This story is part of the Inside/Out Journalism Project by Type Investigations, which works with incarcerated reporters to produce ambitious, feature-length investigations. It was produced in partnership with High County News, a nonprofit magazine that covers the Western United States and its people, places and ecology.

The Mission Creek Corrections Center for Women (MCCCW) sits on Washington’s Kitsap Peninsula, a little over an hour’s drive west of Tacoma. The three units that comprise it are nestled in a forest between adventure resorts and off-road vehicle parks. Last winter, snow blanketed the rugged terrain and temperatures dropped to freezing, turning the roads slick with ice.

The countryside around the prison is beautiful, Tiffany Doll, a 51-year-old woman incarcerated there, told High Country News and Type Investigations. Tall trees surround it, and people inside often see deer and rabbits. Doll has a lot of time to observe the environment: She’s one of a handful of incarcerated women working on a project by Evergreen State College to raise, breed and release the endangered Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly. All year long, Doll meticulously monitors the conditions the larvae need to complete their cycle from egg to butterfly. In spring, she feeds them wildflower leaves and plantains grown on-site, and during winter, when they’re locked in a hibernation-like state called a diapause, she monitors the humidity of the terracotta containers they’re kept in. It’s a delicate balance; if the larvae get too hot or too cold, the environmental conditions too wet or too dry, they die.

Doll sees the irony of the contrast between the care she gives to the butterfly larvae and her own environmental conditions. She was transferred to MCCCW in September 2021, and throughout that first fall and winter, the boiler was continuously breaking. Staff allowed the women just one extra blanket and permitted them to wear hats in the dayroom, but the building was freezing. “This is the facility where we are getting released from,” she said. “It’s supposed to prepare women for the outside world.”

Many of Washington’s 12 prisons have been pushed to the brink by public health crises and years of neglected maintenance. Climate change could send them over the edge.

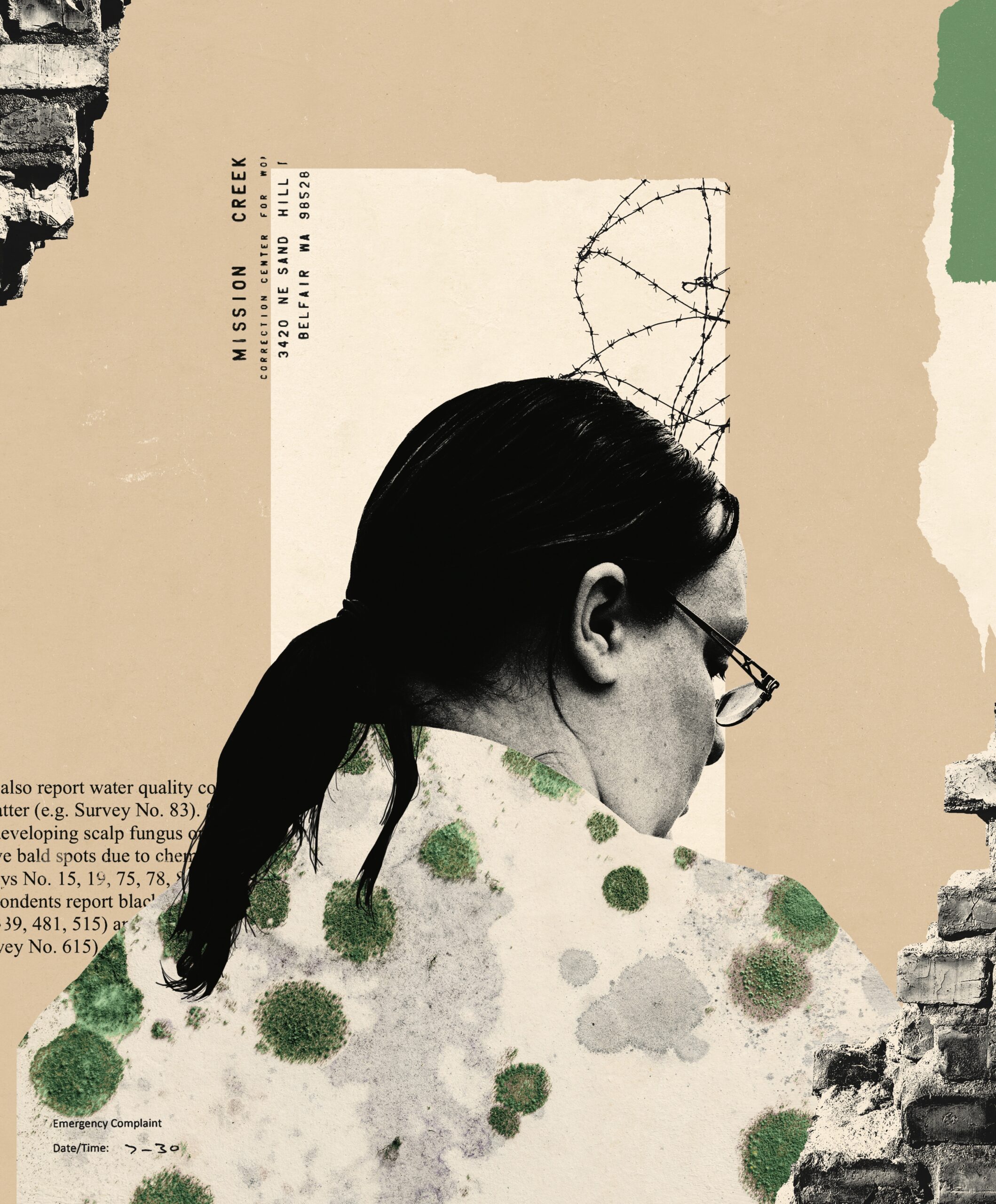

One of the original units — Mission Unit — was built over half a century ago and the age shows itself in the omnipresent smell of mold. Melinda Barrera, a 43-year-old woman incarcerated at MCCCW, lived in Mission for several months in 2022. Black mold covered the showers, she said, and the carpets were so thick with mold spores that a musty smell rose whenever anybody moved. A 2020 survey of incarcerated women by the Washington Office of the Corrections Ombuds, a state watchdog agency for the Department of Corrections, noted a host of similar problems.

Those surveyed reported shocking conditions: the roof in Mission unit caving in from the air conditioning, leaky ceilings and light fixtures, black mildew in the showers, ventilation units full of dust and hair, termites in the cupboards. Women developed scalp fungus or their hair fell out in clumps from chemicals and fecal contaminants in the water. One survey response, echoed by several of the five women we spoke to, said that Mission Unit was in such disrepair that it “needs to be condemned.”

Mission Creek isn’t the only prison struggling to keep its residents safe in an increasingly unpredictable environment. Many of Washington’s 12 prisons — including Washington Corrections Center, where Chris Blackwell, one of this investigation’s authors, is incarcerated — have been pushed to the brink by public health crises and years of neglected maintenance. Climate change could send them over the edge.

“We are locked into 1.5 degrees of warming,” Meade Krosby, the senior scientist with the University of Washington Climate Impacts Group, told HCN and Type. For Washington, that means a growing number of very hot days, higher chances of both increased flooding and drought, and larger and more frequent wildfires on both sides of the Cascades.

Black mold covered the showers at Mission Unit, and the carpets were so thick with mold spores that a musty smell rose whenever anybody moved.

The climate is warming at such an unprecedented pace that, unless we rapidly and immediately decarbonize our entire energy system, we are no longer able to only make small, incremental changes, such as installing AC units, Krosby said. “The change that needs to happen for us to be able to live sustainably on this planet needs to be transformative.”

Nowhere is this as true — or as urgent — as it is for prisons. Like prisons around the country, Washington’s 12 facilities are plagued by long-deferred maintenance and crumbling infrastructure. Even without the added impacts of climate change, prisons pose an ever-growing risk to incarcerated people.

This comes at a steep cost to the state: Last year, the Washington Department of Corrections, or DOC, submitted a 10-year capital budget request estimating that it will take nearly $800 million over the next decade just to maintain and repair current infrastructure. That estimate increases to $1.2 billion with new programming and basic upgrades, such as installing AC units in some prisons. According to the capital budget passed by the Legislature this year, the DOC received just over $80 million for the next two years.But infrastructure is just one part of the puzzle. The Washington DOC, like most corrections departments around the country, lacks a comprehensive climate adaptation plan, and there is limited agency guidance on how to keep incarcerated people safe during events like heat waves, as HCN and Type reported in the first installment of this investigation. Without infrastructure and planning, punitive measures — including solitary confinement, lockdowns and restrictions on the use of educational and recreational spaces — are more frequently employed, with negative impacts on incarcerated people.

Interviews with more than two dozen people incarcerated in eight prisons across Washington, criminal justice experts and advocates, as well as two public records requests and public documents revealed that 2022 was an inflection point for incarcerated people in Washington. It was the first year of a new normal, one in which climate hazards, a public health crisis and deteriorating infrastructure merged to create a different type of seasonal calendar, one experienced as much through restrictive policies regulating people’s access to the environment as through changes in the environment itself.

This leaves the state with two alternatives. It can spend massive amounts of taxpayer dollars to retrofit outdated infrastructure to keep people incarcerated in ever-worsening conditions. Or it can pursue an option that some advocates and policymakers are already paving the way for: Reducing the prison population, or decarceration.

Image: Cristiana Couceiro/High Country News

CHRISTOPHER HALL, a 49-year-old man incarcerated at Coyote Ridge Corrections Center in Connell, Washington, started feeling ill just a few days after the start of 2022. Christmas had been cold and dark, and temperatures over the New Year dipped as low as minus 5 degrees Fahrenheit. Connell, with a population of about 5,000, is on the eastern edge of the Yakima Valley, and its primary industries are food processing, agricultural chemicals — and Coyote Ridge.

It’s a land of extremes: Hot, dry summers turn the surrounding land into rolling brown fields interspersed with sagebrush. In the winter, the landscape lies bare. Inside the prison, the state’s largest by population, the compound is a study in gray, all concrete buildings and large steel doors set amid acres of asphalt.

The new, highly contagious COVID-19 variant omicron arrived at the end of 2021, just as winter was starting, edging out the previously dominant delta variant in a matter of weeks. Washington had already been battered by a steady stream of natural disasters, each one made significantly worse by climate change: historic heat waves, atmospheric rivers of rain, record-breaking cold snaps. It was the official start of “COVID season,” a physician declared on a local Seattle news station.

For the 1,800 people incarcerated at Coyote Ridge, it would turn out to be the worst COVID season yet. At Christmas, there were no confirmed COVID cases among incarcerated people at the facility. Four weeks later, there were 410 new cases.

“We should be treated with the same respect and dignity as anyone in a long term mental health institution or assisted living facility. I’ve made mistakes, but I’m still human.”

Hall and a half-dozen other men tested positive. He was transferred without any of his belongings to a unit that had been empty for months and lacked heat. “We didn’t have none of our medication (or) commissary,” Hall said. “And they put us in this unit where it was so cold, we had to leave the doors open to the cells all night long.”

Meals were pushed into the unit on a cart and left there. Sick with COVID and without any heat, while outside the temperature dipped into the mid-20s, the men were left with no access to medicine, not even basic pain relievers and fever reducers. Four days passed before maintenance came and turned on the heat, Hall said, and by the time he finally got his first dose of ibuprofen — more than a week later — he was basically recovered. But for the rest of the prison population, the season was just beginning.

Imagine the worst possible place for contracting a highly contagious viral disease, and you’d have a prison: a closed, overcrowded concrete structure with poor ventilation, inconsistent access to hand-washing and sanitation, and a population disproportionately made up of what the Centers for Disease Control defines as a vulnerable demographic. Statewide, by the end of January, almost 5,000 incarcerated people out of a total population of just over 12,000 had tested positive.

Experts say the outbreak was a preview of what we can expect in a steadily warming world. “The future will not only be hotter, but also sicker,” said Greg Albery, an infectious disease ecologist who studies how climate change intersects with diseases passed from animals to humans — the primary source of most pandemics. Not only are animals getting sicker as temperatures rise and environments degrade, but as humans encroach on wildlife habitat, encounters with wild animals are becoming more frequent. “Infectious diseases are going to be increasingly a part of everyday life, and that’s coming from the climate change angle.”

THE THING that Frank Lazcano, a 35-year-old man incarcerated at Airway Heights Corrections Center, which is near Spokane, most associates with springtime at the prison is water. Located amid wetlands and along a migratory bird path, the compound is crisscrossed with ditches and culverts that drain the water from rain or that seeps up from springs. Except in the summer, there is always some water in them, Lazcano said. Rabbits and marmots occasionally make warrens in the culvert tubes, and flower gardens line the buildings. There’s a small vegetable garden and beekeeping boxes that can be seen from the recreation yard. Starting in spring, frogs begin to croak, creating a cacophony that doesn’t end until fall. It’s only drowned out by the earsplitting sound of jets from nearby Fairchild Air Force Base, located barely a stone’s throw away. Aircraft ranging from fighter jets to Apache helicopters and huge cargo carriers circle continuously overhead, tainting the air with the smell of jet fuel and poisoning the ground with PFAS, the notorious “forever chemicals.” In 2017, testing confirmed that groundwater used by the prison had been contaminated by firefighting foam, which also contains the highly carcinogenic chemicals. The Department of Corrections is now suing the air base for millions of dollars.

Springtime also means flooding, Lazcano said. The culverts regularly overflow, often forcing the closure of the yard. To check for leaks in the water pipes that run the building’s HVAC system, maintenance will occasionally dye the water green, says Lazcano. There are so many leaks in the antiquated pipes that it turns the water in the ditches the same bright green. Many of the roofs also leak — in the gymnasium, the education rooms, the libraries, the medical areas and the main visiting rooms. This leads to collapsing ceiling tiles and frequent closure of the gym, weight room and yard. Lazcano worries about the long-term consequences of all of this. The poor environmental conditions affect everyone, he said, both physically and mentally, but getting any kind of medical care can take months, and misdiagnoses are common. “We are stuck here breathing jet exhaust and drinking contaminated water with the lowest standard of medical care,” he wrote to HCN and Type. “We should be treated with the same respect and dignity as anyone in a long term mental health institution or assisted living facility. I’ve made mistakes, but I’m still human.”

Airway Heights is one of many prisons with significant infrastructure challenges. The Washington DOC is responsible for more than $3 billion in state assets, mainly prisons. According to the 2023-2033 Ten-Year Capital Plan, 158 of the 798 DOC buildings are in what the department deems “critical condition,” with an estimated $495 million in deferred maintenance. When asked about the conditions detailed in the report, a DOC spokesperson suggested they posed little risk. “While DOC has a significant maintenance backlog, we do not believe incarcerated individuals are placed in harm’s way as a result of infrastructure challenges,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “The agency makes every effort to find temporary solutions while we await funding to permanently fix problems.”

But the 630-page document painted a far more dire picture of a prison system struggling under a growing backlog of needed repairs. Deteriorating pipes cause heavy metals to leach into drinking water, fire alarms are in urgent need of updating, HVAC systems frequently don’t work. A roof replacement request for Unit 8 in the East Complex at the Washington State Penitentiary, for example, notes that “the rooftop has failed, causing water infiltration and damage to infrastructure of the building beneath the roof, saturating insulation, and other materials inside the building and causing the structure below to rust and deteriorate, which creates life safety concerns for staff and incarcerated individuals in this building.”

“We are stuck here breathing jet exhaust and drinking contaminated water with the lowest standard of medical care.”

At the Twin Rivers Unit and the Special Offenders Unit at the Monroe Correctional Complex, “The existing plumbing is in such terrible condition that the cells at the end of the heating loops in these living units remain unheated,” the DOC wrote, requesting $50 million for repairs. If the HVAC systems are not repaired, “the equipment could fail completely, leaving a building(s) without heating or cooling. … DOC does not have the operational capacity at this time that can be used in the event of a large-scale failure.”

According to the Climate Impacts Group’s studies, Washington is on track to see a 67% increase in days with temperatures above 90 degrees Fahrenheit by the 2030s. Without access to air conditioning, extreme heat in prisons could be dangerous and even life-threatening.

SUMMER ON THE COAST of Washington got off to a slow start in June 2022, but by the end of July, Seattle was setting a new record for the longest heat wave in its history, logging its sixth consecutive day of temperatures in the 90s. On July 29, when a heat wave in the Pacific Northwest left 11 million people under excessive heat warnings and another 12 million under heat advisories, Todd Bass, a formerly incarcerated person at Cedar Creek Corrections Center just west of Tacoma, filed a grievance.

“I battle dehydration and heat exhaustion,” he wrote. “The living conditions in my unit when returning from work are unsafe due to oppressive heat.”

Bass works as a wildland firefighter during the summer. He had been out that day and the days before it, digging firelines and fire trenches with his 10-man crew in grueling heat for over 14 hours a day, only to return to his cell on the second floor of Cedar Creek, which lacked air conditioning and airflow, and where the heat never subsided.

“It stays 90-100 degrees into the evening,” he told HCN and Type. “For normal people that aren’t working all day in the heat and smoke it is already bad. But for those of us trying to perform and stay safe, it is too much.”

Like many Western states, Washington relies heavily on its incarcerated population to fight forest fires, deploying around 300 incarcerated firefighters every year. But the combination of larger, more frequent and more intense wildfires and steadily rising average temperatures is putting wildland firefighters at increased risk. Extended exposure to heat can impair physical and cognitive processes, as well as increase the risk of injury. Adequate rest, hydration and cooling are essential for people recovering from strenuous outdoor exertion, and air conditioning is the most effective way to cool indoor temperatures enough to allow for adequate sleep and recovery, especially when nighttime temperatures are high, Jeremy Hess, an emergency physician who studies health systems and climate change, said.

In addition to the $800 million capital preservation request, the DOC is also requesting $10 million to add cooling capacity to housing units in the prisons that pose the greatest threat of heat illness for the incarcerated population, DOC staff and visitors. Cedar Creek is not on the list.

“If no action is taken, and in consideration of accepted climate change effects, incarcerated individuals under the care and custody of DOC will be at risk of heat-related illness in housing units that cannot maintain safe living conditions under the accepted threshold of 80 degrees Fahrenheit during extreme heat wave events,” the report said.

But even if enough funding is available, outdated electrical and plumbing systems will make it difficult to install air conditioning at many of the prisons.

Citing HCN and Type’s investigation last year into the 2021 heat wave and its impacts on incarcerated people, the former U.S. State Attorney for the Western District of Washington requested information from the DOC in June 2022 on how it was planning to deal with future heat waves.

Sean Murphy, the deputy secretary at DOC, sent an email to members of the department’s Executive Strategy Team and other administrators in July 2022, requesting information on HVAC capacity and costs. “We need to know costs of renting self-contained units, buying self-contained units, and the overall costs for a significant capital expenditure to install air conditioning within the existing units,” he wrote. “We also need to know if the power at each of the priority facilities can handle the load of temporary units.”

HCN and Type obtained a list of those results through a public records request. It showed that eight out of 12 correctional facilities would not be able to support the electrical load needed for temporary air conditioners during a heat wave, or did not know whether they could support it, or else had structural issues that would impede installing temporary AC.

Given the problems caused by the rising heat, inadequate AC and limited help from higher-ups, staff turn to the tools most readily available in prisons: punitive measures.

Washington is on track to see a 67% increase in days with temperatures above 90 degrees Fahrenheit by the 2030s.

On the other side of the Cascades from Cedar Creek, temperatures around Spokane were also rising, sliding into the triple digits by July 27 and hovering around there for five days. Almost immediately, a steady stream of grievances poured in. But rather than focusing on the extreme temperatures or lack of AC, incarcerated people complained about the loss of the one thing that, after months of lockdowns and quarantines, had kept many of them sane: Access to the yard and to recreation.

Gary King, who is incarcerated at Airway Heights, wrote, “AHCC is using heat advisory to not give and let (incarcerated individuals) have recreation. According to AHCC, they plan on taking (incarcerated individuals’) recreation the whole summer. That’s ridiculous.”

Without access to the yard, which had already been restricted because of COVID-19, incarcerated people were effectively forced to either sit in their cells or hang out in the dayroom, where they had to stay seated; standing, walking laps and other physical activities were not allowed in his particular unit, Thomus Manos, an incarcerated man at Airway Heights, wrote. Researchers have shown that prolonged exposure to heat increases aggression and lowers cognitive ability; in the long term, it increases the risk of metabolic diseases like diabetes and high cholesterol, as well as heart attacks and stroke. But the same thing holds true for lack of exercise, which can cause obesity, metabolic and cardiac diseases. The combination is a health disaster.

According to emails obtained through a public records request regarding managerial responses to extreme heat over the summer, HVAC malfunctions at prisons like Monroe caused the library to become unbearably hot. It was shut down, and the rooms used for mental health services had to go without cooling for at least 20 days, effectively punishing people because there was no way to regulate the increasingly extreme indoor temperatures.

The increased use of punitive measures to deal with public health and environmental conditions is not new. But it skyrocketed nationwide during the pandemic, causing extensive psychological harm to the incarcerated population. In September 2022, Karen Endnote, who is currently incarcerated at Mission Creek Corrections Center for Women, caught COVID for the second time. She was transferred to the larger women’s prison in Gray Harbor and put in solitary confinement.

For one week, Endnote was locked in an 8-by-10-foot room with a toilet, a sink and a concrete slab with a thin mattress. Glaring overhead lights were left on 24 hours a day, and her food was shoved into the room through a slit carved out of the thick steel door. Trash piled up around her room, and she lost her phone privileges. “We were sick!” she recalled. “We were sick, and they treated us like utter crap.” She was too sick to eat and had to be put on a liquid diet. The entire time she was there, she was only allowed to take one shower. “It was punishment, that’s what it felt like,” she said. “That we were getting punished cause we were sick.”

It was the first and only time Endnote had ever been in solitary, a practice the United Nations special rapporteur has deemed tantamount to torture. This year, she caught COVID again. At least she is pretty sure she did; she chose to not get tested. “I wasn’t going to take that chance again,” she said.

The fight to end solitary confinement has been going on for decades, and it had made steady progress before the pandemic. The ACLU declared 2019 a watershed moment for ending the practice after 28 states introduced legislation to ban or restrict solitary confinement and 12 states passed reforms. And then prisons were struck, unprepared, by a major public health crisis. In October 2021, original research released by the Marshall Project and Solitary Watch showed that solitary confinement increased across the country during the pandemic, from roughly 50,000 people to nearly 300,000 on any given day, with current rates still 2.5 times higher than pre-pandemic levels.

According to the DOC, “Secretary (Cheryl) Strange has committed to drastically reducing the use of solitary confinement at all of our facilities over the next five years. We have spent the past few months working with industry experts and consultants on a comprehensive plan to achieve that goal without compromising the safety of staff or incarcerated individuals. The plan is being finalized and we expect to release it in the near future.”

COVID-19 quarantines normalized solitary confinement, Jessica Sandoval, the national director of Unlock the Box, told HCN and Type. Now prisons are reaching for punitive measures like lockdowns and other restrictions to deal with climate disasters. “If the only tool they have is a hammer, everything is seen as a nail,” she said. “In this case and so many other cases, that’s their tool.”

THE MONROE CORRECTIONS Complex, a campus comprising five prison units, sits in a fertile valley, flanked by the sprawling Skykomish River on one side and white-capped mountains in the background. The imposing brick administrative building at the entrance, adorned with colonial-style pillars, bright green grass and towering trees, paints a peaceful picture. But behind the brick lie gun towers and forbidding walls. One of the prisons is over a century old. It leaks when it rains and traps heat and humidity. Mold spreads, leaving black blotches on the walls and floors. Now wildfires are adding another health hazard to the mix.

Atif Rafay has been incarcerated in Washington since 2004 and is currently in Twin Rivers Unit. “I didn’t notice the smoke as much in the 2000s or early 2010s, even,” he told HCN and Type over the phone. “But now, every year about the same time, at the end of summer when stuff is heated up and dried out, the wildfires start.”Since 2012, wildfires and smoke season have become an unofficial part of the Seattle area’s calendar. The fires went from burning tens of thousands of acres in 2011 to hundreds of thousands in 2012. Every year since then, more than 150,000 acres have burned, according to Thomas Kyle-Milward, who each year tabulates fire statistics across the various state and federal agencies involved in wildfire management.

Last September, smoke from the Bolt Creek Fire near Skykomish added to the layer of haze from the fires burning farther north into Canada. “Seattle smoke season is here,” Capital Hills Seattle Blog declared.

“The sky was incredible,” Rafay remembered. The air glowed orange and sunsets were a bright fuchsia. “You could not leave your windows open because of the smoke.” He recalled walking from his unit outside to the chow hall and watching ash from the wildfires fall onto his shoulders.

Every year about the same time, at the end of summer when stuff is heated up and dried out, the wildfires start.

The face masks he’d seen as useless against COVID-19 suddenly became useful, shielding them from the fine particulates that come from burning forests and further damage lungs. For Rafay, this was important. One study examining the correlation between increased particulate matter from West Coast wildfires in 2020 and COVID-19 cases found that wildfires significantly increased illnesses and deaths, up to four weeks after the exposure.

Rafay’s lungs were already damaged from a bad case of pneumonia in 2019, which was misdiagnosed by prison nurses for days. More than a year later, he got COVID-19. He was placed in one of the military-style tents set up on the grounds, a Rapid Deployment Care Facility (RDCF) that patients jokingly renamed the “Really Don’t Care Facility.”

He remembered being sick and yet obliged to help four other men carry a heavy hospital bed from one dormitory tent to another because the roof was collapsing under the weight of the snow. Perhaps afraid of catching the virus, the staff left baby monitoring alarms to keep track of the patients from a distance, effectively leaving the sick men on their own. “That experience was the craziest thing I have ever seen,” Rafay said.

He noted that the systemic tendency continues to be toward less, not more, freedom for incarcerated people. During wildfires, prison administrators will cancel outdoor privileges and gym access and keep everyone cooped up inside, Rafay told Type and HCN. You can’t go outdoors because of the smoke, he said, but staying inside means everyone is confined to their cells or the day room.

While the main threat fires pose comes from poor air quality, the fires themselves are becoming more dangerous. Last year, incarcerated people at the Larch Corrections Center in Clark County were evacuated when the nearby Nakia Creek Fire expanded in size. Scientists predict that not only will the fire season become longer, the area burned by wildfires in Washington is expected to double by the 2040s, and triple by the 2080s.

And these climate hazards aren’t happening in isolation. “The challenges as we move forward — and by this I mean a decade or two — is it’s not just going to be a heat wave — it’s going to be a heat wave combined with a nearby fire combined with blackouts combined with displaced populations,” Hess, the emergency physician, said. “I don’t want to be just pointing to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse all the time, but it’s the reality of it. We’re going to be dealing with these multi-system stressors, and they may well overwhelm our capacity in certain instances.”

Image: Cristiana Couceiro/High Country News

WHEN THE PANDEMIC first hit the United States in 2020, Seattle was ground zero. A man who had recently traveled to Wuhan fell sick, and communal spaces followed soon after: senior homes, food-processing factories — and prisons. In March 2020, Columbia Legal Services filed a petition on behalf of five incarcerated people, including a pregnant 21-year-old. “When we were staring down the face of this potentially very deadly virus, we just felt like the state had an obligation to be as proactive as possible in trying to keep folks in custody safe,” Laurel Jones, assistant deputy director of advocacy at Columbia Legal Services, told HCN and Type over the phone. The petition asked the Washington Supreme Court to intervene in the health crisis by releasing incarcerated people, especially those who were older, had underlying health conditions, or were already close to their release date. “This is not something where we’re talking about just opening the jailhouse doors and letting everybody out without any sort of precautions being taken,” Jones said. “But also: The vast majority of people in prisons are not there to serve a life sentence and they don’t deserve to die in prison.”

The petition failed, but eventually the state Supreme Court ordered the governor and the DOC to take all necessary steps to protect the health and safety of incarcerated people in response to the Covid-19 outbreak. In response, Gov. Jay Inslee commuted the sentences of around 1,000 people as part of a larger trend that saw around 37,700 people released early from prisons around the country. This was the state’s first large-scale experiment with decarceration.

Scientists predict that not only will the fire season become longer, it’s expected to double by the 2040s, and triple by the 2080s.

While decarceration has long been a politically divisive topic, during the pandemic, it was deemed one of the most effective ways to keep people safe. For a growing number of researchers, the same applies to combating climate change. “Part of the strategy for keeping people safe (from climate hazards) has to be decarceration,” Jasmine Heiss, a criminal justice expert who formerly worked as a program director at the the Vera Institute of Justice, told HCN and Type. “Ending mass incarceration has always been an urgent problem. In the light of the climate crisis even more so.”

Locked away in rural communities with decaying infrastructure and inadequate resources to protect themselves during extreme weather events or public health crises, incarcerated people are completely dependent on the decisions — and the whims — of the prison bureaucracy.

“The first thing many of us wonder when natural disasters happen now is whether or not anyone made a plan to keep incarcerated people, people on some form of supervision, safe? Are they literally trapped, or is there a real safety plan?” said Heiss. “I think the fact that so many people are concerned, are nervous, speaks to the infrequency with which a plan is articulated — or even created — beforehand.”

When asked about emergency management plans for climate hazards, the DOC responded that “while security concerns prevent us from disclosing the specifics of emergency evacuation plans, each of our prisons, as well as our field offices and reentry centers, is required to have one. … In addition to wildfires, DOC has plans in place to respond to floods, windstorms, earthquakes and hazardous materials.”

HCN and Type reviewed DOC plans for dealing with extreme heat, obtained through department requests. The incident action plan largely deals with the chain of command during a heat event. There is a brief section on keeping incarcerated people safe, with suggestions like putting fans in living units and opening doors. The two-page heat mitigation plan also advises providing sunscreen, allowing incarcerated people to take clear cups outside and, if it’s above 89 degrees, letting them wear shorts, T-shirts and shower shoes without socks outside.

Washington is largely seen as a progressive state on climate, with “one of the more progressive frameworks to address environmental justice in the U.S.,” according to legal experts at Law360, but prisons are absent from the state’s climate adaptation plans. Last year, the DOC requested funds from the Legislature to hire a consultant to develop a DOC Climate Change Impact Mitigation and Resilience Plan, but were denied. When asked about climate plans for incarcerated people and prisons, the governor’s office mentioned the work the DOC has been doing to mitigate the impacts of extreme heat events in prisons, citing a one-page pdf and adding that it was a “relevant policy discussion to have.” A law was passed earlier this year to update the state’s climate response strategy, but it did not specifically mention incarcerated people, nor is the Department of Corrections one of the agencies involved in its creation, although a Washington Department of Ecology spokesperson said, “There may be opportunities for that agency to engage in the planning process.”

This year, a University of Washington Climate Impacts Group report on extreme heat in the state singled out incarcerated people as a high-risk population. The group, which has worked with several other state agencies to help develop agency-wide climate adaptation plans, told HCN and Type that it would be happy to support DOC efforts to develop a climate adaptation plan but that it has not yet been approached.

A small but growing number of studies show that incarceration and climate disaster susceptibility often overlap, that failing to update prison infrastructure “will be catastrophic.”

Scientists have called climate change the “biggest threat modern humans have ever faced,” yet scant literature exists on how it will impact incarcerated people. A small but growing number of studies show that incarceration and climate disaster susceptibility often overlap, and that failing to update prison infrastructure “will be catastrophic,” with increasingly negative health and legal implications for incarcerated people and correctional agencies. Many studies also point out the glaring overlap between climate change and mass incarceration: Both affect BIPOC people and communities at much higher rates, stemming from systematic neglect of investment in those communities and in many cases, direct policies that have increased incarceration rates and climate vulnerability. Seen from that perspective, decarceration is a form of climate justice. From a scientific, legal and public health perspective, it is a necessary way of dealing with climate challenges ahead.

Washington state is already taking tentative steps in that direction. Until recently, incarceration in Washington state had been trending upwards, peaking in 2018, when the prison population in the state topped 18,000. The rise can be traced to harsh sentencing rules and sentence lengths from the “war on drugs’’ and “tough on crime” narrative of the ’80s and ’90s, said Christie Hedman, executive director of the Washington Defenders Association, a resource center for public defenders. The year 2020 was the first time in almost two decades that Washington’s incarcerated population dipped below 16,000. Now it is hovering at around 13,000. Only 70% of prison beds are occupied, and this year the DOC announced the closure of Larch Corrections Center, citing, among other things, the falling incarceration rate, though critics say that basic budgetary concerns might also be involved.

When asked for comment, the governor’s office replied that “Gov. Inslee has sought to create a more humane corrections system that focuses on rehabilitation rather than punishment, and the State has made strides toward achieving that goal. We are committed to reducing recidivism by supporting innovative programs that provide incarcerated individuals with the tools they need to be successful when they reenter the community.”

Most of the recent decrease in incarceration rates stems from COVID-19, said Hedman. The pandemic shut down courts, reduced mobility and created a backlog of cases, so at least some of the decrease is temporary. There have also been more long-lasting changes. Advocates, incarcerated people and some legislators have fought to pass key reforms that should reduce the number of people in prison. Washington has now passed several laws that would reduce incarceration rates, such as a bill that eliminates the practice of using prior juvenile adjudications in adult sentencing. Still, many of these laws will only kick in for future defendants and do not apply retroactively, so they will not reduce the current prison population. The most significant retroactive policy was the 2021 state Supreme Court decision that found the state’s ban on simple drug possession to be unconstitutional. That decision made more than 1,000 people eligible for release, and hundreds more are eligible for resentencing.

Hedman and other advocates we spoke to see these advances as just a small step to a much larger change that needs to happen. “I think that we really, as a society, need to look at what our definition of public safety is and who are the communities that we’re trying to protect,” she said. “We need to be willing to take some bold steps to look at shortening sentences, with the idea of really trying to focus on rehabilitation and support funding for things that stop bringing people into the system.”

At the end of 2022, winter had already gripped Mission Creek, with the rumor that a storm was approaching. The heating had failed again. But this time it wasn’t in Mission Unit; it was in Gold, a newer living unit. After a group of incarcerated women threatened to contact the media about the lack of heating, the staff brought in stadium heaters the size of jeeps, remembered Tiffany Doll, who was then incarcerated in Bear, the third unit at Mission Creek. “I don’t know why they keep these facilities open,” she told HCN and Type. “It’s 2023. Why would you subject people to this?”