This story was produced with support from the Fund for Constitutional Government.

The small city of San Luis is tucked away in the far corner of Arizona, closer to Mexico than to any major U.S. city. The community is nearly 95% Latino and tight-knit — the type of place where you know your neighbors and their parents and cousins.

It’s not uncommon here for residents to frequently cross the border into Mexico to go shopping or see a dentist, as the vast majority of residents are U.S. citizens who can go back and forth freely. And they do not take their right to vote in the U.S. for granted. Election Days in San Luis were typically joyous occasions, with music and celebrations in the streets.

Luis Marquez, the president of the local school district and a community leader in San Luis, said they felt “like a state fair.”

“Everybody would get involved, people would have their carne asada and music and it was just something very active,” he said.

But election celebrations have stopped here in recent years. A 2016 law pushed by state Republicans made it a felony punishable by prison time to collect a voter’s ballot unless the collector is their relative, household member, or caregiver. Since then, the excitement and joy surrounding voting have been replaced with fear. “Now, it’s been really quiet,” Marquez said. “There’s no action.”

In some states, there’s no prohibition on collecting ballots from other community members, a common occurrence in places where residents have limited access to polls. But Arizona is one of more than 30 states that restrict or ban the practice.

The law was signed in 2016 and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2021 after it was challenged in the lower courts. Since then, the Arizona attorney general’s office has prosecuted four community members, including the city’s former mayor, Guillermina Fuentes, who was jailed for 30 days, for alleged unlawful ballot collection.

Allies of former President Donald Trump say these arrests are indicative of the type of voter fraud that cost him the 2020 election. But democracy advocates say prosecuting these cases suppresses the right to vote.

“This is what opponents of the ballot collection law always feared – the arbitrary enforcement of the law against people of color, women of color, without any kind of evidence of any type of fraud or intent to do wrongdoing” said Darrell Hill, policy director for the ACLU of Arizona. “These are people who are just helping their neighbors, helping their community, and are now facing serious charges.”

On Oct. 13, Fuentes, a 66-year-old grandmother, former farmworker, school board member, and local Democratic leader, was sentenced to one month in jail and two years of probation for collecting four completed mail ballots that belonged to community members during the August 2020 primary. Fuentes and her neighbor, Alma Juarez, were the first people prosecuted under the state’s ballot collection law.

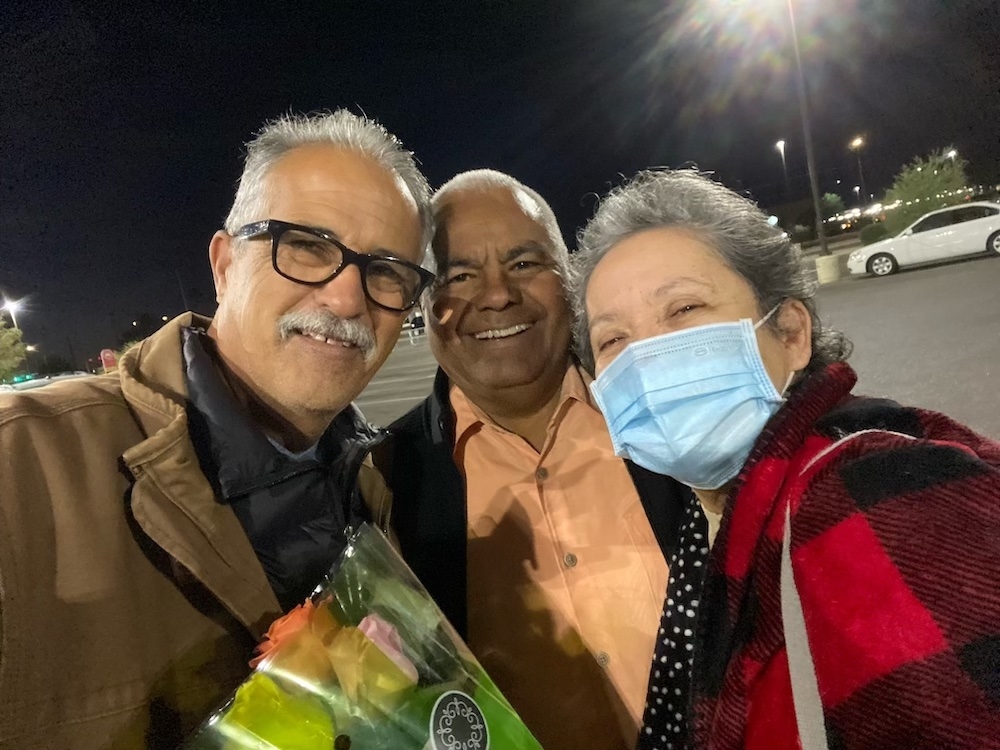

From left to right: Luis Marquez, Manuel Castro and Guillermina Fuentes after Fuentes was released from jail. Image: Luis Marquez

Her prosecution by the office of former Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, who was running for U.S. Senate throughout much of the legal proceeding, became fodder for conspiracy theorists and the right-wing elections group True The Vote, which publicized the case nationally.

In an interview after she was released from jail, Fuentes described the initial shock of her indictment. At the time of her offense, Brnovich’s office had petitioned the Supreme Court to hear a case focused on the law, and there were legal questions about whether it was constitutional.

“When I was about to go to jail, I was so sad and frustrated, and I couldn’t believe that I was going, because I see it like a witch hunt,” she said. Brnovich, who is no longer in office, could not be reached for comment and Todd Lawson, the prosecutor with the attorney general’s office who worked on the case, did not respond to a request for comment.

On Oct. 19, Brnovich announced two more indictments against women in the Democratic-leaning town within a county that voted for Trump by 6 points in 2020. The attorney general’s office alleges that the women collected eight ballots between them.

Fuentes’ daughter, Lizette Esparza, said she wakes up each morning in fear of how conspiracy theorists will talk about her family on social media.

“We’re living in a nightmare right now,” said Esparza, who serves as the superintendent of the local elementary school district. She also worries about how her mom’s ordeal will affect the community. “They’re not going to want to go to vote, especially now because now they’re scared.”

Casting ballots in San Luis

Like a town square, the San Luis post office is a major hub of this border community. During business hours, cars steadily stream through the parking lot as residents, on their way to or from work or school pick-up, run inside to check their P.O. boxes.

San Luis doesn’t have home mail delivery. The city spans roughly 34 square miles, and it’s not uncommon for people to pick up mail for friends and neighbors, who may share P.O. boxes. The community is poor, with an average per capita income of just over $15,000. Many residents don’t have their own vehicles and there’s very limited public transportation.

Casting a ballot in-person can be difficult for people in San Luis. Like Fuentes, who dropped out of high school after 10th grade to join her parents and siblings planting and harvesting lettuce crops in Arizona and California, many San Luis residents are farmworkers who speak little English and spend long hours in the fields.

“They leave at 5 in the morning and come back at 7 or 8 at night,” Esparza explained. “When in the day are they going to have to go and vote?”

Arizona has permitted no-excuse voting by mail for more than 30 years. And before the ballot collection law was passed, it was not uncommon for residents of San Luis to rely on friends, neighbors, or volunteers to help bring their ballots to the post office or to help return them to a voting center or dropbox.

San Luis residents interviewed explained that they consider many in the community who are not blood relatives, like neighbors and close friends, their family. Limiting ballot collection to just family members, household members, and caregivers doesn’t make sense, they said.

“People who enacted this law are people who don’t want people in San Luis and Native communities to vote,” said Anne Chapman, Fuentes’ attorney. “That’s what this is about.”

GOP restrictions on voting

The Republican Party’s effort to restrict certain groups of people from voting has taken many forms over the last decade since the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act.

One of them is placing limits on ballot collection, or as Republican lawmakers pejoratively call it, “ballot harvesting.” Republican officials justify the laws by claiming that an individual or organization could pressure a voter to vote in a certain way if they return a ballot on their behalf.

“The intent behind the bill is to make sure that we have integrity in our electoral process, that there is a chain of custody when it comes to mail-in ballots,” said then-state Sen. Michelle Ugenti-Rita, who sponsored Arizona’s law when she was a state representative. Ballot collection, she said, “is ripe for a lot of things to go wrong.”

Arizona’s law, passed by the legislature in 2016, faced a lengthy legal challenge. Democratic groups sued, and in 2018, a federal district court sided with Arizona after a trial. But Democrats appealed to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which struck the law down, finding that it violates the Voting Rights Act by discriminating against minority voters.

Republican lawmakers, the court found, passed it with the intention of suppressing the votes of Native American, Hispanic and Black voters, who often face issues with mail service and access to transportation and who are more likely to rely on the assistance of third parties to return their ballots.

Brnovich appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the law in a 6-3 ruling in July 2021 that had major implications for voting rights across the country. In a dissent, Justice Elena Kagan lamented how the majority opinion further weakens the Voting Rights Act.

“What is tragic here is that the Court has (yet again) rewritten — in order to weaken — a statute that stands as a monument to America’s greatness, and protects against its basest impulses,” she wrote. “What is tragic is that the Court has damaged a statute designed to bring about ‘the end of discrimination in voting.’”

On Aug. 4, 2020, the day of Arizona’s primary election, the law was still relatively new and was still being litigated in the courts. Fuentes was stationed outside a local cultural center to support city council candidates and hand out campaign literature. At one point during the day, Fuentes’ neighbor, Juarez, approached her and handed her a ballot.

What Fuentes didn’t realize was that Gary Snyder, a local Republican, was recording cell phone video outside the polling place. In the 2020 primary, Snyder was running for city council as a write-in candidate and in 2022 he would run for state Senate. Both attempts were unsuccessful.

A campaign sign for local Republican Gary Snyder. Image: Kira Lerner/States Newsroom and Type Investigations

He shared the footage with David Lara, another local Republican who had unsuccessfully run for office numerous times in San Luis. In an interview, Lara and Snyder said the footage showed the type of voter fraud that has swung elections in San Luis for decades.

“If there would have been 10 Gary Snyders with cameras, we would have caught many people doing the same thing all throughout the day,” Lara said.

“Out of 10 elections in San Luis, eight or nine have been won because of fraud,” he added.

In the video recorded by Snyder, Fuentes appears to write something on the ballot and then hands Juarez a stack of ballots to bring into the polling place. The interaction was the type of voter assistance Fuentes had provided for countless other community members. Yuma County officials later verified that the voters signed their own ballot envelopes, and the ballots were counted.

The Yuma County Sheriff’s Office and the state attorney general’s office eventually learned of the footage, and Brnovich’s Election Integrity Unit launched an investigation. People in San Luis reported that uniformed sheriff’s deputies knocked on their doors early in the morning to ask about their voting history, which alarmed many residents, according to a brief filed by Arizona voting rights groups in the Supreme Court case.

Prosecutors charged Fuentes with conspiracy, forgery, and two counts of ballot abuse. In court documents, the state said Fuentes “appears to have been caught on video running a modern-day political machine seeking to influence the outcome of the municipal election in San Luis, collecting votes through illegal methods, and then using another person to bring the ballots the last few yards into the ballot box.” She pleaded guilty to one count of ballot abuse, a felony, and the state dropped the more serious charges.

Lara and Snyder said that Catherine Engelbrecht and Gregg Phillips, the leaders of True the Vote — a far-right group that has promoted conspiracy theories about voter fraud — reached out to them. The claims of ballot harvesting in San Luis became a crucial component of “2000 Mules,” a documentary directed by right-wing filmmaker Dinesh D’Souza in May 2022 which falsely claimed that voter fraud, specifically a significant amount of ballot harvesting by so-called “ballot mules,” swung the results of the 2020 election.

“They’re the ones that actually helped us to make this problem national,” Lara said in an interview.

But many in San Luis said they don’t trust Lara and Snyder, whom they described as disgruntled former candidates for office who are trying to discredit Democrats. Yuma County Supervisor Lynne Pancrazi said she is upset by the national reputation they’ve attached to San Luis. They “are giving such a bad name to this community,” she said.

Fuentes jailed, held in isolation

Across San Luis in mid-October, people who know Fuentes appeared shocked that their friend and former mayor was two dozen miles away in Yuma, Arizona, jailed and held in isolation for a month either because of her age and health or her position as a public figure. Chapman said the jail has given different explanations for why she was held in a cell alone.

Soaking in the October sun outside the San Luis library, Pancrazi, who served as a character witness at a hearing prior to Fuentes’ sentencing, described Fuentes’ quiet but caring demeanor.

“She’s not a criminal,” Pancrazi said. “She’s someone who was helping her community just like she’s done her entire life.”

Manuel Castro, a pastor at the Gethsemane Baptist Church in San Luis, agreed. “It’s too much punishment for people doing a little mistake,” he said. “In my opinion, it’s a little mistake.”

The harsh sentence will also help conservatives “further the narrative that there is actual fraud in our elections, which there was no evidence of here,” said Andy Gaona, a Phoenix-based election lawyer who represented Fuentes in a special action petition with a state appeals court.

San Luis residents also lamented the inequities in voter fraud prosecution. Brnovich’s office requested a year in prison for Fuentes, and while the judge only sentenced her to a month in jail plus two years’ probation, even that is inconsistent with the sentences others have received for similar crimes.

Chapman commissioned a report from Rich Robertson, a legal investigator and former journalist, to put the state’s recommended sentence into perspective.

Robertson’s report detailed 79 prosecutions for voting crimes in Arizona between 2005 and August 2022. In general, he found that, other than Fuentes, people without a prior criminal history or who are not already imprisoned do not receive jail or prison time for voting crimes.

“Nobody goes to jail or prison for this stuff, unless they’ve already had some kind of priors,” Robertson said. He found two exceptions: One person who received a suspended sentence, and another was also convicted of influencing a witness and not just a voting crime.

In one notable example included in Robertson’s report, Brnovich’s office requested a lighter sentence for Tracey Kay McKee, a 64-year-old Republican white woman in the more affluent city of Scottsdale, Arizona, who pleaded guilty to casting a ballot in her dead mother’s name. She was sentenced in April to two years of probation and no jail time.

Juarez, who carried the voted ballots into the polling place, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and was sentenced to one year of probation and no jail time.

Robertson said he believes there were “a lot of political aspects” to this prosecution and that Fuentes was given a harsher sentence because of the national attention and her prominence as a target in the far-right “Stop the Steal” campaign.

“There was a lot of political pressure being exerted all over the place to make an example out of this particular defendant,” he said. “If it hadn’t been for the national spotlight being on Yuma County and Ms. Fuentes, I don’t think this outcome would have been the same.”

Norm Eisen, a longtime election lawyer who advised the Obama White House on ethics and government reform, called Fuentes’ sentence an “outrageous miscarriage of justice.”

“The relatively narrow conduct that formed the basis of the sentencing should not result in jail time and indeed in the vast majority of the United States, would not do so,” he said.

He called Brnovich’s sentencing request “a tragic and a cruel posture,” especially in “a smaller community where this kind of a sentencing has a chilling effect, even on legal behavior.”

At a hearing in October, Fuentes’ attorneys presented a number of character witnesses who spoke about her childhood, her work growing a business, and her position as a leader in the community. But at Fuentes’ sentencing hearing, Yuma County Superior Court Judge Roger Nelson said he does not believe she accepted responsibility for her crime and that her role as a community leader, although admirable, actually works against her.

“Many of the things that were put forward as mitigating factors, I think they’re also aggravating factors,” he said. “You have been a leader in the San Luis community for a long time. People look up to you, people respect you, and they look to what you do.”

Life after jail

Fuentes was released from jail in November and is now back in the community on probation, coming to terms with having lost her voting rights for the next two years because of her felony conviction. She said she already knows of San Luis residents who have stopped voting after seeing what she went through.

“I say don’t be afraid,” she said, explaining what she tells her friends and neighbors in San Luis. “And they say, because you weren’t afraid, you were in jail, Guilla.”

Fuentes said that the San Luis community stood behind her throughout the legal process, showing up to support her and her family when she was at her lowest. The day she was released from jail, her family and friends gathered at her mom’s house. She walked in and saw the large crowd holding signs and two big pots of menudo, a traditional Mexican soup, that she had requested as her first meal back.

It was just what she needed — to be around friends and a home cooked meal after spending a month in isolation. “I lost 10 pounds in jail and I gained them back the day I left,” she said.

When Brnovich announced indictments of two more women — San Luis City Council Member Gloria Torres and Nadia Lizarraga-Mayorquin — in October for allegedly collecting other people’s ballots, Marquez said he feared that more people would face jail time. A representative for Kris Mayes, Arizona’s newly elected Democratic attorney general, said the office is still undecided on how it will handle their prosecutions, but Mayes has said she will transition the office’s Election Integrity Unit from prosecuting voter fraud to protecting voting rights.

Democrats in the Arizona House introduced a bill this session to repeal the ballot collection ban, but it’s unlikely to move forward given the Republican majority.

“It’s starting again for other people,” Castro said. “It never ends. It’s never finished. It’s so hard for the community, really. It’s so hard.”