in discussing my past with the Trump Organization. I have suffered the consequences of my relationship, put it behind me, and moved on with my life. I believe there is sufficient public knowledge about the machinations and business dealings of the [former] President and his family for you to write about whatever subject matter you want to illuminate,” Meier said in his email.

A Box of “Garbage”

Carlos Perez, a Bronx-based businessman, was likewise impressed by Don Jr.’s involvement and seeming passion—at first. Perez was looking to become a social entrepreneur when he and a partner from a company called Tactic Homes with an address in Tunisia agreed to purchase 36,000 Titan Atlas housing kits (about $900 million worth), which he intended to ship to the Middle East. “Don Jr. didn’t know me from Adam; I was just this Dominican kid raised in Washington Heights. But he took an interest. That meant a lot,” Perez recalled. The deal was in a sense aspirational, since Tactic Homes didn’t have the capital to buy all those kits. Perez said that Trump Jr. and Blackburn urged the two partners to sign the ambitious contract anyway, reasoning that the agreement would help both parties raise money.

Tactic Homes wired about $115,000 to Titan Atlas for three housing kits; the company planned to have the homes built and to use them as models to get financing from sovereign wealth funds—seeking good P.R. following the Arab Spring protests—to order thousands more. But when the shipping container arrived, Perez’s French-Tunisian partner wrote to Blackburn and Don Jr. complaining that the container was filled with “garbage,” adding in another email that there were “no windows, no doors, no cabinets, no plumbing, no electrical, no cables, no reinforcing bars.” Even after phone calls and visits to Trump Tower by Perez, emails that I later obtained show Trump Jr. refusing to budge, calling the allegations “nonsense” in a later email to Perez. In reality, the Tunisia shipment was one of multiple instances where the shipments ran into problems.

The TAM kit as seen in a business plan. The company promised to revolutionize affordable housing around the world, but left behind debt and unpaid taxes. Image: From the Titan Atlas Manufacturing business plan

Perez met with Junior one final time at Trump Tower still hoping for some kind of refund. “I looked up to the guy,” he said. “And I thought maybe face to face Don would see it was crazy not to give us back the money.” But instead, Trump Jr. told him something that he says he will never forget. “Don said, ‘Look, Carlos, you know my father,’” Perez recalled. “‘If my father would have been dealing with this, he would have sued you guys a long time ago.’ I knew what that meant—if it would have been Dad, he wouldn’t have taken too kindly to a request for a refund.”

An Unwitting Participant

Bank executive Phillips Lee was an unwitting participant in Titan Atlas Manufacturing’s efforts to woo investors. The New York–based Lee worked for the French bank Société Générale, or SocGen, as it’s known on Wall Street, overseeing its export finance division. His specialty was arranging financing deals through EXIM, the federal government’s Export-Import Bank.

Lee says that a Titan Atlas associate told him that Titan Atlas had a commitment from the government of Nigeria worth hundreds of millions of dollars. At SocGen, Lee wrote to the Nigerian housing minister in September 2011 about a $298 million loan his bank was proposing to arrange for the Federal Ministry of Housing and Land to purchase housing units from Titan Atlas. He never heard back. Lee says he wrote similar letters to high-ranking public officials around the world who, he was told, were also interested in Titan’s product, including the president of Zambia.

No world leaders or governments responded to Lee’s letters. The bank executive started having his doubts. So Lee decided to travel to South Carolina to see the factory that Trump Jr. and Blackburn had purchased—in his words, to “kick the tires” of this company with such bold ambitions. “I wanted to make sure that there was a real company, that there was something there,” Lee recalls. He found the trip less than reassuring. “It was just very small scale,” he said. “It was a skeletal operation, not well built out. They had lots of spare room.”

Lee recalled discussing deals the company said were in the works. Of one deal in particular, “I said, ‘How big is this deal?’ And [the Titan Atlas associate] said, ‘It’s going to be 20,000 units,’” Lee recalled. “And I said, ‘What the hell is that?’ I took out a calculator and said, ‘That is a billion dollars. Excuse me, that ain’t going to happen. Instead of 20,000,’ I said, ‘think about something that is in the digestible range—500 units.’” Eventually, Lee says, his relationship with Titan Atlas fizzled out when none of its big projects came to fruition.

Problems at the Factory

Titan Atlas had other troubles. In 2011, the firm was sued by a temporary employment agency, Alternative Staffing, a company that provided workers for the factory. In a contract signed by Jeremy Blackburn’s father, Kimble Blackburn, who joined Titan Atlas that year, Alternative Staffing agreed to provide the company with a variety of workers. Titan Atlas paid the first four invoices in full and a fifth one in part. But after that, according to the lawsuit, the company failed to pay the subsequent 26 weeks, despite the Trump family’s supposed solidarity with small-business owners and the “forgotten Americans.”

Alternative Staffing owner Jan Cappellini told me the company strung her along with promises of payment. Later, in court documents, Titan Atlas claimed that it failed to pay because some of the workers had criminal records. Ironically enough, the Titan Atlas official who signed the contract, Kimble Blackburn, had his own criminal history. In 2003, he had pleaded guilty to 36 felony fraud counts and was sentenced to up to 15 years in prison. Sevier County Attorney Don Brown said at the time that the case would “undoubtedly be the largest fraud ever perpetrated on a public institution in the state of Utah.” (The charges were expunged from Blackburn’s criminal record in 2012.)

In the end, emails obtained by The New Republic and Type Investigations show that Trump Jr. was able to extract a settlement from Alternative Staffing of 12 cents on the dollar. In 2013, Trump Jr. wrote to his partners bragging that he had managed “to settle the 65,000 claim against us for 7500 payable in 3 monthly installments.”

Peddling “Cutting-Edge Technology”

Don Jr. also helped promote a product, the TAM Wind Turbine, which the company dubiously claimed was the “most efficient certified Wind Turbine on the Market.”

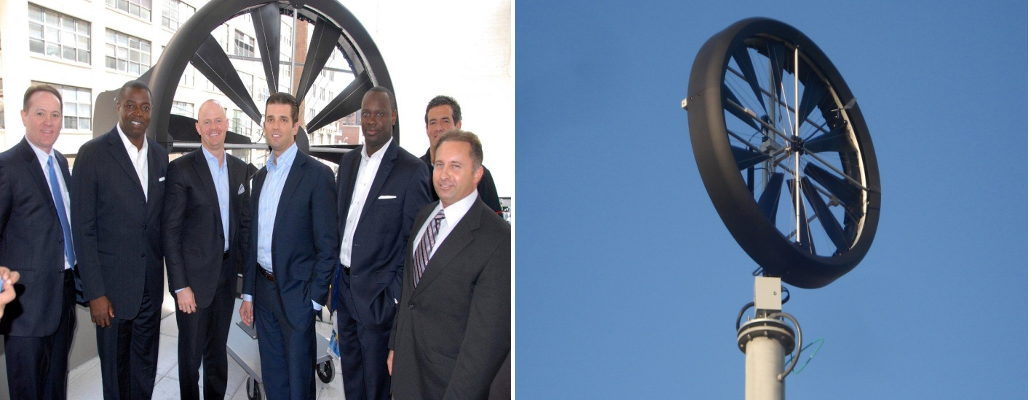

Business plans I obtained showed a photo of Donald Trump Jr. and Jeremy Blackburn on the roof of the Trump SoHo, smiling in front of one of the supposedly miraculous turbines.

Left: a photo that was distributed to potential investors of Donald Trump Jr. with Jeremy Blackburn on the roof of the Trump SoHo; right: the troubled wind turbine their company sold. Image: FROM THE TITAN ATLAS MANUFACTURING BUSINESS PLAN

One of the few customers who purchased a TAM housing kit told me that a few days after the housing kit arrived in Haiti in 2011, another crate showed up with a wind turbine, along with a COD invoice to pay thousands for what turned out to be a worthless item. The recipient, Jean Claude Assali, told me he was baffled because he never ordered the product. But he figured that it would help with frequent energy shortages following a devastating 2010 earthquake in Haiti. And because the Haitian small-businessman had also been promised he could be a sales rep for an exciting-sounding company led by billionaire Donald Trump’s son, Assali decided to pay up. But the turbine proved worthless, Assali said, describing it as impossible to put together and seemingly missing parts.

And the ground-floor opportunity to work for Donald Trump Jr. in Haiti was never to be. By 2012, Titan Atlas Manufacturing was mired in lawsuits and debts and ceased operating.

When I spoke with Assali over a crackly phone line from Port-au-Prince, he was still smarting from the loss. He asked me to let Donald Trump Jr. know there were no hard feelings against him or his father but that I should tell Don Jr. he’d like a refund.

Titan Atlas Manufacturing also benefited from an Obama-era federal stimulus program to sell five TAM wind turbines to the city of North Charleston. For a time, they were installed on the roof of City Hall. Titan Atlas had promised the city 50,000 kilowatts of power annually, enough to power 50 homes for a month. A letter from the company to the city’s federal grants administrator stated that “the turbine is patented and there are no other turbines similar in design or efficiency. There are no other known competitors or competing products for this application and use. We are the sole source for this product.” The purchase and the application for federal funds was signed by North Charleston’s longtime mayor, Keith Summey, who would go on to champion the naval hospital contract. At the time, Summey hyped the wind turbine project, telling the Charleston Post and Courier that “it’s part of that cutting-edge technology that we are trying to attract.”

But the turbines apparently never produced any measurably significant energy and were quietly torn down at the city’s expense in 2014, a few years after they were installed. Julie Elmore, an aide to Summey, wrote to the City Hall staff informing them of what had happened and what to say in case the media called. She wrote that she wanted to make sure staff were not “blindsided,” adding that the city didn’t want to “put any more money in them since we have no true way to measure its efficiency.”

Wind energy expert Paul Gipe told me that it’s no wonder TAM turbines barely worked, calling the design worse than junk science. Gipe added, “The original Windtronics design would be hard-pressed to run a 100 watt light bulb for an entire year.”

“The original Windtronics design would be hard-pressed to run a 100 watt light bulb for an entire year.”

In an interview with me in 2018, Blackburn did not dispute that the turbines did not work as promised but said that he and Don Jr. were not responsible because, in reality, Titan Atlas was simply rebranding another product. “Just like the local Ford Motor Company doesn’t make the Ford cars; they sell them,” Blackburn said. “We sold the wind turbines, and they were part of our kit for a vertically integrated [system to] supply your own power. So we sold the turbines, but we didn’t manufacture the turbines.” Blackburn’s statement appears to contradict promises Titan Atlas made in 2011 to the City of North Charleston, when the company told the Charleston Post and Courier that Titan would bring nearly 100 jobs manufacturing its turbine to its North Charleston plant. Additionally, a Titan Atlas investor presentation that we obtained claimed that the company was planning to expand to Mexico City with a “120,000 ft2 plant, 3 lines with support and wind turbine production.”

Tragedy Strikes

Despite his history of fraud, Kimble Blackburn became a key player at Titan Atlas after the tragic suicide by gunshot of the vice president of TAM Energy, Robert Torres, in June 2011. The elder Blackburn took over many of Torres’s duties, including becoming the city’s point of contact for Titan Atlas, after the wind turbine sale was completed and the contract with Alternative Staffing was signed.

At a Red Robin burger joint outside Atlanta, Torres’s son Scott shared with me his dad’s now vintage iPhone, which contained text messages related to his hire. The younger Torres told me his father, who served for several years in the Army, was excited when Don Jr. personally approved his hire as vice president of TAM Energy in late 2010, a claim the text messages corroborate.

When I interviewed Jeremy Blackburn in 2018 in the empty former Titan Atlas warehouse, he recalled the morning Torres died. “I was talking to him on the phone about 5:30 in the morning, and he didn’t show up for our 7 a.m. meeting, and so I went over to his house at 8:30, and they were wheeling him out,” Blackburn said. Scott Torres told me that when he showed up in North Charleston, Blackburn had arranged an impromptu memorial service for Torres. He said that Blackburn told him that his father may have been upset about problems at work, perhaps involving a major deal with China.

While it’s unclear exactly what the purported deal with China was about, our investigation found two contracts with potential values in the hundreds of millions of dollars. The earliest supposed blockbuster deal was a signed agreement from 2010 with a Mexican firm called KAFE.

The KAFE contract was hugely ambitious, stating that TAM would provide 43,614 TAM kits to be used by KAFE to build “military housing” for the government of Mexico, making the total value of the deal worth more than $500 million. According to Blackburn’s own account and sources in Mexico, Trump Jr. and Blackburn made at least one trip in 2010 to Sonora, Mexico, to meet with top government officials.

When I looked into KAFE, I discovered the company was so small that its office was above a furniture store in Mexico City. It was hard to find anyone with any knowledge of the company, but I did track down one former employee, a management official, who asked to remain anonymous but provided some details on the strange contract with Titan Atlas Manufacturing. Yes, his boss, Sergio Flores, had had multiple talks with Titan Atlas, but as far as he knew they never led to any TAM kits making their way to Mexico.

We found no evidence that any houses were ever built in Mexico with kits from Titan Atlas. Donald Trump Jr. did not respond to questions we sent to him through his lawyer regarding the deal. Potential investors and customers like Carlos Perez said they were told about this and other supposedly major deals as evidence of the company’s viability. The New York law firm Solomon Blum Heymann prepared the contract and did other work for Titan Atlas. The firm was described in a deposition by Blackburn in an unrelated matter as Titan Atlas’s “legal counsel.” But the firm was never paid $310,759 for work performed for Titan Atlas, according to Blackburn’s 2013 bankruptcy filing and a source close to the firm. The source told me that Don Jr. was personally involved and said the firm was “hoodwinked” by Don Jr. and Blackburn, adding that the company strung the law firm along with promises to pay “when projects came to fruition.”

A Red Flag

Solomon Blum Heymann was not the only law firm that Titan Atlas Manufacturing failed to pay. A Philadelphia law firm, Mendelsohn and Drucker, which represented the company in patent litigation, was awarded a more than $400,000 judgment, covering unpaid costs and interest, against Titan Atlas in a federal lawsuit. Multiple sources told me that Titan Atlas only paid $100,000 of that judgment, with the remainder still outstanding today. “The record in this case shows a history of dilatoriness,” wrote U.S. District Judge Michael Baylson in 2013. “Titan is a serial offender of the principle that corporations must be represented by counsel. Over the past 24 months, not one, but four law firms have had to withdraw from representing Titan due to Titan’s repeated failure to pay for the legal representation it received.”

Even as Titan shirked six-figure legal bills, Don Jr. may have benefited from unpaid debts. TNR obtained a copy of Don Jr.’s 2011 and 2012 Titan Atlas Manufacturing federal tax returns, which are filed through a form called a K-1. In 2011, the tax forms show Don Jr. was allocated $1,080,373 in losses. In 2012, he was allocated $439,119 in losses.

The returns raise a thorny question for Don Jr.: whether the former president’s eldest son ran up debts that were never paid and then claimed the debts as losses. To be clear, we do not know if the expenses on his tax return were unpaid. We asked Trump Jr. if he deducted expenses that had not been paid but did not receive a response.

The deductions call to mind what The New York Times reported in its seminal article about President Trump’s taxes, where it found Trump Sr. claimed huge and questionable losses in order to collect tax refunds as high as $72.9 million.

Trump Jr.’s Titan Atlas tax returns included $431,603 deducted in 2011 and $492,283 deducted in 2012 for what he called “professional expenses,” a category that includes legal and accounting costs, according to the IRS. The two years of deductions add up to over $923,000 for the claimed expenses.

A former business associate of Don Jr.’s told TNR they were skeptical about Don Jr.’s expense claims. Noting the multimillion Deutsche Bank loan, the source said, “It would be very difficult to imagine that the cost of the litigation would be almost one third [of the loan amount]. I don’t know—it seems awfully high.”

David Buckley, a tax lawyer I consulted, says the deductions could be problematic for a multitude of reasons, including the fact that as a principal in the company, Don Jr. would have been able to deduct the losses from his overall income in 2011 and 2012, netting him thousands of dollars. An important caveat, Buckley said, is that Don Jr. could have later amended his taxes to reflect the unpaid debts. But by the time Don Jr. filed his 2011 and 2012 taxes, the company was already being sued by multiple creditors, making Don Jr.’s potentially claimed expenses particularly dubious. “Why claim expenses you’ve shown no inclination to pay? That’s clearly a red flag,” Buckley said. Donald Trump Jr., contacted through his attorney Alan Garten, did not respond to questions on this matter.

Alleged Theft of Payroll Taxes

In 2017, The Washington Post reported that TAM had 18 federal and state tax liens totaling more than $100,000. But the Post did not elaborate on what those liens were for. It turns out that a majority of the owed taxes are related to a practice the company regularly engaged in, according to the tax liens on file, of deducting its employees’ federal and state taxes and Social Security payments but failing to turn them over to the IRS and the South Carolina Department of Revenue.

“In effect, Titan Atlas appears to have stolen from their own employees and the federal government,” Buckley said. The IRS and the Justice Department regularly prosecute taxpayer trust fund schemes. As a principal in the company, Don Jr., along with his other partners, would appear to be responsible for the debt and could be prosecuted, according to IRS and DOJ web pages that discourage the practice. “These taxes are called trust fund taxes because you actually hold the employee’s money in trust until you make a federal tax deposit in that amount,” the IRS states.

In a 2018 interview, Blackburn acknowledged some unpaid tax liens from the company he started with Don Jr. but said he bore no responsibility for Titan Atlas Manufacturing liens. The liens, Blackburn said, “were all for wages, for the final returns not being filed. The problem is I can’t file them, because I resigned from the company.”

“In effect, Titan Atlas appears to have stolen from their own employees and the federal government.”

The Trump Organization did not respond to several attempts to reach Donald Trump Jr. or Alan Garten. In an interview for a 2017 Washington Post story, Garten minimized Don Jr.’s role. “He was a passive investor, and he lost money,” Garten said. “I’m sure he wishes he didn’t do it. He viewed it as a start-up with every intention of succeeding. It just failed.” And yet Don Jr. was involved enough with Titan Atlas Manufacturing to hold sales meetings in Trump Tower and to lowball creditors.

A Doppelganger Company Emerges

By 2013, Titan Atlas Manufacturing had wound down its operations and, in its place, a new, seemingly identical company called Titan Atlas Global, based out of the same warehouse, sprang up. Titan Atlas Global had different leaders: Jeremy Blackburn was now CEO, and Don Jr. was no longer part of the ownership structure. But emails I obtained showed that Don Jr. continued to push sales of Titan Atlas Global’s core product, 3-D panels, well into 2013. And a person associated with Titan Atlas Global told me that Trump Jr. also earned money through rent payments he received from Titan Atlas Global for using the warehouse space.

Titan Atlas Global, it turned out, had a poor track record, like its forerunner, including failing to obtain legally required workers’ compensation insurance. That omission came into play when a worker at a disastrous, never-completed development of low-income homes in North Charleston had his arm mangled in a cement mixer in 2013, according to workers who were there. “It was horrible; blood was everywhere,” recalled one of the workers who accompanied the maimed man to the hospital. The state of South Carolina picked up the tab for the workers’ compensation and hospital bills and then filed a tax lien against the company for roughly $67,000, according to documents I exclusively obtained through a freedom of information request to the state of South Carolina.

Former Trump attorney Michael Cohen told TNR and Type Investigations that, in 2014, “Don Jr. came to me in tears, concerned that he’s going to end up destroying the relationship between the Trump Org. and Deutsche Bank and that his father was going to kill him. And so he asked me to intercede to speak to his father about buying this debt for three and a half million dollars.”

Michael Cohen arrives in Trump Tower, in New York, Friday, Dec. 16, 2016. Image: Richard Drew/AP Photo

“So I go into the office by myself, and I ask Donald for the three and a half million dollars to help Don with a situation. Mr. Trump gave me that inquisitive look and said, ‘What is going on? I need to know right now.’” Once Cohen told the future president the $3.5 million still owed on the Deutsche Bank loan was connected to Don Jr.’s affairs with Jeremy Blackburn, Cohen said, Trump Sr. exploded. “He told me, ‘I hate that guy. Don has the worst fucking judgment of anyone I’ve ever met.’”

Cohen said Don Sr. first refused to help. “He told me, ‘I’m not giving it to him.’ I said, ‘Mr. Trump, it’s with Deutsche Bank.’”

Cohen said that Don Sr. decided to purchase the Deutsche Bank loan because “Mr. Trump’s concern was that the default would damage the working relationship with Deutsche Bank. Also, it would be perceived by the press as his,” meaning Don Sr.’s default. Cohen said Trump also wanted to “extinguish Don Jr.’s personal guarantee.”

Neither Donald Trump Jr. nor Donald Trump Sr., reached through Garten, responded to requests for comment on Cohen’s account.

In 2011, the nearly $1 million that Lee Eickmeyer, the Washington state farmer, had loaned Titan Atlas helped guarantee the $3.65 million from Deutsche Bank, according to court documents. But his relationship with Trump Jr. turned sour after Donald Trump Sr. instructed Cohen and former Trump Organization CFO Allen Weisselberg (currently under indictment) to buy the loan from Deutsche Bank in 2014, as a morally questionable, but arguably legal, move to keep Eickmeyer and other creditors at bay.

In a court filing in 2015, Eickmeyer accused both Don Jr. and Don Sr. of having engaged “in a civil conspiracy to deprive Lee Eickmeyer of a million dollars.” The case was closed in 2016 with no admission of wrongdoing by Titan Atlas Manufacturing.

Michael Cohen says he still has affection for Don Jr., a guy he remembers as someone who “loves the outdoors” and “hates being inside an office.” But, Cohen told me, Don Jr. has clearly lost his way. “Don used to work very hard to ensure that he wasn’t like his father. Unfortunately, after this whole White House experience, I think he’s becoming exactly like his father. And sadly, if you look at some of these earlier issues, you’ll start to understand that he’s more like his father than he thought.”

This story was produced with support from the Wayne Barrett Project.