On April 30, a train carrying oil from North Dakota’s Bakken formation derailed in Lynchburg, Virginia releasing close to 30,000 gallons of highly flammable crude into the James River. It was the latest accident in a string of derailments and collisions involving trains carrying Bakken crude, including last July’s fiery explosion in the eastern Quebec town of Lac-Megantic, which killed 47 people and destroyed approximately 40 buildings.

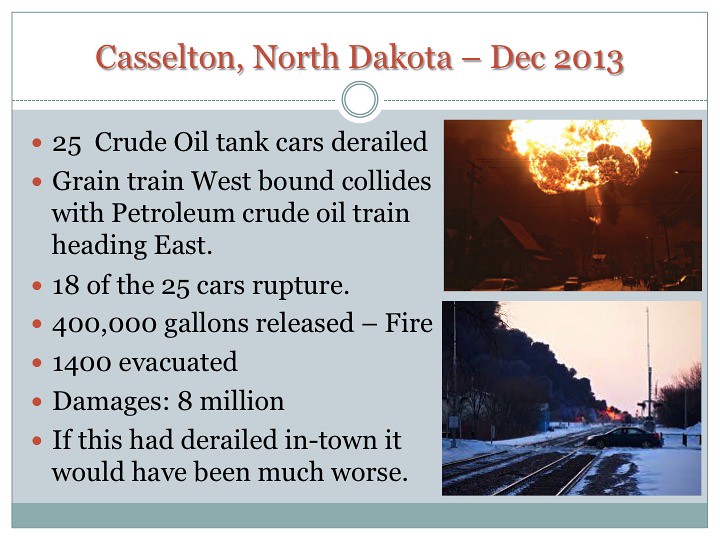

Two weeks before the Lynchburg derailment, the Virginia Department of Emergency Management provided a power point presentation on oil by rail transport to the city‘s local emergency planning commission. It included an overview of the three major accidents that occurred last year, including the slide pictured here, but didn‘t mention how or if the railroad companies will share information with local municipalities.

Two weeks before the Lynchburg derailment, the Virginia Department of Emergency Management provided a power point presentation on oil by rail transport to the city‘s local emergency planning commission. It included an overview of the three major accidents that occurred last year, including the slide pictured here, but didn‘t mention how or if the railroad companies will share information with local municipalities.

The city of Lynchburg was spared the kind of destruction visited upon Lac-Megantic because only one of the 16 cars that derailed was breached. Three cars, including the one that ruptured, rolled down a steep embankment into the river, sending flames and thick black smoke into the sky. “We’re lucky the cars rolled into the river and not on land,” says Lynchburg City Manager Kimball Payne.

Payne was in City Hall when the accident happened. There were people running up and down the halls, he says. When he looked out the window he saw a huge cloud of black smoke emanating from what appeared to be the center of town. “I was convinced people were dead,” says Payne.

Pat Calvert of the James River Association, a conservation group, says the train derailed very close to a popular fishing spot and city park. Much of the track also follows the James River Heritage Trail, popular among joggers and bikers. Calvert says that due to heavy rains during the two days preceding the accident very few people were out. In addition there was construction activity in the park, which was closed. “If it had not been raining for two days there would have been joggers and bikers directly alongside where it occurred,” says Calvert.

Payne says he had not received any information about the shipment of Bakken crude through Lynchburg, though he wasn’t surprised about it. He admits that until the accident he had never really considered the risks involved.

Two weeks before the Lynchburg derailment, the Virginia Department of Emergency Management provided a power point presentation on oil by rail transport to the city’s local emergency planning commission. According to William Aldrich, the director of the city’s emergency services, it was the first time that Bakken crude was discussed. The power point presentation, obtained by Earth Island Journal, includes general background on the characteristics of Bakken crude as well as an overview of the three major accidents that occurred last year in Lac-Megantic, Alabama, and North Dakota. The presentation does not include any mention of how or if the railroad companies will share information with local municipalities.

“It would be very reasonable for a community like ours to have an understanding of what sorts of substances are coming through annually or maybe even more frequently,” says Payne. “We’d like to know in general how much and how frequently these materials are moving through our community and what hazards does it pose.”

Yet, as a recent Earth Island Journal investigation found (read, “Warning, Highly Flammable“), despite the rapidly growing business of shipping crude by rail across North America, the railroad industry has been slow to provide even rudimentary information to local officials and emergency responders about shipments of Bakken crude.

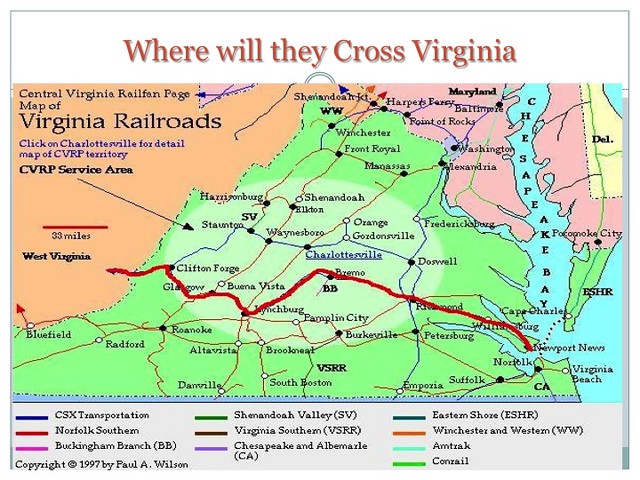

Gary Roakes, the fire marshal of Amherst County, VA, which borders the city of Lynchburg, wrote: “We have not had any contact with CSX [whose train derailed on April 30] or any other carrier about what is being shipped through this area.” According to Brett Burdick, deputy state coordinator at the Virginia Department of Emergency Management, about four oil trains a week are now moving through Lynchburg and that number is likely to increase. Most of those trains are headed to the Delaware City Refining Company in Newcastle County.

One week after the Lynchburg derailment the federal Department of Transportation issued an emergency order requiring rail freight carriers notify emergency first-responders along routes being used to move Bakken crude oil.

The federal government is finally waking up to this new safety threat. One week after the Lynchburg derailment the federal Department of Transportation issued anemergency order requiring railroads operating trains containing more than 1,000,000 gallons of Bakken crude, or about 35 tank cars, to provide information about frequency, volume, and routing to State Emergency Response Commissions (SERC). The railroads have 30 days to comply with the new regulation and failure to do so will bar them from transporting Bakken crude in large quantities.

According to the DOT, the shipment of Bakken crude throughout North America and Canada poses an “imminent hazard.” The emergency order states: “The number and type of petroleum crude oil accidents…that have occurred during the last year is startling, and the quantity of petroleum crude oil spilled as a result of those accidents is voluminous.” Indeed last year more oil spilled in rail accidents — 1.15 million gallons — than the previous 35 years combined.

Despite the new rule, emergency response commissioners of several states interviewed by Earth Island Journal have had little contact with the railroad companies about the logistics of shipping Bakken crude.

“At this point the railroads have not reached out or sent any information,” says Kevin Wilson, a spokesman for the Delaware Emergency Management Agency. Wilson, who says the state has a good working relationship with the industry, expects the companies, CSX and Norfolk Southern, to present information at the next SERC meeting in early June, just days before the federal order goes into effect.

Brett Burdick of the Virginia Department of Emergency Management, who is overseeing implementation of the new order, says the goal is to notify local governments and make sure they’re aware of the frequency and volume of Bakken crude shipments. “Local governments have a right to know,” he says. “We as an agency have moved forward proactively to brief local governments along the shipping line,” he added.

In New Jersey, a recent report on oil by rail transport in the local daily, The Record says that, “The rapid increase in activity has gone largely unnoticed, even though the trains are moving through densely populated towns, passing within a dozen feet of schools and homes, and crossing environmentally sensitive areas like the Oradell Reservoir.”

Mary Goepfert, external affairs officer in New Jersey’s Office of Emergency Management, says the new DOT order is on the agenda for the state’s upcoming SERC meeting. She says the state has dealt with storage and movement of extremely hazardous materials in the past so the question is whether they need to do anything differently and if there are additional training requirements. “When you have any type of threat, whether a hurricane, a civil matter or Bakken crude, any knowledge that you have of that threat is important because when you have knowledge you can take steps to mitigate it,” says Goepfert.

In a written response to questions for my earlier Earth Island Journal story on this issue, CSX, which operated the train that derailed in Lynchburg, said that the company works with emergency responders “across its network” to make sure they “have access to information about materials moving on the rail network should the need arise.” In addition CSX shares information through a program called SecureNOW, which gives “security officials and first responders the ability to track, in nearly real time, the location of CSX trains and their contents.” CSX says that SecureNOW is used in nearly every state in which CSX operates, “including along the company’s major crude oil routes to the Northeast refineries and Virginia.”

Yet an analysis of one such agreement between the state of Pennsylvania and CSX suggests that access to SecureNOW provides only limited information about frequency and volume of hazardous materials shipments. In February, CSX and the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA) signed an agreement giving PEMA access to NOW, or the “Network Operations Workstation.” The agreement (see pdf here) is known as a train information access arrangement (TIAA). According to the agreement, “Authorized PEMA personnel will be given access via the Internet to CSXT’s NOW external-use version.” However the agreement precludes employees with access to the network from using it for planning purposes. “Information available from NOW shall not be used to respond to inquiries not related to a threat, actual incident or accident such as those contemplated above. PEMA shall refer such other inquiries to CSXT for response,” the agreement states.

PEMA press secretary Cory Angell says that the state is “only allowed to disseminate or access information under an emergency situation.” The agency is working on a similar agreement with Norfolk Southern.

Though available online, the CSX Memorandum of Agreement discourages PEMA from publicizing the partnership. The agreement includes a clause, which states that, “neither Party shall make any media releases or formal public announcements or formal disclosures relating to the TIAA unless the other Party provides express written consent thereto.”

An air of secrecy has surrounded the booming oil by rail industry since last year’s devastating accident in Lac-Megantic. Since then trains carrying Bakken crude have derailed in Alabama, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and now Lynchburg. No new regulations, other than the DOT’s recent emergency order, have been issued. The industry continues to argue that oil from the Bakken formation is no more dangerous than other forms of crude.

Meanwhile the trains continue to roll through towns and cities throughout North America. Two weeks ago, Central Maine and Quebec Railway, the new owner of the railway that runs through Lac-Megantic announced that they plan to resume shipments of crude oil in the next 18 months. In Lynchburg, city manager Payne says he saw a crude oil train go through the city two weeks after the derailment. the night before I spoke with him. After the accident it took just a couple of days to install new rail and ballast, he says. Though environmental remediation continues the tracks are spic and span. “It’s like it never happened,” he says.

This post originally appeared at Earth Island Journal and is posted here with permission.