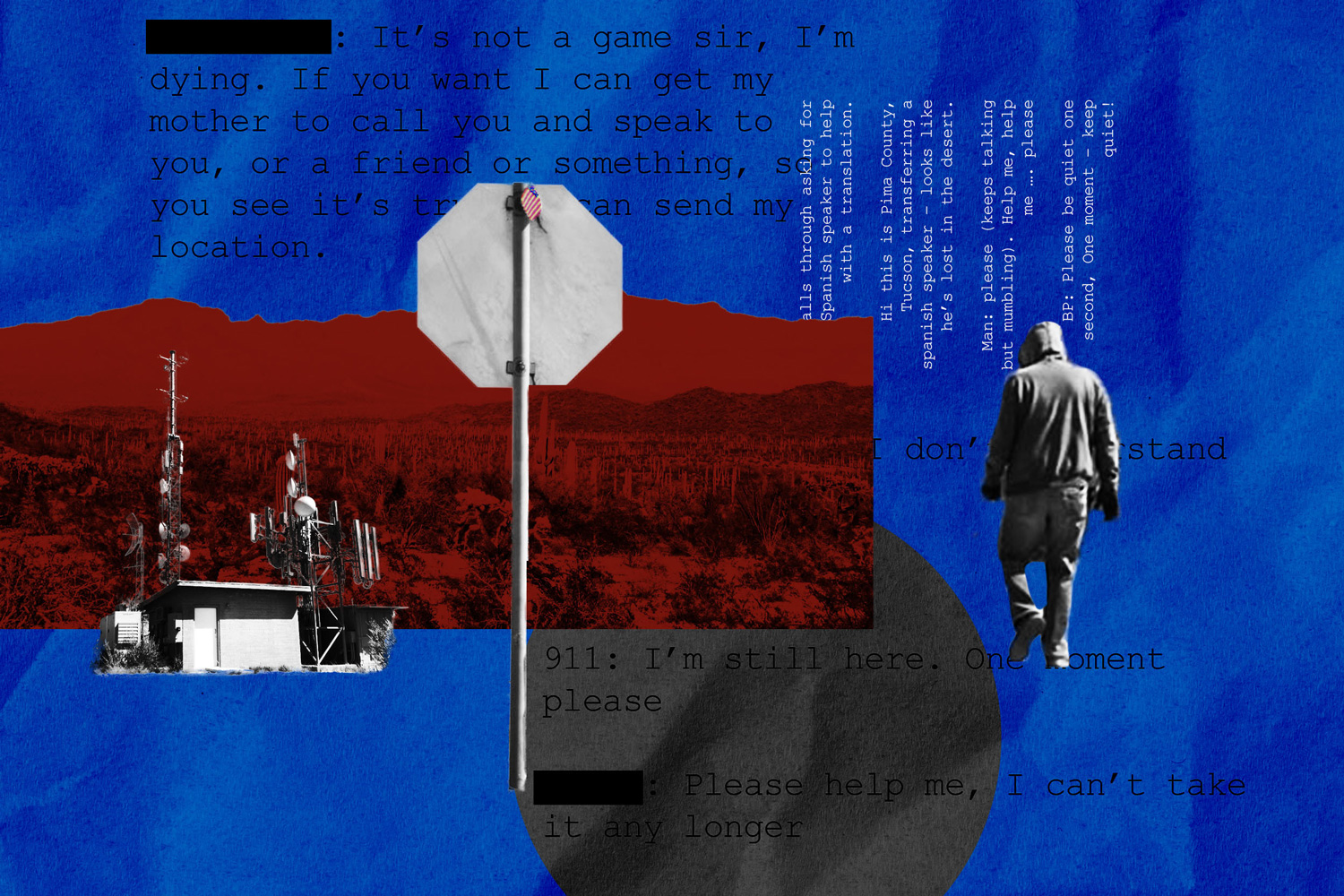

On June 27, 2022, around 1:44 a.m., a man lost in the desert outside Tucson, Arizona called 911. An emergency services dispatcher for Pima County answered. The man, clearly distressed, tried to describe his surroundings and explain that he was lost, wet and freezing. But before he could finish, the dispatcher interrupted him, saying, “I don’t understand, un momento,” and abruptly transferred the call to the U.S. Border Patrol. The agent who picked up shushed the caller as he started to speak —“Cállate!” (“Be quiet!”) — and spoke to the dispatcher instead, in English. Then they hung up, leaving the man to the agent. An incident report suggests that no actions were taken to follow up or locate the lost caller: “No additional calls have come from the subject. … At this time the caller has not been identified and not located.”

This recording is one among almost 2,500 911 calls from Pima County, Arizona, that the humanitarian group No More Deaths has obtained through public records requests and analyzed in a new report. High Country News and Type Investigations exclusively reviewed the report and some of its supporting documents. The calls provide a rare window into how local governments in the Borderlands treat migrants in distress. According to the report, 911 dispatchers in one of the country’s largest and most dangerous migration corridors often abdicate responsibility for the well-being of suspected migrants, handing them off to the Border Patrol without adequate follow up to ensure that the caller was found. In the large trove of cases analyzed, the county almost never sent out its own search-and-rescue deputies.

The calls suggest “a troubling pattern of unconstitutional and abusive practices that directly contribute to the ongoing humanitarian crisis at the border,” the report concludes.

When someone who seems to be a U.S. citizen calls 911 seeking search and rescue, dispatchers typically try to determine their location, medical state, access to food and water and the battery life of their phone while simultaneously coordinating a response with sheriff’s deputies. But No More Deaths’ analysis shows that the Pima County dispatchers did not conduct standard missing-person intakes in calls made by people they thought were undocumented. Instead, in 99% of cases, they quickly, and often without explanation, rerouted the call to the Border Patrol, an agency whose primary mandate is rounding up and deporting unauthorized migrants.

Image: Marissa Garcia/High Country News

No More Deaths argues that the county’s practice of profiling undocumented migrants and selectively involving the Border Patrol not only creates “wide disparities” in search and rescue responses, it violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law.

Pima County told HCN and Type that the Border Patrol, with its sizable surveillance resources and manpower, can tackle search-and-rescue efforts in remote areas more efficiently, even though the county dispatches its own teams to handle calls from lost hikers, tourists and others in those same regions. But in cases between 2016 and 2018 that involved possible migrants, the county’s teams were never called in — not even when the caller dialed 911 repeatedly for hours, or the Border Patrol was unable to respond.

“I found that really shocking, especially given their own justification that they transfer to Border Patrol because they respond faster and have more resources,” said Parker Deighan, a No More Deaths volunteer and co-author of the report. “Even when they clearly know that someone has not been rescued for many, many hours, and that the Border Patrol is not responding, there’s still no activation of county resources.”

No More Deaths is among several regional volunteer groups that conduct rescue expeditions and collect data on the rising death toll. The group found that in 68% of the calls analyzed for the report, dispatchers didn’t speak enough Spanish to properly communicate with callers. Yet in only in 2% of cases did non-Spanish speaking dispatchers use phone translation services. In half the calls, they didn’t explain that the caller would be transferred to the Border Patrol, leaving callers holding the phone, hearing nothing but strange dialing noises, ring tones, annoyed responses or long pauses. Sometimes, the callers panic or just hang up.

“The system is so abstracted, and one of the things we try to capture is the inhumanity of that bureaucracy,” Deighan said. “But it’s really stark, when you listen to the calls and hear the desperation they are calling with, in what might be their last moments, in the middle of incredible trauma, and they’re responded to so callously.

“These dispatchers are really just a representation of the whole system that really bureaucratizes this human tragedy.”

Cecilia Ochoa, a 911 dispatch manager for the Pima County Sheriff’s Department, said that receiving a call in Spanish would not be “the sole reason why we would send somebody over to the Border Patrol. … If they’re calling from an unpopulated area or remote area, we’re going to always transfer to the closest available resource” — the Border Patrol’s search-and-rescue unit. County officials added that most dispatchers know enough Spanish to ask if someone is lost. Getting a translator and conducting a full intake, instead of quickly transferring to the Border Patrol, would only “extend the response time,” the officials said.

Emergency services are in high demand in the Borderlands. According to the United Nations, the U.S.-Mexico border is the world’s deadliest land migration route. Between 1998 and 2020, 8,000 migrants died there, according to the Border Patrol.

“These dispatchers are really just a representation of the whole system that really bureaucratizes this human tragedy.”

Advocates and academics have long argued that U.S. policy contributes to these deaths. Since the Clinton administration, the federal government has followed a policy called “prevention through deterrence,” which involves policing heavily trafficked migration routes and forcing migrants to cross in more “hostile terrain,” putting them in “mortal danger,” as a 1994 strategic plan created by the U.S. Border Patrol put it. A 1997 federal watchdog report noted that the “deaths of aliens” could be a metric that the strategy was working.

Even so, it’s not clear that it’s made a dent in border migration. The number of people making the arduous journey has, in fact, risen greatly in recent years — and so has the migrant death toll. Meanwhile, funding for the Border Patrol increased more than tenfold between 1990 and 2021.

By law, trained medical professionals must provide emergency care to anyone who needs it. But over time, cash-strapped local emergency responders have shifted more responsibility to the Border Patrol.

Pima County officials say “it is not in policy” to ask callers about their immigration status. Instead, county officials have told humanitarian workers that they base decisions to involve the Border Patrol on geography — whether a caller is in a remote desert area, for example.

But in most of the calls sampled, dispatchers transferred to the Border Patrol quickly after the caller started speaking Spanish, even when the caller said they were near an urban area or road.

In one call transferred from another county, the Pima County dispatcher first asked: “Is (the caller) an illegal as far as you can tell?” then said, “We’re not going to deal with it.” Instead, they patched in the Border Patrol.

There are some simple solutions, Deighan said. For example, the county could hire Spanish-speaking staff and make translators available when necessary. It could also ensure that the same intake questions are asked across the board. Even given its limited resources, the county’s search-and-rescue teams could still respond should the Border Patrol defer or decline to. (The county told HCN and Type it does respond when Border Patrol cannot but did not elaborate on how often this happens.)

Ultimately, advocates envision a well-funded, specialized emergency services unit, separate from immigration enforcement and attuned to the Borderlands’ specific environmental and demographic needs. But any lasting solution must reckon with the humanitarian crisis’ root cause — and that means de-militarizing the border and making it safer for migrants to access ports of entry.

“To actually end the death and suffering on the border,” Deighan said, “we need to end ‘prevention through deterrence’ and border enforcement policies that are intentionally leading people into danger.”