Donnell Rochester knew he was a star by the time he turned 18. He thought of himself as an influencer, boasting 10,000 followers on one of his many Instagram accounts.

In one short video, Rochester is standing in front of a boarded-up rowhouse, wearing a fashionably torn denim jacket with a black purse on a silver chain hanging from the crook of his arm as he presses a finger against a wide pair of black glasses.

In a photo, he is wearing bright red pants and yellow shoes, along with a yellow shirt with a red dragon on it and a shiny, black fake leather jacket that matches his large rectangular shades. His hair is shaved tight on the sides and standing up on top, slightly red, in a way that both invokes the pompadours of seminal queer Black performers like Little Richard and Esquerita from the 1950s and the 1980s look of Grace Jones.

Rochester’s stream of selfies and Instagram Live posts was steady, spanning numerous accounts, and seemingly endless, until they abruptly stopped coming on February 19, 2022, when the 18-year-old was shot and killed by Baltimore Police officer Connor Murray during a traffic stop, from which he tried to flee.

Shortly after that, Rochester’s photos started appearing on other people’s social media accounts with the hashtag #JusticeForDonnellRochester. His mother, Danielle Brown, printed out his image on posters to display, first in front of City Hall and then the State’s Attorney’s Office, while she and a small group of supporters demanded action against her son’s killer.

Rochester was driving around with a friend when a specialized Baltimore Police squad called in his plates and began to chase him through a residential area. Rochester jumped from the car to flee on foot, then got back in the car and tried to drive away. Officer Murray stood in front of the car and shot at Rochester three times, before falling to the side and firing the final, fatal shot.

A report by Maryland’s Attorney General’s Office declared there was probable cause to charge Murray with second-degree murder or manslaughter, even if it would be a difficult case to win. Despite this, State’s Attorney Ivan Bates announced in January, “after careful analysis of the evidence,” he would not bring charges against the officers who were involved.

This is the first of a two-part investigation of the police shooting of Donnell Rochester. But in order to understand the cost of such a shooting, we must try to understand the life that was lost. An upcoming installment of this story will examine the events—and the decisions made by multiple agencies—that led to Rochester’s death.

Donny and Danny

Almost as common as selfies on Donnell Rochester’s social media were pictures or videos of his mother or posts directed to her.

On February 18, 2020, almost exactly two years before he was killed, Rochester posted a picture of Brown with the words “My beautiful mom thanks for being the best mother any child could ever want love you mom.”

On his mother’s birthday in 2021, he posted two videos of them dancing. In one, he dances and she follows his moves, shaking her head skeptically after he shakes his butt in front of the camera, but then she follows his lead until both break out in laughter. In the other, the mother and son look ecstatic as they dance.

Whenever they used to sing “Can You Stand The Rain” by New Edition, they always argued about who would sing which part. And they often arrived at the same solution, switching parts the next time around.

“This little boy really changed my life, like made me be the person I was today,” Brown says of Donnell, who was born September 7, 2003.

“If you knew Danielle from growing up, Danielle [was] always out here fighting, in the streets out here really getting it,” Brown’s sister Markia Jackson said. “Donnell really changed her life for the better. Like Danielle was out here. But Donnell, he came and grounded Danielle to be the person she is today for real.”

Rochester attended New Song Academy in Sandtown-Winchester, near Gilmor Homes, a West Baltimore public housing project, where the family lived. He loved the charter school and did well in group performances. But he also struggled academically and with behavior issues.

While in elementary school, he got into the Big Brothers Big Sisters program, where he started spending time with Joe Heinrichs, who had just moved to town. “My own personality is pretty shy, reserved. And I thought they would give me a kid that was kind of like that. But they matched me with Donnell, who is this loud, vibrant kid. And at first, I was like, I don’t know how to handle all this energy,” recalls Heinrichs. “At first, starting out, I thought it was my job as his mentor was like teaching things. But I mean, he rubbed off on me, you know, I think as much as I hope that I’ve rubbed off on him, he brought me out of my shell.”

Photos courtesy Danielle Brown

Photos courtesy Danielle Brown

Heinrichs, who is white, always let Rochester control the music in the car, and it was always Nicki Minaj. “I mean, at first, when he was like nine, I was like it’s a phase he’ll grow out of it. But he never did,” Heinrichs says. “He was a die-hard Nicki fan from the time he was nine.”

Rochester dreamed of transforming himself into someone as stunning and attention-grabbing as Minaj. But, at the time, the material conditions of his world were far from glamorous. His father, Randy Rochester, who people knew as “Grip,” was sentenced to 9 years in prison in 2010, pleading guilty to armed robbery, and in 2012, a judge ruled that Randy’s incarceration meant he did not have to pay child support.

And Gilmor Homes was notorious for its deplorable conditions, with reports of rats, mold, and management problems, and the neighborhood was known as a “high crime area” to police.

But Rochester was happy with the support of his stepfather and the women in his life.

“Donnell was truly my fave. I called him sis. He was my fave, my sis, my everything,” says Jackson. “We were more than a typical aunt and nephew. We were like sisters. That was how we acted toward each other. He was my baby sis.”

He had a little sister, too, and often posted about her during his time in Gilmor. On April 10, 2015, he posted a selfie with the date April 19 — his sister’s birthday — at the top and the words “You Are Invited” in purple at the bottom.

His mother responded to the post: “How is you postin a pic about someone else bday with your face. Not to mention why is you on fb. You supposed to be in. class.”

All Night, All Day

Two days after that post about his sister’s birthday, on April 12, 2015, around 8:40 a.m. on a beautiful spring morning that had all the elders in their Sunday best on their way to church, three of Rochester’s neighbors went to buy breakfast. They all grew up around Gilmor and usually hung out on Bruce Court, where Rochester might have seen them around. If he knew them, it would have been as B-Low, Daddy Daddy, and Pepper.

As the three young men walked down the street, Pepper made eye contact with a police officer on bike patrol. The new state’s attorney, Marilyn Mosby, had asked the police department to have extra enforcement in the area because there had been a surge in crime. The officer looked back at Pepper, and Pepper started running. Three white bike cops chased him through Gilmor Homes, finally catching him at the corner of Mount and Presbury streets.

Residents gathered outside as the police dragged Pepper, who was screaming and did not seem to be able to use his legs, toward a police van. Pepper’s legal name was Freddie Gray. He died of the injuries the officers inflicted one week later, on April 19, Donnell’s sister’s birthday, when they’d planned to have a party.

The area around Gilmor Homes became the center of the uprising in Baltimore, with nightly protests ending in skirmishes between police and protesters. The Western District Police Station, near Gilmor, was fortified and militarized with hundreds of shield and club-wielding cops. “When they was protesting, me and Donnell, I took my son with me so he could see,” Brown says. Both Brown and her husband, Donnell’s stepfather, feel like the experience shaped his view of police.

A study of policing in Sandtown-Winchester, the neighborhood that houses Gilmor Homes, described the dynamic between the police and the community as “over-policed, yet underserved.” Calls for service would go unanswered, while “jump-out boys” would harass residents going about their business, violating their constitutional rights.

On April 27, following Freddie Gray’s funeral, someone — no one has been held accountable yet — shut down the public transportation many kids relied on to get home from school. As a result of this shutdown, hundreds of kids in West Baltimore arrived at the transportation hub of Mondawmin Mall to find lines of riot police instead of buses.

Soon the police began to attack the children, who threw rocks and bricks and bottles back. Police used tear gas and fired projectiles at high school students just a couple years older than Rochester. Education reporter Erica L. Green tweeted a video from the scene that showed an officer throwing a brick at the students, calling it an “all out war between kids and police.”

Public officials almost simultaneously promised to do better for the city’s children and demonized them. “Too many people have spent generations building up this city for it to be destroyed by thugs who, in a very senseless way, are trying to tear down what so many have fought for,” then-Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake said of the rioting youth. Then-President Barack Obama echoed this sentiment, also using the word “thug” in a speech shortly before sending his education secretary to town to help address the structural challenges these students faced.

But the tear gas hung in the air and helicopters circled relentlessly overhead long after the cameras and news crews had moved on to the next story and families like Rochester’s had to help themselves.

Like the politicians, after the death of Freddie Gray — which ultimately prompted a Department of Justice investigation and federal consent decree — the Baltimore Police Department promised reform, including the implementation of body-worn cameras. In reality, the reforms simply increased the “over-policed yet underserved” dynamic that had already characterized BPD. A Johns Hopkins study reported a 30 percent decrease in arrests between April and July 2015. But the dynamic was complicated. While patrol cars sat idle, with officers reporting that they were afraid of being prosecuted if they made a false move, plainclothes squads in unmarked cars continued to wreak havoc on the “high-crime areas,” and especially the Western District, which contained Gilmor Homes.

Former officer Maurice Ward testified in federal court that during this period, his squad would often make 50 unconstitutional stops a night, seizing guns — and often stealing drugs, which caused additional problems.

But at the same time, there was also a dramatic spike in violence, much of it in the Western District. Over 40 people were murdered in Baltimore in May 2015, 10 of them in the Western District. A seven-year-old boy was among those killed that month. May was not an anomaly, as bodies continued to fall all around Rochester and his family throughout the year. This prompted increasing calls for more aggressive, proactive policing. Citing violence, the mayor fired Anthony Batts, the Black, reform-minded commissioner, and replaced him with Kevin Davis, a white officer who had worked in police departments in the region for two decades.

As a result of this dynamic, residents in the Western District found themselves feeling trapped between violent criminals on the one hand and violent police on the other.

Time Magazine happened to catch the 12-year-old Rochester for a follow-up on the neighborhood a year after the uprising, as the family was preparing to move to the county.

“I’m happy I’m getting out of here. We’re basically moving to Hartford County,” Rochester told the journalist. “Gilmor Projects is something else. Gilmor Projects, they do anything in Gilmor Projects, it’s a lot of shootings, it’s a lot of killings. It’s just everything. Basically a child wouldn’t want to grow up in Gilmor. I know I didn’t.”

Getting Out and Coming Out

After Rochester’s family moved away from the city, his father, Randy Rochester, got out of prison and began to play a role in his son’s life. “His father was coming around. They started spending time with each other,” Angela Woodward, Donnell’s maternal grandmother, recalls. “I told him his father and his mother were young when they had him. His father wasn’t always there for him, but he was there.”

In every picture of Rochester and his father, Donnell boasts a big smile. In one, taken when they went out to dinner together, Donnell sits beside Randy, both making a rock-n-roll devil horns hand gesture. Donnell looks delighted.

Then, on June 25, 2017, Randy was shot and killed in East Baltimore.

“I would sacrifice everything I had right now to have my farther [sic] here with me,” Rochester wrote on Facebook the next day.

“Sitting on my bed thinking bout [the funeral on] July 8,” he wrote in a caption for a photo of his father. “I don’t know how I’m going to ack I might not make it back to my seat it going to be really hard when they close that casket, I just wish I was there when you was at grandma’s. Just know I’m going to make you happy.”

In his confusion and grief, Rochester turned, as always, to his mother.

“Talking to my mava helps me get through wat I’m going through love you.”

“Love you more,” she replied.

“It was real bad,” Brown says. “[Donnell] just couldn’t understand it. He was only, what? 15. So, it was hard for him.”

He was also struggling with his behavior in school, to the point where Danielle had come to expect regular calls from irate teachers or administrators.

But that changed when Donnell came out as gay. “When he came out, it was like I didn’t recognize this person because it was like no phone calls from school, him just being a kid. He had friends now,” Brown says.

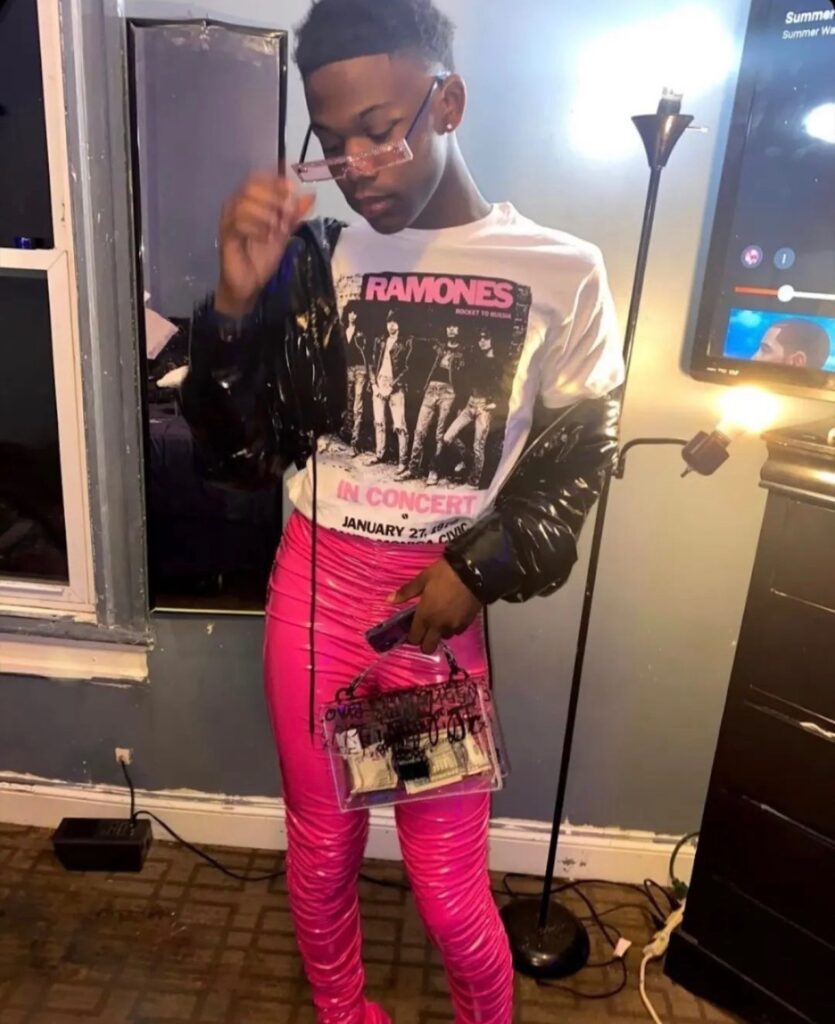

Donnell began to transform himself and let go of a lot of the anger that came from hiding his true identity, she believes. And he began to develop his idiosyncratic sense of fashion. “Once he got to 16, he owned it,” Brown says. “Cutting up his clothes, making his little outfits.”

Deniim, a trans woman, noticed Rochester on Instagram, where they followed each other. “He was just so raw with who he was, and his personality was loud and a lot of people couldn’t take that,” she says.

Deniim was older and more experienced than Rochester, but understood what he was going through. “I reached out like, hey, you know, it’s hard, you’re brown-skinned….I want you to be my son,” she recalls. “The way that normally works is you will take someone under your wing and try to show them the ropes of gay life.”

Part of her duties as Rochester’s “gay mom” was to teach him how to react to homophobia. “That’s part of, you know, the gay parenting on my end, telling him you can’t react to everything. It’s going to come with the life that you live, you know,” she says. “But to him being who he was, he wasn’t going to allow anyone to disrespect him.”

“You don’t call him a f*g or he’s gonna fight you,” Brown recalls. “He said that’s just too disrespectful for me.”

“That mouth! He’s gonna cuss you out,” Deniim says. “But outside of that, he’ll be the sweetest person ever.”

Even when Rochester was sweet, he had brutal wit and humor. “He was funny. Boy mouth was just terrible,” Deniim said. “Like say we cracking jokes and stuff like that, talkin about each other, playing—he will get you. Like he was definitely funny, like he had no filter.”

When she was younger, Deniim was into the voguing ballroom scene in Baltimore, and Rochester began to ask about how to get into that life and join one of the scene’s “houses.” Deniim told Rochester that he’d need to start going to events to be chosen and invited in.

Rochester would sometimes wear Deniim’s weaves and make videos, but he wasn’t interested in drag. “His dress was very outspoken because of course it wouldn’t be normal for a guy, but he dressed how Donnell wanted to dress. But it was him.”

Brown took Rochester to New York, where he posted from in front of the “CAMP: Notes on Fashion” sign in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Every year I use to watch the Met Gala on E! News talking about I wanna watch the celebrity’s [sic] go in, now I can see it in person.”

Rochester loved such trips. He wanted to move to Los Angeles to begin his ascent to wider fame on social media and, perhaps, in music. He turned 18 in September 2021, got a job at Amazon, and saved up for a car.

“That’s all he would talk about,” Deniim recalls, laughing. “He would [jokingly] say, when I get that new car, I’m gonna run you over.”

In late January 2022, just as the family was preparing to move back to the city, Rochester and three friends called an Uber around 3:00 a.m. When the driver showed up, he refused to take all four passengers. Rochester told his mother that there was a dispute and the driver locked them in the car and he ended up taking the driver’s camera. Brown thought that was all there was to it. But Rochester confided in Deniim that the issue could cause problems. The Anne Arundel County Police issued a press release and news outlets picked it up.

But nothing seemed to have come from it by February, when Rochester had moved with his family back into the city and bought a white 2016 Honda Accord.

“He was just so excited. He was like ‘yeah, I got my car, I’m about to pull up on you,’” Deniim recalls. “And I believe he’s playing. ‘You ain’t got no car!’…and he actually pulls up in his car.”

Rochester stayed at Deniim’s and took her to work the next morning. “It was Valentine’s Day,” Deniim says. “And he was like, come on, I got to get to my Mother’s house, she’s not answering her phone.”

“He wouldn’t let nobody drive that vehicle and he was just so proud of it because he did it on his own,” Brown says.

“I told him not to get the car,” Melchoir, Rochester’s stepfather, says, “But he had his mindset. He just went for it [and] got the car, he was so proud.”

To a young gay man who had just turned 18 and had big dreams, a car was a necessary step to success.

“He said there was nothing here,” Brown recalls. “And he wanted to go [to California] to pursue what he wanted to do.”

This story was produced with support from the Wayne Barrett Project. Additional reporting by Jasmine Braswell.

Correction: June 15, 2023:

A previous version of this article stated that Rochester purchased a Honda Acura. In fact, it was a Honda Accord.