This series was supported by the Pulitzer Center and produced in partnership with the nonprofit newsroom Type Investigations, with additional support from the Gertrude Blumenthal Kasbekar Fund and the Puffin Foundation.

MANILA, Philippines — It all happened so fast for Diane Mae Gamboa. One day in March 2022, she walked into the US embassy for an interview. A few days later, her visa was approved, her passport was stamped, and a green card was on its way. There was a nursing job waiting for her at a long-term care facility in Schenectady, New York, some 8,700 miles from her home in Puerto Princesa, a city tucked into a shimmering bay on the white-sand island of Palawan.

Gamboa, then 35, would soon be heading to the United States, where a crisis was unfolding. Wave upon wave of COVID infections had eviscerated staff at hospitals and nursing homes across the country, leaving them reaching for increasingly desperate ways to cope. Nurses were loaded up with ever-more patients, straining the limits of safety. Shifts were stretched beyond the standard 12 hours. In Washington state last October, a nurse called 911 from inside an understaffed emergency room, pleading for support. “We’re drowning,” she said.

Gamboa, nervous and excited, felt swept up by the speed with which the US system pulled her to work in the country. “Even if it scares me,” she said, “I’m just going to go.”

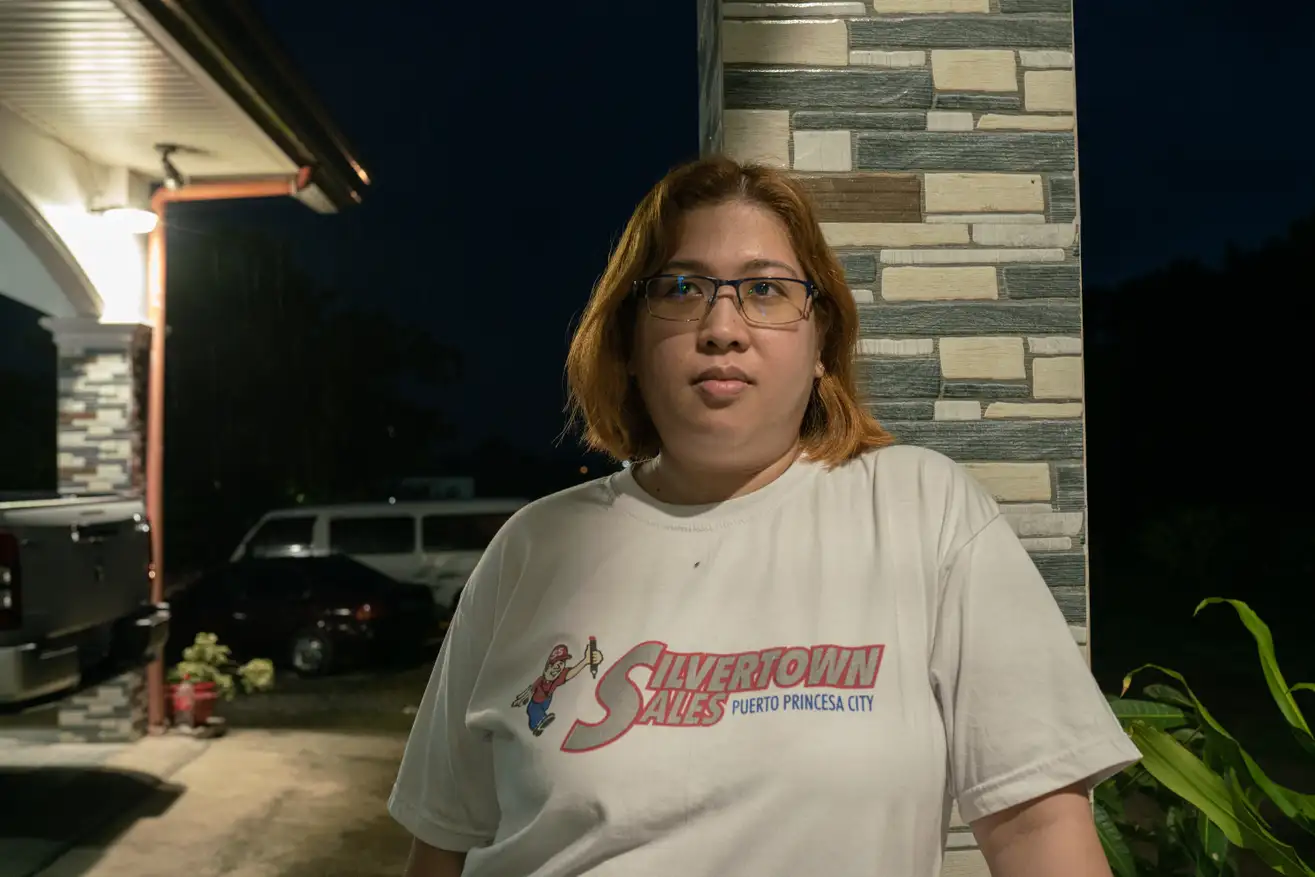

Diane Mae Gamboa, the night before she flew from the Philippines to the US. Image: Kimberly dela Cruz/Quartz

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, from February to April 2020, the US healthcare sector shed more than 1.5 million jobs, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics—nearly 10% of the total healthcare workforce at the time. And the nursing shortage is set to grow significantly worse in the coming years. According to research by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 45 percent of nurses surveyed in 2022 reported experiencing burnout, and nearly one-fifth of the current workforce plans to leave the profession by 2027.

To bolster their workforces, hospitals in the US and Europe have dramatically accelerated hiring from countries like the Philippines, India, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Jamaica. These countries have long sent trained, experienced nurses to work abroad. But since the start of the pandemic, what was once a steady trickle of nurses leaving their home countries has become a flood.

Quartz, in partnership with Type Investigations and with support from the Pulitzer Center, traveled to India, Nigeria, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, and the United States to investigate the consequences of this global movement of nurses. We spoke with more than 35 nurses, along with recruitment agency employees, hospital officials, public health experts, government health agencies, and researchers. Our investigation found an international bidding war for healthcare workers, yielding opportunities for some nurses but exposing others to exploitation—and leaving poorer health systems scrambling to cope.

AMN Healthcare, a staffing agency based in Dallas and one of America’s largest international recruiters, said the number of foreign nurses it placed in US hospitals has increased by 300% since the start of the pandemic. The United Kingdom, facing a similar staffing crisis, created a new visa that fast-tracked applications and reduced fees to make it easier to fill positions with nurses from overseas. Other European nations made similar moves. Last fall, Germany struck a deal with the Philippine government to hire hundreds of nurses and provide specialized language classes, while Finland set a target of hiring 20,000 international nurses by 2030.

As of September 2022, the UK had about 114,000 foreign-trained nurses working in the NHS, a 66% increase from 2017/2018. The US does not keep official statistics on the number of international nurses working in its hospitals and care facilities, but CGFNS International, a Philadelphia-based organization that screens international nursing credentials for visa applications, received more than 17,000 applications from October 2021 to September 2022, a 109% increase since 2018. Nearly 60% of the applicants came from the Philippines.

For individual nurses, like Gamboa, taking a job in the US or Europe can be a rewarding opportunity. In the Philippines, nurses’ salaries can be as low as $360 a month, a fraction of what they can make in the US. In Nigeria, the burdens of a failing hospital system weigh heavily on nurses, who described working without electricity or basic medical equipment. Many nurses dream about the higher education and career advancement that may be available to them abroad.

A spare ward at a primary care center in Lagos, Nigeria. Image: Damilola Onafuwa/Quartz

But the current demand for nurses in the US and Europe has exacerbated imbalances in the global healthcare system, and exposed nurses to exploitation and abuse. In India, our investigation found a network of recruiters who twisted the prospect of jobs into a means to exploit nurses hoping to go to the UK. In the US, we found foreign nurses coerced into patching up a system so broken, domestic nurses are leaving it in droves. And in Nigeria, we saw how the exodus of nurses has caused the nation’s fragile healthcare system to crumble further, with little aid from the countries benefiting from its people’s labor.

Just as the US and other wealthy countries have flexed their power to hoard vaccines and outbid poorer countries to secure personal protective equipment during the pandemic, they are now increasingly siphoning off nurses from poorer nations. And nurses who find themselves locked into exploitative contracts or misled by unscrupulous recruitment agencies have little recourse.

Patricia Pittman, a professor of health policy and management at the Milken Institute of Public Health at the George Washington University, who has studied the international nurse recruitment industry, said surges in demand in the US can change lives, and health outcomes, in countries like the Philippines. “These unintended consequences on the history of nursing in these source countries, at a minimum, should be understood as a phenomenon, because they’re part of why we as a country need to do a better job when we think about planning our own nurse workforce,” Pittman said. “We’re just jerking countries around.”

Diane Mae Gamboa and her daughter at the airport in Manila, Philippines, on August 1, 2022. Image: Kimberly dela Cruz/Quartz

Still, thousands of nurses continue to seek out opportunities abroad, lured by the promise of a better life for themselves and their families. Four months after obtaining her visa, Gamboa packed up her home, left her three eldest children with her parents, and boarded a flight from Manila to New York with her husband and 2-year-old daughter, ready to respond to the American healthcare system’s call.

A manufactured shortage and a solution

For many hospitals, the ability to hire international nurses has long acted as a pressure valve. Countries like the US and UK have strategically underinvested in their nursing workforces and educational pipelines, knowing they can hire staff from overseas when demand is high, said Howard Catton, CEO of the International Council of Nurses, a Geneva- based federation of nursing unions.

While hospitals and staffing agencies say there is a shortage of workers, what nurses, unions, and researchers argue is that, rather, there’s a shortage of good nursing jobs.

The number of nurses sitting for board exams in the US actually has been increasing, said Karen B. Lasater, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing who studies understaffing. “What we do see is that nurses do not want to work in conditions that are being offered,” Lasater said.

Even before the pandemic, nurses were feeling strained. In a study of medical-surgical units in Illinois and New York that Lasater conducted, more than 53% of nurses reported a “high degree” of burnout, a statistic she said is a consequence of deliberate understaffing practiced by the industry for decades. Labor is often the single highest cost for a hospital, so keeping staff numbers low saves money.

“Hospitals don’t see the financial incentive to employ more nurses,” Lasater said. Rather than viewing nurses as essential for providing medical services that improve patient outcomes and save money through interventions that, for example, reduce the length of a patient’s stay, hospitals typically consider them to be a drag on the company’s bottom line. “Nurses are equivalent to bed sheets and linens, in the perspective of hospital finances,” Lasater said.

When the pandemic started, the strategy of operating with a razor-thin staff left hospitals reeling. As nurses quit their jobs, healthcare facilities threw money at the problem. They hired travel nurses—roving nurses from around the country who work on short contracts to plug critical shortages—and paid them staggeringly high rates, often more than $100 an hour. They plumped up bonus packages for staff members. And they began bringing in more nurses from overseas.

A new cohort of nurses during training at Gamboa’s former hospital in the city of Puerto Princesa. The hospital’s medical director said the quality of care at his hospital suffers when they have to train new nurses every couple of years to replace the ones who migrate to work overseas. Image: Geric Cruz/Quartz

Sinead Carbery, president of international staffing at AMN Healthcare, highlights the reasons why international nurses are valued so highly: They have 12 years of nursing experience, on average. They typically have worked longer hours than nurses in the US, often in less- resourced hospital environments, with each nurse responsible for more patients—developing skills that became even more valuable in the strained working conditions of the pandemic. And while an AMN Healthcare survey found that 81% of international nurses said they had experienced feelings of burnout, they also were less likely than their US counterparts to access mental health services, a point Carbery cited as a sign of these nurses’ resilience.

“You can imagine coming from a country that has less resources in which to do your job, and then you come to the United States, and here you have the technology to manage patient care well at your fingertips,” Carbery said.

Moreover, international nurses are often paid less than US nurses with similar levels of experience. International nurses reported signing contracts for between $28 and $33.67 per hour, similar to what recent US nursing graduates make. By comparison, the average salary for US registered nurses is $39.05, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

And crucially, it can be challenging for international nurses to resign. To come to the US, nurses typically sign contracts with staffing agencies that lock them into their jobs for two or three years, with hefty penalties for leaving their positions early. Our investigation found that nurses who left their jobs early have been threatened with lawsuits for damages in the tens of thousands of dollars, and in some cases up to $100,000. Employment agencies have suggested that nurses will be reported to immigration authorities and have their greencards taken away; they’ve also threatened to file lawsuits against nurses who speak out about mistreatment, including on social media.

More committed than most

The circumstances of their employment can place pressure on international nurses to accept difficult and dangerous working conditions. Alren Aure, 33, who worked through the pandemic in a hospital north of London, described feeling obligation and fear mixed with an expectation of gratitude that cornered nurses into accepting dangerous assignments.

“You’re forced into a situation where you feel like you have no choice,” Aure said. “Most of my Filipino colleagues are like that. They say, ‘Yes, ok.’ Especially if they’re just starting and new at their jobs. They’re afraid of speaking up.”

International nurses are frequently assigned to bedside positions, according to Aure and Carbery. Working face to face with sick patients is one of the most strenuous assignments in a hospital, with high burnout rates. During the early days of the pandemic, these jobs were also among the most dangerous of all.

“I don’t know of any nurse who doesn’t want to go abroad,” a doctor at Diane’s former

hospital in Puerto Princesa said. Image: Geric Cruz/Quartz

The imbalance revealed itself in a grim statistic: Among registered nurses in the US, Filipino nurses made up 30% of deaths from COVID-19 and related complications as of Sept. 16, 2020, despite making up less than 4% of the nurse population. In the UK, an analysis by The Guardian found that more than 60% of healthcare workers who died in the early months of the pandemic were minorities, despite making up only 20% of NHS staff.

The value proposition of international nurses—resilient, uncomplaining, with higher levels of experience, and a lower likelihood of quitting—makes them attractive to healthcare providers. But Zenei Triunfo-Cortez, the Filipino-American president of National Nurses United, the largest union of registered nurses in the US, sees these qualities as the outcome of exploitation.

“They did whatever they were told to do,” Triunfo-Cortez said of recently arrived nurses. “They thought they didn’t have any choice.”

Employers can leverage whatever gratitude nurses might feel for having been brought over as a way to get them to endure difficult or unsafe conditions. “It’s essentially a modern form of indentured servitude,” Triunfo-Cortez said.

Western demand for nurses shapes the health workforce in countries thousands of miles away

The pipeline that connects Puerto Princesa with Schenectady, New York, has been decades in the making.

Filipino nurses migrated to the US in large numbers following the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which abolished the national origin quota system that favored immigrants from Western and Northern European countries in order to maintain racial homogeneity in the US. A former US colony, with English-speaking nurses trained in an educational system based on an American model, the Philippines has been a particularly ripe recruitment ground for healthcare workers.

Migrant nurses told friends and family members back home about the relative prosperity of working overseas, and the profession came to be tied up with the myth of the American Dream. Between 1966 and 1985, an estimated 25,000 Filipino nurses immigrated to the US.

Another major recruitment drive occurred in the early 2000s, when US hospitals once again found themselves short of nurses due to poor working conditions, low wages, and heavy workloads. When Diane Mae Gamboa graduated from nursing school in 2008, she was among one of the largest cohorts of nurses the Philippines has produced in recent years.

As of 2021, according to the Migration Policy Institute, nearly 2.8 million healthcare workers in the US are foreign born, more than 18% of the total healthcare workforce. Filipino nurses make up 27% of foreign-born nurses—the largest share by far. Another 7% are from India, 5% each are from Jamaica and Mexico, and 4% are from Nigeria.

In 2007, the global financial crisis caused the demand for foreign nurses in the US to dry up. But the pandemic spurred another rush for Filipino nurses, one that’s more acute. Suddenly foreign governments were knocking on the Philippines’ door, generating a tug-of-war for nurses and other healthcare workers.

According to the World Health Organization, nearly two-dozen member states eased migration restrictions for healthcare workers in 2021 and 2022. Meanwhile, 17 member states—including seven developing countries—restricted the migration or recruitment of their healthcare workers in order to stave off their own shortages. The Philippines, for example, temporarily suspended the deployment of healthcare workers abroad in April 2020, then capped the number of visas it would issue at 5,000 per year that November.

Wealthy nations have been able to bypass these restrictions, however, and keep the supply of nurses flowing. The US grants permanent residency to the majority of international nurses, making those from the Philippines exempt from their government’s nurse deployment cap. The UK, which had allowed a previous agreement with the Philippine government to lapse, renewed it in 2021. Germany and Japan similarly have long-standing bilateral agreements with the Philippines, while Singapore, Canada, and New Zealand also have approached the Philippines about bringing in nurses beyond the official deployment cap.

The American Hospital Association (AHA), which in 2021 asked the State Department to prioritize visa processing for international nurses, forwarded a statement it made to the Senate in 2022, in which it outlined workforce challenges in the US and the contributions of international nurses to the healthcare system. It did not address the foreign nurses’ vulnerabilities to exploitation or the burdens that migration puts on the countries these nurses are drawn from. The AHA did not respond to a request for comment on issues of ethical recruitment.

Avant Healthcare Professionals, an international staffing agency, the Federation of American Hospitals, and the American Association for International Healthcare Recruitment, all of whom also lobbied for international nurse visas, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

For the countries supplying these nurses, the increased demand during the pandemic has wreaked havoc on local healthcare systems. According to the Philippine health department, the country was short of more than 200,000 healthcare workers as of September 2022, including more than 100,000 nurses.

During a visit in 2022, all of the nurses at a nurse station in Gamboa’s former hospital in the Philippines were in different stages of the process for migrating overseas. Image: Geric Cruz/Quartz

Surges in migration create considerable pressure on an already struggling system, but nurses are leaving not only for other countries, but for other industries. Of the 867,974 healthcare workers registered in the Philippines 2018, only 22% continue to practice, according to a 2022 article in The Lancet, suggesting that training more workers won’t mean they will stay in a health system with low pay, limited facilities, and unstable career prospects.

The Philippine government has tried to address shortages with programs that funnel doctors and nurses to the most severely understaffed rural areas, but without systemic reforms that improve pay and working conditions, the doctors and nurses leave their assignments within a few years. (The Philippine Department of Health declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Since the start of the pandemic, incoming email requests from hospitals exploded, according to a manager of a recruitment agency in Ortigas, one of Manila’s business districts, who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to speak on behalf of the company. Where hospital systems used to ask for a hundred nurses, he said, they were now asking for many times that amount.

And Filipino nurses were eager to take these jobs, said Bernard Olalia, the head of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration, a government agency that was recently folded into the newly-formed Department of Migrant Workers.

“The demand for nurses abroad,” said Olalia, “instigated the mass resignation of nurses.”

One of the world’s biggest suppliers of nurses is short of them

Up three flights of stairs in an aging building in northern Manila, the FDM Training Center was bustling during a two-day certification course for the American Heart Association in May 2022.

In a large room with the curtains drawn, an instructor speaking in rapid-fire English played the sound of a heartbeat over the speaker, a staccato of bleeps with the wet thumping of a valve. A couple dozen nurses strained to listen. “The patient is still in…?” the instructor prompts. “Pre-arrest,” the nurses respond in unison.

At the end of the second day the nurses would take a test. Passing it was a requirement for them to practice in the US, UK, and other countries.

Since FDM opened its doors a dozen years ago, 2022 was its busiest year, according to Maria Emelita Luansing, a former nurse who is the senior manager of the training division, and the owner’s mother. So far, 2023 has been even busier. Luansing could see how the struggle to maintain staff ratios at US hospitals spilled into the Philippine healthcare system. The nurses would enroll in FDM’s courses and help fill the need abroad, leaving local hospitals struggling.

“We cannot give the exact care the patient needs,” Luansing said of the Philippine healthcare system. “It’s a problem.”

On a warm day in May, a couple of months before Gamboa flew to the US, Paul Castillo, the medical director of her hospital, the Palawan Medical Mission Group Multi-Purpose Cooperative, or Co-op, said that he had two nurses’ resignations waiting for signatures on his desk. The surging demand in the US and other countries, he said, “has impacted hospitals negatively.”

When the Philippine health department assessed the Co-op’s staff in 2021, it determined that the hospital was short 49 nurses. Before the pandemic, the ratio of nurses to patients at the facility was about 1-to-5. Now it was as high as 1-to-18. “The quality of course suffers,” Castillo said. Furthermore, the more experience a nurse has, the better they are at gauging a patient’s needs, which leads to better outcomes. That “clinical eye” is lost if nurses cycle out of the hospital every couple of years, Castillo said.

Dr. Paul Castillo, the medical director for the Palawan Medical Mission Group Multi-Purpose Cooperative, said the surge in demand for Filipino nurses abroad, “has impacted hospitals negatively.” Image: Geric Cruz/Quartz

As Gamboa made her rounds before the evening shift change, four nurses sat in plastic chairs at the nurses’ station on the floor below, logging medications and linens, or filling out endorsement and discharge sheets. All of them were in different stages of leaving. One had passed her German language courses and was waiting for her papers to come through. Another was finishing up her required two years of work experience before starting her application to work overseas.

For many of the departing nurses, the decision to leave came down to money. During the pandemic, the hospital provided transportation for staff, and free meals during shifts. But their pay still only came up to a total of 22,000 pesos a month, or about $400. That couldn’t compete with what the nurses stood to make abroad.

“You make three to four times the salary, and so many benefits,” one nurse said. There’s also less of a workload, adds another, “so it’s a really nice life.” None of the nurses were worried about hazardous conditions or exploitative contracts. From the vantage point of the nurses’ station in Puerto Princesa, the outlook was uniformly rosy.

One of the doctors walked in and joined the conversation. “I don’t know of any nurse who doesn’t want to go abroad,” he said, and they all agreed.

Diane’s children talk to her in Schenectady, New York, by video call from Puerto Princesa, Philippines, in September 2022. Image: Geric Cruz/Quartz

Gamboa was among the last to leave the hospital that day. Her shift had stretched to 13 hours as she finished her paperwork and waited for her replacement to arrive. The light was dim when she had started at 6 a.m. By the time she left the hospital, the sky had turned a deep blue, and the cicadas had begun their twilight song.

Her family had just moved into their new house when her US visa came through. Her new washing machine, still boxed, sat in a corner of the living room. Now, instead of settling in, life remained in limbo. Folded clothes were stacked on the couch, some intended for suitcases, others to be given away. Her dog, a lab named Junior, was still a puppy. At night, when he curled up to the caretaker in the bamboo hut where he lived in a corner of their property, that seemed like a good enough solution to finding him a new home.

Gamboa’s three older children would go live with her parents. But her youngest child was just two years old—too young to leave behind. Her husband, who worked in the fire safety industry, would close up his business and come with her to New York, where he would take care of their daughter while Gamboa was at work.

It was a big change. If the hospitals in the Philippines could pay her a more competitive salary, Gamboa said she would have considered staying home. But the job in Schenectady would pay her thousands of dollars a month. She hoped she would be separated from the other children for no more than a couple of years, until she could bring them over, too.

Diane’s mother looks through old photographs during a video call. Image: Geric Cruz/Quartz

She knew she was paying a high price to move abroad, leaving so much of her life behind. But the money Gamboa stood to make in the US seemed to make such upheaval worth it. At the end of the day, staying home in the Philippines just didn’t make financial sense. “Practically speaking,” she said, “the salary is not enough to live on.”

Karla Garcia and Geela Garcia contributed research in the Philippines. Charts were produced by Clarisa Diaz.