EPA staffers are spending their days addressing an industry wish list of changes to environmental law, according to Elizabeth

Southerland, a former senior agency official who issued a scathing public farewell message when she ended her 30-year career there on Monday.

Southerland, who most recently served as director of science and technology in the EPA’s Office of Water, said that agency staffers were now devoted to regulatory rollback based on the requests from industry. Companies and trade groups have directly asked EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt for some changes. Other requests have come in through public comments in response to executive order 13777, which the White House issued in February. That executive order directed federal agencies including the EPA to suggest regulations to be changed, repealed, or replaced.

The overwhelming majority of the more than 467,000 public responses to the EPA about the executive order urged the agency not to roll back environmental regulations. “I am a PhD chemist, recently retired after more than 35 years of industrial research in material science and chemistry. I am also old enough to remember life before the EPA,” read a typical comment submitted in May. “Do not take us back to those times!”

But Southerland said that a working group headed by EPA Associate Administrator Samantha Dravis and the agency’s chief of staff, Ryan Jackson — both of whom were appointed by Scott Pruitt — cherry-picked industry comments calling for rollback and submitted them to scientists and other career employees at the agency.

“They pulled out the ones from the industry — the coal, electric power, oil and natural gas areas, just them — and sent them around and asked us to respond within one day about whether we agreed with the request for a repeal,” said Southerland.

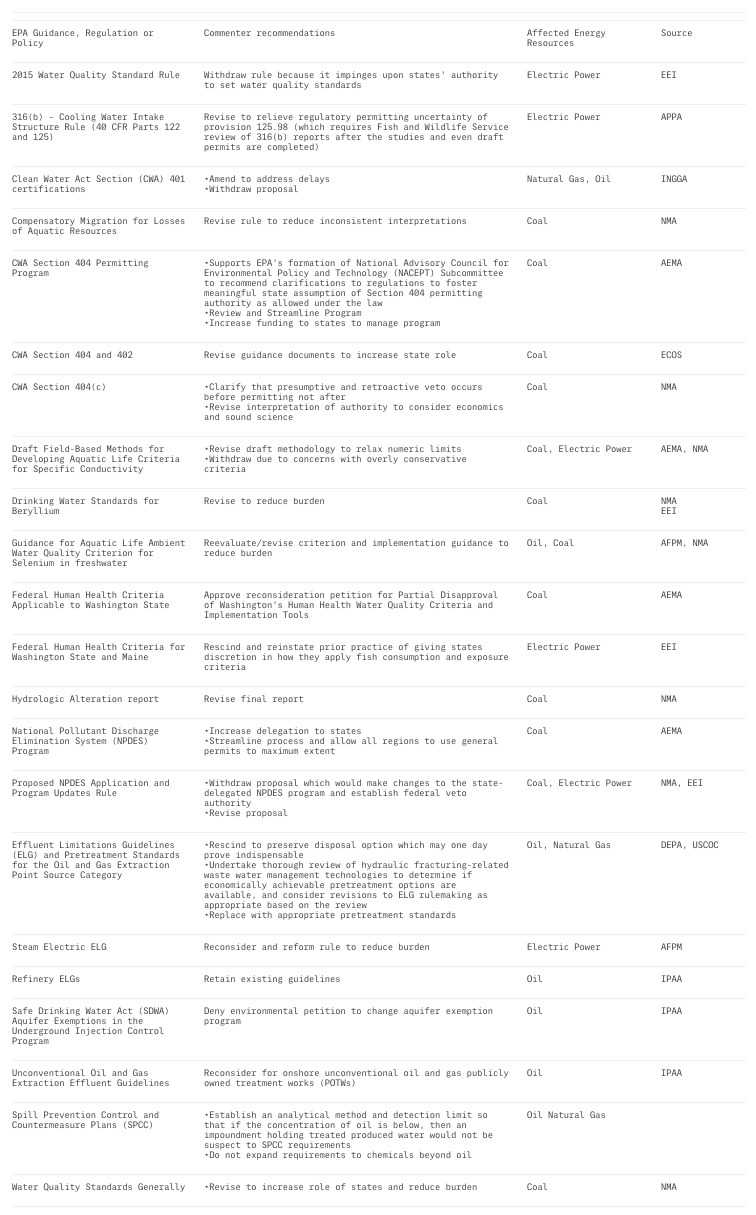

An internal agency spreadsheet obtained by The Intercept supports Southerland’s account of the EPA’s efforts to prioritize the energy industry’s requests. The document appears to be a response of industry and government groups to executive order 13777 and details the desires of organizations representing electric power, natural gas, oil, and coal to revise, amend, withdraw, or otherwise change more than 20 environmental regulations in various ways.

One entry notes that the American Public Power Association asked the EPA to revise the Section 316B Cooling Water Intake Structure Rule. The rule, which was finalized in 2014 after 20 years of scientific work and litigation, requires power companies to minimize the damage to aquatic animals when they intake water to cool engines in their plants. The APPA’s comments, accessible on regulations.gov, describe the rule as “cumbersome” and ask that it be revised.

Another regulation that the document shows the EPA to be reconsidering at the behest of industry is Section 401 of the Clean Water Act, which gives states the authority to issue permits for facilities or activities that will impact local water quality. According to the undated spreadsheet, the natural gas and oil industries would be affected.

Agency staffers were also asked to withdraw the 2015 Water Quality Standards Rule, an update of the Clean Water Act that was designed to limit water pollution and protect water quality. The EPA document lists EEI as the source of that request, an apparent reference to the Edison Electric Institute, which submitted public comments in response to the executive order that describe the rule as impinging on states’ “authority to set water quality standards” and ask that it be withdrawn.

From an undated internal EPA spreadsheet detailing the requests of organizations representing electric power, natural gas, oil, and coal to roll back environmental regulations.

The EPA did not respond to a request for comment.

Southerland noted that “states would know better whether it impinges on their ability to set quality standards. But no state has asked” that it be withdrawn.

Other rules the EPA is reassessing include drinking water standards for beryllium, which would affect the coal industry, according to the spreadsheet; guidance for selenium levels in freshwater, which would impact oil and coal; the aquifer exemption under the Safe Drinking Water Act; and the National Pollution Discharge and Elimination System, which would affect the oil, coal, and electric power industries.

Although these requests came directly from industry and were delivered to staff by political appointees, Southerland said that EPA career staffers are assessing the requests on their merits. “We said, ‘No, because there’s no new science that would indicate that this report is out of date, there’s no need to change it,’ or, ‘There’s no reason to repeal this rule because there’s no new data,’” said Southerland. “Or, in the case of a regulation, we’d say, ‘We found no flaw in the process or technical basis,’ because that’s the normal way of doing things.”

Many of these EPA employees are scientists like Southerland, who holds a Ph.D. in environmental science and engineering. “They’re all super technical people,” she said. “They want to finish their careers, and in order to mentally survive this atmosphere, they have to have hope.”

Scott Pruitt began to wage war on environmental regulation as soon as he was appointed in February. Among the more than 30 rules and policies he has targeted for delays or elimination since then are the Clean Power Plan, the methane rule, the Waters of the U.S. rule, and a proposed ban of the pesticide chlorpyrifos.

Southerland clarified that this first round of regulatory rollbacks represents only a fraction of the rules the EPA staff is now being asked to evaluate. “These 30 are just the ones that the oil and gas and pesticide people asked for up front,” said Southerland, who described the companies and industry groups that requested these initial changes as having “their own special deal.”

The full range of proposed rollbacks will become apparent in September, when the EPA and other agencies are required to report back on their assessments of regulation. In the meantime, the staff of the EPA is spending their time considering how to dismantle the policies they have helped create — a process that’s both time consuming and extremely expensive.

“The taxpayers are paying for us to now spend enormous amounts of federal employee hours undoing everything they had spent those same federal employee hours building,” said Southerland. “Look at the enormous treasure that these people are having everyone expend for their ideology.”

This article first appeared at The Intercept and is published here with permission.