LITTLE ROCK, ARK. – It’s a scorching July day during the pandemic’s first summer. In the month since the murder of George Floyd, residents have gathered frequently in front of the Arkansas State Capitol, marching to protest the police killings of Black people across the country.

But today there’s something more confrontational on the horizon. About 20 anti-police-violence activists are preparing to “hold the line”—with homemade protest signs as their shields—as a group of Blue Lives Matter supporters barrel toward them. Brittany Dawn Jeffrey is among the demonstrators. Over the course of the summer, the 30-year-old activist has become a recognizable figure throughout the state, known for her relentless organizing and social media presence.

In a video captured by a reporter, six large men can be seen striding directly toward Jeffrey and her fellow activists, followed by dozens of others. Leading them is Richard Fought, a home insulation salesman, who is wearing a muscle shirt and holding a large Thin Blue Line flag. Pummeling their way through, Fought and the other men crash into Jeffrey’s group as police nearby stand and watch. Brawls break out. Fought would later brag on social media that he “smashed a couple” of activists, in one case with police assistance, though he later told us via text message that his violence was in self-defense. Some of the racial justice protesters were injured, according to a demonstrator who was there.

The Little Rock Police Department told us it never investigated Fought’s actions; there’s no evidence assaults by police supporters were ever investigated. Instead, police immediately confronted Jeffrey, part of a pattern that summer in which Black activists and their allies say they were singled out for surveillance and mistreatment.

Video from that day wound up being important for another reason: Authorities used it to build criminal cases against Jeffrey and others—kicking off a federal prosecution that would land her in jail, where she remains today.

The Nation and Type Investigations reviewed hundreds of law enforcement e-mails obtained through records requests. They show that police began monitoring Jeffrey and other protesters just days after Floyd’s murder, apparently for participating in peaceful demonstrations. This surveillance continued for months.

It’s not unusual for police to monitor and attend protests, but what’s troubling, notes Holly Dickson, the executive director of the ACLU of Arkansas, is the level of surveillance that Jeffrey and her fellow activists were subjected to. “Anytime we have seen this kind of overreaction by law enforcement officers” in Little Rock, “it’s in response to racial justice movements and gatherings organized by members of the Black community,” Dickson said.

As the protests escalated across the country, Jeffrey’s frustrations mounted—fueled in part by what she saw as harassment by police—and her actions grew more confrontational. In December 2020, five months after the incident at the State Capitol, Jeffrey was arrested for attending a nighttime attack where others threw homemade Molotov cocktails at empty police cars. There’s no evidence Jeffrey herself made or used incendiary devices, but she acknowledged planning to slash tires and break car windows with others.

Had Donald Trump not been president, Jeffrey might have escaped with comparatively lenient felony vandalism charges under Arkansas law. Instead she became a target of a historic federal crackdown that year against racial justice protesters and organizers. In building these cases, prosecutors throughout the country leaned on rarely used conspiracy charges to cast a wide net. In Jeffrey’s case, that meant a potential prison sentence of 30 years or more. She has been incarcerated since June 2021.

The national crackdown in 2020 was far from the first time the federal government has responded to Black liberation movements with repressive force to disrupt activist organizations before they gain momentum. But the cases in Little Rock are especially illustrative of this dynamic, which now spans two presidential administrations.

Nationwide, the 2020 racial justice protests resulted in at least 326 federal cases, according to Princess Masilungan, a staff attorney at Creating Law Enforcement Accountability & Responsibility (CLEAR) at the City University of New York School of Law. She is a coauthor of a report published by the Movement for Black Lives that documents the Trump administration’s broad crackdown on Black activists in 2020. Some of those activists are still incarcerated or awaiting trial.

“You can make very clear through lines between the uprisings of summer 2020 for racial justice and COINTELPRO in the 1950s and 1960s,” Masilungan told us, referring to the notorious FBI counterintelligence program against political movements. “In both instances, the federal government had the same goal, and that goal is disruption.” A key strategy of disruption includes “impairing the operational capabilities of the key threat actor,” she said.

In Little Rock, that meant Dawn Jeffrey.

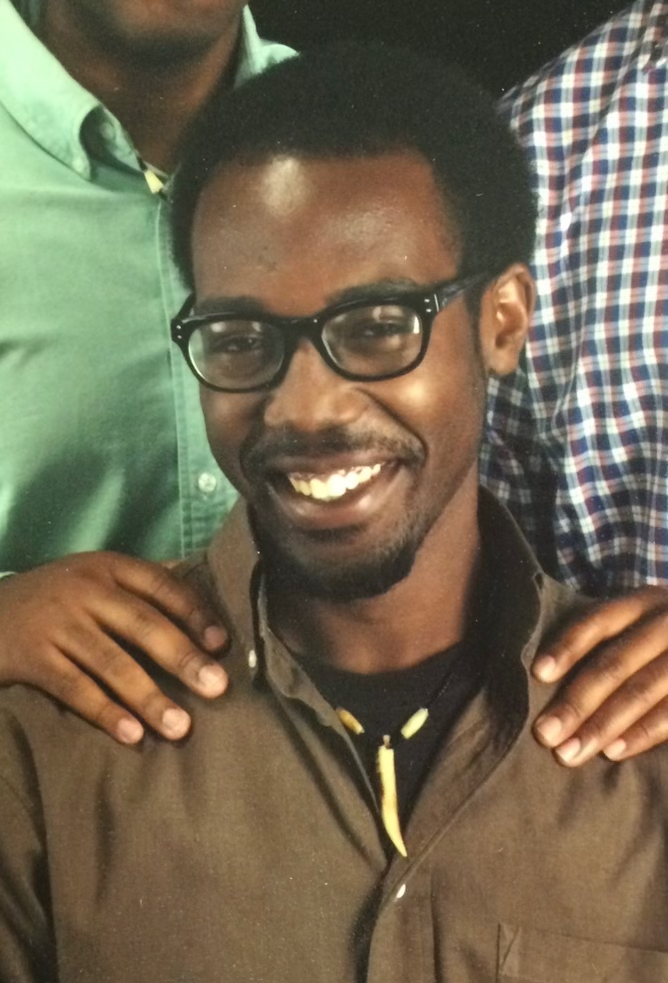

Supporters of activist Dawn Jeffrey are crowd-funding to support her legal fees. Image: Rumba Yambú/Intransitive

At t the time of George Floyd’s death, the Little Rock Police Department had already been accused of racist violence. In 2012, Officer Josh Hastings, who was known to have attended a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan, shot and killed 15-year-old Bobby Moore during an attempted car robbery. In February 2019, Officer Charles Starks killed Bradley Blackshire, 30, during a traffic stop. Hastings was fired and found civilly liable; Starks resigned. Both killings incited local outrage. Jeffrey and other activists saw them as part of a pattern.

Jeffrey had been involved in community work and political watchdogging for years. She said she attended her first protest after the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin, and friends paint a picture of a dedicated activist. An award she received in 2018 from a local lifestyle magazine honored her community outreach work empowering Black youth, homeless people, and others in need—values she said she learned from her mother.

“I’m just someone who cared about my community, an organizer who cared about what was going on with Black people—to me, ‘Black Lives Matter’ is a slogan, but I’m Black, and my life matters,” she told us from jail.

In early 2020, Jeffrey organized a campaign for a seat in the state legislature for her friend Ryan Davis, a prison reform activist and the executive director of UA Little Rock Children International, a partnership between the University of Arkansas and a nonprofit organization that serves families in the area. Davis lost by a single vote.

“There are folks who are very vocal about the fact that they think [Jeffrey] was too loud, that she was, in their words, doing too much,” Davis said. But “I don’t find anybody out here right now as intrepid as her, because she was such a powerful voice.”

In the weeks following Floyd’s murder, Jeffrey started a statewide bail fund for protesters. It’s now a permanent fund for people in Little Rock who can’t afford bail.

In a video promoting the fund, Jeffrey laid out her theory of change. “Protests disrupt daily lives as usual, so it’s good to start disrupting business as usual for them,” she says. “When you start taking it to them and put it in their face, where they can’t ignore it, then they start listening and say, ‘Well, what are they talking about?’”

Other Arkansas activists shared her approach. Demonstrations for racial justice in Little Rock were disruptive but peaceful. That soon changed. Police amped up their use of riot munitions. Protesters smashed the windows of downtown businesses late in the night, according to police incident reports sent to us in response to a records request.

Arkansas State Police began using a “fusion center,” a post-9/11 innovation that was meant to facilitate information sharing between local and federal police for anti-terrorism purposes, to track even peaceful protesters—endangering First Amendment rights to free speech and assembly. Records indicate that the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Arkansas State Police compiled lists of upcoming protest events, including some explicitly described as peaceful, echoing the War on Terror–era surveillance of Muslim gatherings.

“There was a concerted effort by law enforcement to do cross-agency cooperation and communication in response to these protests,” said the ACLU’s Dickson regarding the sharing of tips between the city police and state fusion center. “It was very clear it was happening, from [the use of] infiltrators to [carrying out] open and obvious surveillance.”

Apart from tracking Jeffrey, local police were following false leads, including an unsubstantiated rumor that busloads of antifa activists were booking hotels in the city. Federal and state police tracked protests across Arkansas, while US Attorney General Bill Barr activated all 56 of the nation’s FBI Joint Terrorism Task Forces, which rely on deputized local law enforcement, to stop “violent radical elements.”

In July, Barr traveled to Little Rock to meet with local law enforcement officials. In public remarks, he said the FBI’s terrorism task forces were working with local police to share intelligence “and go after the people we think are ringleaders” behind protest violence.

Protestors, including Dawn Jeffrey, at the Arkansas State Capitol on July 18, 2020. Image: Ebony Blevins

The Nation and Type Investigations, in partnership with the Arkansas Nonprofit News Network, sent public records requests to the Arkansas State Police and Little Rock Police Department for all documents related to protest activity, rioting activity, and the destruction of property in Little Rock from June through September 2020. The response included hundreds of pages of e-mail records between local police, state intelligence officers, and federal agents. Taken together, they show authorities zeroing in on Black activists, including Jeffrey, for protest activity—while largely dismissing the threat posed by counterprotesters.

In an e-mail dated May 30, 2020, Heath Helton, the assistant police chief in Little Rock, warned of an event “which to my understanding is being organized by Dawn Jeffrey…. Our partners at ASP [Arkansas State Police] and the State Capital have been made aware of this event, which is supposed to be peaceful.” A June 1 screenshot of Jeffrey’s Facebook page about a die-in—when protesters simulate being dead—also appears to have originated from the Arkansas fusion center.

The state police did not respond to questions we sent about Jeffrey. The Little Rock Police Department defended its approach. “As with any policing agency, the role of LRPD is to protect the citizens … they serve. Ms. Jeffrey had/has a public page which means it is viewable,” a spokesperson for the department said. “Therefore, there can be no violation in looking at a public page.”

“You can make very clear through lines between the uprisings of summer 2020 for racial justice and COINTELPRO in the 1950s and 1960s. In both instances, the federal government had the same goal, and that goal is disruption.”

Princess Masilungan, staff attorney at Creating Law Enforcement Accountability & Responsibility (CLEAR)

Jeffrey is by far the most mentioned activist in the law enforcement e-mails we reviewed. In one instance, surveillance records line up with an arrest. On July 12, she was arrested by local police at a demonstration outside of a custard shop in nearby Conway. A video recorded by a reporter shows police calling Jeffrey by name and then immediately handcuffing her without a clear reason. The Conway Police Department said she was arrested for trespassing. Intelligence officers for the Arkansas State Police were aware that Jeffrey would be at the event because they were monitoring her Facebook page in the fusion center and sent out an e-mail with a link to a livestream of the protest. While it’s not clear whether this monitoring led directly to her arrest that day, the e-mail was one of at least eight sent by senior intelligence officials in the fusion center that referred to Jeffrey’s organizing or her participation in nonviolent protests. By comparison, out of hundreds of e-mails and other communications, we saw few that referred to counterprotest groups—and even when they were mentioned, law enforcement focused not on the threat of violence they might pose but on possible violence initiated by racial justice protesters. In one e-mail, an FBI agent dismissed a man’s threats “encouraging the destruction of African Americans’ property” as “just talking online.”

The heavy surveillance of the protesters ultimately caught up with Jeffrey—thanks in part to a T-shirt.

One of her closest friends, Mujera Benjamin Lung’aho, was also at the July protest at the Capitol. The two first met in high school, where they played soccer together, and reconnected years later as the racial justice uprising in Ferguson, Mo., reverberated across the country. They eventually grew close enough that Jeffrey spoke at Lung’aho’s father’s funeral.

At the Capitol clash, Lung’aho had worn a distinctive shirt. According to a warrant later filed to search his phone, a detective claimed to have recognized Lung’aho’s shirt and other specific features from surveillance video taken a few days earlier during a vandalism spree at a local Confederate cemetery, where several people were caught on camera destroying monuments. Officers showed up at Lung’aho’s residence and arrested him after a foot chase. “Under the current climate, I just was compelled to flee,” Lung’aho recalled in a conversation with us.

When the police searched his phone, they found encrypted group chats and social media messages that they claim tied him to high-profile demonstrations in Little Rock throughout 2020. This turned out to be a key moment for law enforcement—and a big payoff after months of tracking Black activists.

According to the authorities, messages on Lung’aho’s phone indicated that he participated in several attacks on police vehicles. After arresting him, the police reached out to another alleged participant, Emily Terry, who’d messaged with Lung’aho the morning after the most recent outing. According to police documents, Terry positively identified others who were involved. Although a criminal complaint alleged that Terry threw a Molotov cocktail, Terry was never indicted. Terry declined to speak with us when reached by phone.

Center of the dragnet: BLM protester Mujera Benjamin Lung’aho faces criminal charges after being surveilled for months. Image: Michael Kaiser

On December 17, Jeffrey was arrested and charged. Federal prosecutors alleged that she was present when Molotov cocktails were made at her house and drove with friends who tried but failed to set an empty squad car on fire. Three other activists, Renea Goddard, Loba Espinosa-Villegas, and Emily Nowlin, were also arrested and agreed to plead guilty to lesser charges. In interviews, they said they were friends with Jeffrey and that her home had become a haven for activists that summer. None recalled her plotting illegal actions, and the police affidavit doesn’t identify her by name when describing the more serious incidents that night.

Espinosa-Villegas told us that it seemed, based on police questioning, that prosecutors saw Jeffrey and Lung’aho, the only Black defendants charged, as the “big fish.”

“Their intention was to try and figure out, was it [Jeffrey or Lung’aho] who was the leader?” The actual leader, Espinosa-Villegas said, was another person whom prosecutors accused of illegal actions, according to a criminal complaint naming multiple defendants. The documents also show that prosecutors named two others, including Terry, who allegedly committed similar crimes. None were indicted.

In repeated interviews, Jeffrey denied she had ever possessed or used a Molotov cocktail. Under immense pressure given the charges against her, and fearful of her chances at trial, she accepted a plea deal in May. In her plea agreement, Jeffrey acknowledged being present during the attack and the mixing of Molotov cocktails and “agreed with others to commit acts of vandalism on government buildings and damaging police cars by puncturing tires and/or breaking windows.”

“There’s no way you can be an American citizen feeling like you’re being attacked or at war with your own government,” she said in an interview. “When do the scales balance for justice?”

Jeffrey’s supporters present an image of a leader dispensing hard truths about political injustices in America, unfairly persecuted by the powerful entities she criticized. By contrast, those on the other side of the political spectrum see her as a provocateur who got what she deserved.

In a Facebook group called “Make Little Rock Great Again,” whose moderators have alluded to being local police officers, an administrator of the page posted a cartoon of a police officer shooting a Black woman in the head, mocking a post by Jeffrey. One person commented, “Be a shame if she came up missing,” and followed that with: “Lemme rephrase that correctly…replace she with it.” When asked about the page, a police department spokesperson said, “There’s no way to conclusively determine if this page is moderated by any member of the Little Rock Police Department.”

Lung’aho, a spoken-word artist, told us that he and Jeffrey had both been targeted for their politics. He’s accused of throwing Molotov cocktails on multiple occasions and faces more time in prison than anybody else. “The entire reason why we were doing the activism that we were involved in is because we were doing something for Black people,” Lung’aho said, speaking to us from jail.

“There’s no way you can be an American citizen feeling like you’re being attacked or at war with your own government. When do the scales balance for justice?”

dawn jeffrey

Not all of the jurisdictions that experienced unrest in the wake of George Floyd’s murder—even when that unrest turned destructive—resorted to federal prosecutions. Our past reporting found that such prosecutions were especially likely in jurisdictions whose US attorneys were politically affiliated with the Trump administration.

In Little Rock, Trump had an ideological ally in Cody Hiland, then the US attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas. A former local prosecutor—and, before that, deputy chief of staff to former governor Mike Huckabee—Hiland showed an eagerness to pursue the Trump administration’s political goals, once resurrecting an investigation into the Clinton Foundation. In Congress, GOP Senator Tom Cotton, who later called for federal troops to be deployed against racial justice protests, lauded Hiland’s nomination by Trump.

In an op-ed published amid the protests, Hiland wrote, “It is my prayer that the shrill cries of ‘Defund the Police’ always be muted by our nation’s earnest declaration that we ‘thank God for the Police.’”

When police found messages and photos on Lung’aho’s phone suggesting he was involved in the attacks, they sent the evidence to agents at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Hiland soon got personally involved in the case, inviting Lung’aho’s attorney, Michael Kaiser, to meet with him at the police station where Lung’aho was being detained.

The US attorney hoped that he could persuade Lung’aho to provide information about other protesters, according to Kaiser. Hiland told Kaiser he had the authority to add several charges involving the use of a destructive device in a crime of violence that would carry sentences of 30 years to life. “I hadn’t ever seen that before,” Kaiser said, adding that it was unusual for a US attorney to get so involved in a case that didn’t involve charges like murder or drug trafficking.

Prosecutors’ actions in the case align with findings from the Movement for Black Lives report. The authorities filed multiple and redundant charges against protesters, a technique critics say is meant to pressure defendants into accepting plea deals. The same technique was used by federal prosecutors against at least 84 racial justice protesters in 2020. One protester in Philadelphia was hit with four federal arson charges for burning two police cars, because the cars had benefited from federal funding and, the government claimed in a filing, had a role in interstate commerce.

Hiland resigned from his federal post in the final weeks of Trump’s presidency and is now working on Sarah Huckabee Sanders’s gubernatorial campaign; Sanders recently nominated him to be the next chair of the Arkansas Republican Party. Hiland didn’t respond to our calls and texts regarding this story.

Meanwhile, local pro-Trump Facebook pages tracked Jeffrey’s and Lung’aho’s cases. During an early pretrial hearing for Lung’aho, over a dozen men wearing paramilitary clothing and carrying rifles loitered on street corners near the courthouse.

For most of the past year, Jeffrey and Lung’aho were held in separate wings of the Greene County Detention Center in rural Arkansas. Judges revoked bond for both of them less than a year after they were arrested. The courts faulted them for failing tests for cannabis use, missing check-ins, and, in Lunga’ho’s case, an arrest for public intoxication. Recently, after pleading guilty to a single count of conspiracy to possess a destructive device, Jeffrey was transferred back to a detention center in Little Rock.

As both cases have plodded along for nearly two years, Jeffrey’s supporters have continued their efforts to raise awareness and funds. She eventually hired Phillip Hamilton, a New York City–based corporate lawyer, as her counsel. In a motion to appeal her ongoing detention, Hamilton described Jeffrey’s distress: Her long separation from her 12-year-old daughter and her family had reached “the point where it was making her mentally and emotionally sick,” Hamilton wrote, adding that he had been unable to communicate regularly with Jeffrey because of staffing shortages at the Pulaski County Regional Detention Facility.

When Jeffrey spoke to us in January, she described the pain of the family separation, noting that she was her daughter’s primary caregiver. In the messages she sends to her daughter, “I’m always reflecting that I love her, and that she’s my forever,” Jeffrey said. “It’s really hard not being in her life, making her lunch and dinner, tucking her into bed.”

Lung’aho is still fighting his case and hoping that his battle can help others in his position. In November 2021, Kaiser filed a motion urging the judge to consider whether prosecutors had stretched “the reach of federal criminal law beyond its constitutional bounds.” He argues that the Justice Department lacks jurisdiction in the case, pointing out that federal funding for the affected police agencies is minuscule. “From minute one, we’ve said this is a state case charged federally because of politics,” Kaiser said in an interview.

Almost a year later, US District Judge D.P. Marshal ruled that although the destroyed police cars were not federal property nor purchased with federal financial assistance, Lung’aho could still be federally charged with arson. But Marshal dismissed three of Lung’aho’s 13 charges, each of which prescribed a 30-year mandatory minimum sentence, for using a destructive device during a crime of violence. “Federal arson is not a crime of violence,” Marshal wrote—at least in Lung’aho’s case.

The ruling dropped Lung’aho’s maximum prison sentence from more than 90 years to somewhere between 10 and 30, according to Kaiser. But federal prosecutors immediately filed an appeal to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, which could take up to eight months to issue a ruling—and Lung’aho would remain in jail the whole time.

If the ruling is upheld, he is considering going to trial, despite the risk of prison time and the extraordinarily low success rates of federal defendants.

“Ten years is scary, but the 30-to-life is what they threatened at the beginning, and now it’s all gone,” Kaiser said the morning of the ruling. Lung’aho is more willing to face a jury “now that the potential sentence for accepting a plea deal is only slightly better than what we’d face at trial.”

Meanwhile, Jeffrey’s incarceration has been a devastating coda to a summer that initially held so much hope for change. Since then, the GOP-controlled Arkansas legislature has passed a raft of regressive bills loosening checks on police and private militias and restricting public education under the guise of stopping “critical race theory.”

The surveillance and prosecutions “crumbled the activist movement in Arkansas, because nobody can trust anybody,” said Brooklen Mason, a Little Rock activist who knows Jeffrey and several other defendants. “And part of the work is being able to trust people.”

The ACLU’s Dickson agrees, noting that Jeffrey’s long incarceration has had a “chilling effect” on local activism. “That’s not a defect,” she said. “That’s part of the design.”

This story was produced with support from the Puffin Foundation and the Fund for Constitutional Government.